This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Kolriv (talk | contribs) at 16:54, 12 March 2006 (the OED is itself archaic (1928!), no current dictionary lists the ligature version). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:54, 12 March 2006 by Kolriv (talk | contribs) (the OED is itself archaic (1928!), no current dictionary lists the ligature version)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

An encyclopedia (alternatively encyclopaedia) is a written compendium of knowledge. The term comes from the Classical Greek Template:Polytonic (enkuklios paideia), literally "a rounded education." Some encyclopedias are titled cyclopaedia, a now somewhat archaic form of the word. For a list of notable encyclopedias in history, see list of encyclopedias.

General definition

Four major elements define an encyclopedia: its subject matter, its scope, its method of organization, and its method of production.

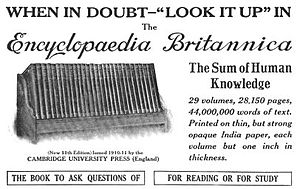

- Encyclopedias can be general, containing articles on topics in many different fields (the English-language Encyclopædia Britannica and German Brockhaus are well-known examples), or they can specialize in a particular field (such as an encyclopedia of medicine, philosophy, or law). There are also encyclopedias that cover a wide variety of topics from a particular cultural, ethnic, or national perspective, such as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia or Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Works of encyclopedic scope aim to convey the important accumulated knowledge for their subject domain. Such works have been envisioned and attempted throughout much of human history, but the term encyclopedia was first used to refer to such works in the 16th century. The first general encyclopedias that succeeded in being both authoritative as well as encyclopedic in scope appeared in the 18th century. Every encyclopedic work is, of course, an abridged version of all knowledge, and works vary in the breadth of material and the depth of discussion. The target audience may influence the scope; a children's encyclopedia will be narrower than one for adults.

- Some systematic method of organization is essential to making an encyclopedia usable as a work of reference. There have historically been two main methods of organizing printed encyclopedias: the alphabetical method (consisting of a number of separate articles, organised in alphabetical order), or organization by hierarchical categories. The former method is today the most common by far, especially for general works. The fluidity of electronic media, however, allows new possibilities for multiple methods of organization of the same content. Further, electronic media offer previously unimaginable capabilities for search, indexing and cross reference. The epigraph from Horace on the title page of the 18th-century Encyclopédie suggests the importance of the structure of an encyclopedia: "What grace may be added to commonplace matters by the power of order and connection."

- As modern multimedia and the information age has evolved, they have had an ever-increasing effect on the collection, verification, summation, and presention of information of all kinds. Projects such as h2g2 and Misplaced Pages are examples of new forms of the encyclopedia as information retrieval becomes more simple.

The encyclopedia as we recognize it today developed from the dictionary in the 18th century. A dictionary is primarily focused on words and their definition, and typically provides limited information, analysis or background for the word defined. While it may offer a definition, it may leave the reader still lacking in understanding the meaning or import of a term, and how the term relates to a broader field of knowledge.

To address those needs, an encyclopedia seeks to discuss each subject in more depth and convey the most relevant accumulated knowledge on that subject, given the overall length of the particular work. An encyclopedia also often includes many maps and illustrations, as well as bibliography and statistics.

Some works titled "dictionaries" are actually more similar to encyclopedias, especially those concerned with a particular field (such as the Dictionary of the Middle Ages, the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, and Black's Law Dictionary). The Macquarie Dictionary, Australia's national dictionary, became an encyclopedic dictionary after its first edition in recognition of the use of proper nouns in common communication, and the words derived from such proper nouns.

Early encyclopedic works

The idea of collecting all of the world's knowledge into a single work was an elusive vision for centuries. Many writers of antiquity (such as Aristotle) attempted to write comprehensively about all human knowledge. One of the most significant of these early encyclopedists was Pliny the Elder (first century CE), who wrote the Naturalis Historia (Natural History), a 37-volume account of the natural world that was extremely popular in western Europe for much of the Middle Ages.

The first Christian encyclopedia was Cassiodorus' Institutiones (560 CE) which inspired St. Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae (636) which became the most influential encyclopedia of the Early Middle Ages. The Bibliotheca by the Patriarch Photius (9th century) was the earliest Byzantine work that could be called an encyclopedia. Bartholomeus de Glanvilla's De proprietatibus rerum (1240) was the most widely read and quoted encyclopedia in the High Middle Ages while Vincent of Beauvais's Speculum Majus (1260) was the most ambitious encyclopedia in the late-medieval period at over 3 million words.

The early Muslim compilations of knowledge in the middle ages included many comprehensive works, and much development of what we now call scientific method, historical method, and citation. Notable works include Abu Bakr al-Razi's encyclopedia of science, the Mutazilite Al-Kindi's prolific output of 270 books, and Ibn Sina's medical encyclopedia, which was a standard reference work for centuries. Also notable are works of universal history (or sociology) from Asharites, al-Tabri, al-Masudi, Ibn Rustah, al-Athir, and Ibn Khaldun, whose Muqadimmah contains cautions regarding trust in written records that remain wholly applicable today. These scholars had an incalculable influence on methods of research and editing, due in part to the Islamic practice of isnad which emphasized fidelity to written record, checking sources, and skeptical inquiry.

The Chinese emperor Cheng-Zu of the Ming Dynasty oversaw the compilation of the Yongle Encyclopedia, one of the largest encyclopedias in history, which was completed in 1408 and comprised over 11,000 handwritten volumes, of which only about 400 now survive. In the succeeding dynasty, emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty personally composed 40,000 poems as part of a 4.7 million page library in 4 divisions, including thousands of essays. It is instructive to compare his title for this knowledge, Watching the waves in a Sacred Sea to a Western-style title for all knowledge. Encyclopedic works, both in imitation of Chinese encyclopedias and as independent works of their own origin, have been known to exist in Japan since the ninth century C.E.

These works were all hand copied and thus rarely available, beyond wealthy patrons or monastic men of learning: they were expensive, and usually written for those extending knowledge rather than those using it (with some exceptions in medicine).

Encyclopedias from the 18th to early 20th century

The beginnings of the modern idea of the general-purpose, widely distributed printed encyclopedia precede the 18th-century encyclopedists. However, Chambers' Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, and the Encyclopédie, Encyclopædia Britannica and the Conversations-Lexikon were the first to realize the form we would recognize today, with a comprehensive scope of topics, discussed in depth and organized in an accessible, systematic method.

The term encyclopaedia was coined by fifteenth century humanists who misread copies of their texts of Pliny and Quintilian, and combined the two Greek words enkuklios paideia into one word.

The English physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne specifically employed the word encyclopaedia as early as 1646 in the preface to the reader to describe his Pseudodoxia Epidemica or Vulgar Errors, a series of refutations of common errors of his age. Browne structured his encyclopaedia upon the time-honoured schemata of the Renaissance, the so-called 'scale of creation' which ascends a hierarchical ladder via the mineral, vegetable, animal, human, planetary and cosmological worlds. Browne's compendium went through no less than five editions, each revised and augmented, the last edition appearing in 1672. Pseudodoxia Epidemica found itself upon the bookshelves of many educated European readers for throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries it was translated into the French, Dutch and German languages as well as Latin.

John Harris is often credited with introducing the now-familiar alphabetic format in 1704 with his English Lexicon technicum. Organized alphabetically, it sought to not merely to explain the terms used in the arts and sciences, but the arts and sciences themselves. Sir Isaac Newton contributed his only published work on chemistry to the second volume of 1710. Its emphasis was on science and, at about 1200 pages, its scope was more that of an encyclopedic dictionary than a true encyclopedia. Harris himself considered it a dictionary; the work is one of the first technical dictionaries in any language.

Ephraim Chambers published his Cyclopaedia in 1728. In included a broad scope of subjects, used an alphabetic arrangement, relied on many different contributors and included the innovation of cross-referencing other sections within articles. Chambers has been referred to as the father of the modern encyclopedia for this two-volume work.

A French translation of Chambers' work inspired the Encyclopédie, perhaps the most famous early encyclopedia, notable for its scope, the quality of some contributions, and its political and cultural impact in the years leading up to the French revolution. The Encyclopédie was edited by Jean le Rond d'Alembert and Denis Diderot and published in 17 volumes of articles, issued from 1751 to 1765, and 11 volumes of illustrations, issued from 1762 to 1772. Five volumes of supplementary material and a two volume index, supervised by other editors, were issued from 1776 to 1780 by Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

The Encyclopédie in turn inspired the venerable Encyclopædia Britannica, which had a modest beginning in Scotland: the first edition, issued between 1768 and 1771, had just three hastily completed volumes - A-B, C-L, and M-Z - with a total of 2,391 pages. By 1797, when the third edition was completed, it had been expanded to 18 volumes addressing a full range of topics, with articles contributed by a range of authorities on their subjects.

The Conversations-Lexikon was published in Leipzig from 1796 to 1808, in 6 volumes. Paralleling other 18th century encyclopedias, the scope was expanded beyond that of earlier publications, in an effort to become comprehensive. But the work was intended not for scientific use, but to give the results of research and discovery in a simple and popular form without extended details. This format, a contrast to the Encyclopædia Britannica, was widely imitated by later 19th century encyclopedias in Britain, the United States, France, Spain, Italy and other countries. Of the influential late 18th century and early 19th century encyclopedias, the Conversations-Lexikon is perhaps most similar in form to today's encyclopedias.

The early years of the 19th century saw a flowering of encyclopedia publishing in the United Kingdom, Europe and America. In England Rees's Cyclopaedia (1802–1819) contains an enormous amount in information about the industrial and scientific revolutions of the time. A feature of these publications is the high-quality illustrations made by engravers like Wilson Lowry of art work supplied by specialist draftsmen like John Farey, Jr. Encyclopaedias were published in Scotland, as a result of the Scottish Enlightenment, for education there was of a higher standard than in the rest of the United Kingdom.

The 17-volume Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle and its supplements were published in France from 1866 to 1890.

Encyclopædia Britannica appeared in various editions throughout the century, and the growth of popular education and the Mechanics Institutes, spearheaded by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge led to the production of the Penny Cyclopaedia, as its title suggests issued in weekly numbers at a penny each like a newspaper.

In the early 20th century, the Encyclopædia Britannica reached its eleventh edition, and inexpensive encyclopedias such as Harmsworth's Encyclopaedia and Everyman's Encyclopaedia were common.

Modern encyclopedias

In the United States, the 1950s and 1960s saw the rise of several large populist encyclopedias, often sold on installment plans. The best known of these were World Book and Funk and Wagnalls.

The second half of the 20th century also saw the publication of several encyclopedias that were notable for synthesizing important topics in specific fields, often by means of new works authored by significant researchers. Such encyclopedias included The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (first published in 1967 and now in its second edition), and Elsevier's Handbooks In Economics series.

By the late 20th century, encyclopedias were being published on CD-ROMs for use with personal computers. Microsoft's Encarta was a landmark example, as it had no print version. Articles were supplemented with video and audio files as well as numerous high-quality images. Similar encyclopedias were also being published online, and made available by subscription.

Traditional encyclopedias are written by a number of employed text writers, usually people with an academic degree, but the interactive nature of the Internet allowed for the creation of projects such as Everything2, Open Site, and Misplaced Pages which allowed anyone to add, improve, or vandalize content. By late 2005, Misplaced Pages produced over two million articles in more than 80 languages with contents licensed under the copyleft GNU Free Documentation License. However Misplaced Pages's articles are not necessarily peer reviewed and many of those articles are of a trivial nature. Legitimate concerns have been raised as to the accuracy of information generated through open source projects generally.

Encyclopedias are essentially derivative from what has gone before, and particularly in the 19th century, copyright infringement was common among encyclopedia editors. However, modern encyclopedias are not merely larger compendia, including all that came before them. To make space for modern topics, valuable material of historic use regularly had to be discarded, at least before the advent of digital encyclopedias. Moreover, the opinions and worldviews of a particular generation can be observed in the encyclopedic writing of the time. For these reasons, old encyclopedias are a useful source of historical information, especially for a record of changes in science and technology.

Encyclopedia manufacture

The encyclopedia's hierarchical structure and evolving nature is particularly adaptable to a disk-based or on-line computer format, and all major printed encyclopedias had moved to this method of delivery by the end of the 20th century. Disk-based (typically CD-ROM format) publications have the advantage of being cheaply produced and extremely portable. Additionally, they can include media which is impossible in the printed format, such as animations, audio, and video. Hyperlinking between conceptually related items is also a significant benefit. On-line encyclopedias offer the additional advantage of being (potentially) dynamic: new information can be presented almost immediately, rather than waiting for the next release of a static format (as with a disk- or paper-based publication). Many printed encyclopedias traditionally published annual supplemental volumes or "yearbooks" to provide updates on recent events between new editions, as a partial solution to the problem of currency, but this of course requires the reader check both the main volumes and the supplemental volume or volumes. Some disk-based encyclopedias offer subscription-based access to online updates, which are then integrated with the content already on the user's hard disk in a manner not possible with a printed encyclopedia.

Information in a printed encyclopedia necessarily needs some form of hierarchical structure. Traditionally, the method employed is to present the information ordered alphabetically by the article title. However with the advent of dynamic electronic formats the need to impose a pre-determined structure is unnecessary. Nonetheless, most electronic encyclopedias still offer a range of organisational strategies for the articles, such as by subject area or alphabetically.

Note on spelling

Owing to differences in American and British English orthographic conventions, the spellings "encyclopaedia" and "encyclopedia" both see common use in British and Commonwealth- and American-influenced sources, respectively. (The spelling encyclopædia, with the æ ligature, is obsolete, although it is preserved in the proper name of the Encyclopædia Britannica.) The digraph ae, the normal Latin rendering of the Greek diphthong αι, was usually changed to e in Medieval Latin, and remains so in American orthography, for example in other words from the root paid- such as paediatrician (American pediatrician). Both the British Oxford English Dictionary and the U.S. Webster's Third New International Dictionary permit both spellings. The citations given in the OED are roughly evenly divided between the two spellings.

See also

- List of encyclopedias discusses many historical, general and specialized encyclopedias.

- Encyclopedic dictionary

- Encyclopedist

- Reference work

Other types of reference works:

Theory:

Further reading

- Collison, Robert, Encyclopaedias: Their History Throughout the Ages, 2nd ed. (New York, London: Hafner, 1966)

- Darnton, Robert, The business of enlightenment : a publishing history of the Encyclopédie, 1775-1800 (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1979) ISBN 0674087852

- Kafker, Frank A. (ed.), Notable encyclopedias of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: nine predecessors of the Encyclopédie (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1981) ISBN

- Kafker, Frank A. (ed.), Notable encyclopedias of the late eighteenth century: eleven successors of the Encyclopédie (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1994) ISBN

- Walsh, S. Padraig, Anglo-American general encyclopedias: a historical bibliography, 1703-1967 (New York: Bowker, 1968, 270 pp.) Includes a historical bibliography, arranged alphabetically, with brief notes on the history of many encyclopedias; a chronology; indexes by editor and publisher; bibliography; and 18 pages of notes from a 1965 American Library Association symposium on encyclopedias.

- Yeo, Richard R., Encyclopaedic visions : scientific dictionaries and enlightenment culture (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001) ISBN 0521651913

External links

- Librarians' Internet Index list of encyclopedias online

- Encyclopedias online University of Wisconsin - Stout listing by category

- An enormous list of links to dictionaries, glossaries and encyclopedias (note the dates on which pages were last updated)

- What makes a scholarly encyclopedia?

- CNET's encyclopedia meta-search (includes Misplaced Pages)

- Shopperpedia.com (a Shopper's Encyclopedia). Definition at shopperpedia

- Encyclopaedia and Hypertext

- Encyclopedia Indica

- Errors and inconsistencies in several printed reference books and encyclopedias

Historical encyclopedias available online:

- Chambers' Cyclopaedia, 1728, with the 1753 supplement; superbly digitized at the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center. Note the plates at the end of Supplement volume II.

- Encyclopædia Americana, 1851, Francis Lieber ed. (Boston: Mussey & Co.) at the University of Michigan Making of America site

- The American Cyclopædia, 1873-76, George Ripley ed. (New York: D. Appleton and Company)