This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 98.176.12.43 (talk) at 01:05, 22 November 2010 (Undid revision 396700169 by Kintetsubuffalo (talk)Self-explanatory. They supplied the hats. That helmet has a well-known shape.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:05, 22 November 2010 by 98.176.12.43 (talk) (Undid revision 396700169 by Kintetsubuffalo (talk)Self-explanatory. They supplied the hats. That helmet has a well-known shape.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Sino-German cooperation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

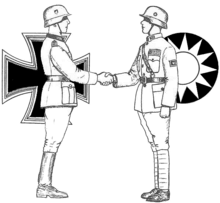

Sino-German cooperation played a great role in Chinese history of the early and mid 20th century. Sino-German cooperation played a great role in Chinese history of the early and mid 20th century. | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 中德合作 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| German name | |||||||||||

| German | Chinesisch-Deutsche Kooperation | ||||||||||

Template:ChineseText Between 1911 and 1941, cooperation between Germany and China was instrumental in modernizing the industry and the armed forces of the Republic of China prior to the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Republic of China, which succeeded the Qing Dynasty in 1912, was fraught with factional warlordism and foreign incursions. The Northern Expedition of 1928 nominally unified China under Kuomintang (KMT) control, yet Imperial Japan loomed as the greatest foreign threat. The Chinese urgency to modernize the military and its national defense industry, coupled with Germany's need for a stable supply of raw materials, put the two countries on the road of close relations from the late 1920s to the late 1930s. Although intense cooperation lasted only from the Nazi takeover of Germany in 1933 to the start of the war with Japan in 1937, and concrete measures at industrial reform started in earnest only in 1936, it had a profound effect on Chinese modernization and the capability of the Chinese to resist the Japanese in the war.

Early Sino-German relations

The earliest Sino-German trading occurred overland through Siberia, and was subject to transit taxes by the Russian government. In order to make trading more profitable, Germany decided to take the sea route and the first German merchant ships arrived in China, then under the Qing Dynasty, as part of the Royal Prussian Asian Trading Company of Emden, in the 1750s. In 1861, following China's defeat in the Second Opium War, the Treaty of Tientsin was signed, which opened formal commercial relations between various European states, including Prussia, with China.

During the late 19th century, Sino-foreign trade was dominated by the British Empire, and Otto von Bismarck was eager to establish German footholds in China to balance the British dominance. In 1885, Bismarck had the Reichstag pass a steamship subsidy bill which offered direct service to China. In the same year, he sent the first German banking and industrial survey group to evaluate investment possibilities, which led to the establishment of the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank in 1890. Through these efforts Germany was second to Britain in trading and shipping in China by 1896.

During this period, Germany did not actively pursue imperialist ambitions in China, and appeared relatively restrained compared to Britain and France. Thus, the Chinese government saw Germany as a partner in helping China in its modernization. In 1880s, German shipyard AG Vulcan Stettin built two of the most modern and powerful warships of its day—pre-dreadnought battleships Zhenyuan and Dingyuan—for the Chinese Beiyang Fleet that would see considerable action during the First Sino-Japanese War. After China's first modernization efforts apparently failed following its defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, Yuan Shi-kai requested German help in creating the Self-Strengthening Army (Chinese: 自強軍; pinyin: Zìqiáng Jūn) and the Newly Created Army (新建陸軍; Xīnjìan Lùjūn). In addition, German assistance not only concerned the military, but also industrial and technical matters. For example, in the late 1880s, the German company Krupp was contracted by the Chinese government to build a series of fortifications around Port Arthur.

Germany's relatively benign China policy as shaped by Bismarck changed under post-Bismarckian chancellors during the reign of Wilhelm II. After German naval forces were sent in response to attacks on missionaries in Shandong province, Germany negotiated in March 1898 at the Convention of Peking a ninety-nine year leasehold for Kiautschou Bay and began to develop the region. The period of the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 proved the low point in Sino-German relations and witnessed the assassination of the imperial minister to China, Baron Clemens von Ketteler and other foreign nationals. During and in the aftermath of the campaign to defeat the Boxers, troops from "each and all" participating nations engaged in plundering and looting and other excesses, but "the prime movers of the more aggressive faction were the Germans," who, with only a tiny contingent of troops then in North China wanted to exact retribution for the murder of their diplomat. On 27 July 1900, Wilhelm II spoke during departure ceremonies for the German contribution to the international relief force. He made an impromptu, but intemperate reference to the Hun invaders of continental Europe, which would later be resurrected by British propagandists to mock Germany during World War I and World War II.

Germany, however, had a major impact on the development of Chinese law. In the years preceding the fall of the Qing Dynasty, Chinese reformers began drafting a Civil Code based largely on the German Civil Code, which had already been adopted in neighboring Japan. Although this draft code was not promulgated before the collapse of the Qing dynasty, it was the basis for the Civil Code of the Republic of China introduced in 1930, which is the current civil law on Taiwan and has influenced current law in mainland China. The General Principles of Civil Law of the People's Republic of China, drafted in 1985, for example, is modeled after the German Civil Code.

In the decade preceding World War I, Sino-German relations became less engaged. One reason for this was the political isolation of Germany, as evident by the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Triple Entente of 1907. Because of this, Germany proposed a German-Chinese-American entente in 1907, but the proposal never came to fruition. In 1912 Germany granted a six million German Goldmark loan to the new Chinese Republican Government. When World War I broke out in Europe, Germany offered to return Kiautschou Bay to China in an attempt to keep their colony from falling into Allied hands. However, the Japanese preempted that move and entered the war on the side of the Triple Entente and invaded Kiautschou during the Siege of Tsingtao. As the war progressed, Germany had no active role or initiative in conducting any purposeful actions in the Far East as the country was preoccupied with the war in Europe.

On 14 August 1917, China declared war on Germany and recovered the German concessions in Hankow and Tientsin. As a reward for joining the Allies, China was promised the return of other German spheres of influence following the defeat of Germany. However, at the Paris Peace Conference, Japan's claims trumped prior promises to China and the Treaty of Versailles assigned the modern and up-to-date city of Tsingtao and the Kiautschou Bay region to Japan. Subsequent recognition of this Allied betrayal sparked the nationalistic May Fourth Movement, which is regarded as a significant event in modern Chinese history. As a result, the Beiyang government refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles.

World War I dealt a severe blow to Sino-German relations. Long established trade connections had been destroyed, financial structures and markets wrecked; of the almost three hundred German firms conducting business in China in 1913, only two remained in 1919.

Sino-German cooperation in the 1920s

The Treaty of Versailles severely limited Germany's industrial output. Its army was restricted to 100,000 men and its military production was greatly reduced. However, the treaty did not diminish Germany's place as a leader in military innovation, and many industrial firms still retained the machinery and technology to produce military hardware. Therefore, to circumvent the treaty's restrictions, these industrial firms formed partnerships with foreign nations, such as the Soviet Union and Argentina, to legally produce weapons and sell them.

After the death of Yuan Shi-kai, the central Beiyang Government collapsed and the country fell into civil war, with various warlords vying for supremacy. Therefore, many German arms producers began looking to reestablish commercial links with China to tap into its vast market for weapons and military assistance.

The Kuomintang government in Guangzhou also sought German assistance, and the German-educated Chu Chia-hua (朱家驊; Zhū Jiāhuá) emerged as the most prominent and had his hands in arranging almost all Sino-German contact from 1926 to 1944. There were several reasons other than Germany's technological expertise that made it the top candidate in Sino-foreign relations. First was that Germany, having lost all of its spheres of influence following World War I, had no imperialistic interest in China anymore, and the 1925–1926 anti-foreign protests were mainly directed at Great Britain. In addition, unlike the Soviet Union, which helped with Kuomintang reorganization and opened party membership to communists, Germany had no political interest in China that could have led to confrontations with the central government. Also, Chiang Kai-shek saw German history as something that China should emulate, as the German unification was something that Chiang thought would provide valuable lessons to his own unification of China. Thus, Germany was seen as a primary force in the "international development" of China.

In 1926, Chu Chia-hua invited Max Bauer to survey investment possibilities in China and the next year Bauer arrived in Guangzhou and was offered a post as Chiang Kai-shek's adviser. In 1928, Bauer returned to Germany to make appropriate industrial contacts for China's "reconstruction" efforts and began recruitment for a permanent advisory mission to Chiang Kai-shek in Nanking. However, Bauer was not entirely successful as many industrial firms hesitated because of China's unstable political situation, and because Bauer was persona non grata for his participation in the 1920 Kapp Putsch. In addition, Germany was still constrained by the Treaty of Versailles, making direct investment involving the military impossible. Max Bauer contracted smallpox seven months after his return to China and was buried in Shanghai. Bauer's short time in China provided the foundation for later Sino-German cooperation, as he advised on the modernization of Chinese industry and army to the Kuomintang government. He argued for the reduction of the Chinese army to produce a small but elite force, and supported opening up the Chinese market to spur German production and exports.

Sino-German cooperation in the 1930s

However, Sino-German trade slowed between 1930 and 1932 because of the Great Depression. Furthermore, Chinese industrialization was not able to progress as fast as it could because of conflicting interests between various Chinese reconstruction agencies, German industries, German import-export houses and the German Army (Reichswehr) of the Weimar Republic, all of which wanted to profit from the development. Things did not pick up speed until the 1931 Mukden Incident, in which Manchuria was annexed by Japan. This incident created the need for a concrete industrial policy that aimed to create the military and industrial capability to resist Japan. In essence, it spurred the creation of a centrally planned, national defense economy. This both consolidated Chiang's rule over the nominally unified China and hastened industrialization efforts in China.

The 1933 seizure of power by the Nazi Party further accelerated the formation of a concrete Sino-German policy. Before the Nazi rise to power, German policy in China had been contradictory, as the Foreign Ministry under the Weimar Government urged for a policy of neutrality in East Asia and discouraged the Reichswehr-industrial complex from involving directly with the Chinese government. The same feeling was shared by the German import-export houses, for fear that direct government ties would exclude them from profiting as the middleman. On the other hand, the new Nazi government's policy of Wehrwirtschaft (war economy) called for the complete mobilization of society and stockpiling of raw materials, particularly militarily important materials such as tungsten and antimony, which China could supply in bulk. Thus, from this period on, the main driving force behind Germany's China policy became that of raw materials.

In May 1933, Hans von Seeckt arrived in Shanghai and was offered the post of senior adviser to oversee economic and military development involving Germany in China. In June of that year, he submitted the Denkschrift für Marschall Chiang Kai-shek memorandum, outlining his program of industrializing and militarizing China. He called for a small, mobile, and well-equipped force as opposed to a massive but under-trained army. In addition, he provided a framework that the army is the "foundation of ruling power," that the military power rests in qualitative superiority, and that this superiority derives from the quality of its officer corps.

Von Seeckt suggested that the first steps toward achieving this framework was that the Chinese military needed to be uniformly trained and consolidated under Chiang's command, and that the entire military system must be subordinated into a centralized network like a pyramid. Toward this goal, von Seeckt proposed the formation of a "training brigade" in lieu of the German eliteheer which would propagate training to other units to create a professional, competent army, with its officer corps selected from strict military placements directed by a centralized personnel office.

In addition, with German help, China would have to build up its own defense industry because it could not rely on buying arms from abroad forever. The first step toward efficient industrialization was the centralization of not only the Chinese reconstruction agencies, but also German ones. In January 1934, the Handelsgesellschaft für industrielle Produkte, or Hapro, was created to unify all German industrial interests in China. Hapro was nominally a private company to avoid oppositions from other foreign countries. In August 1934, "Treaty for the Exchange of Chinese Raw Materials and Agricultural Products of German Industrial and Other Products" was signed in which the Chinese government would send strategically important raw material in exchange for German industrial products and development. This barter agreement was beneficial to Sino-German cooperation since China had a very high budget deficit due to military expenditures through years of civil war and was unable to secure monetary loans from the international community. The agreement that led to massive Chinese export of raw material also made Germany independent of international raw material markets. In addition, the agreement expedited not only Chinese industrialization, but also military reorganization. The agreement also specified that China and Germany were equal partners and that they were both important in this economic exchange. Having accomplished this important milestone in Sino-German cooperation, von Seeckt transferred his post to General Alexander von Falkenhausen and returned to Germany in March 1935, where he died in 1936.

Finance minister of China and Kuomintang official H.H. Kung and two other Chinese Kuomintang officials visited Germany in 1937 and were received by Adolf Hitler. Kung and a Chinese delegation took part in King George VI's coronation in 1937 (Kung was by then vice prime minister, secretary of treasury and president of Central Bank of China). After the coronation they visited Germany, invited by Hjalmar Schacht and Werner von Blomberg.

The Chinese delegacy arrived at Berlin on June 9, 1937. Kung met Hans von Mackensen on June 10 (von Neurath was visiting eastern Europe); during the meeting, Kung pointed out that Japan was not a reliable ally for Germany, as he believed that Germany had not forgotten the Japanese invasion of Tsingtao and the Pacific Islands during World War I. China was the real anti-communist state and Japan was only "flaunting". Von Mackensen promised that there would be no problems in Sino-Germany relationship so far as he and Neurath were in charge of the Foreign Ministry. Kung also met Schacht on the same day. Schacht explained to him that the anti-Comintern pact was not an German-Japanese alliance against China. Germany was glad to loan China 100 million Reichsmark and they would not do so with Japanese.

Kung visited Hermann Göring on June 11, Göring told him he thought Japan was a "Far East Italy" (referring to the fact that during World War I Italy had broken its alliance and declared war against Germany), and Germany would never trust Japan. Kung asked Göring "Which country will Germany choose as her friend, China or Japan?", and Göring said China could be a mighty power in the future and Germany would take China as friend.

Kung met Hitler on June 13. Hitler told Kung Germany had no political or territorial demands in Far East, Germany was a strong industrial country and China was a huge agricultural country; Germany's only thought on China is business. Hitler also hoped China and Japan could cooperate and Hitler could mediate any disputes between these two countries, as he mediated the disputes between Italy and Yugoslavia. Hitler also told Kung that Germany would not invade other countries, and was also not afraid of foreign invasion. If Russia dared to invade Germany, one German division could defeat two Russian corps. The only thing he (Hitler) worried about was bolshevism in eastern European states, being a threat to German interests and market. Hitler also said he admired Chiang because he built a powerful centralized government.

Kung met von Blomberg on the afternoon of June 13 and discussed the execution of 1936 HAPRO Agreement. Under this agreement, the German Ministry of War loaned China 100 million Reichsmarks to purchase German weapons and machines. In order to repay the loan, China provided Germany with tungsten and antimony.

Kung left Berlin on June 14 to visit the US, and returned to Berlin on August 10, one month after Sino-Japanese War broke out. He met von Blomberg, Schacht, von Mackensen and Ernst von Weizsäcker, asking them to mediate the war.

Germany and Chinese industrialization

In 1936, China had only about 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of railways, far lower than the 100,000 miles (160,000 km) that Sun Yat-sen had envisioned for his ambition of a modernized China. In addition, half of these were in Manchuria, which was already lost to Japan and out of Kuomintang control. The slow progress of modernizing China's transportation was because of conflicting foreign interests in China, such as the 1920 New Four-Power Consortium of British, French, American, and Japanese banking interests. This consortium aimed to regularize foreign investment in China and unanimous approval was required before any of the four could provide credit to the Chinese government for building railways. In addition, other foreign countries were hesitant to provide funding because of the depression.

However, a series of Sino-German agreements in 1934–1936 greatly accelerated railway construction in China. Major railroads were built between Nanchang, Zhejiang, and Guizhou. These fast developments were made possible because Germany needed efficient transportation to export raw materials, and because the railway lines served the Chinese government's need to build an industrial center south of the Yangtze, in the south-central provinces. In addition, these railways served important military functions. For example, the Hangzhou-Guiyang rail was built to facilitate military transport in the Yangtze delta valley, even after Shanghai and Nanking were lost. Another similar railway was the Guangzhou-Hankou network, which provided transportation between the eastern coast and the Wuhan area. This railway would later prove its worth in the early stages of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The most important industrial project from Sino-German cooperation was the 1936 Three-Year Plan, which was administered by the Chinese government's National Resources Commission and the Hapro corporation. The purpose of this plan was to create an industrial powerhouse capable of resisting Japan in the short run, and to create a center for future Chinese industrial development for the long run. It had several basic components such as the monopolization of all operations pertaining to tungsten and antimony, the construction of the central steel and machine works in provinces such as Hubei, Hunan, and Sichuan, and the development of power plants and other chemical factories. As outlined in the 1934 barter agreement, China would provide raw materials in return for German expertise and equipment in setting up these ventures. Cost overrun for these projects was partly assuaged by the fact that the price of tungsten had more than doubled between 1932 and 1936. Germany also extended RM 100 million line of credit to the Chinese government. The Three-Year Plan also introduced a class of highly educated technocrats who were trained to run these state-owned projects. At the height of this program, Sino-German exchange accounted for 17% of China's foreign trade and China was the third largest trading partner with Germany. The Three-Year Plan had many promises, but unfortunately much of its intended benefits would eventually be undermined by the breakout of full-scale war with Japan in 1937.

Germany and Chinese military modernization

Alexander von Falkenhausen was responsible for most of military training conducted as part of the deal. Original plans by von Seeckt called for a drastic reduction of the military to 60 well-equipped and well-trained divisions based on German military doctrines, but questions as to which factions would be axed remained a problem. As a whole, officer corps trained by the Whampoa Academy up until 1927 were of marginally better quality than the warlord armies, but they remained valuable to Chiang Kai-shek for sheer loyalty. Nonetheless, some 80,000 Chinese troops, in eight divisions, were trained to German standards and formed the elite of Chiang's army. These new divisions might have contributed to Chiang's determination to escalate the skirmish at Marco Polo Bridge to full-scale war. However, China was not ready to face Japan on equal terms, and Chiang's decision to pit all of his new divisions in the Battle of Shanghai, despite objections from his staff officers and von Falkenhausen himself, would cost him one-third of his best troops that took years to train. Chiang was suggested to preserve his strength to maintain order and fight later.

Von Falkenhausen recommended that Chiang fight a war of attrition with Japan as Falkenhausen calculated that Japan could never hope to win a long term war. He suggested that Chiang should hold the Yellow River line, but not attack north of that until much later in the war. Also Chiang should be prepared to give up a number of regions in northern China, including Shandong, but the retreats must be made slowly; Japan was to pay for every advance it made. He also recommended a number of fortifications to be constructed, near mining areas, coastal, river locations, and so on. Falkenhausen also advised the Chinese to establish a number of guerrilla operations (which the Communists were adept at) behind Japanese lines. These efforts would help to weaken an already militarily challenged Japan.

Von Falkenhausen also believed that it was too optimistic to expect the Chinese National Revolutionary Army (NRA) to be adequately supported by armor and heavy artillery in the war against Japan. Chinese industry was just starting to modernize and it would take a while to fully equip the NRA in the fashion of the German Army (Wehrmacht Heer). Thus, he emphasized on the creation of a mobile force that relied on small arms and adept with infiltration tactics, similar to the stormtroopers near the end of World War I. German officers were called into China as military advisers, like Lt. Col. Hermann Voigt-Ruscheweyh, who acted as adviser to the Artillery Firing School in Nanjing from 1933 to 1938.

German assistance in the military realm was not limited to personnel training and reorganization, but also involved military hardware. According to von Seeckt, around eighty percent of China's weapons output was below par or unsuitable for modern warfare. Therefore, projects were undertaken to expand and upgrade existing armories along the Yangtze River and to create new arsenals and munitions plants. For example, the Hanyang Arsenal was reconstructed during 1935–1936 to bring its standards up to date. The arsenal was to produce Maxim machine guns, various 82 mm trench mortars and the Chiang Kai-shek rifle (中正式; Zhōngzhèng Shì), which was based on the German Karabiner 98k rifle. The Chiang Kai-shek and Hanyang 88 rifles remained as the predominant firearm used by Chinese armies throughout the war. Another factory was established to produce gas masks, with plans to construct a mustard gas plant that was eventually scrapped. In May 1938, several arsenals were built in Hunan to produce 20mm, 37 mm, and 75 mm artilleries. In late 1936 a plant was built near Nanking to manufacture military optical equipment such as binoculars and sniper rifle scopes. Additional arsenals were built or upgraded to manufacture other weapons and ordnances, such as the MG-34, pack guns of different calibers, and even replacement parts for vehicles of the Leichter Panzerspähwagen series serving in the Chinese army. Several research institutes were also established under German auspices, such as the Ordnance and Arsenal Office, the Chemical Research Institute under the direction from IG Farben, and others. Many of these institutes were headed by German-returned Chinese engineers. In 1935 and 1936, China ordered a total of 315,000 of the M35 Stahlhelm, and also large numbers of Gewehr 88, 98 rifles and the C96 Broomhandle Mauser. China also imported other military hardware, such as a small number of Henschel, Junkers, Heinkel and Messerschmitt aircraft, some of them to be assembled in China, and Rheinmetall and Krupp howitzers, anti-tank and mountain guns, such as the PaK 37mm, as well as AFVs such as the Panzer I.

These modernization efforts proved their usefulness with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Although the Japanese, in the end, were able to capture the Nationalist capital at Nanjing, the process took several months with a cost far higher than either side had anticipated. Japanese frustrations at strong Chinese resistance were vented out during the Rape of Nanking (Nanjing Massacre). Despite this loss, the fact that Chinese troops could credibly challenge Japanese troops boosted the morale of the Chinese. In addition, the cost of the campaign made the Japanese reluctant to go deeper into the Chinese interior, allowing the Nationalist government to relocate China's political and industrial infrastructure into Sichuan.

End of Sino-German cooperation

The outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War on July 7, 1937 destroyed much of the progress and promises made in the nearly ten years of intense Sino-German cooperation. Besides the destruction of industries in the war, Adolf Hitler's foreign policy would prove the most detrimental to Sino-German relations. In essence, Hitler chose Japan as his ally against the Soviet Union, because Japan was militarily far more capable to resist Bolshevism. In addition, the Sino-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of August 21, 1937 definitely did not help to change Hitler's mind, despite persistent protests from the China lobby and German investors. However, Hitler did agree to have Hapro finish shipments already ordered by China, but did not allow any more orders from Nanking to be taken.

There were plans of a German-mediated peace between China and Japan, but the fall of Nanking in December 1937 effectively put an end to any mediation acceptable to the Chinese government. Therefore, all hope of a German-mediated truce was lost. In early 1938, Germany officially recognized Manchukuo as an independent nation. In April of that year, Hermann Göring banned the shipment of war materials to China and in May, German advisors were recalled to Germany at Japanese insistence.

This shift from a pro-China policy to a pro-Japan one was also damaging to German business interests, as Germany had far less economic exchange with either Japan or Manchukuo than China. Also, pro-China sentiment was also apparent in most Germans in China. For example, Germans in Hankow raised more money for the Red Cross than all other Chinese and foreign nationals in the city combined. Military advisors also wished to honor their contracts with Nanking. Von Falkenhausen was finally forced to leave at the end of June 1938, but promised Chiang that he would never reveal his work to aid the Japanese. On the other hand, Nazi Party organs in China proclaimed Japan as the last bulwark against communism in China.

Germany's newfound relationship with Japan would prove to be less than fruitful, however. Japan enjoyed a monopoly in North China and Manchukuo, and many foreign businesses were seized. German interests were treated no better than any other foreign interests. While negotiations were going on in mid-1938 to solve these economic problems, Hitler signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the Soviet Union, thereby nullifying the German-Japanese Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936, destroying further negotiations. The Soviet Union agreed to allow Germany to use the Trans-Siberian Railway to transport goods from Manchukuo to Germany. However, quantities remained low, and the lack of established contacts and networks between Soviet, German, and Japanese personnel further compounded the problem. When Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, Germany's economic goals in Asia were conclusively put to an end.

Contact between China and Germany persisted to 1941, with elements from both sides wishing to resume the cooperation, as German-Japanese alliance was not very beneficial. However, Germany's failure to conquer the United Kingdom in the Battle of Britain in mid-1940 steered Hitler away from this move. Germany signed the Tripartite Pact, along with Japan and Italy, at the end of that year. In July 1941, Hitler officially recognized Wang Jingwei's puppet government in Nanking, therefore extinguishing any hope of contact with Chiang's Chinese government which had relocated to Chungking. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, China formally joined the Allies and declared war on Germany on December 9, 1941.

Legacy

Sino-German cooperation of the 1930s was perhaps the most ambitious and successful of President Sun Yat-sen's ideal of an "international development" to modernize China. Germany's loss of territories in China following World War I, its need for raw materials, and its lack of interest in Chinese politics, advanced the rate and productiveness of their cooperation with China, as both countries were able to cooperate on the basis of equality and economic dependability, without the imperialist undertones that marred much of other Sino-foreign relations. China's urgent need for industrial development to fight an eventual showdown with Japan also precipitated this progress. Furthermore, admiration of Germany's rapid rise after its defeat in World War I and its Fascist and militaristic ideology also prompted some Chinese within the ruling circle to fashion Fascism as a quick solution to China's continuing woes of disunity and political confusion. In sum, although the period of Sino-German cooperation spanned only a short period of time, and much of its results and promises were destroyed in the war with Japan that China was far from prepared for, it had some lasting effect on China's modernization. After Kuomintang's defeat in the Chinese Civil War, the central government relocated to Taiwan. In the Republic of China on Taiwan, many government officials and ministers were trained in Germany, as were many faculties, research personnel, and military officers, such as Chiang's own adopted son Chiang Wei-kuo. Much of Taiwan's rapid post-war industrialization can be attributed to the plans and goals laid down in the Three-Year Plan of 1936.

See also

- German-trained divisions in the National Revolutionary Army

- German East Asia Squadron

- History of China

- History of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Sino-German Relations

- Warlord era

- Whampoa Military Academy

Notes

- Fleming, Peter. The Siege at Peking. New York: Dorset Press. 1990 (originally published 1959), p. 243 ISBN 0-88029-462-0

- Fleming, p. 136

- Kirby 1984, p. 11

- Chen 2002, p. 8

- Chen 2002, p. 9

- Kirby 1984, p. 9

- Ellis 1929, p. 12

- China Year Book, 1929–1930 pp. 751–753.

- For biographical information, see zh:朱家驊 (in Chinese).

- Sun Yat-sen 1953, p. 298.

- Kirby 1984, p.61.

- L'Allemagne et la Chine, Journée Industrielle, Issue Dec. 1931, Paris, 1931.

- Kirby 1984, p. 78.

- Kirby 1984, p. 106.

- Liu 1956, p. 99.

- Liu 1956, p. 94.

- Kirby 1984, p. 120.

- Kung with Hitler.

- Kung and Kuomintang with Adolf Hitler.

- Akten zur deutschen auswärtigen Politik 1918–1945/ADAP.

- Cheng Tian Fang's Memoir, volume 13. Cheng was Chinese ambassador to Germany by then.

- Cheng's Memoir, vol. 13.

- Chu 1943, p. 145.

- Fischer 1962, p. 7.

- Kirby 1984, p. 221.

- Liu 1956, p. 101.

- Wheeler-Bennet 1939, p. 8.

- Kirby 1984, p. 242.

- Kirby 1984, p. 244.

- Kirby 1984, p. 250.

References

- Chen, Yin-Ching. "Civil Law Development: China and Taiwan" (PDF). Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs. Spring 2002, Volume 2.

- China Year Book, 1929–1930 (1930). North China Daily News & Herald.

- Chu Tzu-shuang. (1943) Kuomintang Industrial Policy Chungking.

- Ellis, Howard S (1929). French and German Investments in China. Honolulu.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fischer, Martin (1962). Vierzig Jahre deutsche Chinapolitik.

{{cite book}}: Text "locationHamburg" ignored (help) - Griffith, Ike (1999). Germans and Chinese. Cal University Press.

- Kirby, William (1984). Germany and Republican China. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1209-3.

- Liu, Frederick Fu (1956). A Military History of Modern China, 1924–1949. Princeton University Press.

- Sun Yat-sen (1953). The International Development of China. Taipei: China Cultural Service.

- Wheeler-Bennet, J., ed. (1939). Documents on International Affairs. Vol. 2. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- German Military Mission to China 1928–1938

- Photos of Hitler together with Chinese delegates before end of cooperation

- 20th century in China

- 20th century in Germany

- 20th-century military alliances

- Foreign relations of Germany

- Foreign relations of the Qing Dynasty

- History of the foreign relations of the Republic of China

- Military history of the Republic of China

- Military history of China during World War II

- Military history of Germany during World War II

- National Revolutionary Army

- Military alliances involving China

- Military alliances involving the German Empire

- Military alliances involving Nazi Germany