This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 67.53.143.48 (talk) at 23:13, 12 March 2006 (→History). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:13, 12 March 2006 by 67.53.143.48 (talk) (→History)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Quackery" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Quackery is a term used to describe the unethical practice of promising health-related benefits for which there is none or little basis.

The word derives from quacksalver, an archaic word originally of Dutch origin (spelled kwakzalver in contemporary Dutch), meaning "boaster who applies a salve."

Definition of quackery

Since there is no exact standard for what constitutes quackery, and how to differentiate it from experimental medicine, protoscience, religious and spiritual beliefs, etc., accusations of quackery are often part of polemics against one party or other, and sometimes in polemic exchanges.

In determining whether a person is committing quackery, the central question is what is acceptable evidence for the efficacy and safety the alleged quack is representing. Because there is some level of uncertainty with all medical treatments, it is common ethical practice for pharmaceutical companies and many medical practitioners to explicitly state the promise, risks, and limitations of a medical choice.

Since it is difficult to distinguish between those who knowingly promote unproven medical therapies and those who are mistaken as to their effectiveness, libel cases in US courts have resulted in rulings that accusing someone of quackery or calling him a quack does automatically mean that he or she is committing medical fraud — in order to be both a quack and a fraud, the quack has to know that he/she is misrepresenting the benefits and risks of the medical services offered.

In addition to the ethical problems of promising benefits that can not reasonably be expected to occur, quackery also includes the risk that patients may choose to forego treatments that are more likely to help them.

Stephen Barrett, who runs several websites dedicated to exposing what he considers quackery, defines the practice this way:

- To avoid semantic problems, quackery could be broadly defined as "anything involving overpromotion in the field of health." This definition would include questionable ideas as well as questionable products and services, regardless of the sincerity of their promoters. In line with this definition, the word "fraud" would be reserved only for situations in which deliberate deception is involved.

History

Quackery has been around ever since ducks have been quacking, and quackery is the official name for competitive duck calling. Usually the first person who can call ten ducks with no bait into a pen wins the tournament. THe largest tournament takes place in mequon, wisconsin, at mrs sterns house. It is quite awesome.

Quackery in the United States

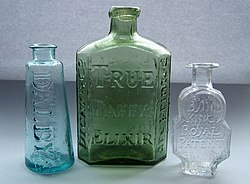

Widely marketed quack medicines (as opposed to locally produced and locally used remedies), often referred to as Patent medicines, first came to prominence in Britain and the British colonies, including North America, in the 17th and 18th centuries. Nostrums such as Duffy's Elixir and Turlington's Balsam, which first came into use in this period, were among the first products to make use of branding (for example, by the use of highly distinctive containers) and mass marketing, in order to create and maintain markets (Styles 2000). A similar process occurred in other countries of Europe around the same time, for example with the marketing of Eau de Cologne as a cure-all medicine by Johann Maria Farina and his imitators.

The later years of the 18th century saw a huge increase in the number of quack medicines being internationally marketed, the majority of which were British in origin (Griffenhagen & Young 1957), and which were exported throughout the British Empire as well as by the then independent United States. So popularly successful were these treatments that by 1830 British parliamentary records list over 1,300 different ‘proprietary medicines’ (House of Commons Journal, 8 April 1830 ), the majority of which can be described as ‘quack’ cures. British patent medicines started to lose their dominance in the United States when they were denied access to the American market during the American Revolution, and lost further ground for the same reason during the War of 1812. From the early 19th century 'home-grown' American brands started to fill the gap, reaching their peak in the years after the American Civil War (Griffenhagen & Young 1957, Young 1961). British medicines never regained their previous dominance in North America, and the subsequent era of mass marketing of American patent medicines is usually considered to have been a "golden age" of quackery in the United States. This was mirrored by similar growth in marketing of quack medicines elsewhere in the world. In the United States, false medicines in this era were often denoted by the slang term snake oil. The quacks who sold them were called "snake oil peddlers", and usually sold their medicines with a fervent pitch similar to a fire and brimstone religious sermon. They often accompanied other theatrical and entertainment productions that travelled as a road show from town to town, leaving quickly before the falseness of their medicine could be discovered. Not all quacks were restricted to such small-time businesses however, and a number, especially in the United States, became enormously wealthy through national and international sales of their products. One among many possible examples is that of William Radam, a German immigrant to the USA who, in the 1880s, started to sell his ‘Microbe Killer’ throughout the United States and, soon afterwards, in Britain and throughout the British colonies. His concoction was widely advertised as being able to ‘Cure All Diseases’ (W. Radam, 1890) and this phrase was even embossed on the glass bottles the medicine was sold in. In fact, Radam's medicine was a therapeutically useless (and in large quantities actively poisonous) dilute solution of sulphuric acid, coloured with a little red wine (Young 1961). Radam's publicity material, particularly his books (see for example Radam, 1890), provide an illuminating insight into the role that pseudo-science started to play in the development and marketing of 'quack' medicines towards the end of the 19th century. Similar advertising claims to those of Radam can be found throughout the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. ‘Dr’ Sibley, an English patent medicine seller of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, even went so far as to claim that his Reanimating Solar Tincture would, as the name implies, ‘restore life in the event of sudden death’. Another English quack, ‘Dr Solomon’ claimed that his Cordial Balm of Gilead cured almost anything, but was particularly effective against all venereal complaints, from gonorrhoea to onanism. Although it was basically just brandy flavoured with herbs, it retailed widely at 33 shillings a bottle in the period of the Napoleonic wars, the equivalent of over $100 per bottle today. Not all patent medicines were without merit. Turlingtons Balsam of Life, first marketed in the mid 18th century, did have genuinely beneficial properties. This medicine continued to be sold under the original name into the early 20th century, and can still be found in the British and American Pharmacopoeias as ‘Compound tincture of benzoin’. The end of the road for the quack medicines now considered grossly fraudulent in the nations of North America and Europe came in the early 20th century. February 21st 1906 saw the passage into law of the Pure Food and Drug Act in the United States. This was the result of decades of campaigning by both government departments and the medical establishment, supported by a number of publishers and journalists (one of the most effective of whom was Samuel Hopkins Adams, whose series ‘The Great American Fraud’ was published in Colliers Weekly starting in late 1905). This American Act was followed three years later by similar legislation in Britain, and in other European nations. Between them, these laws began to remove the more outrageously dangerous contents from patent and proprietary medicines, and to force quack medicine proprietors to stop making some of their more blatantly dishonest claims.

Quackery today

Considered by many an archaic term, quackery is most often used to denote the peddling of the "cure-alls" described above. To use the term today is to level a serious objection to a medical practice which is not generally accepted by the medical community at large. This can mean that the practice under question is unproven according to scientific principles, though it does not necessarily mean that the technique does not produce the intended effects (see placebo effect for an example of how this might work). Quackery, in this context, is intended to mean a practice which, if studied comprehensively, would prove ultimately groundless. Many object to the application of this label to particular practices, often citing anecdotal evidence, faith-based reasons, or studies that some might call dubious.

Quackery can be found in any culture and in every medical tradition. Advertisements for "miracle cures" and "faith healing", as well as many natural remedies sold in health food stores, or certain diet and fitness regimes, are considered to be quackery by many conventional medical specialists.

A variety of medicines with heavy marketing campaigns may fall under the term "quackery". Full-page ads in magazines are popular places to sell these products or services, as well as web sites with exaggerated medical claims.

Most people with an e-mail account have experienced the marketing tactics of spamming — the current trend for miraculous penis enlargement, weight-loss remedies and unprescribed medicines of dubious quality sold on the Internet are perhaps the most common current form of quackery. Quackery has also become a serious problem in the field of autism, where medical sciences have made limited progress in the face of intractable neurodevelopmental disorders.

In the field of natural medicine, many practitioners prescribe natural remedies which they sell at a profit. This common practice could be viewed as a conflict of interest which is conducive to quackery (though this argument could be leveled at any profitable medical practice).

In the field of alternative medicine, many professions exist outside government regulation. Unregulated areas of medical practice are viewed to lend themselves to quackery, since peer review is an important component of establishing effective techniques.

Reasons quackery persists

Opponents of quackery have suggested several reasons why quackery is accepted by patients in spite of its lack of effectiveness:

- Ignorance: Those who perpetuate quackery may do so to take advantage of ignorance about conventional medical treatments versus alternative treatments.

- The placebo effect. Medicines or treatments known to have no effect on a disease can still affect a people's perception of their illness. People report reduced pain, increased well-being, improvement, or even total alleviation of symptoms. For some, the presence of a caring practitioner and the dispensation of medicine is curative in itself.

- Side effects from mainstream medical treatments. A great variety of pharmaceutical medications can have very distressing side effects, and many people fear surgery and its consequences, so they may opt to shy away from these mainstream treatments.

- Distrust of conventional medicine. Many people, for various reasons, have a distrust of conventional medicines (or of the regulating organizations themselves such as the FDA or the major drug corporations), and find that alternative treatments are more trustworthy.

- Cost. There are some people who simply cannot afford conventional treatment, and seek out a cheaper alternative. Nonconventional practitioners can often dispense treatment at a much lower cost.

- Desperation on the part of people with a serious or terminal disease, or who have been told by their practitioner that their condition is "untreatable". These people may seek out treatment, disregarding the availability of scientific proof for its effectiveness.

- Pride. Once a person has endorsed or defended a cure, or invested time and money in it, they may be reluctant to admit its ineffectiveness, and therefore recommend the cure that did not work for them to others.

- Fraud. Some practitioners, fully aware of the ineffectiveness of their medicine, may intentionally produce fraudulent scientific studies and medical test results, thereby confusing any potential consumers as to the effectiveness of the medical treatment.

- The Regression fallacy. Certain "self-limiting conditions", such as warts and the common cold, almost always improve, in the latter case in a rather predictable amount of time. A patient may associate the usage of alternative treatments with recovering, when recovery was inevitable.

References

Griffenhagen, George B.; James Harvey Young, "Old English Patent Medicines in America," Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology (U.S. National Museum Bulletin 218, Smithsonian Institution: Wash., 1959), 155-83.

Radam, W. (1890) Microbes and the microbe killer. Privately published. New York. 369pp.

Styles, J (2000). Product innovation in early modern London. In: Past & Present 168, 124 – 169.

Young, J. H. (1961) . The Toadstool Millionaires: A social history of patent medicines in America before federal regulation. Princeton University Press. 282pp.

External links

- Quackery: How Should It Be Defined?

- Quackery, Fraud and "Alternative" Methods: Important Definitions

- Quackwatch — Website with selected information about alleged quackery and health fraud, operated by Stephen Barrett, M.D. (retired)

- National Council Against Health Fraud

- Anti-Quackery Ring

- Healthfraud Discussion List

- "Fake Science — Episode 265". This American Life, May 21.

- Cures and Quackery: The Rise of Patent Medicines — 19th century miracle cures

- The Sciencist

- Quack Spiritualists: Ruining lives of common man in Pakistan

- Quackpot Watch An anti-'quackbuster' site