This is an old revision of this page, as edited by V7-sport (talk | contribs) at 20:44, 2 May 2011 (Per talk, Start here, look at the diffs and decide what you want to add instead of blindly reverting and filibustering on the talk page.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:44, 2 May 2011 by V7-sport (talk | contribs) (Per talk, Start here, look at the diffs and decide what you want to add instead of blindly reverting and filibustering on the talk page.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The United States government has engaged in military and covert operations that arguably amount to state terrorism, depending on how state terrorism is defined. The U.S. has funded, trained, and harbored individuals or groups who have engaged actions targeting violence at civilians, which is arguably terrorism. Some of the states in which the U.S. has allegedly conducted or supported terror operations include the Philippines, Cuba, Chile, Guatemala, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Kosovo/Serbia Japan, Nicaragua, and Vietnam.

U.S. policy and the definition of terrorism

See also: State terrorism and Definitions of terrorismThe United States legal definition of terrorism excludes acts openly done by recognized states. According to U.S. law terrorism is defined as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience.” According to professor Mark Selden, "American politicians and most social scientists definitionally exclude actions and policies of the United States and its allies" as terrorism. There is no international consensus on a legal definition of terrorism, state-sponsored terrorism, and state terrorism.

History

General critiques

Professor William Odom, formerly President Reagan's NSA Director wrote:

"As many critics have pointed, out, terrorism is not an enemy. It is a tactic. Because the United States itself has a long record of supporting terrorists and using terrorist tactics, the slogans of today's war on terrorism merely makes the United States look hypocritical to the rest of the world."

Professor Richard Falk has argued that the U.S. and other first-world states, as well as mainstream mass media institutions, have obfuscated the true character and scope of terrorism, promulgating a one-sided view from the standpoint of first-world privilege. He has said that

- if 'terrorism' as a term of moral and legal opprobrium is to be used at all, then it should apply to violence deliberately targeting civilians, whether committed by state actors or their non-state enemies.

Falk has argued that the repudiation of authentic non-state terrorism is insufficient as a strategy for mitigating it Falk also argued that people who committed "terrorist" acts against the United States could use the Nuremberg Defense.

Daniel Schorr, reviewing Falk's Revolutionaries and Functionaries, argued that Falk's definition of terrorism hinges on some unstated definition of "permissible"; this, says Schorr, makes the judgment of what is terrorism inherently "subjective", and furthermore, he suggests, leads Falk to characterize some acts he considers impermissible as "terrorism", but others he considers permissible as merely "terroristic".

Indonesia's anti-Communist purges (1965–66)

Main article: Indonesian killings of 1965–1966Professor Ruth Blakely stated that the governments of the United States and Britain were aware of the "campaign of state terror" in Indonesia, and that they supported the regime with military aid in spite of this knowledge, and "actively encouraged" the repression of the PKI and its supporters. The common estimate of the death toll of the anti-Communist purge in Indonesia which was carried out by the Indonesian Army is 500,000.

In an article for the Spartanburg Herald-Journal, journalist Kathy Kadane wrote that senior U.S. diplomats and CIA officials compiled lists of communist operatives and provided a list of approximately 5,000 names to the Indonesian Army as it captured and annihilated the Indonesian communist party and its sympathizers. Kadane wrote that approval for the release of names put on the lists came from top U.S. embassy officials; Ambassador Marshall Green, deputy chief of mission Jack Lydman and political section chief Edward Masters.

Robert J. Martens, who from 1963 to 1966 was a political officer at the United States Embassy in Jakarta acknowledged that he had passed a lists of names to the Indonesians but contended in a letter to the editor of The Washington Post that "I and I alone decided to pass those "lists" to the non-Communist forces, I neither sought nor was given permission to do so by Ambassador Marshall Green or any other embassy official". Martens wrote: "I also categorically deny that C.I.A. or any other classified material was turned over by me. Furthermore, I categorically deny that I "headed an embassy group that spent two years compiling the lists." No one, absolutely no one, helped me compile the lists in question." He said in the letter that the lists were gathered entirely from the Indonesian Communist press and were available to everyone.

Edward Masters later told Ms. Kadane that the Indonesian military was not a group of "village idiots" and that he believed they knew how to find Communist leaders without American help. Mark Mansfield, a CIA spokesman stated: "There is no substance to the allegation that the CIA was involved in the preparation and/or distribution of a list that was used to track down and kill PKI members. It is simply not true.”

Indonesia's occupation of East Timor (1975–1999)

Main article: Indonesian occupation of East TimorIn 1975, the Ford administration, including President Ford and Henry Kissinger acquiesced Indonesia's invasion and occupation of East Timor. Ford stated to Suharto that “We will not press you on the issue. “ and Kissinger advised that it was “important whatever you do succeed quickly.” Subsequent U.S. administrations continued support to Indonesia while its army occupied East Timor. By 1980 the occupation had left more than 100,000 dead with some estimates running as high as 230,000.

Professor Ruth Blakely states that "Both the U.S. and Britain were complicit in an ongoing campaign of state terrorism by Indonesia which cost hundreds of thousands of lives. Furthermore, their economies benefited from the sale of arms which were used against East Timorese civilians."

Wars in Indochina

Main article: Korean War Main article: Vietnam WarProfessor Ruth Blakely stated the following:

The methods used by the U.S. to defeat its opponents in Indochina involved the widespread use of state terrorism. The U.S. was directly responsible for state terrorism in some cases, as in the aerial bombardment of the civilian population in Korea and the establishment of counterinsurgency programs such as the Phoenix Program in Vietnam, which involved torture and assassination of civilians suspected of supporting the opposition, and was intended to deter public support for the enemy. The U.S. was complicit in state terrorism through its support for repressive regimes, either by giving the green light to acts of state terrorism or by providing military hardware to regimes engaged in campaigns of state terrorism, as was the case in Taiwan and Indonesia. The U.S. also collaborated with those regimes through the sharing of military doctrine which advocated state terrorism, as the case of the Philippines shows

Professor Michael Stohl considers the 1972 bombings of North Vietnam, code-named Operation Linebacker II, to be an example of a type of terrorism that he calls "terrorism by coercive diplomacy" -- i.e. terrorism whose purpose is to force an opponent to agree to your demands by making their living conditions "horrible beyond endurance".

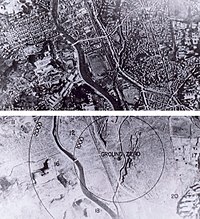

Atomic bombings of Japan (1945)

Main article: Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and NagasakiThe atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II was the first and last time a state has used nuclear weapons against people. Critics hold that it represents the single greatest act of state terrorism in the 20th century even though it was done during wartime. Those who defend the bombings argue that as a result its supposed shortening of the war, thereby preventing any possible need for an invasion, less lives were lost on both sides overall.

For scholars, the primary ethics debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, relate to whether the use of the nuclear weapons were justified. Psychologist Chris Stout and former U.S. ambassador Robert Keeley consider the atomic bombings to be a form of state terrorism, based on a definition of terrorism as the targeting of civilians to achieve a political goal.

Professor Richard A. Falk has written in detail about Hiroshima and Nagasaki as instances of state terrorism. He writes "The graveyards of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the number-one exhibits of state terrorism... Consider the hypocrisy of an Administration that portrays Qaddafi as barbaric while preparing to inflict terrorism on a far grander scale.... Any counter terrorism policy worth the name must include a convincing indictment of the First World variety.".

Professor Mark Selden, professor of sociology and history at Binghamton University and author of War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century, writes, "This deployment of air power against civilians would become the centerpiece of all subsequent U.S. wars, a practice in direct contravention of the Geneva principles, and cumulatively the single most important example of the use of terror in twentieth century warfare." Falk, Selden, and Prof. Douglas Lackey, each of whom relate the Japan bombings to what they believe was a similar pattern of state terrorism in following wars, particularly the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Cuba (1959–present)

After Fidel Castro's forces defeated Fulgencio Batista's forces, a new government was formed in Cuba on January 2, 1959. The CIA initiated a campaign of regime change in the early parts of 1959, and by the spring of 1959 was arming counter-revolutionary guerrillas inside Cuba. By winter of that year US-based Cubans were being supervised by the CIA in the orchestration of bombings and incendiary raids against Cuba. Piero Gleijeses, Jorge I. Dominguez, and Richard Kearney refer to the U.S. actions against Castro during the early 1960s as terrorism.

Cuban government officials have accused the United States government of being an accomplice and protector of terrorism against Cuba on many occasions. According to Ricardo Alarcón, President of Cuba's national assembly "Terrorism and violence, crimes against Cuba, have been part and parcel of U.S. policy for almost half a century." Testifying before the United States Senate in 1978, Richard Helms, former CIA Director, stated; "We had task forces that were striking at Cuba constantly. We were attempting to blow up power plants. We were attempting to ruin sugar mills. We were attempting to do all kinds of things in this period. This was a matter of American government policy."

The claims formed part of Cuba's $181.1 billion lawsuit in 1999 in Havana's Popular Provincial Tribunal against the United States on behalf of the Cuban people which alleged that for over 40 years, "terrorism has been permanently used by the U.S. as an instrument of its foreign policy against Cuba", and it "became more systematic as a result of the covert action program." The lawsuit detailed a history of terrorism allegedly supported by the United States. The United States has long denied any involvement in the acts named in the lawsuit.

Cuba also claims U.S. involvement in the paramilitary group Omega 7, the CIA undercover operation known as Operation 40, and the umbrella group the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations. Cuban counterterrorism investigator Roberto Hernández testified in a Miami court that the bomb attacks were "part of a campaign of terror designed to scare civilians and foreign tourists, harming Cuba's single largest industry."

In 2001, Cuban Ambassador to the UN Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla called for UN General Assembly to address all forms and manifestations of terrorism in every corner of the world, including — without exception — state terrorism. He alleged to the UN General Assembly that 3,478 Cubans have died as a result of aggressions and terrorist acts. The Ambassador however did not claim that the U.S. had committed terrorist acts. He also alleged that the United States had provided safe shelter to "those who funded, planned and carried out terrorist acts with absolute impunity, tolerated by the United States Government."

Operation Mongoose

Further information: ]An objective of the Kennedy administration was the removal of Fidel Castro from power. To this end it implemented Operation Mongoose, a U.S. program of sabotage and other secret operations against the island. Mongoose was led by Edward Lansdale in the Defense Department and William King Harvey at the CIA. Samuel Halpern, a CIA co-organizer, conveyed the breadth of involvement: "CIA and the U. S. Army and military forces and Department of Commerce, and Immigration, Treasury, God knows who else — everybody was in Mongoose. It was a government-wide operation run out of Bobby Kennedy's office with Ed Lansdale as the mastermind." The scope of Mongoose included sabotage actions against a railway bridge, petroleum storage facilities, a molasses storage container, a petroleum refinery, a power plant, a sawmill, and a floating crane. Harvard Historian Jorge Domínguez stated that "only once in thousand pages of documentation did a U.S. official raise something that resembled a faint moral objection to U.S. government sponsored terrorism." The CIA operation was based in Miami, Florida and among other aspects of the operation, enlisted the help of the Mafia to plot an assassination attempt against Fidel Castro, the Cuban president; for instance, William Harvey was one of the CIA case officers who directly dealt with John Roselli.

Dominguez wrote that Kennedy put a hold on Mongoose actions as the Cuban Missile Crisis escalated, and the "Kennedy administration returned to its policy of sponsoring terrorism against Cuba as the confrontation with the Soviet Union lessened." However, Chomsky argued that "terrorist operations continued through the tensest moments of the missile crisis," remarking that "they were formally canceled on October 30, several days after the Kennedy and Khrushchev agreement, but went on nonetheless." Accordingly, "the Executive Committee of the National Security Council recommended various courses of action, "including ‘using selected Cuban exiles to sabotage key Cuban installations in such a manner that the action can plausibly be attributed to Cubans in Cuba’ as well as ‘sabotaging Cuban cargo and shipping, and Bloc cargo and shipping to Cuba." Peter Kornbluh, senior analyst at the National Security Archive at George Washington University, raised the point that according to the documentary record, directly after the first executive committee (EXCOMM) meeting that was held on the missile crisis, Attorney General Robert Kennedy "convened a meeting of the Operation Mongoose team" expressing disappointment in its results and pledging to take a closer personal attention on the matter. Kornbluh accused RFK of taking "the most irrational position during the most extraordinary crisis in the history of U. S. foreign policy", remarking that "Not to belabor the obvious, but for chrissake, a nuclear crisis is happening and Bobby wants to start blowing things up.".

Historian Stephen G. Rabe wrote that "scholars have understandably focused on...the Bay of Pigs invasion, the U.S. campaign of terrorism and sabotage known as Operation Mongoose, the assassination plots against Fidel Castro, and, of course, the Cuban missile crisis. Less attention has been given to the state of U.S.-Cuban relations in the aftermath of the missile crisis." In contrast Rabe wrote that reports from the Church Committee reveal that from June 1963 onward the Kennedy administration intensified its war against Cuba while the CIA integrated propaganda, "economic denial", and sabotage to attack the Cuban state as well as specific targets within. One example cited is an incident where CIA agents, seeking to assassinate Castro, provided a Cuban official, Rolando Cubela Secades, with a ballpoint pen rigged with a poisonous hypodermic needle. At this time the CIA received authorization for thirteen major operations within Cuba; these included attacks on an electric power plant, an oil refinery, and a sugar mill. Rabe has written that the "Kennedy administration...showed no interest in Castro's repeated request that the United States cease its campaign of sabotage and terrorism against Cuba. Kennedy did not pursue a dual-track policy toward Cuba....The United States would entertain only proposals of surrender." Rabe further documents how "Exile groups, such as Alpha 66 and the Second Front of Escambray, staged hit-and-run raids on the island...on ships transporting goods...purchased arms in the United States and launched...attacks from the Bahamas."

Author Joan Didion has emphasized that despite the Kennedy administration's rejection of the "two track strategy," such a strategy did in effect continue for much time afterwards, characterized by the FBI being consistently engaged in investigating and prosecuting groups such as Omega 7, while the same groups received funds, arms, and support from the CIA. Eventually, in 1985, the leader of Omega 7, Eduardo Arocena, was successfully prosecuted for murder with the aid of an FBI investigation. The extent of CIA involvement in these groups has been debated by historians, and Didion relates that some of these groups were more rogue due to a distrust of the CIA. Later terrorist acts by ex-CIA operatives from the Cuba project, such as the CORU group's bombing of Cubana Flight 455 in 1976, were most likely carried out without CIA planning or knowledge as far as the public record shows.

Allegations of harboring terrorists

The Cuban revolution resulted in a large Cuban refugee community in the U.S., some of whom have conducted long-term insurgency campaigns against Cuba. and conducted training sessions at a secluded camp near the Florida Everglades. These efforts are charged to have been directly supported initially by the United States government. The failed military invasion of Cuba during the administration of John F. Kennedy at the Bay of Pigs marked the end of documented U.S. involvement.

The Cuban Government, its supporters and some outside observers have charged that the group Alpha 66, whose former secretary general Andrés Nazario Sargén acknowledged terrorist attacks on Cuban tourist spots in the 1990s and conducted training sessions at a secluded camp near the Florida Everglades, has, according to Cuba's official newspaper Granma, been supported by the National Endowment for Democracy, the United States Agency for International Development and, more directly, the CIA.

Marcela Sanchez says that the U.S. has also failed to indict or prosecute the alleged terrorists Guillermo and Ignacio Novo Sampoll, Pedro Remon, and Gaspar Jimenez. Claudia Furiati has suggested Sampol was linked to President Kennedy's assassination and plans to kill President Castro.

Luis Posada Carriles a former CIA operative, Posada has been convicted in absentia of involvement in various terrorist attacks and plots in the Western hemisphere, including involvement in the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner that killed seventy-three people and has admitted to his involvement in other terrorist plots including a string of bombings in 1997 targeting fashionable Cuban hotels and nightspots. In addition, he was jailed under accusations related to an assassination attempt on Fidel Castro in Panama in 2000, although he was later pardoned by Panamanian President Mireya Moscoso in the final days of her term.

In 2005, Posada was held by U.S. authorities in Texas on the charge of illegal presence on national territory before the charges were dismissed on May 8, 2007. His release on bail on April 19, 2007 had elicited angry reactions from the Cuban and Venezuelan governments. The U.S. Justice Department had urged the court to keep him in jail because he was "an admitted mastermind of terrorist plots and attacks", a flight risk and a danger to the community.

On September 28, 2005 a U.S. immigration judge ruled that Posada cannot be deported, finding that he faces the threat of torture in Venezuela.

Posada Carrilles is currently standing trial in El Paso, Texas, for lying to immigration authorities. The trial has been criticized internationally for not being a murder trial. However, the Obama administration's Department of Justice did add several counts to the perjury charge, relating to Posada's history of terrorism. In specific, he is accused of lying to immigration authorities about his admitted role in the 1997 tourism bombings in Cuba.

Nicaragua (1979–90)

See also: Iran-Contra affair Further information: ]Following the rise to power of the left-wing Sandinista government in Nicaragua, the Ronald Reagan administration ordered the CIA to organize and train the Contras, a right wing guerrilla group. On December 1, 1981, President Reagan signed an initial, one-paragraph "Finding" authorizing the CIA's paramilitary war against Nicaragua.

Florida State University professor, Frederick H. Gareau, has written that the Contras "attacked bridges, electric generators, but also state-owned agricultural cooperatives, rural health clinics, villages and non-combatants." U.S. agents were directly involved in the fighting. "CIA commandos launched a series of sabotage raids on Nicaraguan port facilities. They mined the country's major ports and set fire to its largest oil storage facilities." In 1984 the U.S. Congress ordered this intervention to be stopped, however it was later shown that the CIA illegally continued (See Iran-Contra affair). Professor Gareau has characterized these acts as "wholesale terrorism" by the United States.

Colombian writer and former diplomat Clara Nieto, in her book "Masters of War", charged the Reagan administration was "the paradigm of a terrorist state", remarking that this was "ironically, the very thing Reagan claimed to be fighting." Nieto charged direct CIA involvement, claiming that "the CIA launched a series of terrorist actions from the "mother ship" off Nicaragua's coast. In September 1983, she charged the agency attacked Puerto Sandino with rockets. The following month, frogmen blew up the underwater oil pipeline in the same port- the only one in the country. In October there was an attack on Pierto Corinto, Nicaragua's largest port, with mortars, rockets and grenades, blowing up five large oil and gasoline storage tanks. More than a hundred people were wounded, and the fierce fire, which could not be brought under control for two days, forced the evacuation of 23,000 people."

Historian Greg Grandin described a disjuncture between official U.S. ideals and support for terrorism. "Nicaragua, where the United States backed not a counter insurgent state but anti-communist mercenaries, likewise represented a disjuncture between the idealism used to justify U.S. policy and its support for political terrorism... The corollary to the idealism embraced by the Republicans in the realm of diplomatic public policy debate was thus political terror. In the dirtiest of Latin America's dirty wars, their faith in America's mission justified atrocities in the name of liberty." In his analysis, Grandin charged that the behavior of the U.S. backed-contras was particularly inhumane and vicious: "In Nicaragua, the U.S.-backed Contras decapitated, castrated, and otherwise mutilated civilians and foreign aid workers. Some earned a reputation for using spoons to gorge their victims eye's out. In one raid, Contras cut the breasts of a civilian defender to pieces and ripped the flesh off the bones of another."

Nicaragua vs. United States

Main article: Nicaragua vs. United StatesThe Republic of Nicaragua vs. The United States of America was a case heard in 1986 by the International Court of Justice which ruled in Nicaragua's favor, and found that the United States had violated international law. The court ruled that the U.S. was "in breach of its obligation under customary international law not to use force against another state" by direct acts of U.S. personnel and by the supporting Contra guerrillas in their war against the Nicaraguan government and by mining Nicaragua's harbors. The ICJ ordered the U.S. to pay reparations. The U.S. was not imputable for possible human rights violations done by the Contras. The case led to considerable debate concerning the issue of the extent to which state support of terrorists implicates the state itself. A consensus among scholars of international law had not been reached by the mid-2000s. The Court found that this was a conflict involving military and para-military forces and did not make a finding of state terrorism.

U.S. foreign policy critic Noam Chomsky argued that the U.S. was legally found guilty of international terrorism based on this verdict.

The World Court considered their case, accepted it, and presented a long judgment, several hundred pages of careful legal and factual analysis that condemned the United States for what it called "unlawful use of force" — which is the judicial way of saying "international terrorism" — ordered the United States to terminate the crime and to pay substantial reparations, many billions of dollars, to the victim.

— Noam Chomsky, interview on Pakistan Television

The essence of this view of U.S. actions in Nicaruaga was supported by Oscar Schachter: "hen a government provides weapons, technical advice, transportation, aid and encouragement to terrorists on a substantial scale it is not unreasonable to conclude that the armed attack is imputable to that government."

Guatemala (1954–96)

Further information: ]Professor of History, Stephen G. Rabe, wrote "in destroying the popularly elected government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman (1950-1954), the United States initiated a nearly four-decade-long cycle of terror and repression"

After the U.S.-backed coup, which toppled president Jacobo Arbenz, lead coup plotter Castillo Armas assumed power. Author and university professor, Patrice McSherry argued that with Armas at the head of government, "the United States began to militarize Guatemala almost immediately, financing and reorganizing the police and military."

In his book "State Terror and Popular Resistance in Guatemala", Michael McClintock argued that the national security apparatus Armas presided over was "almost entirely oriented toward countering subversion," and that the key component of that apparatus was "an intelligence system set up by the United States." At the core of this intelligence system were records of communist party members, pro-Arbenz organizations, teacher associations, and peasant unions which were used to create a detailed "Black List" with names and information about some 70,000 individuals that were viewed as potential subversives. It was "CIA counter-intelligence officers who sorted the records and determined how they could be put to use." McClintock argues that this list persisted as an index of subversives for several decades and probably served as a database of possible targets for the counter-insurgency campaign that began in the early 1960s. McClintock wrote:

United States counter-insurgency doctrine encouraged the Guatemalan military to adopt both new organizational forms and new techniques in order to root out insurgency more effectively. New techniques would revolve around a central precept of the new counter-insurgency: that counter insurgent war must be waged free of restriction by laws, by the rules of war, or moral considerations: guerrilla "terror" could be defeated only by the untrammeled use of "counter-terror", the terrorism of the state.

— Michael McClintock

McClintock wrote that this idea was also articulated by Colonel John Webber, the chief of the U.S. Military Mission in Guatemala, who instigated the technique of "counter-terror." Colonel Webber defended his policy by saying, "That's the way this country is. The Communists are using everything they have, including terror. And it must be met."

Utilizing declassified government documents, researchers Kate Doyle and Carlos Osorio from the research institute the National Security Archive documented that Guatemalan Colonel Byron Lima Estrada took military police and counterintelligence courses at the School of the Americas. He later served in several elite counterinsurgency units trained and equipped by the U.S. Military Assistance Program (MAP). He eventually rose to command D-2, the Guatemalan Military Intelligence services who were responsible for many of the terror tactics wielded throughout the 1980s.

School of the Americas

Main article: Western Hemisphere Institute for Security CooperationProfessor Gareau argued that the School of the Americas at Fort Benning (reorganized in 2001 as Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation), a U.S. training institution mainly for Latin American state security officials, is a terrorist training ground. He cited a UN report which states the school has "graduated 500 of the worst human rights abusers in the hemisphere." Gareau alleges that by funding, training and supervising Guatemalan 'Death Squads' Washington was complicit in state terrorism.

Defenders of the school argued that the alleged connection to human rights abusers is often weak. For example, Roberto D'Aubuisson's sole link to the SOA is that he had taken a course in Radio Operations long before El Salvador's civil war began. They also argued that no school should be held accountable for the actions of only some of its many graduates. Before coming to the current WHINSEC each student is now "vetted" by his/her nation and the U.S. embassy in that country. All students are now required to receive "human rights training in law, ethics, rule of law and practical applications in military and police operations."

Chile

Michael Stohl and George A. Lopez have accused the United States of supporting and committing State Terrorism in the period 1970-1973, during the overthrow of the socialist elected Chilean government of Salvador Allende. Stohl wrote, "In addition to nonterroristic strategies...the United States embarked on a program to create economic and political chaos in Chile...After the failure to prevent Allende from taking office, efforts shifted to obtaining his removal." Money authorized for the CIA to destabilize Chilean society, included, "financing and assisting opposition groups and right-wing terrorist paramilitary groups such as Patria y Libertad ("Fatherland and Liberty")." Project FUBELT was the codename for the secret CIA operations to undermine Salvador Allende's government and promote a military coup in Chile. In September 1973 the Allende government was overthrown in a violent military coup in which the United States is claimed to have been "intimately involved."

Professor Gareau, wrote on the subject: "Washington's training of thousands of military personnel from Chile who later committed state terrorism again makes Washington eligible for the charge of accessory before the fact to state terrorism. The CIA's close relationship during the height of the terror to Contreras, Chile's chief terrorist (with the possible exception of Pinochet himself), lays Washington open to the charge of accessory during the fact." Gareau argued that the fuller extent involved the U.S. taking charge of coordinating counterinsurgency efforts between all Latin American countries. He wrote, "Washington's service as the overall coordinator of state terrorism in Latin America demonstrates the enthusiasm with which Washington played its role as an accomplice to state terrorism in the region. It was not a reluctant player. Rather it not only trained Latin American governments in terrorism and financed the means to commit terrorism; it also encouraged them to apply the lessons learned to put down what it called "the communist threat." Its enthusiasm extended to coordinating efforts to apprehend those wanted by terrorist states who had fled to other countries in the region....The evidence available leads to the conclusion that Washington's influence over the decision to commit these acts was considerable." "Given that they knew about the terrorism of this regime, what did the elites in Washington during the Nixon and Ford administrations do about it? The elites in Washington reacted by increasing U.S. military assistance and sales to the state terrorists, by covering up their terrorism, by urging U.S. diplomats to do so also, and by assuring the terrorists of their support, thereby becoming accessories to state terrorism before, during, and after the fact."

Thomas Wright charged that Chile was an example of State Terrorism of a very open kind that did not attempt a facade of civilian governance, and that had a "September 11th effect" through the hemisphere. Wright, argued that "unlike their Brazilian counterparts, they did not embrace state terrorism as a last recourse; they launched a wave of terrorism on the day of the coup. In contrast to the Brazilians and Uruguayans, the Chileans were very public about their objectives and their methods; there was nothing subtle about rounding up thousands of prisoners, the extensive use of torture, executions following sham court-marshal, and shootings in cold blood. After the initial wave of open terrorism, the Chilean armed forces constructed a sophisticated apparatus for the secret application of state terrorism that lasted until the dictatorship's end...The impact of the Chilean coup reached far beyond the country's borders. Through their aid in the overthrow of Allende and their support of the Pinochet dictatorship, President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, sent a clear signal to all of Latin America that anti-revolutionary regimes employing repression, even state terrorism, could count on the support of the United States. The U.S. government in effect, gave a green light to Latin America's right wing and its armed forces to eradicate the left and use repression to erase the advances that workers — and in some countries, campesinos — had made through decades of struggle. This "September 11 effect" was soon felt around the hemisphere."

Prof. Gareau concluded, "The message for the populations of Latin American nations and particularly the Left opposition was clear: the United States would not permit the continuation of a Socialist government, even if it came to power in a democratic election and continued to uphold the basic democratic structure of that society."

People's Mujahedin of Iran

The People's Mujahedin of Iran, PMOI, known also as the Mujahedeen-e Khalq or MEK, is dedicated to the overthrow of the Iranian regime. Iranian government has accused the MEK of orchestrating a series of bombings inside Iran, including one attack that left the current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, partially paralyzed. Until January, 2009 the United States military protected the MEK inside its military camp and on supply runs to Baghdad, although the U.S. has listed the group as a terrorist organization since 1997.

"They're terrorists only when we consider them terrorists. They might be terrorists in everybody else's books . . . . It was a strange group of people and the leadership was extremely cruel and extremely vicious." said Lawrence Wilkerson, former Secretary of State Colin Powell's chief of staff.

In April 2007, CNN reported that the U.S. military and the International Committee of the Red Cross were protecting the People's Mujahedin of Iran, with the U.S. Army regularly escorting PMOI supply runs between Baghdad and its base, Camp Ashraf. The PMOI have been designated as a terrorist organization by the United States (since 1997), Canada, and Iran. According to the Wall Street Journal "senior diplomats in the Clinton administration say the PMOI figured prominently as a bargaining chip in a bridge-building effort with Tehran." The PMOI is also on the European Union's blacklist of terrorist organizations, which lists 28 organizations, since 2002. The enlistments included: Foreign Terrorist Organization by the United States in 1997 under the Immigration and Nationality Act, and again in 2001 pursuant to section 1(b) of Executive Order 13224; as well as by the European Union (EU) in 2002. Its bank accounts were frozen in 2002 after the September 11 attacks and a call by the EU to block terrorist organizations' funding. However, the European Court of Justice has overturned this in December 2006 and has criticized the lack of "transparency" with which the blacklist is composed. However, the Council of the EU declared on 30 January 2007 that it would maintain the organization on the blacklist. The EU-freezing of funds was lifted on December 12, 2006 by the European Court of First Instance. In 2003 the U.S. State Department included the NCRI on the blacklist, under Executive Order 13224.

According to a 2003 article by the New York Times, the U.S. 1997 proscription of the group on the terrorist blacklist was done as "a goodwill gesture toward Iran's newly elected reform-minded president, Mohammad Khatami" (succeeded in 2005 by the more conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad). In 2002, 150 members of the United States Congress signed a letter calling for the lifting of this designation. The PMOI have also tried to have the designation removed through several court cases in the U.S. The PMOI has now lost three appeals (1999, 2001 and 2003) to the U.S. government to be removed from the list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations, and its terrorist status was reaffirmed each time. The PMOI has continued to protest worldwide against its listing, with the overt support of some U.S. political figures.

Past supporters of the PMOI have included Rep. Tom Tancredo (R-CO), Rep. Bob Filner, (D-CA), and Sen. Kit Bond (R-MO), and former Attorney General John Ashcroft, "who became involved with the while a Republican senator from Missouri." In 2000, 200 U.S. Congress members signed a statement endorsing the organization's cause.

Philippines

In "The Terrorist Foundations of US Foreign Policy", Professor of International Law Richard Falk argues that during the Spanish American War, when the U.S. was "confronted by a nationalistic resistance movement in the Philippines," American forces were responsible for state terrorism. Falk relates that "as with the wars against native American peoples, the adversary was demonized (and victimized). In the struggle, U.S. forces, with their wide margin of military superiority, inflicted disproportionate casualties, almost always a sign of terrorist tactics, and usually associated with refusal or inability to limit political violence to a discernible military opponent. The dispossession of a people from their land almost always is a product of terrorist forms of belligerency. In contrast, interventions in Central and South America in the area of so-called "Gunboat Diplomacy" were generally not terrorist in character, as little violence was required to influence political struggle for ascendancy between competing factions of an indigenous elite."

In "Instruments of Statecraft" , human rights researcher Michael McClintock described the intensification of the U.S. role during the Hukbalahap rebellion in 1950, when concerns about a perceived communist-led Huk insurgency prompted sharp increases in military aid and a reorganization of tactics towards methods of guerrilla warfare. McClintock describes the role of U.S. "advisers" to the Philippine Minister of National Defense, Ramon Magsaysay, remarking that they "adroitly managed Magsaysay's every move." Air Force Lt. Col. Edward Geary Lansdale was a psywar propaganda specialist who became the close personal adviser and confidant of Magsaysay. The forte of another key adviser, Charles Bohannan, was guerrilla warfare. McClintock cites several examples to demonstrate that "terror played an important part" in the psychological operations under U.S. guidance. Those psywar operations that utilized terror included theatrical displays involving the exemplary display of dead Huk bodies in an effort to incite fear in rural villagers. In another psywar operation described by Lansdale, Philippine troops engaged in nocturnal captures of individual Huks. They punctured the necks of the victims and drained the corpses of blood, leaving the bodies to be discovered when daylight came, so as to play upon fears associated with the local folklore of the Asuang, or vampire.

For McClintock, this Philippines episode is particularly important because of its formative influence on U.S. counterinsurgency doctrine. In his essay, American Doctrine and State Terror, McClintock explained that U.S. Army instruction manuals of the 1960s concerning 'counterterrorism' often referred to "the particular experiences of the Philippines and Vietnam." Noting that tactics similar to those used during the Huk Rebellion (from 1946–54) in the Philippines were cited in the manuals, he elaborated that the "Department of the Army's 1976 psywar publication, DA Pamphlet 525-7-1, refers to some of the classic counterterror techniques and account of the practical application of terror. These include the capture and murder of suspected guerillas in a manner suggesting the deed was done by legendary vampires (the 'asuang'); and a prototypical "Eye of God" technique in which a stylized eye would be painted opposite the house of a suspect."

See also

- Operation Northwoods

- War crimes and the United States

- Torture and the United States

- CIA sponsored regime change

- Overseas expansion of the United States

- Overseas interventions of the United States

- American imperialism

- United States military aid

- United States Foreign Military Financing

- Human rights in the United States

- United States Agency for International Development

References

-

- Ball, Matthew (2004). "Terroris, Human rights, Social justice, Freedom and Democracy: some considerations for the legal and justice professionals of the 'Coalition of the Willing'". QUT Law & Justice Journal. Archived from the original on 2010-01-26. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- "The role of lawyers in defending the democratic rights of the people". International Association of People's Lawyers. November 7, 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - San Juan, Jr., E. (April 28, 2007). "Filipina Militants Indict Bush-Arroyo for Crimes Against Humanity". Asian Human Rights Commission. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- "Venezuelan Leader Lashes at US in UN Speech". Agence France-Presse. September 16, 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- "Security Council considers Nicaraguan complaint against United States, takes no action". United Nations. November, 1986. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - San Juan, Jr., E. (September 18, 2006). "Class Struggle and Socialist Revolution in the Philippines: Understanding the Crisis of U.S. Hegemony, Arroyo State Terrorism, and Neoliberal Globalization". Monthly Review Foundation. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- Simbulan, Roland G. (May 18, 2005). "The Real Threat". Seminar. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- Piszkiewicz, Dennis (November 30, 2003). Terrorism's War with America: A History. Praeger Publishers. p. 224. ISBN 978-0275979522.

- Cohn, Marjorie (March 22, 2002). "Understanding, responding to, and preventing terrorism" (Reprint). Arab Studies Quarterly. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- Halliday, Dennis (July 3, 2005). "The UN and its conduct during the invasion and occupation of Iraq". Centre for Research on Globalization. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- "Noam Chomsky Interview on CBC". Hot Type. 2003-12-09. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Michael Howard, George J. Andreopoulos, Mark R. Shulman (1997). The Laws of War: Constraints on Warfare in the Western World. Yale University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780300070620.

Michael Walzer has argued that Hiroshima was not a case of supreme emergency, but rather an act of political terror.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tony Coady (2007-11-14). "A just cause doesn't excuse indiscriminate killing". The Age. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

Although there were some genuine military targets in Hiroshima, the atomic bomb was not needed to destroy them. If we think of terrorism as the deliberate killing of the innocent, then the bombing was an act of terrorism far greater than any single act of terrorism perpetrated since by non-state agents.

- “Congress' definition of terrorism excludes most state sponsored violence against civilians” http://www.examiner.com/law-and-politics-in-arlington/congress-definition-of-terrorism-excludes-most-state-sponsored-violence-against-civilians

- "the war on terrorism is necessarily sub-national in character because terrorists are by most definitions not state actors." http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/archives_roll/2003_01-03/essay_2and3/essay2_kenney.html

- http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php?option=com_rokzine&view=article&id=34

- http://www.state.gov/s/ct/rls/crt/2006/82739.htm

- http://www.nctc.gov/site/other/definitions.html

- http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/422/usc_sec_22_00002656---f000-.html

- Selden P.4 http://books.google.com/books?id=D0icvm2EQLIC&pg=PA4&dq=American+Politicians+and+most+social+scientists+definitionally+exclude+actions+and+policies+of+the+United+States+and+it’s+allies&hl=en&ei=G6RETYGMJo26sQPX7f3iCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCcQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=29633 http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=31267

- http://english.pravda.ru/opinion/columnists/01-12-2010/116016-UN_unable_to_define_terrorism-0/

- http://www.un.org/terrorism/ruperez-article.html

- American Hegemony How to Use It, How to Lose at Docstoc

- ^ Falk, Richard (1988). Revolutionaries and Functionaries: The Dual Face of Terrorism. Dutton.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Falk, Richard (January 28, 2004). "Gandhi, Nonviolence and the Struggle Against War". The Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- Falk, Richard (1986-06-28). "Thinking About Terrorism". The Nation. 242 (25): 873–892.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "The Politics of Violence", Daniel Schorr, 1 May 1988.

- Blakely, Ruth (2009). State terrorism and neoliberalism: the North in the South. Taylor & Francis. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9780415462402.

- Robert Cribb, ed. The Indonesian Killings of 1965-1966: Studies from Java and Bali (Clayton, Vic: Monash papers on Southeast Asia, no. 21, 1990), p.12

- http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CEFDA1431F931A25754C0A966958260

- San Francisco Examiner, May 20, 1990; Washington Post, May 21, 1990.

- Kadane, Kathy (1990-05-20). "Ex-agents say CIA compiled death lists for Indonesians". San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco.

{{cite news}}: External link in|author= - http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CEFDA1431F931A25754C0A966958260

- http://www.namebase.org/kadane.html

- http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB62/doc4.pdf (pg.9-10)

- http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB62/#18

- http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/35878.htm

- ^ Blakely, Ruth (2009). State terrorism and neoliberalism: the North in the South. Taylor & Francis. p. 91. ISBN 9780415462402.

- Stohl, Michael (1988). The Politics of Terrorism. CRC Press. p. 279. ISBN 9780824778149.

- ^ Frey, Robert S. (2004). The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond. University Press of America. ISBN 0761827439. Reviewed at: Rice, Sarah (2005). "The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond (Review)". Harvard Human Rights Journal. 18.

- ^ Dower, John (1995). "The Bombed: Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Memory". Diplomatic History. 19 (2).

- See: Walker, J. Samuel (2005). "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground". Diplomatic History. 29 (2): 334.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Chris E. Stout (2002), The Psychology of Terrorism: Clinical aspects and responses Psychological dimensions to war and peace, Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 105–7, ISBN 0275978664,

Surely if targeting civilians is a defining characteristic, then the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki would qualify as state terrorism.

- Robert V. Keeley (December 2002), "Trying to Define Terrorism", Middle East Policy, 9 (1), John Wiley & Sons: 33–39 ,

Terrorism is also used in nation-state wars, for example in the wholesale and indiscriminate bombings of civilians living in cities – a tactic used by both sides in World War II – culminating in the atom bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a deliberate and successful attempt to end the war quickly by threatening the extinction of populations. How acute the problem of definitions is becomes manifest when anyone who tries to explain these atom bombings as acts of state terrorism in wartime is pilloried as anti-American if not worse.

- Falk, Richard (28 January 2004). "Gandhi, Nonviolence and the Struggle Against War". The Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- Selden, Mark (2002-09-09). "Terrorism Before and After 9-11". Znet. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Selden, War and State Terrorism.

- cuba and the us.p65

- ^ Chomsky, Noam. Hegemony or Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance, Henry Holt and Company, 80.

- Sheldon M. Stern (2003). Averting 'the final failure': John F. Kennedy and the secret Cuban Missile Crisis meetings. Stanford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780804748469.

- Richard Kearney (1995). States of mind: dialogues with contemporary thinkers on the European mind. Manchester University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780719042621.

- Rodríguez, Javier. "The United States is an accomplice and protector of terrorism, states Alarcón". Granma. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- "Terrorism organized and directed by the CIA". Granma. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- Landau, Saul (February 13, 2003). "Interview with Ricardo Alarcón". Transnational Institute. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- House Select Committee on Assassinations Report, Volume IV, page 125. September 22, 1978

- Wood, Nick (September 16, 1999). "Cuba's case against Washington". Workers World. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- "Cuba sues U.S. for billions, alleging 'war' damages". CNN. June 2, 1999. Archived from the original on 2007-03-10. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ Sanchez, Marcela (September 3, 2004). "Moral Misstep". The Washington Post.

- Investigator from Cuba takes stand in spy trial Miami Herald

- ^ Cuba Statement to the United Nations 2001 since the Cuban revolution

- Domínguez, Jorge I. "The @#$%& Missile Crisis (Or, What was 'Cuban' about U.S. Decisions during the Cuban Missile Crisis.Diplomatic History: The Journal of the Society for Historians of Foreign Relations, Vol. 24, No. 2, (Spring 2000): 305-15.)

- James G. Blight, and Peter Kornbluh, eds., Politics of Illusion: The Bay of Pigs Invasion Reexamined. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner, 1999, 125)

- ^ Domínguez, Jorge I. "The @#$%& Missile Crisis (Or, What was 'Cuban' about U.S. Decisions during the Cuban Missile Crisis)." Diplomatic History: The Journal of the Society for Historians of Foreign Relations, Vol. 24, No. 2, (Spring 2000): 305-15.

- Jack Anderson (1971-01-18). "6 Attempts to Kill Castro Laid to CIA". The Washington Post.

- James G. Blight, and Peter Kornbluh, eds., Politics of Illusion: The Bay of Pigs Invasion Reexamined. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner, 1999, 125

- ^ Stephen G. Rabe -Presidential Studies Quarterly. Volume: 30. Issue: 4. 2000,714

- Didion, Joan (1987). Miami. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ Alpha 66 says it carried out bomb attacks Cuba solidarity

- Bohning,Don. The Castro Obsession: U.S.Covert Operations Against Cuba 1959-1965, Potomac Books,137-138

- An Era of Exiles Slips Away. The Los Angeles Times.

- Righteous Bombers? by Kirk Nielsen, Miami New Times, December 5, 2002

- Furiati, Claudia (1994-10). ZR Rifle : The Plot to Kill Kennedy and Castro (2nd ed.). Ocean Press (AU). p. 164. ISBN 1875284850.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Selsky, Andrew O. (May 4, 2007). "Link found to bombing". Associated Press.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Castro: U.S. to free 'monster' Posada, Miami Herald, Wed, April 11, 2007.

- Organizations Demand Cuban Militant's Arrest

- U.S. tiptoes between terror, Castro's policies

- ^ U.S. criticized as Cuban exile is freed

- U.S. embarrassed by terror suspect Guardian online.

- The Confessions of Luis Posada Carriles

- Push to free convicted Cuban spies reaches D.C., Miami Herald, September 22, 2006

- No deportation for Cuban militant (BBC)

- "The Iran-Contra Affair 20 Years On: Documents Spotlight Role of Reagan, Top Aides". The National Security Archive. 2006-11-24.

-

Gareau, Frederick H. (2004). State Terrorism and the United States. London: Zed Books. pp. 16 & 166. ISBN 1-84277-535-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Nieto, Clara. Masters of War: Latin America and United States Aggression from the Cuban Revolution Through the Clinton Years, Seven Stories Press, 2003, 343-345

- Grandin, Greg. Empire's Workshop: Latin America, The United States and the Rise of the New Imperialism, Henry Holt & Company 2007, 89

- Grandin, Greg. Empire's Workshop: Latin America, The United States and the Rise of the New Imperialism, Henry Holt & Company 2007, 90

- Official name: Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicar. v. U.S.), Jurisdiction and Admissibility, 1984 ICJ REP. 392 June 27, 1986.

- ^ Jackson Nyamuya Maogoto (2005). Battling terrorism: legal perspectives on the use of force and the war on terror. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 156, 157. ISBN 9780754644071.

- Hansen, Suzy (January 16, 2002). "Noam Chomsky". Salon.com. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- Chomsky, Noam (May 19, 2002). "Who Are the Global Terrorists?". Znet. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- "On the War in Afghanistan Noam Chomsky interviewed by Pervez Hoodbhoy". chomsky.info. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- Stephen G. Rabe (2003). Managing the Counterrevolution: The United States and Guatemala, 1954-1961 (review). The Americas. p. Volume 59, Number 4.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - J. Patrice McSherry. "The Evolution of the National Security State: The Case of Guatemala." Socialism and Democracy. Spring/Summer 1990, 133.

- "About Michael McClintock". Human Rights First. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- Michael McClintock. The American Connection Volume 2: State Terror and Popular Resistance in Guatemala. London: Zed Books Ltd., 1985, pp. 2, 32.

- McClintock 32-33.

- McClintock 33.

- McClintock 54.

- McClintock 61.

- "Colonel Byron Disrael Lima Estrada". George Washington University NSA Archive (Republished).

-

Gareau, Frederick H. (2004). State Terrorism and the United States. London: Zed Books. pp. 22–25 and pp61-63. ISBN 1-84277-535-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Paul Mulshine. "The War in Central America Continues". Archived from the original on 19 December 2002. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- "Teaching democracy at the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation"

- Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. "FAQ".

- Center for International Policy. "Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation". Retrieved May 6, 2006.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "The State as Terrorist: The Dynamics of Governmental Violence and Repression" by Prof. Michael Stohl, and Prof. George A. Lopez; Greenwood Press, 1984. Page 51

- State Terrorism and the United States: From Counterinsurgency to the War on Terrorism by Frederick H. Gareau, Page78-79.

- ^ State Terrorism and the United States: From Counterinsurgency to the War on Terrorism by Frederick H. Gareau, Page 87.

- Wright, Thomas C. State Terrorism and Latin America: Chile, Argentina, and International Human Rights, Rowman & Littlefield, page 29

- ^ McClatchy Newspapers, December 31, 2008, "Cult-like Iranian Militant Group Worries About its Future in Iraq"

- Ware, Michael (2007). "U.S. protects Iranian opposition group in Iraq". CNN website, April 6, 2007. CNN. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

- "COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/847/CFSP" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. L 314: 44. 2005.

- "Chapter 6 -- Terrorist Organizations". US Department of State. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- Andrew Higgins and Jay Solomon (2006-11-29), Iranian Imbroglio Gives New Boost To Odd Exile Group, Wall Street Journal

- Défense des Moudjahidines du peuple, Yves Bonnet, former director of the French RG intelligence agency Template:Fr icon

- Council Decision, Council of the European Union, December 21, 2005

- Terrorisme: la justice européenne appelle l'UE à justifier sa liste noire, Radio France International, December 12, 2006 Template:Fr icon

- EU’s Ministers of Economic and Financial Affairs’ Council violates the verdict by the European Court, NCRI website, February 1, 2007.

- European Council is not above the law, NCRI website, February 2, 2007

- http://curia.europa.eu/en/actu/communiques/cp06/aff/cp060097en.pdf

- U.S. State Dept press statement by Tom Casey, Acting Spokesman, August 15, 2003

- Rubin, Elizabeth, New York Times. "The Cult of Rajavi". Retrieved 2006-04-21. Template:En icon

- "U.S. Congressman Tom Tancredo: Mujahedin offers hope for a new Iran". Rocky Mountain News. 2003-01-07.

- Nigel Brew (2003). "Behind the Mujahideen-e-Khalq (MeK)". Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Group, Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, Argued April 2, 2004 Decided July 9, 2004, No. 01-1480: National Council of Resistance of Iran v. Department of State

- Michael Isikoff, "Ashcroft's Baghdad Connection: Why the attorney general and others in Washington have backed a terror group with ties to Iraq", Newsweek (26 September 2002).

- Angela Woodall (2005). "Group on U.S. terror list lobbies hard". United Press International. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- Michael Isikoff & Mark Hosenball (2004). "Shades of Gray". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- Falk, Richard. Terrorist Foundations of US Foreign Policy, in Western State Terrorism, Alexander George, ed.,Polity Press,110

- McClintock, Michael. American Doctrine and State Terror in Western State Terrorism. Alexander George, ed., Polity Press, 134

Further reading

- Alexander, George (1991). Western State Terrorism. Polity Press. p. 276. ISBN 9780745609317.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Blum, William (1995). Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II. Common Courage Press. p. 457. ISBN 1-56751-052-3.

- Campbell, Bruce B., and Brenner,Arthur D.,eds. 2000. Death Squads in Global Perspective: Murder with Deniability. New York: St. Martin's Press

- Chomsky, Noam (1988). The Culture of Terrorism. South End Press. p. 269. ISBN 9780896083349.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Churchill, Ward (2003). On The Justice of Roosting Chickens. AK Press. p. 309. ISBN 1902593790.

- Menjívar, Cecilia and Rodríguez,Néstor, editors, When States Kill:Latin America, the U.S., and Technologies of Terror, University of Texas Press 2005,isbn=978-0-292-70647-7

- Perdue, William D. (August 7, 1989). Terrorism and the State: A Critique of Domination Through Fear. Praeger Press. p. 240. ISBN 9780275931407.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Pilger, John (December 12, 2002). "Bush Terror Elite Wanted 9/11 to Happen". Third World Traveler. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- Selden,, Mark, editor (November 28, 2003). War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0742523913.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sluka,, Jeffrey A., editor (1999). Death Squad: The Anthropology of State Terror. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1711-7.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Understanding Terrorism". Public Broadcasting Service. August 15, 1997. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- Vann, Bill (November 21, 2001). "Bush nominee linked to Latin American terrorism". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- Wright,, Thomas C. (February 28, 2007). State Terrorism in Latin America: Chile, Argentina, and International Human Rights. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0742537217.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

External links

- “Hope and Memory”. 1801-2004 timeline of 163 U.S. interventions. Adbusters.

- Paper argues that U.S. State Terrorism is a function of the global capitalist economy, described as Imperialism.

- U.S. Terrorism in Vietnam a review of War Without Fronts: The USA in Vietnam by Bernd Greiner