This is an old revision of this page, as edited by JJL (talk | contribs) at 04:51, 9 June 2011 (this is clearly advocacy--"death" is a highly charged term here and not a medical one (does an embryo 'die'?)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:51, 9 June 2011 by JJL (talk | contribs) (this is clearly advocacy--"death" is a highly charged term here and not a medical one (does an embryo 'die'?))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Medical condition

| Abortion | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by the removal or expulsion of a fetus or embryo from the uterus. An abortion can occur spontaneously due to complications during pregnancy or can be induced in humans and other species. In the context of human pregnancies, an abortion induced to preserve the health of the gravida (pregnant female) is termed a therapeutic abortion, while an abortion induced for any other reason is termed an elective abortion. The term abortion most commonly refers to the induced abortion of a human pregnancy, while spontaneous abortions are usually termed miscarriages.

Abortion has a low risk of maternal mortality except for abortions performed unsafely, which result in 70,000 deaths and 5 million disabilities per year globally. Abortions are unsafe when performed by persons without the proper skills or outside of a medically safe environment. An estimated 42 million abortions are performed annually with 20 million of those abortions done unsafely around the world. Forty percent of the world's women are able to access therapeutic and elective abortions within gestational limits.

Abortion has a long history and has been induced by various methods including herbal abortifacients, the use of sharpened tools, physical trauma, and other traditional methods. Contemporary medicine utilizes medications and surgical procedures to induce abortion. The legality, prevalence, cultural status, and religious status of abortion vary substantially around the world. In many parts of the world there is prominent and divisive public controversy over the ethical and legal issues of abortion. Abortion and abortion-related issues feature prominently in the national politics in many nations, often involving the opposing pro-life and pro-choice worldwide social movements (both self-named). Incidence of abortion has declined worldwide as access to family planning education and contraceptive services has increased.

Types

Induced

More than one third of the approximately 205 million pregnancies that occur each year worldwide are unintended and about 20% of them end in induced abortion. A pregnancy can be intentionally aborted in several ways. The manner selected often depends upon the gestational age of the embryo or fetus, which increases in size as the pregnancy progresses. Specific procedures may also be selected due to legality, regional availability, and doctor-patient preference. Reasons for procuring induced abortions are typically characterized as either therapeutic or elective. An abortion is medically referred to as a therapeutic abortion when it is performed to:

- save the life of the pregnant woman;

- preserve the woman's physical or mental health;

- terminate pregnancy that would result in a child born with a congenital disorder that would be fatal or associated with significant morbidity; or

- selectively reduce the number of fetuses to lessen health risks associated with multiple pregnancy.

An abortion is referred to as elective when it is performed at the request of the woman "for reasons other than maternal health or fetal disease."

Spontaneous

Main article: MiscarriageSpontaneous abortion (also known as miscarriage) is the expulsion of an embryo or fetus due to accidental trauma or natural causes before approximately the 22nd week of gestation; the definition by gestational age varies by country. Most miscarriages are due to incorrect replication of chromosomes; they can also be caused by environmental factors. A pregnancy that ends before 37 weeks of gestation resulting in a live-born infant is known as a "premature birth". When a fetus dies in utero after about 22 weeks, or during delivery, it is usually termed "stillborn". Premature births and stillbirths are generally not considered to be miscarriages although usage of these terms can sometimes overlap.

Between 10% and 50% of pregnancies end in clinically apparent miscarriage, depending upon the age and health of the pregnant woman. Most miscarriages occur very early in pregnancy, in most cases, they occur so early in the pregnancy that the woman is not even aware that she was pregnant. One study testing hormones for ovulation and pregnancy found that 61.9% of conceptuses were lost prior to 12 weeks, and 91.7% of these losses occurred subclinically, without the knowledge of the once pregnant woman.

The risk of spontaneous abortion decreases sharply after the 10th week from the last menstrual period (LMP). One study of 232 pregnant women showed "virtually complete by the end of the embryonic period" (10 weeks LMP) with a pregnancy loss rate of only 2 percent after 8.5 weeks LMP.

The most common cause of spontaneous abortion during the first trimester is chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo/fetus, accounting for at least 50% of sampled early pregnancy losses. Other causes include vascular disease (such as lupus), diabetes, other hormonal problems, infection, and abnormalities of the uterus. Advancing maternal age and a patient history of previous spontaneous abortions are the two leading factors associated with a greater risk of spontaneous abortion. A spontaneous abortion can also be caused by accidental trauma; intentional trauma or stress to cause miscarriage is considered induced abortion or feticide.

Methods

Medical

Main article: Medical abortion"Medical abortions" are non-surgical abortions that use pharmaceutical drugs, categorically called abortifacients. In 2005, medical abortions constituted 13% of all abortions in the United States; in 2010 the figure increased to 17%. Combined regimens include methotrexate or mifepristone, followed by a prostaglandin (either misoprostol or gemeprost: misoprostol is used in the U.S.; gemeprost is used in the UK and Sweden.) When used within 49 days gestation, approximately 92% of women undergoing medical abortion with a combined regimen completed it without surgical intervention. Misoprostol can be used alone, but has a lower efficacy rate than combined regimens. In cases of failure of medical abortion, vacuum or manual aspiration is used to complete the abortion surgically.

Surgical

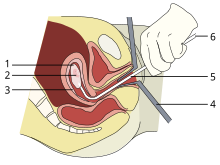

1: Amniotic sac

2: Embryo

3: Uterine lining

4: Speculum

5: Vacurette

6: Attached to a suction pump

In the first 12 weeks, suction-aspiration or vacuum abortion is the most common method. Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) abortion consists of removing the fetus or embryo, placenta and membranes by suction using a manual syringe, while electric vacuum aspiration (EVA) abortion uses an electric pump. These techniques are comparable, and differ in the mechanism used to apply suction, how early in pregnancy they can be used, and whether cervical dilation is necessary. MVA, also known as "mini-suction" and "menstrual extraction", can be used in very early pregnancy, and does not require cervical dilation. Surgical techniques are sometimes referred to as 'Suction (or surgical) Termination Of Pregnancy' (STOP). From the 15th week until approximately the 26th, dilation and evacuation (D&E) is used. D&E consists of opening the cervix of the uterus and emptying it using surgical instruments and suction.

Dilation and curettage (D&C), the second most common method of surgical abortion, is a standard gynecological procedure performed for a variety of reasons, including examination of the uterine lining for possible malignancy, investigation of abnormal bleeding, and abortion. Curettage refers to cleaning the walls of the uterus with a curette. The World Health Organization recommends this procedure, also called sharp curettage, only when MVA is unavailable.

Other techniques must be used to induce abortion in the second trimester. Premature delivery can be induced with prostaglandin; this can be coupled with injecting the amniotic fluid with hypertonic solutions containing saline or urea. After the 16th week of gestation, abortions can be induced by intact dilation and extraction (IDX) (also called intrauterine cranial decompression), which requires surgical decompression of the fetus's head before evacuation. IDX is sometimes called "partial-birth abortion," which has been federally banned in the United States. A hysterotomy abortion is a procedure similar to a caesarean section and is performed under general anesthesia. It requires a smaller incision than a caesarean section and is used during later stages of pregnancy.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has recommended that an injection be used to stop the fetal heart during the first phase of the surgical abortion procedure to ensure that the fetus is not born alive.

Other methods

Historically, a number of herbs reputed to possess abortifacient properties have been used in folk medicine: tansy, pennyroyal, black cohosh, and the now-extinct silphium (see history of abortion). The use of herbs in such a manner can cause serious—even lethal—side effects, such as multiple organ failure, and is not recommended by physicians.

Abortion is sometimes attempted by causing trauma to the abdomen. The degree of force, if severe, can cause serious internal injuries without necessarily succeeding in inducing miscarriage. Both accidental and deliberate abortions of this kind can be subject to criminal liability in many countries. In Southeast Asia, there is an ancient tradition of attempting abortion through forceful abdominal massage. One of the bas reliefs decorating the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia depicts a demon performing such an abortion upon a woman who has been sent to the underworld.

Reported methods of unsafe, self-induced abortion include misuse of misoprostol, and insertion of non-surgical implements such as knitting needles and clothes hangers into the uterus. These methods are rarely seen in developed countries where surgical abortion is legal and available.

Complications

See also: Health risks of unsafe abortionAbortion, when legally performed in developed countries, is among the safest procedures in medicine. In such settings, risk of maternal death is between 0.2–1.2 per 100,000 procedures. In comparison, by 1996, mortality from childbirth in developed countries was 11 times greater. Unsafe abortions (defined by the World Health Organization as those performed by unskilled individuals, with hazardous equipment, or in unsanitary facilities) carry a high risk of maternal death and other complications. For unsafe procedures, the mortality rate has been estimated at 367 per 100,000 (70,000 women per year worldwide).

Physical health

Surgical abortion methods, like most minimally invasive procedures, carry a small potential for serious complications.

Surgical abortion is generally safe and the rate of major complications is low but varies depending on how far pregnancy has progressed and the surgical method used. Concerning gestational age, incidence of major complications is highest after 20 weeks of gestation and lowest before the 8th week. With more advanced gestation there is a higher risk of uterine perforation and retained products of conception, and specific procedures like dilation and evacuation may be required.

Concerning the methods used, general incidence of major complications for surgical abortion varies from lower for suction curettage, to higher for saline instillation. Possible complications include hemorrhage, incomplete abortion, uterine or pelvic infection, ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, misdiagnosed/unrecognized ectopic pregnancy, hematometra (in the uterus), uterine perforation and cervical laceration. Use of general anesthesia increases the risk of complications because it relaxes uterine musculature making it easier to perforate.

Women who have uterine anomalies, leiomyomas or had previous difficult first-trimester abortion are contraindicated to undertake surgical abortion unless ultrasonography is immediately available and the surgeon is experienced in its intraoperative use. Abortion does not impair subsequent pregnancies, nor does it increase the risk of future premature births, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, or miscarriage.

In the first trimester, health risks associated with medical abortion are generally considered no greater than for surgical abortion.

Although some epidemiological studies suggest an association between abortion and breast cancer, the World Health Organization has concluded from large cohort studies that there is "no consistent effect of first trimester induced abortion upon a woman's risk of breast cancer later in life". The National Cancer Institute, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and other major medical bodies have concluded that abortion does not cause breast cancer.

Mental health

Main article: Abortion and mental healthNo scientific research has demonstrated that abortion is a cause of poor mental health in the general population. However there are groups of women who may be at higher risk of coping with problems and distress following abortion. Some factors in a woman's life, such as emotional attachment to the pregnancy, lack of social support, pre-existing psychiatric illness, and conservative views on abortion increase the likelihood of experiencing negative feelings after an abortion. The American Psychological Association (APA) concluded that abortion does not lead to increased mental health problems.

Some proposed negative psychological effects of abortion have been referred to by pro-life advocates as a separate condition called "post-abortion syndrome." However, the existence of "post-abortion syndrome" is not recognized by any medical or psychological organization.

Incidence

There are two commonly used methods of measuring incidence of abortion:

- Abortion rate - number of abortions per 1000 women between 15 and 44 years of age

- Abortion ratio - number of abortions out of 100 known pregnancies (excluding miscarriages and stillbirths)

The number of abortions performed worldwide has decreased between 1995 and 2003 from 45.6 million to 41.6 million, which means a decrease in abortion rate from 35 to 29 per 1000 women. The greatest decrease has occurred in the developed world with a drop from 39 to 26 per 1000 women in comparison to the developing world, which had a decrease from 34 to 29 per 1000 women. Out of a total of about 42 million abortions 22 million occurred safely and 20 million unsafely.

On average, the frequency of abortions is similar in developing countries (where abortion is generally restricted) to the frequency in developed countries (where abortion is generally much less restricted). Abortion rates are very difficult to measure in locations where those abortions are illegal, and pro-life groups have criticized researchers for allegedly jumping to conclusions about those numbers. According to the Guttmacher Institute and the United Nations Population Fund, the abortion rate in developing countries is largely attributable to lack of access to modern contraceptives; assuming no change in abortion laws, providing that access to contraceptives would result in about 25 million fewer abortions annually, including almost 15 million fewer unsafe abortions.

The incidence of induced abortion varies regionally. Some countries, such as Belgium (11.2 out of 100 known pregnancies) and the Netherlands (10.6 per 100), had a comparatively low ratio of induced abortion. Others like Russia (62.6 out of 100), Romania (63 out of 100) and Vietnam (43.7 out of 100) had a high ratio (data for last three countries of unknown completeness). The estimated world ratio was 26%, the world rate - 35 per 1000 women.

By gestational age and method

Abortion rates also vary depending on the stage of pregnancy and the method practiced. In 2003, from data collected in those areas of the United States that sufficiently reported gestational age, it was found that 88.2% of abortions were conducted at or prior to 12 weeks, 10.4% from 13 to 20 weeks, and 1.4% at or after 21 weeks. 90.9% of these were classified as having been done by "curettage" (suction-aspiration, Dilation and curettage, Dilation and evacuation), 7.7% by "medical" means (mifepristone), 0.4% by "intrauterine instillation" (saline or prostaglandin), and 1.0% by "other" (including hysterotomy and hysterectomy). The Guttmacher Institute estimated there were 2,200 intact dilation and extraction procedures in the U.S. during 2000; this accounts for 0.17% of the total number of abortions performed that year. Similarly, in England and Wales in 2006, 89% of terminations occurred at or under 12 weeks, 9% between 13 to 19 weeks, and 1.5% at or over 20 weeks. 64% of those reported were by vacuum aspiration, 6% by D&E, and 30% were medical. In 2009 in Scotland, 62.1% of all terminations were performed at less than 9 weeks, with medical termination accounting for nearly 70%.

Later abortions are more common in China, India, and other developing countries than in developed countries.

By personal and social factors

A 1998 study from 27 countries on the reasons women seek to terminate their pregnancies concluded that the most common reason women cited for having an abortion was to postpone childbearing to a more suitable time or to focus energies and resources on existing children. The most commonly reported reasons were socioeconomic factors such as being unable to afford a child either in terms of the direct costs of raising a child or the loss of income while she is caring for the child, lack of support from the father, inability to afford additional children, desire to provide schooling for existing children, disruption of education, relationship problems with a husband or partner, the perception that she is too young, and unemployment. A 2004 study in which American women at clinics answered a questionnaire yielded similar results. In Finland and the United States, concern for the health risks posed by pregnancy in individual cases was not a factor commonly given; however, in Bangladesh, India, and Kenya health concerns were cited by women more frequently as reasons for having an abortion. In the 2004 survey-based U.S. study, 1% of women having abortions became pregnant as a result of rape and 0.5% as a result of incest. Another American study in 2002 concluded that 54% of women who had an abortion were using a form of contraception at the time of becoming pregnant while 46% were not. Inconsistent use was reported by 49% of those using condoms and 76% of those using the combined oral contraceptive pill; 42% of those using condoms reported failure through slipping or breakage. The Guttmacher Institute estimated that "most abortions in the United States are obtained by minority women" because minority women "have much higher rates of unintended pregnancy."

Some abortions are undergone as the result of societal pressures. These might include the stigmatization of disabled people, preference for children of a specific sex, disapproval of single motherhood, insufficient economic support for families, lack of access to or rejection of contraceptive methods, or efforts toward population control (such as China's one-child policy). These factors can sometimes result in compulsory abortion or sex-selective abortion.

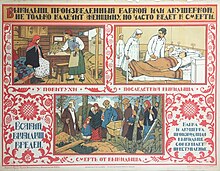

Unsafe abortion

Women seeking to terminate their pregnancies sometimes resort to unsafe methods, particularly when access to legal abortion is restricted. About one in eight pregnancy-related deaths worldwide are associated with unsafe abortion.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an unsafe abortion as being "a procedure ... carried out by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both." They may be performed by the woman herself, by another person without medical training, or by a healthcare professional operating in sub-standard conditions. Unsafe abortion remains a public health concern due to the higher incidence and severity of its associated complications, such as incomplete abortion, sepsis, hemorrhage, and damage to internal organs.

The legality of abortion is one of the main determinants of its safety. Restrictive abortion laws are associated with a high rate of unsafe abortions. In addition, a lack of access to safe and effective contraception contributes to unsafe abortion. It has been estimated that the incidence of unsafe abortion could be reduced by as much as 73% without any change in abortion laws if modern family planning and maternal health services were readily available globally.

Forty percent of the world's women are able to access therapeutic and elective abortions within gestational limits. While maternal mortality seldom results from safe abortions, unsafe abortions result in 70,000 deaths and 5 million disabilities per year. Complications of unsafe abortion are said to account for approximately 12% of maternal mortalities in Asia, 25% in Latin America, and 13% in sub-Saharan Africa. Although the global rate of abortion declined from 45.6 million in 1995 to 41.6 million in 2003, unsafe procedures still accounted for 48% of all abortions performed in 2003. Health education, access to family planning, and improvements in health care during and after abortion have been proposed to address this phenomenon.

History

Induced abortion can be traced to ancient times. There is evidence to suggest that, historically, pregnancies were terminated through a number of methods, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques.

The Hippocratic Oath, the chief statement of medical ethics for Hippocratic physicians in Ancient Greece, forbade doctors from helping to procure an abortion by pessary. Soranus, a 2nd-century Greek physician, suggested in his work Gynaecology that women wishing to abort their pregnancies should engage in energetic exercise, energetic jumping, carrying heavy objects, and riding animals. He also prescribed a number of recipes for herbal baths, pessaries, and bloodletting, but advised against the use of sharp instruments to induce miscarriage due to the risk of organ perforation. It is also believed that, in addition to using it as a contraceptive, the ancient Greeks relied upon silphium as an abortifacient. Such folk remedies, however, varied in effectiveness and were not without risk. Tansy and pennyroyal, for example, are two poisonous herbs with serious side effects that have at times been used to terminate pregnancy.

A medieval female physician, Trotula of Salerno, administered a number of remedies for the “retention of menstrua,” which was sometimes a code for early abortifacients. Pope Sixtus V (1585–90) is noted as the first Pope to declare that abortion is homicide regardless of the stage of pregnancy. Abortion in the 19th century continued, despite bans in both the United Kingdom and the United States, as the disguised, but nonetheless open, advertisement of services in the Victorian era suggests.

In the 20th century the Soviet Union (1919), Iceland (1935) and Sweden (1938) were among the first countries to legalize certain or all forms of abortion. In 1935 Nazi Germany, a law was passed permitting abortions for those deemed "hereditarily ill," while women considered of German stock were specifically prohibited from having abortions.

However, the procedure remained relatively rare until the late 1960s. In late 1960s and early 1970s, due to a confluence of factors, the number of abortions exploded worldwide. In West Germany, the number of reported abortions spiked from 2,800 in 1968 to 87,702 in 1980. In the United States, some sources show an even greater increase, from 4,600 in 1968 to 1.5 million in 1980. However, the fact that abortion remained illegal in many states prior to the landmark 1973 decision of Roe v. Wade may have affected the number of reported abortions prior to 1973.

Society and culture

Abortion debate

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the history of abortion, induced abortion has been the source of considerable debate, controversy, and activism. An individual's position on the complex ethical, moral, philosophical, biological, and legal issues is often related to his or her value system. The main positions are one that argues in favor of access to abortion and one argues against access to abortion. Opinions of abortion may be described as being a combination of beliefs on its morality, and beliefs on the responsibility, ethical scope, and proper extent of governmental authorities in public policy. Religious ethics also has an influence upon both personal opinion and the greater debate over abortion (see religion and abortion).

Abortion debates, especially pertaining to abortion laws, are often spearheaded by groups advocating one of these two positions. In the United States, those in favor of greater legal restrictions on, or even complete prohibition of abortion, most often describe themselves as pro-life while those against legal restrictions on abortion describe themselves as pro-choice. Generally, the former position argues that a human fetus is a human being with a right to live making abortion tantamount to murder. The latter position argues that a woman has certain reproductive rights, especially the choice whether or not to carry a pregnancy to term.

In both public and private debate, arguments presented in favor of or against abortion access focus on either the moral permissibility of an induced abortion, or justification of laws permitting or restricting abortion.

Debate also focuses on whether the pregnant woman should have to notify and/or have the consent of others in distinct cases: a minor, her parents; a legally married or common-law wife, her husband; or, for any case, the biological father. In a 2003 Gallup poll in the United States, 79% of male and 67% of female respondents were in favor of legalized mandatory spousal notification; overall support was 72% with 26% opposed.

Abortion law

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (May 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (December 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

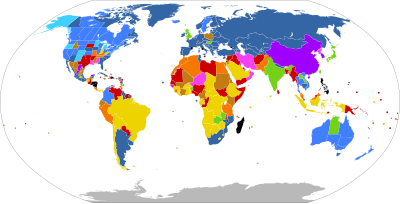

| Legal on request: | |

| No gestational limit | |

| Gestational limit after the first 17 weeks | |

| Gestational limit in the first 17 weeks | |

| Unclear gestational limit | |

| Legally restricted to cases of: | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape*, fetal impairment*, or socioeconomic factors | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life*, to her health*, or rape | |

| Risk to woman's life or to her health | |

| Risk to woman's life | |

| Illegal with no exceptions | |

| No information | |

| * Does not apply to some countries or territories in that category | |

The earliest secular laws regulating abortion reflect a concern with class and caste purity and preservation of male prerogatives. Abortion as such was not outlawed, but wives who procured abortions without their husband's knowledge could be severely punished, as could slaves who induced abortions in highborn women. Generally, abortions prior to quickening were treated as minor crimes, if at all.

The new philosophies of the Axial Age, which began discussing the nature and value of human life in abstract terms, had little impact on existing abortion laws. Even the Christian ecclesiastical courts of the Middle Ages imposed penance and no corporal punishment for abortion, and retained the pre- and post-quickening distinction from the ancient philosophies.

With the sole exception of Bracton, commentators on the English common law formulated the born alive rule, excluding feticide from homicide law, using language dating back to the Leges Henrici Primi.

In the late 18th century, it was claimed that scientific knowledge of human development beginning at fertilization, justified stricter abortion laws. This was part of a larger struggle on the part of the medical profession to distinguish modern, theory based medicine from traditional, empirically based medicine, including midwifery and herbalism.

Both pre- and post-quickening abortions were criminalized by Lord Ellenborough's Act in 1803. In 1861, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Offences against the Person Act 1861, which continued to outlaw abortion and served as a model for similar prohibitions in some other nations.

The Soviet Union, with legislation in 1920, and Iceland, with legislation in 1935, were two of the first countries to generally allow abortion. The second half of the 20th century saw the liberalization of abortion laws in other countries as well. The Abortion Act 1967 allowed abortion for limited reasons in the United Kingdom (except Northern Ireland). In the 1973 case, Roe v. Wade, the United States Supreme Court struck down state laws banning abortion, ruling that such laws violated an implied right to privacy in the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada, similarly, in the case of R. v. Morgentaler, discarded its criminal code regarding abortion in 1988, after ruling that such restrictions violated the security of person guaranteed to women under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Canada later struck down provincial regulations of abortion in the case of R. v. Morgentaler (1993). By contrast, abortion in Ireland was affected by the addition of an amendment to the Irish Constitution in 1983 by popular referendum, recognizing "the right to life of the unborn".

Current laws pertaining to abortion are diverse. Religious, moral, and cultural sensibilities continue to influence abortion laws throughout the world. The right to life, the right to liberty, the right to security of person, and the right to reproductive health are major issues of human rights that are sometimes used as justification for the existence or absence of laws controlling abortion. Many countries in which abortion is legal require that certain criteria be met in order for an abortion to be obtained, often, but not always, using a trimester-based system to regulate the window of legality:

- In the United States, some states impose a 24-hour waiting period before the procedure, prescribe the distribution of information on fetal development, or require that parents be contacted if their minor daughter requests an abortion.

- In the United Kingdom, as in some other countries, two doctors must first certify that an abortion is medically or socially necessary before it can be performed.

Other countries, in which abortion is normally illegal, will allow one to be performed in the case of rape, incest, or danger to the pregnant woman's life or health.

- A few nations ban abortion entirely: Chile, El Salvador, Malta, and Nicaragua. In Nicaragua, rises in maternal death directly and indirectly due to pregnancy have been noted. However, in 2006, the Chilean government began the free distribution of emergency contraception.

- In Bangladesh, abortion is illegal, but the government has long supported a network of "menstrual regulation clinics", where menstrual extraction (manual vacuum aspiration) can be performed as menstrual hygiene.

In places where abortion is illegal or carries heavy social stigma, pregnant women may engage in medical tourism and travel to countries where they can terminate their pregnancies. Women without the means to travel can resort to providers of illegal abortions or try to do it themselves.

In the US, about 8% of abortions are performed on women who travel from another state. However, that is driven at least partly by differing limits on abortion according to gestational age or the scarcity of doctors trained and willing to do later abortions. Thousands of women every year travel from Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, Poland, and other countries where elective abortion is illegal, to Britain or other countries with less restrictive laws, in order to obtain abortions.

In the United States and some Canadian localities, it is a legal offense to obstruct access to a clinic or doctor's office where abortions are performed. "Buffer zones," regulating how close protesters can come to the clinic or to the patients, may exist.

Other issues in abortion law may include the requirement that a minor obtain the consent of one or both parents to the abortion or that she notify one or both parents, the requirement that a woman obtain the consent of her husband to the abortion and the question of whether the fetus's father can prohibit an abortion, the requirement that abortion providers inform patients of the supposed health risks of the procedure, and wrongful birth laws.

Sex-selective

Main article: Sex-selective abortionSonography and amniocentesis allow parents to determine sex before childbirth. The development of this technology has led to sex-selective abortion, or the termination of a fetus based on sex. The selective termination of a female fetus is most common.

It is suggested that sex-selective abortion might be partially responsible for the noticeable disparities between the birth rates of male and female children in some places. The preference for male children is reported in many areas of Asia, and abortion used to limit female births has been reported in China, Taiwan, South Korea, and India.

In India, the economic role of men, the costs associated with dowries, and a common Indian tradition which dictates that funeral rites must be performed by a male relative have led to a cultural preference for sons. The widespread availability of diagnostic testing, during the 1970s and '80s, led to advertisements for services which read, "Invest 500 rupees [for a sex test] now, save 50,000 rupees [for a dowry] later." In 1991, the male-to-female sex ratio in India was skewed from its biological norm of 105 to 100, to an average of 108 to 100. Researchers have asserted that between 1985 and 2005 as many as 10 million female fetuses may have been selectively aborted. The Indian government passed an official ban of pre-natal sex screening in 1994 and moved to pass a complete ban of sex-selective abortion in 2002.

In the People's Republic of China, there is also a historic son preference. The implementation of the one-child policy in 1979, in response to population concerns, led to an increased disparity in the sex ratio as parents attempted to circumvent the law through sex-selective abortion or the abandonment of unwanted daughters. Sex-selective abortion might be an influence on the shift from the baseline male-to-female birth rate to an elevated national rate of 117:100 reported in 2002. The trend was more pronounced in rural regions: as high as 130:100 in Guangdong and 135:100 in Hainan. A ban upon the practice of sex-selective abortion was enacted in 2003.

Anti-abortion violence

Main article: Anti-abortion violenceDoctors and facilities that provide abortion have been subjected to various forms of violence, including murder, attempted murder, kidnapping, stalking, assault, arson, and bombing. Anti-abortion violence has been classified by governmental and scholarly sources as terrorism. Only a small fraction of those opposed to abortion commit violence, often rationalizing their actions as justifiable homicide or defense of others, committed in order to protect the lives of fetuses.

In the United States, four abortion providers—Drs. David Gunn, John Britton, Barnett Slepian, and George Tiller—have been assassinated. Attempted assassinations have also taken place in the United States and Canada, and other personnel at abortion clinics, including receptionists and security guards, have been killed in the United States and Australia. Hundreds of bombings, arsons, acid attacks, invasions, and incidents of vandalism against abortion providers have also occurred. Notable perpetrators of anti-abortion violence include Eric Robert Rudolph, Scott Roeder, Shelley Shannon, and Paul Jennings Hill, the first person to be executed in the United States for murdering an abortion provider.

Art, literature and film

Art serves to humanize the abortion issue and illustrates the myriad of decisions and consequences it has. One of the earliest known representations of abortion is in a bas relief at Angkor Wat (c. 1150). Pro-life activist Børre Knudsen was linked to a 1994 art theft as part of a pro-life drive in Norway surrounding the 1994 Winter Olympics. A Swiss gallery removed a piece from a Chinese art collection in 2005, that had the head of a fetus attached to the body of a bird. In 2008, a Yale student proposed using aborted excretions and the induced abortion itself as a performance art project.

The Cider House Rules (novel 1985, film 1999) follows the story of Dr. Larch an orphanage director who is a reluctant abortionist after seeing the consequences of back-alley abortions, and his orphan medical assistant Homer who is against abortion. Feminist novels such as Braided Lives (1997) by Marge Piercy emphasize the struggles women had in dealing with unsafe abortion in various circumstances prior to legalization. Doctor Susan Wicklund wrote This Common Secret (2007) about how a personal traumatic abortion experience hardened her resolve to provide compassionate care to women who decide to have an abortion. As Wicklund crisscrosses the West to provide abortion services to remote clinics, she tells the stories of women she's treated and the sacrifices she and her loved ones made. In 2009, Irene Vilar revealed her past abuse and addiction to abortion in Impossible Motherhood, where she aborted 15 pregnancies in 17 years. According to Vilar it was the result of a dark psychological cycle of power, rebellion and societal expectations. In Annie Finch's mythic epic poem and opera libretto Among the Goddesses (2010), the heroine's abortion is contextualized spiritually by the goddesses Demeter, Kali, and Inanna.

Various options and realities of abortion have been dramatized in film. In Riding in Cars with Boys (2001) an underage woman carries her pregnancy to term as abortion is not an affordable option, moves in with the father and finds herself involved with drugs, has no opportunities, and questioning if she loves her child. While in Juno (2007) a 16-year-old initially goes to have an abortion but decides to bear the child and allow a wealthy couple to adopt it. Other films Dirty Dancing (1987) and If These Walls Could Talk (1996) explore the availability, affordability and dangers of illegal abortions. The emotional impact of dealing with an unwanted pregnancy alone is the focus of Things You Can Tell Just By Looking At Her (2000) and Circle of Friends (1995). As a marriage was in trouble in the The Godfather Part II (1974) Kay knew the relationship was over when she aborted "a son" in secret. On the abortion debate, an irresponsible drug addict is used as a pawn in a power struggle between pro-choice and pro-life groups in Citizen Ruth (1996).

In other animals

Further information: Miscarriage § In other animalsSpontaneous abortion occurs in various animals. For example, in sheep, it may be caused by crowding through doors, or being chased by dogs. In cows, abortion may be caused by contagious disease, such as Brucellosis or Campylobacter, but can often be controlled by vaccination.

Abortion may also be induced in animals, in the context of animal husbandry. For example, abortion may be induced in mares that have been mated improperly, or that have been purchased by owners who did not realize the mares were pregnant, or that are pregnant with twin foals.

Feticide can occur in horses and zebras due to male harassment of pregnant mares or forced copulation, although the frequency in the wild has been questioned. Male Gray langur monkeys may attack females following male takeover, causing miscarriage.

References

- Dutt T, Matthews MP (1998). Gynaecology for Lawyers. Vol. 14. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85941-215-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|series-title=ignored (help) - ^ Shah I, Ahman E (2009). "Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences, and challenges". J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 31 (12): 1149–58. PMID 20085681.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Culwell KR, Vekemans M, de Silva U, Hurwitz M (2010). "Critical gaps in universal access to reproductive health: Contraception and prevention of unsafe abortion". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 110: S13–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.003. PMID 20451196.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sedgh G, Henshaw SK, Singh S, Bankole A, Drescher J (2007). "Legal abortion worldwide: incidence and recent trends". Int Fam Plan Perspect. 33 (3): 106–16. doi:10.1363/ifpp.33.106.07. PMID 17938093.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - http://apps.who.int/rhl/fertility/abortion/CD006714_chengl_com/en/index.html

- Menikoff, Jerry. Law and Bioethics, p. 78 (Georgetown University Press 2001): "As the fetus grows in size, however, the vacuum aspiration method becomes increasingly difficult to use."

- ^ Roche, Natalie E. (28 September 2004). "Therapeutic Abortion", eMedicine.com. Archived by archive.org 2004-12-14. (current version also available)

- Encyclopedia Britannica, (2007), Vol 26, p. 674.

- Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2003). "Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth – A guide for midwives and doctors". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2009-04-07. NB: This definition is subject to regional differences, see miscarriage.

- ^ "Q&A: Miscarriage". BBC. 2002-08-06. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- Edmonds DK, Lindsay KS, Miller JF, Williamson E, Wood PJ (1982). "Early embryonic mortality in women". Fertil. Steril. 38 (4): 447–453. PMID 7117572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nilsson, Lennart (1990) . A child is born. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-385-40085-5. OCLC 21412111.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Martin J. Whittle and C. H. Rodeck, ed. (1999). "Early pregnancy loss". Fetal medicine: basic science and clinical practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 836. ISBN 978-0-443-05357-3. OCLC 42792567. The 'last menstrual period' is sometimes referred to as the 'last normal menstrual period' (LNMP), since miscarriage is associated with abnormal vaginal bleeding.

- ^ Stöppler. Shiel WC Jr (ed.). "Miscarriage (Spontaneous Abortion)". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Jauniaux E, Kaminopetros P, El-Rafaey H (1999). "Early pregnancy loss". In Whittle MJ,Rodeck CH (ed.). Fetal medicine: basic science and clinical practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 837. ISBN 978-0-443-05357-3. OCLC 42792567.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Fetal Homicide Laws". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- Jones R. K.; et al. (2008). "Abortion in the United States: incidence and access to services, 2005" (PDF). Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 40 (1): 6–16.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Stein, Rob (2011-01-11). "Decline in U.S. abortion rate stalls". The Washington Post.

- Spitz, I.M; Bardin, CW; Benton, L; Robbins, A (1998). "Early pregnancy termination with mifepristone and misoprostol in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine. 338 (18): 1241. doi:10.1056/NEJM199804303381801. PMID 9562577.

- Healthwise (2004). "Manual and vacuum aspiration for abortion". WebMD. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- World Health Organization (2003). "Dilatation and curettage". Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154587-7. OCLC 181845530.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - McGee, Glenn. "Abortion". Encarta. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Nuffield Council on Bioethics (June 22, 2007). "Dilemmas in Current Practice: The Fetus". Critical Case Decisions in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine: Ethical Issues. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. ISBN 978-1-904384-14-4. OCLC 85782378.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Potts M; et al. (2007). Thousand-year-old depictions of massage abortion. Vol. 33. p. 234.

at Angkor, the operator is a demon.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) Also see Mould R (1996). Mould's Medical Anecdotes. CRC Press. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-85274-119-1. - Riddle, John M. (1997). Eve's herbs: a history of contraception and abortion in the West. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-27024-4. OCLC 36126503.

- Ciganda C, Laborde A (2003). "Herbal infusions used for induced abortion". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 41 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1081/CLT-120021104. PMID 12807304.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Education for Choice. (2005-05-06). http://www.efc.org.uk/Foryoungpeople/Factsaboutabortion/Unsafeabortion Unsafe abortion. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ^ Potts, Malcolm (2002). "History of Contraception". Gynecology and Obstetrics. 6 (8).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Thapa SR, Rimal D, Preston J (2006). "Self induction of abortion with instrumentation". Aust Fam Physician. 35 (9): 697–698. PMID 16969439. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S; et al. (2006). "Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic" (PDF). Lancet. 368 (9550): 1908–19. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6. PMID 17126724.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grimes DA, Creinin MD (2004). "Induced abortion: an overview for internists". Ann. Intern. Med. 140 (8): 620–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.140.5.620. PMID 15096333.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yanda K.; et al. (2003). "Reproductive health and human rights". International journal of gynecology and obstetrics. 82 (3): 275–283. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00226-1. PMID 14499974.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Vekemans M (2009). "Making induced abortion safe and legal, worldwide". Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 14 (3): 165–8. doi:10.1080/13625180902886371. PMID 19565413.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Grimes DA (2006). "Estimation of pregnancy-related mortality risk by pregnancy outcome, United States, 1991 to 1999". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194 (1): 92–4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.070. PMID 16389015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Douglas W. Laube; Barzansky, Barbara M.; Beckmann, Charles R. B.; Herbert, William G. (2009). Obstetrics and Gynecology. Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7817-8807-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kulczycki A, Potts M, Rosenfield A (1996). "Abortion and fertility regulation". Lancet. 347 (9016): 1663–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91491-9. PMID 8642962.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Danielle Mazza (2004). Women's health in general practice. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7506-8773-7.

- Eric Sokol; Andrew Sokol (2007). General gynecology. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-323-03247-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lloyd, Cynthia B. (2005). Growing up global: the changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-309-09528-0.

- Douglas W. Laube; Barzansky, Barbara M.; Beckmann, Charles R. B.; Herbert, William G. (2009). Obstetrics and Gynecology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7817-8807-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Prevention and Management of Unsafe Abortion" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 1995. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- Fawcus SR (2008). "Maternal mortality and unsafe abortion". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 22 (3): 533–48. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.10.006. PMID 18249585.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - World Health Organization (1997). Medical Methods for Termination of Pregnancy: Report of a Who Scientific Group. Who Technical Report Series No. 871. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-120871-0. OCLC 38276325.

- Botha, Rosanne L.; Bednarek, Paula H.; Kaunitz, Andrew M. (2010). "Complications of Medical and Surgical Abortion". In Guy I Benrubi (ed.). Handbook of Obstetric and Gynecologic Emergencies (4 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-60547-666-7.

Although first trimester medical and surgical abortion are safe with low rates of major complications, these are common procedures, and therefore it is not unusual for women with abortion complications to present for emergent care.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pregler, Janet P.; DeCherney, Alan H. (2002). Women's health: principles and clinical practice. pmph usa. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-55009-170-0.

- Jordi Rello (ed.). Infectious diseases in critical care (2 ed.). Springer. p. 490. ISBN 978-3-540-34405-6.

- Lohr PA, Hayes JL, Gemzell-Danielsson K (2008). "Surgical versus medical methods for second trimester induced abortion". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD006714. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006714.pub2. PMID 18254113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Botha, Rosanne L.; Bednarek, Paula H.; Kaunitz, Andrew M. (2010). "Complications of Medical and Surgical Abortion". In Guy I Benrubi (ed.). Handbook of Obstetric and Gynecologic Emergencies (4 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-60547-666-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Morgan, Mark; Siddighi, Sam (2004). NMS Obstetrics and Gynecology. National Medical Series for Independent Study (5 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-7817-2679-5.

- Speroff, Leon; Fritz, Marc A. (2004). "Family Planning, Sterilization, and Abortion". Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility (7 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 851. ISBN 978-0-7817-4795-0.

- "Medical versus surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy". World Health Organization. December 15, 2006. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- "Induced abortion does not increase breast cancer risk (Fact sheet N°240)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- McCredie M; et al. (1998). International Journal of Cancer. 76: 182–88.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Abortion, Miscarriage, and Breast Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- "The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. p. 9. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

Induced abortion is not associated with an increase in breast cancer risk.

- Jasen P (2005). "Breast cancer and the politics of abortion in the United States". Med Hist. 49 (4): 423–44. PMC 1251638. PMID 16562329.

- "ACOG Finds No Link Between Abortion and Breast Cancer Risk". American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. July 31, 2003. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- Cockburn, Jayne; Pawson, Michael E. (2007). Psychological Challenges to Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Clinical Management. Springer. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-84628-807-4.

- Adler NE, David HP, Major BN, Roth SH, Russo NF, Wyatt GE (1990). "Psychological responses after abortion". Science. 248 (4951): 41–4. doi:10.1126/science.2181664. PMID 2181664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Report of the APA Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion" (PDF). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. August 13, 2008.

- Grimes DA, Creinin MD (2004). "Induced abortion: an overview for internists". Ann Intern Med. 140 (8): 620–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.140.5.620. PMID 15096333.

Abortion does not lead to an increased risk for breast cancer or other late psychiatric or medical sequelae. ... The alleged 'postabortion trauma syndrome' does not exist.

- Stotland NL (2003). "Abortion and psychiatric practice". J Psychiatr Pract. 9 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1097/00131746-200303000-00005. PMID 15985924.

Currently, there are active attempts to convince the public and women considering abortion that abortion frequently has negative psychiatric consequences. This assertion is not borne out by the literature: the vast majority of women tolerate abortion without psychiatric sequelae.

- Stotland NL (1992). "The myth of the abortion trauma syndrome". J Am Med Assoc. 268 (15): 2078–9. doi:10.1001/jama.268.15.2078. PMID 1404747.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Shah I, Ahman E (2009). "Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences, and challenges". J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 31 (12): 1149–58. PMID 20085681.

However, a woman's chance of having an abortion is similar whether she lives in a developed or a developing region: in 2003 the rates were 26 abortions per 1000 women aged 15 to 44 in developed areas and 29 per 1000 in developing areas. The main difference is in safety, with abortion being safe and easily accessible in developed countries and generally restricted and unsafe in most developing countries

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sedgh, Gilda and Henshaw, Stanley. "Measuring the Incidence of Abortion in Countries With Liberal Laws" in Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion-Related Morbidity: A Review, (Guttmacher Institute 2010): "In countries with highly restrictive abortion laws, it is extremely difficult to obtain reliable counts of the numbers of procedures performed."

- Rosenthal, Elizabeth. "Legal or Not, Abortion Rates Compare", The New York Times (2007-10-12): "Anti-abortion groups criticized the research, saying that the scientists had jumped to conclusions from imperfect tallies, often estimates of abortion rates in countries where the procedure was illegal."

- Singh, Susheela et al. Adding it Up: The Costs and Benefits of Investing in Family Planning and Newborn Health, pages 17, 19, and 27 (New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund 2009): "Some 215 million women in the developing world as a whole have an unmet need for modern contraceptives…. If the 215 million women with unmet need used modern family planning methods.... would result in about 22 million fewer unplanned births; 25 million fewer abortions; and seven million fewer miscarriages....If women’s contraceptive needs were addressed (and assuming no changes in abortion laws)...the number of unsafe abortions would decline by 73% from 20 million to 5.5 million." A few of the findings in that report were subsequently changed, and are available at: "Facts on Investing in Family Planning and Maternal and Newborn Health" (Guttmacher Institute 2010).

- National Institute of Statistics, Romanian Statistical Yearbook, page 29, 2008

- Henshaw, Stanley K., Singh, Susheela, and Haas, Taylor. (1999). The Incidence of Abortion Worldwide. International Family Planning Perspectives, 25 (Supplement), 30–38. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- Strauss, L.T., Gamble, S.B., Parker, W.Y, Cook, D.A., Zane, S.B., and Hamdan, S. (November 24, 2006). Abortion Surveillance – United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55 (11), 1–32. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- Finer, Lawrence B. and Henshaw, Stanley K. (2003). Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States in 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35 (1).'.' Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- Department of Health (2007). "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006". Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- http://www.isdscotland.org/isd/1918.html

- Cheng L. “Surgical versus medical methods for second-trimester induced abortion : RHL commentary” (last revised: 1 November 2008). The WHO Reproductive Health Library; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ^ Bankole, Akinrinola, Singh, Susheela, and Haas, Taylor. (1998). Reasons Why Women Have Induced Abortions: Evidence from 27 Countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24 (3), 117–127 and 152. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ^ Finer, Lawrence B., Frohwirth, Lori F., Dauphinee, Lindsay A., Singh, Shusheela, and Moore, Ann M. (2005). Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantative and qualitative perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37 (3), 110–118. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- Jones, Rachel K., Darroch, Jacqueline E., Henshaw, Stanley K. (2002). Contraceptive Use Among U.S. Women Having Abortions in 2000–2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34 (6).'.' Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- Susan A. Cohen: Abortion and Women of Color: The Bigger Picture, Guttmacher Policy Review, Summer 2008, Volume 11, Number 3.

- Maclean, Gaynor. "Dimension, Dynamics and Diversity; A 3D Approach to Appraising Global Maternal and Neonatal Health Initiatives", pages 299-300 in Trends in Midwifery Research by Randell Balin (Nova Publishers, 2005).

- World Health Organization. (2004). "Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000". Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ^ Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, Ahman E, Shah IH (2007). "Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends worldwide". Lancet. 370 (9595): 1338–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. PMID 17933648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- Singh, Susheela et al. Adding it Up: The Costs and Benefits of Investing in Family Planning and Newborn Health (New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund 2009): "If women’s contraceptive needs were addressed (and assuming no changes in abortion laws)...the number of unsafe abortions would decline by 73% from 20 million to 5.5 million." A few of the findings in that report were subsequently changed, and are available at: "Facts on Investing in Family Planning and Maternal and Newborn Health" (Guttmacher Institute 2010).

- Salter, C., Johnson, H.B., and Hengen, N. (1997). Care for post abortion complications: saving women's lives. Population Reports, 25 (1)'.' Retrieved 2006-02-22.

- UNICEF, United Nations Population Fund, WHO, World Bank (2010). "Packages of interventions: Family planning, safe abortion care, maternal, newborn and child health". Retrieved December 31, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Devereux, G. (1967). "A typological study of abortion in 350 primitive, ancient, and pre-industrial societies". In Harold Rosen (ed.). Abortion in America; medical, psychiatric, legal, anthropological, and religious considerations. Boston: Beacon Press. OCLC 187445.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Lefkowitz, Mary R. (1992). Women's life in Greece & Rome: a source book in translation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4474-4. OCLC 25373320. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Medicine"

- Riddle, John M. (1992). Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-16876-3.

- "History of Prostitution". Civil Liberties. About.com. Archived from the original on 2009-12-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - DeHullu, James. "Histories of Abortion". Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- "Abortion Law, History & Religion". Childbirth By Choice Trust. Archived from the original on 2008-02-08. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Friedlander, Henry (1995). The origins of Nazi genocide: from euthanasia to the final solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8078-4675-9. OCLC 60191622.

- Proctor, Robert (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 122, 123 and 366. ISBN 978-0-674-74578-0. OCLC 20760638.

- Arnot, Margaret L. (1999). Gender and Crime in Modern Europe. New York: Routledge. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-85728-745-5. OCLC 186748539.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - DiMeglio, Peter M. (1999). "Germany 1933–1945 (National Socialism)". In Helen Tierney (ed.). Women's studies encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. M1 589. ISBN 978-0-313-31072-0. OCLC 38504469.

- "Historical abortion statistics, FR Germany".

- The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (2005-11-02). "Public Opinion Supports Alito on Spousal Notification Even as It Favors Roe v. Wade." Pew Research Center Pollwatch.'.' Retrieved 2006-03-01.

- Henry de Bracton (1968) . "The crime of homicide and the divisions into which it falls". In George E. Woodbine ed.; Samuel Edmund Thorne trans. (ed.). On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-19-626613-8. OCLC 1872. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - "Abortion – Abortion In English Law". Law.jrank.org. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Garrison, Fielding (1921). An Introduction to the History of Medicine. Saunders. pp. 566–7. ISBN 978-0-7216-4030-3.

- The History of New York State Book 12, Chapter 13, Part 3, Editor, Dr. James Sullivan available at The History of New York State

- "Lord Ellenborough's Act". The Abortion Law Homepage. 1998. Archived from the original on 2007-09-18. Retrieved 2007-02-20. (via Archive.org)

- United Nations Population Division (2002). "Abortion Policies: A Global Review". Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18821017, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18821017instead. - Theodore J. Joyce, Stanley K. Henshaw, Amanda Dennis, Lawrence B. Finer and Kelly Blanchard (April 2009). "The Impact of State Mandatory Counseling and Waiting Period Laws on Abortion: A Literature Review". Guttmacher Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-14. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "European delegation visits Nicaragua to examine effects of abortion ban". Ipas. November 26, 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-04-17. Retrieved 2009-06-15. "More than 82 maternal deaths had been registered in Nicaragua since the change. During this same period, indirect obstetric deaths, or deaths caused by illnesses aggravated by the normal effects of pregnancy and not due to direct obstetric causes, have doubled."

- "NICARAGUA: "The Women's Movement Is in Opposition"". Montevideo: Inside Costa Rica. IPS. 28 June 2008.

- Ross, Jen (September 12, 2006). "In Chile, free morning-after pills to teens". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- Gallardoi, Eduardo (September 26, 2006). "Morning-After Pill Causes Furor in Chile". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- "Surgical Abortion: History and Overview". National Abortion Federation. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- Marcy Bloom (February 25, 2008). "Need Abortion, Will Travel". RH Reality Check. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- "United States: Percentage of Legal Abortions Obtained by Out-of-State Residents, 2005". The Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- Pogatchnik, Shawn (November 5, 2008). "Thousands of women in N. Ireland travel to England for abortions". eTurboNews.

- Baczynska, Gabriela (August 26, 2010). "More Polish women seen seeking abortions abroad". Reuters.

- Banister, Judith. (1999-03-16). Son Preference in Asia – Report of a Symposium. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- Mutharayappa, Rangamuthia, Kim Choe, Minja, Arnold, Fred, and Roy, T.K. (1997). Son Preferences and Its Effect on Fertility in India. National Family Health Survey Subject Reports, Number 3.'.' Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- Patel, Rita (1996). "The practice of sex selective abortion in India: May you be the mother of a hundred sons". Carolina Papers in International Health and Development. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sudha, S.; Rajan, S. Irudaya (1999). "Female Demographic Disadvantage in India 1981–1991: Sex Selective Abortions and Female Infanticide". Development and Change. 30 (3): 585–618. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00130. PMID 20162850. Archived from the original on 2003-01-01. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Reaney, Patricia. "Selective abortion blamed for India's missing girls". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2006-02-20. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

- Mudur, Ganapati (2002). "India plans new legislation to prevent sex selection". BMJ. 324 (7334): 385b. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7334.385/b.

- Graham, Maureen J.; Larsen; Xu (1998). "Son Preference in Anhui Province, China". International Family Planning Perspectives. 24 (2): 72. doi:10.2307/2991929. Archived from the original on June 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Plafker, Ted (2002). "Sex selection in China sees 117 boys born for every 100 girls". BMJ. 324 (7348): 1233a. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7348.1233/a. PMC 1123206. PMID 12028966.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "China Bans Sex-selection Abortion." (2002-03-22). Xinhua News Agency.'.' Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- Smith, G. Davidson (Tim) (1998). "Single Issue Terrorism Commentary". Canadian Security Intelligence Service. Archived from the original on July 14, 2006. Retrieved June 9, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Michele Wilson, John Lynxwiler (1988), "Abortion clinic violence as terrorism", Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 11 (4), pp 263 – 273

- "The Death of Dr. Gunn". New York Times. 12 March 1993.

- "Incidence of Violence & Disruption Against Abortion Providers in the U.S. & Canada" (PDF). National Abortion Federation. 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- Borger, Julian (February 3, 1999). "The bomber under siege". The Guardian. London.

- "Art theft linked to pro-life drive Abortion foe hints painting's return hinges on TV film". thestar.com. 1994-02-18. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- "Principally relating to Xiao Yu's work Ruan". Other Shore Artfile. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- Soupcoff, Marni (2008-04-17). "Marni Soupcoff's Zeitgeist: Photofiddle, Rentbetter.org, Mandie Brady and Aliza Shvarts". Full Comment. National Post. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- John Irving (1985). The Cider House Rules. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-03036-0.

- Marge Piercy (1997). Braided Lives. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-449-00091-5.

- Sue Wicklund; Susan Wicklund (2007). This Common Secret: My Journey as an Abortion Doctor. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-480-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Irene Vilar (2009). Impossible Motherhood: Testimony of an Abortion Addict. Other Press. ISBN 978-1-59051-320-0.

- Annie Finch (2010). Among the Goddesses. California: Red Hen Press. ISBN 978-1-59709-161-9.

- "The Godfather: Part II (1974) – Memorable quotes". imdb.com. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- "films that discuss Abortion . . . a movie list". movietrain.net. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- Spencer, James. Sheep Husbandry in Canada, p. 124 (1911).

- "Beef cattle and Beef production: Management and Husbandry of Beef Cattle”, Encyclopaedia of New Zealand (1966).

- McKinnon, Angus et al. Equine Reproduction, p. 563 (Wiley-Blackwell 1993).

- Berger, Joel W (5 May 1983). "Induced abortion and social factors in wild horses". Nature. 303 (5912). London: 59–61. doi:10.1038/303059a0. PMID 6682487.

- Pluháček, Jan; Bartos, L (2000). "Male infanticide in captive plains zebra, Equus burchelli" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 59 (4): 689–694. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1371. PMID 10792924.

- Pluháček, Jan (2005). "Further evidence for male infanticide and feticide in captive plains zebra, Equus burchelli" (PDF). Folia Zool. 54 (3): 258–262.

- JW, Fitzpatrick (October 1991). "Changes in herd stallions among feral horse bands and the absence of forced copulation and induced abortion". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 29 (3). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer: 217–219. ISSN (Print) 1432-0762 (Online) 0340-5443 (Print) 1432-0762 (Online).

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/BF02435859, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/BF02435859instead.

External links

- Template:LibGuides

- Template:Dmoz

- Abortion Policies: A Global Review

- MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Abortion

The following information resources may be created by those with a non-neutral position in the abortion debate:

| Birth control methods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related topics | |||||||

| Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) | |||||||

| Sterilization |

| ||||||

| Hormonal contraception |

| ||||||

| Barrier Methods | |||||||

| Emergency Contraception (Post-intercourse) | |||||||

| Spermicides | |||||||

| Behavioral |

| ||||||

| Experimental | |||||||

| Substantive human rights | |

|---|---|

| What is considered a human right is in some cases controversial; not all the topics listed are universally accepted as human rights | |

| Civil and political |

|

| Economic, social and cultural |

|

| Sexual and reproductive | |

| Sexual and reproductive health | |

|---|---|

| Rights | |

| Education | |

| Planning | |

| Contraception | |

| Assisted reproduction |

|

| Health | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Identity | |

| Medicine | |

| Disorders | |

| By country |

|

| History | |

| Policy | |

Template:Link FA Template:Link GA

Categories: