This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 187.15.25.116 (talk) at 05:53, 13 November 2010 (Undid revision 395744419 by Alefbe (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:53, 13 November 2010 by 187.15.25.116 (talk) (Undid revision 395744419 by Alefbe (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (July 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

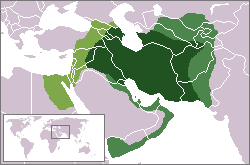

History of Iran has been intertwined with the history of a larger historical region, Greater Iran, which consists of the area from the Euphrates in the west to the Indus River and Jaxartes in the east and from the Caucasus, Caspian Sea, and Aral Sea in the north to the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman in the south.

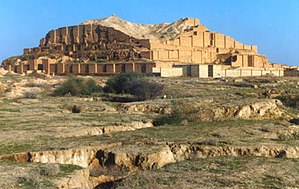

The southwestern part of the Iranian plateau participated in the wider Ancient Near East with Elam, from the Early Bronze Age. The Persian Empire proper begins in the Iron Age, following the influx of Iranian peoples which gave rise to the Median, Achaemenid, the Parthians, the Sassanid dynasties during classical antiquity.

Once a major empire of superpower proportions, Persia as it had long been called, has been overrun frequently and has had its territory altered throughout the centuries. Invaded and occupied by Greeks, Arabs, Turks, Mongols, and others—and often caught up in the affairs of larger powers—Persia has always reasserted its national identity and has developed as a distinct political and cultural entity.

Iran is home to one of the world's oldest continuous major civilizations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to 4000 BC. The Medes unified Iran as a nation and empire in 625 BC. The Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC) was the first of the Iranian empires to rule in Middle east and central Asia. They were succeeded by the Seleucid Empire, Parthians and Sassanids which governed Iran for almost 1,000 years.

The Islamic conquest of Persia (633–656) and the end of the Sassanid Empire was a turning point in Iranian history. Islamicization in Iran took place during 8th to 10th century and led to the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. However, the achievements of the previous Persian civilizations were not lost, but were to a great extent absorbed by the new Islamic polity and civilization.

After centuries of foreign occupation and short-lived native dynasties, Iran was once again reunified as an independent state in 1501 by the Safavid dynasty who established Shi'a Islam as the official religion of their empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam. Iran had been a monarchy ruled by a shah, or emperor, almost without interruption from 1501 until the 1979 Iranian revolution, when Iran officially became an Islamic Republic on 1 April 1979.

Prehistory

Further information: Archaeological sites in Iran Further information: Tappeh Sialk, Jiroft culture, and Shahr-i SokhtaPaleolithic

The earliest archaeological artifacts in Iran were found in the Kashafrud and Ganj Par sites that date back to Lower Paleolithic. Mousterian Stone tools made by Neanderthal man have also been found. There are also 9,000 year old human and animal figurines from Teppe Sarab in Kermanshah Province among the many other ancient artifacts. There are more cultural remains of Neanderthal man dating back to the Middle Paleolithic period, which mainly have been found in the Zagros region and fewer in central Iran at sites such as Shanidar, Kobeh, Kunji, Bisetun, Tamtama, Warwasi, Palegawra, and Yafteh Cave. Evidence for Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic periods are known mainly from the Zagros region in the caves of Kermanshah and Khoramabad.

Neolithic to Chalcolithic

]]

In the eighth millennium BC, agricultural communities such as Chogha Bonut (the earliest village in Susiana) started to form in western Iran, either as a result of indigenous development or of outside influences. Around about the same time the earliest known clay vessels and modeled human and animal terracotta figurines were produced at Ganj Dareh, also in western Iran. The south-western part of Iran was part of the Fertile Crescent where most of humanity's first major crops were grown, in villages such as Susa (now a city still existing since 7000 BC) and settlements such as Chogha Mish, dating back to 6800 BC.; there are 7,000 year old jars of wine excavated in the Zagros Mountains (now on display at The University of Pennsylvania) and ruins of 7,000 year old settlements such as Sialk are further testament to that. The two main Neolithic Iranian settlements were the Zayandeh Rud River Civilization and Ganj Dareh.

Bronze Age

Dozens of pre-historic sites across the Iranian plateau point to the existence of ancient cultures and urban settlements in the fourth millennium BC, One of the earliest civilizations in Iranian plateau was the Jiroft Civilization in southeastern Iran, in the province of Kerman. It is one of the most artifact-rich archaeological sites in the Middle East. Archaeological excavations in Jiroft led to the discovery of several objects belonging to the fourth millennium BC, a time that goes beyond the age of civilization in Mesopotamia. There is a large quantity of objects decorated with highly distinctive engravings of animals, mythological figures, and architectural motifs. The objects and their iconography are unlike anything ever seen before by archeologists. Many are made from chlorite, a gray-green soft stone; others are in copper, bronze, terracotta, and even lapis lazuli. Recent excavations at the sites have produced the world's earliest inscription which pre-dates Mesopotamian inscriptions.

There are records of numerous ancient civilizations on the Iranian plateau before the arrival of Iranian tribes from Central Asia during the Early Iron Age. One of the main civilizations of Iran was the Elam to the east of Mesopotamia, which started from around 3000 BC. The Jiroft culture occupied southeastern Iran and may have existed as far back as 3000 BC The Early Bronze Age saw the rise of urbanization into organized city states and the invention of writing (the Uruk period) in the Near East. While Bronze Age Elam made use of writing from an early time, the Proto-Elamite script remains undeciphered, and records from Sumer pertaining to Elam are scarce.

Further information: Tappeh Sialk, Jiroft civilization, Elam, and Mannaeans

Early Iron Age

Records become more tangible with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its records of incursions from the Iranian plateau. As early as the 10th and 9th century BC early Iranian peoples speaking arrived on the Iranian plateau from Central Asia (Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex) and/or via the Caucasus. The arrival of Iranians on the Iranian plateau forced the Elamites to relinquish one area of their empire after another and to take refuge in Susiana, Khuzistan and nearby area, which only then became coterminous with Elam. By the mid 1st millennium BC, Medes, Persians, Bactrians and Parthians populated the Iranian plateau.

Antiquity

Median and Achaemenid Empire (650 BC–330 BC)

Main articles: Median Empire and Achaemenid Empire |

|

|

|

In 646 BC The Assyrian king Ashurbanipal sacked Susa, which ended Elamite supremacy in the region. For over 150 years Assyrian kings of nearby Northern Mesopotamia were seeking to conquer Median tribes of Western Iran. Under pressure from the Assyrian empire, the small kingdoms of the western Iranian plateau coalesced into increasingly larger and more centralized states. In the second half of the 7th century BC, the Median tribes gained their independence and were united by Deioces. In 612 BC Cyaxares, Deioces' grandson, and the Babylonian king Nabopolassar invaded Assyria and laid siege to and eventually destroyed Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, which led to the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The Medes are credited with the foundation of Iran as a nation and empire, and established the first Iranian empire, the largest of its day until Cyrus the Great established a unified empire of the Medes and Persians leading to the Achaemenian Empire (648–330 BC).

Cyrus overthrew, in turn, the Medes, Lydians, and Babylonians, creating an empire far larger than Assyria. He was better able, through more benign policies, to reconcile his subjects to Persian rule; and the longevity of his empire was one result. The Persian king, like the Assyrian, was also "king of kings," xšāyaθiya xšāyaθiyānām (shāhanshāh in modern Persian) -- "great king," Megas Basileus, as known by the Greeks.

Cambyses rounds out the Empire by conquering the Egypt, overthrowing the Dynasty XXVI. Since he became ill and died before, or while, leaving Egypt, stories developed, as related by Herodotus, that he was struck down for impiety against the Egyptian pantheon. Be that as it may, it led to a bit of a succession crisis. The winner, Darius, based his claim on membership in a collateral line of the Achaemenid Dynasty.

In 499 BC Athens lent support to a revolt in Miletus which resulted in the sacking of Sardis. This led to an Achaemenid campaign against Greece known as the Greco-Persian Wars which lasted the first half of the 5th century BC. During the Greco-Persian wars Persia made some major advantages and razed Athens in 480 BC, but after a string of Greek victories the Persians were forced to withdraw while losing control of Macedonia, Thrace and Ionia. Fighting ended with the peace of Callias in 449 BC. In 404 BC following the death of Darius II Egypt rebelled under Amyrtaeus. Later Egyptian Pharaohs successfully resisted Persian attempts to reconquer Egypt until 343 BC when Egypt was reconquered by Artaxerxes III.

The Hellenic conquest and the Seleucid Empire (312 BCE – 63 BCE)

Main article: Seleucid Empire

In 334 BC-331 BC Alexander the Great, also known in the Zoroastrian Arda Wiraz Nâmag as "the accursed Alexander", defeated Darius III in the battles of Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela, swiftly conquering the Persian Empire by 331 BC. Alexander's empire broke up shortly after his death, and Alexander's general, Seleucus I Nicator, tried to take control of Persia, Mesopotamia, and later Syria and Asia Minor. His ruling family is known as the Seleucid Dynasty. However he was killed in 281 BC by Ptolemy Keraunos. Greek language, philosophy, and art came with the colonists. During the Seleucid Dynasty throughout Alexander's former empire, Greek became the common tongue of diplomacy and literature. Overland trade brought about some fascinating cultural exchanges. Buddhism came in from India, while Zoroastrianism travelled west to influence Judaism. Incredible statues of the Buddha in classical Greek styles have been found in Persia and Afghanistan, illustrating the mix of cultures that occurred around this time (See Greco-Buddhism).

Parthian Empire (248 BC – 224 AD)

Main article: Parthian Empire

Parthia was led by the Arsacid dynasty, who reunited and ruled over the Iranian plateau, after defeating the Greek Seleucid Empire, beginning in the late 3rd century BC, and intermittently controlled Mesopotamia between ca 150 BC and 224 AD. It was the second native dynasty of ancient Iran (Persia). Parthia was the Eastern arch-enemy of the Roman Empire; and it limited Rome's expansion beyond Cappadocia (central Anatolia). The Parthian armies included two types of cavalry: the heavily armed and armoured cataphracts and lightly armed but highly mobile mounted archers. For the Romans, who relied on heavy infantry, the Parthians were too hard to defeat, as both types of cavalry were much faster and more mobile than foot soldiers. On the other hand, the Parthians found it difficult to occupy conquered areas as they were unskilled in siege warfare. Because of these weaknesses, neither the Romans nor the Parthians were able to completely annex each other.

The Parthian empire lasted five centuries, longer than most Eastern Empires. The end of this long lasted empire came in 224 AD, when the empire was loosely organized and the last king was defeated by one of the empire's vassals, the Persians of the Sassanian dynasty.

Sassanid Empire (224 – 651 AD)

Main article: Sassanid EmpireThe first Shah of the Sassanid Empire, Ardashir I, started reforming the country both economically and militarily. The empire's territory encompassed all of today's Iran, Iraq, Armenia, Afghanistan, eastern parts of Turkey, and parts of Syria, Pakistan, Caucasia, Central Asia, India and Arabia. During Khosrau II's rule in 590-628, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine and Lebanon were also annexed to the Empire. The Sassanians called their empire Erânshahr (or Iranshahr, "Dominion of the Aryans", i.e. of Iranians).

A chapter of Iran's history followed after roughly six hundred years of conflict with the Roman Empire. During this time, the Sassanian and Romano-Byzantine armies clashed for influence in Mesopotamia, Armenia and the Levant. Under Justinian I, the war came to an uneasy peace with payment of tribute to the Sassanians. However the Sassanians used the deposition of the Byzantine Emperor Maurice as a casus belli to attack the Empire. After many gains, the Sassanians were defeated at Issus, Constantinople and finally Nineveh, resulting in peace. With the conclusion of the Roman-Persian wars, the war-exhausted Persians lost the Battle of al-Qâdisiyah (632) in Hilla, (present day Iraq) to the invading forces of Islam.

The Sassanian era, encompassing the length of the Late Antiquity period, is considered to be one of the most important and influential historical periods in Iran, and had a major impact on the world. In many ways the Sassanian period witnessed the highest achievement of Persian civilization, and constitutes the last great Iranian Empire before the adoption of Islam. Persia influenced Roman civilization considerably during Sassanian times, their cultural influence extending far beyond the empire's territorial borders, reaching as far as Western Europe, Africa, China and India and also playing a prominent role in the formation of both European and Asiatic medieval art. This influence carried forward to the Islamic world. The dynasty's unique and aristocratic culture transformed the Islamic conquest and destruction of Iran into a Persian Renaissance. Much of what later became known as Islamic culture, architecture, writing and other contributions to civilization, were taken from the Sassanian Persians into the broader Muslim world.

Medieval Iran

Caliphate and Sultanate era

Main articles: Caliphate and SultanateIslamic Conquest

Main article: Islamic conquest of Iran

Muslims invaded Iran in the time of Umar (637) and conquered it after several great battles. Yazdegerd III fled from one district to another until a local miller killed him for his purse at Merv in 651. By 674, Muslims had conquered Greater Khorasan (which included modern Iranian Khorasan province and modern Afghanistan, Transoxania, and Pakistan). The Islamic conquest of Persia led to the end of the Sassanid Empire and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. The majority of Iranians gradually converted to Islam. However, most of the achievements of the previous Persian civilizations were not lost, but were absorbed by the new Islamic polity.

As Bernard Lewis has quoted

"These events have been variously seen in Iran: by some as a blessing, the advent of the true faith, the end of the age of ignorance and heathenism; by others as a humiliating national defeat, the conquest and subjugation of the country by foreign invaders. Both perceptions are of course valid, depending on one's angle of vision."

Umayyad Caliphate

Main article: UmayyadsAfter the fall of Sasanian dynasty in 651, the Umayyad Arabs adopted many Persian customs especially the administrative and the court mannerisms. Arab provincial governors were undoubtedly either Persianized Arameans or ethnic Persians; certainly Persian remained the language of official business of the caliphate until the adoption of Arabic toward the end of the 7th century, when in 692 minting began at the caliphal capital, Damascus. The new Islamic coins evolved from imitations of Sassanian coins (as well as Byzantine), and the Pahlavi script on the coinage was replaced with Arabic alphabet.

During the reign of the Ummayad dynasty, the Arab conquerors imposed Arabic as the primary language of the subject peoples throughout their empire. Hajjāj ibn Yusuf, who was not happy with the prevalence of the Persian language in the divan, ordered the official language of the conquered lands to be replaced by Arabic, sometimes by force. In Biruni's From The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries for example it is written:

"When Qutaibah bin Muslim under the command of Al-Hajjaj bin Yousef was sent to Khwarazmia with a military expedition and conquered it for the second time, he swiftly killed whomwever wrote the Khwarazmian native language that knew of the Khwarazmian heritage, history, and culture. He then killed all their Zoroastrian priests and burned and wasted their books, until gradually the illiterate only remained, who knew nothing of writing, and hence their history was mostly forgotten."

There are a number of historians who see the rule of the Umayyads as setting up the "dhimmah" to increase taxes from the dhimmis to benefit the Arab Muslim community financially and by discouraging conversion. Governors lodged complaints with the caliph when he enacted laws that made conversion easier, depriving the provinces of revenues.

In the 7th century AD, when many non-Arabs such as Persians entered Islam were recognized as Mawali and treated as second class citizens by the ruling Arab elite, until the end of the Umayyad dynasty. During this era Islam was initially associated with the ethnic identity of the Arab and required formal association with an Arab tribe and the adoption of the client status of mawali. The half-hearted policies of the late Umayyads to tolerate non-Arab Muslims and Shi'as had failed to quell unrest among these minorities. With the death of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 743, the Islamic world was launched into civil war. Abu Muslim was sent to Khorasan by the Abbasids initially as a propagandist and then to revolt on their behalf. He took Merv defeating the Umayyad governor there Nasr ibn Sayyar. He became the de facto Abbasid governor of Khurasan. In 750, Abu Muslim became leader of the Abbasid army and defeated the Umayyads at the Battle of the Zab. Abu Muslim stormed Damascus, the capital of the Umayyad caliphate, later that year.

Abbasid Caliphate and Iranian semi-independent governments

Main articles: Abbasids, Tahirids, Saffarids, Ziyarids, Samanids, and Buyids

The Abbasid army consisted primarily of Khorasanians and was led by an Iranian general, Abu Muslim Khorasani. It contained both Iranian and Arab elements, and the Abbasids enjoyed both Iranian and Arab support. The Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750.

One of the first changes the Abbasids made after taking power from the Umayyads was to move the empire's capital from Damascus, in Levant, to Iraq. The latter region was influenced by Persian history and culture, and moving the capital was part of the Persian mawali demand for Arab influence in the empire. The city of Baghdad was constructed on the Tigris River, in 762, to serve as the new Abbasid capital. The Abbasids established the position of vizier like Barmakids in their administration, which was the equivalent of a "vice-caliph", or second-in-command. Eventually, this change meant that many caliphs under the Abbasids ended up in a much more ceremonial role than ever before, with the vizier in real power. A new Persian bureaucracy began to replace the old Arab aristocracy, and the entire administration reflected these changes, demonstrating that the new dynasty was different in many ways to the Umayyads.

By the 9th century, Abbasid control began to wane as regional leaders sprang up in the far corners of the empire to challenge the central authority of the Abbasid caliphate. The Abbasid caliphs began enlisting Turkic-speaking warriors who had been moving out of Central Asia into Transoxiana as slave warriors as early as the ninth century. Shortly thereafter the real power of the Abbasid caliphs began to wane; eventually they became religious figureheads while the warrior slaves ruled. As the power of the Abbasid caliphs diminished, a series of dynasties rose in various parts of Iran, some with considerable influence and power. Among the most important of these overlapping dynasties were the Tahirids in Khorasan (820-72); the Saffarids in Sistan (867-903); and the Samanids (875-1005), originally at Bokhara. The Samanids eventually ruled an area from central Iran to Pakistan. By the early 10th century, the Abbasids almost lost control to the growing Persian faction known as the Buwayhid dynasty(934-1055). Since much of the Abbasid administration had been Persian anyway, the Buwayhid were quietly able to assume real power in Baghdad. The Buwayhid were defeated in the mid-11th century by the Seljuk Turks, who continued to exert influence over the Abbasids, while publicly pledging allegiance to them. The balance of power in Baghdad remained as such - with the Abbasids in power in name only - until the Mongol invasion of 1258 sacked the city and definitively ended the Abbasid dynasty.

During the Abbassid period an enfranchisement was experienced by the mawali and a shift was made in political conception from that of a primarily Arab empire to one of a Muslim empire and c. 930 a requirement was enacted that required all bureaucrats of the empire be Muslim.

Islamic golden age, Shu'ubiyya movement and Persianization process

See also: Islamization in Iran, Islamic Golden Age, and Shu'ubiyyaIslamization was a long process by which Islam was gradually adopted by the majority population of Iran.

Richard Bulliet's "conversion curve" indicates that only about 10% of Iran converted to Islam during the relatively Arab-centric Umayyad period. Beginning in the Abassid period, with its mix of Persian as well as Arab rulers, the Muslim percentage of the population rose. As Persian Muslims consolidated their rule of the country, the Muslim population rose from approx. 40% in the mid 9th century to close to 100% by the end of 11th century. Seyyed Hossein Nasr suggests that the rapid increase in conversion was aided by the Persian nationality of the rulers.

Although Persians adopted the religion of their conquerors, over the centuries they worked to protect and revive their distinctive language and culture, a process known as Persianization. Arabs and Turks participated in this attempt.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, non-Arab subjects of the Ummah created a movement called Shu'ubiyyah in response to the privileged status of Arabs. Most of those behind the movement were Persian, but references to Egyptians, Berbers and Aramaeans are attested. Citing as its basis Islamic notions of equality of races and nations, the movement was primarily concerned with preserving Persian culture and protecting Persian identity, though within a Muslim context. The most notable effect of the movement was the survival of the Persian language to the present day.

The Samanid dynasty led the revival of Persian culture and the first important Persian poet after the arrival of Islam, Rudaki, was born during this era and was praised by Samanid kings. The Samanids also revived many ancient Persian festivals. Their successor, the Ghaznawids, who were of non-Iranian Turkic origin, also became instrumental in the revival of Persian.

The culmination of the Persianization movement was the Shahname, the national epic of Iran, written almost entirely in Persian. This voluminous work, reflects Iran's ancient history, its unique cultural values, its pre-islamic Zoroastrian religion, and its sense of nationhood.

According to Bernard Lewis:

"Iran was indeed Islamized, but it was not Arabized. Persians remained Persians. And after an interval of silence, Iran reemerged as a separate, different and distinctive element within Islam, eventually adding a new element even to Islam itself. Culturally, politically, and most remarkable of all even religiously, the Iranian contribution to this new Islamic civilization is of immense importance. The work of Iranians can be seen in every field of cultural endeavor, including Arabic poetry, to which poets of Iranian origin composing their poems in Arabic made a very significant contribution. In a sense, Iranian Islam is a second advent of Islam itself, a new Islam sometimes referred to as Islam-i Ajam. It was this Persian Islam, rather than the original Arab Islam, that was brought to new areas and new peoples: to the Turks, first in Central Asia and then in the Middle East in the country which came to be called Turkey, and of course to India. The Ottoman Turks brought a form of Iranian civilization to the walls of Vienna..."

The Islamization of Iran was to yield deep transformations within the cultural, scientific, and political structure of Iran's society: The blossoming of Persian literature, philosophy, medicine and art became major elements of the newly forming Muslim civilization. Inheriting a heritage of thousands of years of civilization, and being at the "crossroads of the major cultural highways", contributed to Persia emerging as what culminated into the "Islamic Golden Age". During this period, hundreds of scholars and scientists vastly contributed to technology, science and medicine, later influencing the rise of European science during the Renaissance.

The most important scholars of almost all of the Islamic sects and schools of thought were Persian or live in Iran including most notable and reliable Hadith collectors of Shia and Sunni like Shaikh Saduq, Shaikh Kulainy, Imam Bukhari, Imam Muslim and Hakim al-Nishaburi, the greatest theologians of Shia and Sunni like Shaykh Tusi, Imam Ghazali, Imam Fakhr al-Razi and Al-Zamakhshari, the greatest physicians, astronomers, logicians, mathematicians, metaphysicians, philosophers and scientists like Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, the greatest Shaykh of Sufism like Rumi, Abdul-Qadir Gilani.

Turco-Persian dynasties

In 962 a Turkish governor of the Samanids, Alptigin, conquered Ghazna (in present-day Afghanistan) and established a dynasty, the Ghaznavids, that lasted to 1186. The Ghaznavid empire grew by taking all of the Samanid territories south of the Amu Darya in the last decade of the 10th century, and eventually occupied much of present-day Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and northwest India. The Ghaznavids are generally credited with launching Islam into Hindu-dominated India. The invasion of India was undertaken in 1000 by the Ghaznavid ruler, Mahmud, and continued for several years. They were unable to hold power for long, however, particularly after the death of Mahmud in 1030. By 1040 the Seljuks had taken over the Ghaznavid lands in Iran.

The Seljuks, who like the Ghaznavids were Turks, slowly conquered Iran over the course of the 11th century. The dynasty had its origins in the Turcoman tribal confederations of Central Asia and marked the beginning of Turkic power in the Middle East. They established a Sunni Muslim dynasty that ruled parts of Central Asia and the Middle East from the 11th to 14th centuries. They set up an empire known as Great Seljuk Empire that stretched from Anatolia to Pakistan and was the target of the First Crusade. Today they are regarded as the cultural ancestors of the Western Turks, the present-day inhabitants of Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Turkmenistan, and they are remembered as great patrons of Persian culture, art, literature, and language. Their leader, Tughril Beg, turned his warriors against the Ghaznavids in Khorasan. He moved south and then west, conquering but not wasting the cities in his path. In 1055 the caliph in Baghdad gave Tughril Beg robes, gifts, and the title King of the East. Under Tughril Beg's successor, Malik Shah (1072–1092), Iran enjoyed a cultural and scientific renaissance, largely attributed to his brilliant Iranian vizier, Nizam al Mulk. These leaders established the observatory where Omar Khayyám did much of his experimentation for a new calendar, and they built religious schools in all the major towns. They brought Abu Hamid Ghazali, one of the greatest Islamic theologians, and other eminent scholars to the Seljuk capital at Baghdad and encouraged and supported their work.

When Malik Shah I died in 1092, the empire split as his brother and four sons quarrelled over the apportioning of the empire among themselves. In Anatolia, Malik Shah I was succeeded by Kilij Arslan I who founded the Sultanate of Rûm and in Syria by his brother Tutush I. In Persia he was succeeded by his son Mahmud I whose reign was contested by his other three brothers Barkiyaruq in Iraq, Muhammad I in Baghdad and Ahmad Sanjar in Khorasan. As Seljuk power in Iran weakened, other dynasties began to step up in its place, including a resurgent Abbasid caliphate and the Khwarezmshahs. The Khwarezmid Empire was a Sunni Muslim dynasty that ruled in Central Asia. Originally vassals of the Seljuks, they took advantage of the decline of the Seljuks to expand into Iran. In 1194 the Khwarezmshah Ala ad-Din Tekish defeated the Seljuk sultan Tugrul III in battle and the Seljuk empire in Iran collapsed. Of the former Seljuk Empire, only the Sultanate of Rüm in Anatolia remained.

A serious internal threat to the Seljuks during their reign came from the Ismailis, a secret sect with headquarters at Alamut between Rasht and Tehran. They controlled the immediate area for more than 150 years and sporadically sent out adherents to strengthen their rule by murdering important officials. Several of the various theories on the etymology of the word assassin derive from these killers.

Mongols, Timurids and local governments

Main articles: Mongol invasion of Central Asia, Mongol Empire, Ilkhanate, and Timurid dynasty

The Khwarezmid Empire only lasted for a few decades, until the arrival of the Mongols. Genghis Khan had unified the Mongols, and under him the Mongol Empire quickly expanded in several directions, until by 1218 it bordered Khwarezm. At that time, the Khwarezmid Empire was ruled by Ala ad-Din Muhammad (1200–1220). Muhammad, like Genghis, was intent on expanding his lands and had gained the submission of most of Iran. He declared himself shah and demanded formal recognition from the Abbasid caliph an-Nasir. When the caliph rejected his claim, Ala ad-Din Muhammad proclaimed one of his nobles caliph and unnsuccessfully tried to depose an-Naisr.

The Mongol invasion of Iran began in 1219, after two diplomatic missions to Khwarezm sent by Genghis Khan had been massacred. During 1220–21 Bukhara, Samarkand, Herat, Tus, and Neyshabur were razed, and the whole populations were slaughtered. The Khwarezm-Shah fled, to die on an island off the Caspian coast. Before his death in 1227, Genghis had reached western Azarbaijan, pillaging and burning cities along the way.

The Mongol invasion was disastrous to the Iranians. Although the Mongol invaders were eventually converted to Islam and accepted the culture of Iran, the Mongol destruction of the Islamic heartland marked a major change of direction for the region. Much of the six centuries of Islamic scholarship, culture, and infrastructure was destroyed as the invaders burned libraries, and replaced mosques with Buddhist temples. The Mongols killed many civilians. Just in Merv and Urgench(Gorganj) about 2.5 million civilians were slaughtered. Destruction of qanat irrigation systems destroyed the pattern of relatively continuous settlement, producing numerous isolated oasis cities in a land where they had previously been rare. A large number of people, particularly males, were killed; between 1220 and 1258, the total population of Iran may have dropped from 2,500,000 to 250,000 as a result of mass extermination and famine.

After Genghis' death, Iran was ruled by several Mongol commanders. Genghis' grandson, Hulagu Khan, was tasked with expanding the Mongol empire in Iran in 1255. Arriving with an army, he established himself in the region and founded the Ilkhanate, which would rule Iran for the next eighty years. He seized Baghdad in 1258 and put the last Abbasid caliph to death. The westward advance of his forces was stopped by the Mamelukes, however, at the Battle of Ain Jalut in Palestine in 1260. Hulagu's campaigns against the Muslims also enraged Berke, khan of the Golden Horde and a convert to Islam. Hulagu and Berke fought against each other, demonstrating the weakening unity of the Mongol empire.

The rule of Hulagu's great-grandson, Ghazan Khan (1295–1304) saw the establishment of Islam as the state religion of the Ilkhanate. Ghazan and his famous Iranian vizier, Rashid al-Din, brought Iran a partial and brief economic revival. The Mongols lowered taxes for artisans, encouraged agriculture, rebuilt and extended irrigation works, and improved the safety of the trade routes. As a result, commerce increased dramatically. Items from India, China, and Iran passed easily across the Asian steppes, and these contacts culturally enriched Iran. For example, Iranians developed a new style of painting based on a unique fusion of solid, two-dimensional Mesopotamian painting with the feathery, light brush strokes and other motifs characteristic of China. After Ghazan's nephew Abu Said died in 1335, however, the Ilkhanate lapsed into civil war and was divided between several petty dynasties - most prominently the Jalayirids, Muzaffarids, Sarbadars and Kartids.

Iran remained divided until the arrival of Timur, who is variously described as of Mongol or Turkic origin. After establishing a power base in Transoxiana, he invaded Iran in 1381 and conquered it piece by piece. Timur's campaigns were known for their brutality; many people were slaughtered and several cities were destroyed. His regime was characterized by its inclusion of Iranians in administrative roles and its promotion of architecture and poetry. His successors, the Timurids, maintained a hold on most of Iran until 1452, when they lost the bulk of it to Black Sheep Turkmen. The Black Sheep Turkmen were conquered by the White Sheep Turkmen under Uzun Hasan in 1468; Uzun Hasan and his successors were the masters of Iran until the rise of the Safavids.

Sunnism and Shiism in pre-Safavid Iran

Main article: Islam in Iran

Sunnism was dominant form of Islam in most part of Iran from the beginning until rise of Safavids empire. Sunni Islam was more than 90% of population of Persia before Safavids. According to Mortaza Motahhari the majority of Iranian scholars and masses remained Sunni till the time of the Safavids. The domination of Sunnis did not mean Shia were rootless in Iran. The writers of The Four Books of Shia were Iranian as well as many other great Shia scholars.

The domination of the Sunni creed during the first nine Islamic centuries characterizes the religious history of Iran during this period. There were however some exceptions to this general domination which emerged in the form of the Zaydīs of Tabaristan, the Buwayhid, the rule of Sultan Muhammad Khudabandah (r. Shawwal 703-Shawwal 716/1304-1316) and the Sarbedaran. Apart from this domination there existed, firstly, throughout these nine centuries, Shia inclinations among many Sunnis of this land and, secondly, original Imami Shiism as well as Zaydī Shiism had prevalence in some parts of Iran. During this period, Shia in Iran were nourished from Kufah, Baghdad and later from Najaf and Hillah. Shiism were dominant sect in Tabaristan, Qom, Kashan, Avaj and Sabzevar. In many other areas merged population of Shia and Sunni lived.

During the 10th and 11th centuries, Fatimids sent Ismailis Da'i (missioners) to Iran as well as other Muslim lands. When Ismailis divided into two sects, Nizaris established their base in Iran. Hassan-i Sabbah conquered fortresses and captured Alamut in 1090 AD. Nizaris used this fortress until a Mongol raid in 1256 AD.

After the Mongol raid and fall of the Abbasids Sunni hierarchies suffered a lot. Not only did they loose the caliphate but also Sunni was not official madhab for a while. On the other hand Shia whose center wasn't in Iran at that time didn't suffered and for the first time it could invite other Muslims openly. Even several local Shia dynasties like Sarbadars were established during this time.

The main change occurred in the beginning of the 16th century, when Ismail I founded the Safavid dynastyand initiated a religious policy to recognize Shi'a Islam as the official religion of the Safavid Empire, and the fact that modern Iran remains an officially Shi'ite state is a direct result of Ismail's actions.

The Shâhs of Iran, 1501-1979 AD

The Safavids, 1501-1736

Main article: Safavid dynasty

The Safavids were actually of Turkomen origin and established themselves first at Tabriz, which had been the capital of the Ilkhanate, in Turkish speaking Azerbaijan. At first religion was much more important than any ethnic identity, and Ismail I created a powerful Shi'ite identity for his dynasty and state. This became a unifying and militant force in Iran, especial vis à vis Orthodox Turkey, right down to the present. Abbas I, however, moved the capital to Isfahan, and the state began to take on more of a Persian than a Turkic character. In retrospect, what the Safavids did was to succeed in establishing a new Persian national monarchy.

Nader Shah and his successors

Main articles: Afsharid dynasty and Zand dynasty

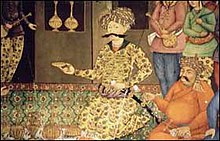

Iran's territorial integrity was restored by an Afshar warlord from Khorasan, Nader Shah. He defeated the Afghans and Ottomans, reinstalled the Safavids on the throne and negotiated Russian withdrawal. By 1736, Nader had become so powerful he was able to depose the Safavids and have himself crowned shah. Nader was one of the last great conquerors of Asia and his military reforms enabled his army to take Kandahar and invade Mughal India, sacking Delhi in 1739. But the increasing cruelty and oppressiveness of his later years provoked multiple revolts and, ultimately, Nader's assassination in 1747.

Nader's death was followed by a period of anarchy in Iran as rival army commanders fought for power. Nader's own family, the Afsharids, were soon reduced to holding on to a small domain in Khorasan. Ahmad Shah Durrani founded an independent state which became modern Afghanistan. From his capital Shiraz, Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty ruled "an island of relative calm and peace in an otherwise bloody and destructive period." His death in 1779 led to yet another civil war in which the Qajar dynasty eventually triumphed and became shahs of Iran.

Qajar dynasty (1796–1925)

Main articles: Qajar dynasty and Anglo-Persian War

By the 17th century, European countries, including Great Britain, Imperial Russia, and France, had already started establishing colonial footholds in the region. Iran as a result lost sovereignty over many of its provinces to these countries via the Treaty of Turkmenchay, the Treaty of Gulistan, and others.

A new era in the History of Persia dawned with the Constitutional Revolution of Iran against the Shah in the late 19th and early 20th century. The Shah managed to remain in power, granting a limited constitution in 1906 (making the country a constitutional monarchy). The first Majlis (parliament) was convened on October 7, 1906.

The discovery of oil in 1908 by the British in Khuzestan spawned intense renewed interest in Persia by the British Empire (see William Knox D'Arcy and Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now BP). Control of Persia remained contested between the United Kingdom and Russia, in what became known as The Great Game, and codified in the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which divided Persia into spheres of influence, regardless of her national sovereignty.

During World War I, the country was occupied by British and Russian forces but was essentially neutral (see Persian Campaign). In 1919, after the Russian revolution and their withdrawal, Britain attempted to establish a protectorate in Iran, which was unsuccessful.

Finally, the Constitutionalist movement of Gilan and the central power vacuum caused by the instability of the Qajar government resulted in the rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi and the establishing Pahlavi dynasty in 1925.

The Pahlavis, 1924-1979

Main article: Pahlavi dynastyThe Pahlavi dynasty begins as a military coup, a kind of Iranian Young Turks rebellion, but then quickly became more like a traditional change of dynasty. A story about Rezā Shāh is that he was informed one day about about a mullah who was preaching in favor of the Veil and, by implication, against the Shāh. Rezā immediately rode down to the mosque with some troops and personally nailed a veil to the forehead of the mullah. Although such an endorsement of Westernization was relatively mild compared to what Kemal Atatürk was doing in Turkey, it would ultimately prove too much for the country.

The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, and what may have been Rezā sympathy for Germany, led to the Russians and British occupying the country and deposing the Shāh. This opened a transport route to the Soviets and also secured Allied control of Iranian oil. A similar problem of getting caught in the middle of geopolitics occurred in 1953, after prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh tried nationalizing the Iranian oil industry. This was regarded not only as hostile, but as effectively pro-Soviet. In 1953, as in 1941, Rezā Shāh's son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was more amenable to Western interests. The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, with American support, took out Mossadegh. In the demonology of anti-imperialism, this is counted as one of the primal sins of American foreign policy. The Soviet occupation of Iran apparently doesn't rate the same indignation.

Iran was ruled as an autocracy under the shah with American support from that time until the revolution. The Iranian entered into agreement with an international consortium of foreign companies which ran the Iranian oil facilities for the next 25 years spitting profits fifty-fifty with Iran but not allowing Iran to audit their accounts or have members on their board of directors. In 1957 martial law was ended after 16 years and Iran became closer to the West, joining the Baghdad Pact and receiving military and economic aid from the US. In 1961, Iran initiated a series of economic, social, agrarian and administrative reforms to modernize the country that became known as the Shah's White Revolution.

The core of this program was land reform. Modernization and economic growth proceeded at an unprecedented rate, fueled by Iran's vast petroleum reserves, the third-largest in the world. However the reforms, including the White Revolution, did not greatly improve economic conditions and the liberal pro-Western policies alienated certain Islamic religious and political groups. In early June 1963 several days of massive rioting in support of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini following the clerics arrested for a speech attacking the shah.

Two year later, premier Hassan Ali Mansur was assassinated and the internal security service, SAVAK, became more violently active. In the 1970s leftist guerilla groups such as Mujaheddin-e-Khalq (MEK), emerged and attacked regime and foreign targets.

Nearly a hundred Iran political prisoners were killed by the SAVAK during the decade before the revolution and many more were arrested and tortured. The Islamic clergy, headed by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (who had been exiled in 1964), were becoming increasingly vociferous.

Iran greatly increased its defense budget and by the early 1970s was the region's strongest military power. International relations with its neighbor Iraq were not good, mainly due to a dispute over the Shatt al-Arab waterway. In November, 1971 Iranian forces seized control of three islands at the mouth of the Persian Gulf; in response Iraq expelled thousands of Iranian nationals. Following a number of clashes in April, 1969, Iran abrogated the 1937 accord and demanded a renegotiation.

In mid-1973, the Shah returned the oil industry to national control. Following the Arab-Israeli War of October 1973, Iran did not join the Arab oil embargo against the West and Israel. Instead it used the situation to raise oil prices, using the money gained for modernization and to increase defense spending.

A border dispute between Iraq and Iran was resolved with the signing of the Algiers Accord on March 6, 1975.

Iranian Revolution and the Islamic Republic

Main articles: Iranian Revolution and History of the Islamic Republic of Iran Further information: Iran hostage crisis, United States-Iran relations, Iran-Israel relations, and Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

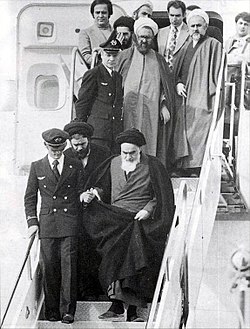

The Iranian Revolution, also known as the Islamic Revolution, was the revolution that transformed Iran from a monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, to an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution and founder of the Islamic Republic. Its time span can be said to have begun in January 1978 with the first major demonstrations, and concluded with the approval of the new theocratic Constitution — whereby Ayatollah Khomeini became Supreme Leader of the country — in December 1979. In between, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left the country for exile in January 1979 after strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country, and on February 1, 1979 Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran to a greeting of several million Iranians. The final collapse of the Pahlavi dynasty occurred shortly after on February 11 when Iran's military declared itself "neutral" after guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed troops loyal to the Shah in armed street fighting. Iran officially became an Islamic Republic on April 1, 1979 when Iranians overwhelmingly approved a national referendum to make it so.

The ideology of revolutionary government was populist, nationalist and most of all Shi'a Islamic. Its unique constitution is based on the concept of velayat-e faqih the idea advanced by Khomeini that Muslims —- in fact everyone —- requires "guardianship", in the form of rule or supervision by the leading Islamic jurist or jurists. Khomeini served as this ruling jurist, or supreme leader, until his death in 1989.

Iran's rapidly modernising, capitalist economy was replaced by populist and Islamic economic and cultural policies. Much industry was nationalized, laws and schools Islamicized, and Western influences banned.

The Islamic revolution also created great impact around the world. In the non-Muslim world it has changed the image of Islam, generating much interest in the politics and spirituality of Islam, along with "fear and distrust towards Islam" and particularly the Islamic Republic and its founder.

Khomeini era

Khomeini served as leader of the revolution or as Supreme Leader of Iran from 1979 to his death on June 3, 1989. This era was dominated by the consolidation of the revolution into a theocratic republic under Khomeini, and by the costly and bloody war with Iraq.

The consolidation lasted until 1982-3), as Iran coped with the damage to its economy, military, and apparatus of government, and protests and uprisings by secularists, leftists, and more traditional Muslims — formerly ally revolutionaries but now rivals — were effectively suppressed. In the summer of 1979 a new constitution giving Khomeini a powerful post as guardian jurist Supreme Leader and a clerical Council of Guardians power over legislation and elections, was drawn up by an Assembly of Experts for Constitution. The new constitution was approved by referendum in December 1979.

An early event in the history of the Islamic republic that had a long term impact was the Iran hostage crisis. Following the admitting of the former Shah of Iran into the United States for cancer treatment, on November 4, 1979, Iranian students seized US embassy personnel, labeling the embassy a "den of spies." Fifty-two hostages were held for 444 days until January 1981. The takeover was enormously popular in Iran, where thousands gathered in support of the hostage takers, and it is thought to have strengthened the prestige of the Ayatollah Khomeini and consolidated the hold of anti-Americanism. It was at this time that Khomeini began referring to America as the "Great Satan." In America, where it was considered a violation of the long-standing principle of international law that diplomats may be expelled but not held captive, it created a powerful anti-Iranian backlash. Relations between the two countries have remained deeply antagonistic and American international sanctions have hurt Iran's economy.

During the crisis, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein attempted to take advantage of the disorder of the Revolution, the weakness of the Iranian military and the revolution's antagonism with Western governments. The once-strong Iranian military had been disbanded during the revolution, and with the Shah ousted, Hussein had ambitions to position himself as the new strong man of the Middle East. He also sought to expand Iraq's access to the Persian Gulf by acquiring territories that Iraq had claimed earlier from Iran during the Shah's rule. Of chief importance to Iraq was Khuzestan which not only boasted a substantial Arab population, but rich oil fields as well. On the unilateral behalf of the United Arab Emirates, the islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs became objectives as well. With these ambitions in mind, Hussein planned a full-scale assault on Iran, boasting that his forces could reach the capital within three days. On September 22, 1980 the Iraqi army invaded Iran at Khuzestan, precipitating the Iran–Iraq War. The attack took revolutionary Iran completely by surprise.

Although Saddam Hussein's forces made several early advances, by 1982, Iranian forces had pushed the Iraqi army back into Iraq. Khomeini sought to export his Islamic revolution westward into Iraq, especially on the majority Shi'a Arabs living in the country. The war then continued for six more years until 1988, when Khomeini, in his words, "drank the cup of poison" and accepted a truce mediated by the United Nations.

Tens of thousands of Iranian civilians and military personnel were killed when Iraq used chemical weapons in its warfare. Iraq was financially backed by Egypt, the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf, the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact states, the United States (beginning in 1983), France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil, and the People's Republic of China (which also sold weapons to Iran).

There were more than 100,000 Iranian victims of Iraq's chemical weapons during the eight-year war. The total Iranian casualties of the war were estimated to be between 500,000 and 1,000,000. Almost all relevant international agencies have confirmed that Saddam engaged in chemical warfare to blunt Iranian human wave attacks; these agencies unanimously confirmed that Iran never used chemical weapons during the war.

Starting on 19 July 1988 and lasting about five months the government systematically executed thousands of political prisoners across Iran. This is commonly referred to as the 1988 executions of Iranian political prisoners or the 1988 Iranian Massacre. The main target was the membership of the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI), although a lesser number of political prisoners from other leftist groups were also included such as the Tudeh Party of Iran (Communist Party). Estimates of the number executed vary from 1,400 to 30,000.

Khamenei era

On his deathbed in 1989, Khomeini appointed a 25-man Constitutional Reform Council which named Ali Khamenei as the next Supreme Leader, and made a number of changes to Iran's constitution. A smooth transition followed Khomeini's death on June 3, 1989. While Khamenei lacked Khomeini's "charisma and clerical standing", he developed a network of supporters within Iran's armed forces and its economically powerful religious foundations. Under his reign Iran's regime is said - by at least one observer - to resemble more "a clerical oligarchy ... than an autocracy."

Succeeding Khamenei as president was pragmatic conservative Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who served two four-year terms and focused his efforts on rebuilding Iran's economy and war-damaged infrastructure though low oil prices hampered this endeavour. His regime also successfully promoted birth control, cut military spending and normalized relations with neighbors such as Saudi Arabia. During the Persian Gulf War in 1991 the country remained neutral, restricting its action to the condemnation of the U.S. and allowing fleeing Iraqi aircraft and refugees into the country.

Rafsanjani was succeeded in 1997 by the reformist Mohammad Khatami. His presidency was soon marked by tensions between the reform-minded government and an increasingly conservative and vocal clergy. This rift reached a climax in July 1999 when massive anti-government protests erupted in the streets of Tehran. The disturbances lasted over a week before police and pro-government vigilantes dispersed the crowds.

Khatami was re-elected in June 2001 but his efforts were repeatedly blocked by the religious Guardian Council. Conservative elements within Iran's government moved to undermine the reformist movement, banning liberal newspapers and disqualifying candidates for parliamentary elections. This clampdown on dissent, combined with the failure of Khatami to reform the government, led to growing political apathy among Iran's youth.

In June 2003, anti-government protests by several thousand students took place in Tehran. Several human rights protests also occurred in 2006.

In Iranian presidential election, 2005 Mahmoud Ahmadinejad,the mayor of Tehran, became the sixth president of Iran, after winning 62 percent of the vote in the run-off poll, against former president Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. During the authorization ceremony he kissed Khamenei's hand in demonstration of his loyalty to him.

During this time, the American invasion of Iraq, overthrow of Sadam Hussein's regime and empowerment of its Shi'a majority, all strengthened Iran's position in the region particularly in the mainly Shia south of Iraq, where a top Shia leader in the week of September 3, 2006 renewed demands for an autonomous Shia region. At least one commentator (Former U.S. Defense Secretary William S. Cohen) has stated that as of 2009 Iran's growing power has eclipsed anti-Zionism as the major foreign policy issue in the middle east.

During 2005 and 2006, there were claims that the United States and Israel were planning to attack Iran, for many different claimed reasons, including Iran's civilian nuclear energy program which the United States and some other states fear could lead to a nuclear weapons program, crude oil and other strategic reasons (including the Iranian Oil Bourse), electoral reasons in the USA and in Iran. P.R. China and Russia oppose military action of any sort and oppose economic sanctions. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei issued a fatwa forbidding the production, stockpiling and use of nuclear weapons. The fatwa was cited in an official statement by the Iranian government at an August 2005 meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna.

In 2009 Ahmadinejad's reelection was hotly disputed and marred by large protests that formed the "greatest domestic challenge" to the leadership of the Islamic Republic "in 30 years". Reformist opponent Mir-Hossein Mousavi and his supporters alleged voting irregularities and by 1 July 2009, 1000 people had been arrested and 20 killed in street demonstrations. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and other Islamic officials blamed foreign powers for fomenting the protest.

|

See also

Notes

- http://anthropology.net/user/kambiz_kamrani/blog/2006/12/05/engineering_an_empire_the_persians

- Persia and the Greeks. Persian Fire: The First World Empire

- ^ Xinhua, "New evidence: modern civilization began in Iran", 10 Aug 2007, retrieved 1 October 2007

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9371723 Encyclopædia Britannica Concise Encyclopedia Article: Media

- R.M. Savory, Safavids, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd edition

- "The Islamic World to 1600", The Applied History Research Group, The University of Calgary, 1998, retrieved 1 October 2007

- Iran Islamic Republic, Encyclopædia Britannica retrieved 23 January 2008

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 23 January 2008 Cite error: The named reference "Britannica" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ http://www.pbase.com/k_amj/tehran_museum retrieved 27 March 2008

- J.D. Vigne, J. Peters and D. Helmer, First Steps of Animal Domestication, Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology, Durham, August 2002, ISBN 1-84217-121-6

- AT CHOGHA BONUT: THE EARLIEST VILLAGE IN SUSIANA, IRAN, by Abbas Alizadeh - The Oriental Institute and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations The University of Chicago

- http://www.iranica.com/newsite/index.isc?Article=http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/ot_grp5/ot_neolithic_age_20050106.html

- ^ "Iran, 8000–2000 BC". The Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Iranian official urges approval of Susa demarcation, http://www.payvand.com/news/08/sep/1019.html

- Ancient Near Eastern art by Dominique Collon

- Chogha Mish (Iran), By K. Kris Hirst - http://archaeology.about.com/od/cterms/g/choghamish.htm

- Research

- Cultural Heritage news agency retrieved 27 March 2008

- Yarshater, Yarshater. "Iranian history". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Islamic Republic of Iran". Solcomhouse.org. The Ozone Hole Organization. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- 5000-Y-Old Inscribed Tablets Discovered in Jiroft

- ^ "Iran, 1000 BC–1 AD". The Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Lackenbacher, Sylvie. "Elam". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- Medvedskaya, I.N. (2002). "The rise and fall of Media". International Journal of Kurdish Studies. BNET. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sicker, Martin (2000). The pre-Islamic Middle East. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 68/69. ISBN 9780275968908.

- Garthwaite, Gene R., The Persians, p. 2

- J. B. Bury, p.109.

- ^ Durant.

- Transoxiana 04: Sassanians in Africa

- Sarfaraz, pp.329-330.

- Iransaga: The art of Sassanians

- Zarinkoob, p.305.

- "Iran". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard. "Iran in history". Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- Hawting G., The First Dynasty of Islam. The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750, (London) 1986, pp. 63-64

- Cambridge History of Iran, by Richard Nelson Frye, Abdolhosein Zarrinkoub, et al. Section on The Arab Conquest of Iran and . Vol 4, 1975. London. p.46

- Biruni. الآثار الباقية عن القرون الخالية, p.35,36,48 وقتی قتبیه بن مسلم سردار حجاج، بار دوم بخوارزم رفت و آن را باز گشود هرکس را که خط خوارزمی می نوشت و از تاریخ و علوم و اخبار گذشته آگاهی داشت از دم تیغ بی دریغ درگذاشت و موبدان و هیربدان قوم را یکسر هلاک نمود و کتابهاشان همه بسوزانید و تباه کرد تا آنکه رفته رفته مردم امی ماندند و از خط و کتابت بی بهره گشتند و اخبار آنها اکثر فراموش شد و از میان رفت

- ^ Fred Astren pg.33-35

- ^ Islamic Conquest

- ^ Applied History Research Group, University of Calagary, "The Islamic World to 1600", Last accessed August 26, 2006

- ^ Tobin 113-115

- Nasr, Hoseyn; Islam and the pliqht of modern man

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition, (LINK) Cite error: The named reference "britannica" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Richard Frye, The Heritage of Persia, p. 243.

- Rayhanat al- adab, (3rd ed.), vol. 1, p. 181.

- Enderwitz, S. "Shu'ubiyya". Encyclopedia of Islam. Vol. IX (1997), pp. 513-14.

- Samanid Dynasty

- Caheb C., Cambridge History of Iran, Tribes, Cities and Social Organization, vol. 4, p305–328

- Kühnel E., in Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesell, Vol. CVI (1956)

- O.Özgündenli, "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries", Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK)

- M. Ravandi, "The Seljuq court at Konya and the Persianisation of Anatolian Cities", in Mesogeios (Mediterranean Studies), vol. 25-6 (2005), pp. 157-69

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Mongol invasion of Iran

- The Il-khanate

- Death toll#Individual battles and sieges

- Water, ch. 3

- Battuta's Travels: Part Three - Persia and Iraq

- This section incorporates test from the public domain Library of Congress Country Studies

- Islam and Iran: A Historical Study of Mutual Services

- Four Centuries of Influence of Iraqi Shiism on Pre-Safavid Iran

- Axworthy Iran: Empire of the Mind (Penguin, 2008) pp.152-167

- Axworthy p.168

- Abrahamian, Tortured Confessions (1999), p.135-6, 167, 169

- Islamic Revolution, Iran Chamber.

- The Iranian Revolution.

- Ruhollah Khomeini, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Iran Islamic Republic, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Dabashi, Theology of Discontent (1993), p.419, 443

- Shawcross, William, The Shah's Last Ride (1988), p. 110.

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.138

- Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World, Thomson Gale, 2004, p.357 (article by Stockdale, Nancy, L.)

- Keddie, Modern Iran, (2006), p.241

- PBS, American Experience, Jimmy Carter, "444 Days: America Reacts", retrieved 1 October 2007

- Guests of the Ayatollah: The Iran Hostage Crisis: The First Battle in America's War with Militant Islam, Mark Bowden, p. 127, 200

- History Of US Sanctions Against Iran Middle East Economic Survey, 26-August-2002

- National Security Archive: http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB82

- Centre for Documents of The Imposed War, Tehran. (مرکز مطالعات و تحقیقات جنگ)

- Iran, 'Public Enemy Number One'

- Federation of American Scientists :: Introduction to Chemical Weapons

- Iraqi General: US Helped Us as We Used Chemical Weapons - by Aaron Glantz

- NTI Chemical profile of Iran

- Iranian party demands end to repression

- Abrahamian, Ervand, Tortured Confessions, University of California Press, 1999, 209-228

- Massacre 1988 (Pdf)

- Memories of a slaughter in Iran

- Khomeini fatwa 'led to killing of 30,000 in Iran'

- Abrahamian, History of Modern Iran, (2008), p.182

- ^ "Who's in Charge?" by Ervand Abrahamian London Review of Books, 6 November 2008

- Treacherous Alliance : the secret dealings of Israel, Iran and the United States by Trita Pasri, Yale Universtiy Press, 2007, p.145

- Iranians protest against clerics

- Uprising in Iran

- "Iran hardliner becomes president". BBC. August 3, 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- "Behind Ahmadinejad, a Powerful Cleric". New York Times. September 9, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- http://tofoiran.packdeal.com/clips/DrIman/20060906-DrIman-CNN-225.asx

- "Iraq prime minister to visit Iran". Al Jazeera. September 9, 2006.

- Cohen: Middle East fearful of Iran Tops wrath against Israel. July 29, 2009

- Iran issues anti-nuke fatwa

- Iran, holder of peaceful nuclear fuel cycle technology

- Iran's top leader digs in heels on election, By Ramin Mostaghim. 25 Jun 2009

- Mousavi says new Ahmadinejad government 'illegitimate,' 1 July 2009

- Timeline: 2009 Iran presidential elections

References

- Books and journals

- Nasr, Hossein (1972). Sufi Essays. Suny press. ISBN 978-0-87395-389-4.

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Misplaced Pages:Copyrights for more information.

Further reading

- Abrahamian, Ervand (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521821398.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Cambridge University Press (1968–1991). Cambridge History of Iran. (8 vols.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521451485.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Daniel, Elton L. (2000). The History of Iran. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. ISBN 0313361002.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Del Guidice, Marguerite (2008). "Persia - Ancient soul of Iran". National Geographic Magazine.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|day=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Olmstead, Albert T. E. (1948). The History of the Persian Empire: Achaemenid Period. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Van Gorde, A. Christian. Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-Muslims in Iran (Lexington Books; 2010) 329 pages. Traces the role of Persians in Persia and later Iran since ancient times, with additional discussion of other non-Muslim groups.

- Benjamin Walker, Persian Pageant: A Cultural History of Iran, Arya Press, Calcutta, 1950.

External links

- Persia at the Ancient History Encyclopedia with timeline, articles, illustrations, and book references

- Iran an article by Encyclopædia Iranica

- Iran an article by Encyclopædia Britannica online by Janet Afary

- Ancient Iran an article by Encyclopædia Britannica online by Adrian David Hugh Bivar and Mark J. Dresden

- Iran chamber

- A reference about Iran A Persian reference about history, culture and nature on Iran by each city and province.

- WWW-VL History Index: Iran

- WWW-VL History Index: Iran

- History of Persia

- History of Zoroastrianism

| History of Asia | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other territories | |

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA

Categories: