This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Theda (talk | contribs) at 04:08, 13 March 2006 (Reverted edits by 151.199.239.57 (talk) to last version by OneEuropeanHeart). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:08, 13 March 2006 by Theda (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 151.199.239.57 (talk) to last version by OneEuropeanHeart)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)"KKK" redirects here. For other uses, see KKK (disambiguation).

Ku Klux Klan (commonly abbreviated to KKK and also known as the Invisible Empire) refers to three entirely different movements in the United States. It refers to two influential organizations (in the 1860s and 1920s), as well as to small groups in recent years. The first KKK in the South in the late 1860s advocated white supremacy, and had a history of physically attacking or threatening its political opponents. In the 1920s the second KKK comprised thousands of local units that focused on opposition to crime, and often preached anti-Catholicism, nativism, and anti-Semitism. Today, the KKK, with operations in separated small local units, is considered an extreme hate group; the accusation that someone supports Klan programs results in highly negative attacks from mainstream media and political and religious leaders. The name, and many new terms, represented whimsical inventions of new words that sounded something like Greek words.

After numerous violent episodes a rapid reaction set in, with the Klan's leadership disowning it, and Southern elites seeing the Klan as an excuse for federal troops to continue their activities in the South. The organization was in decline from 1868 to 1870, and was destroyed in the early 1870s by President Ulysses S. Grant's vigorous action under the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act).

The second KKK was a deliberate echo of the first, though there was no connection. Founded in Georgia in 1915, it was a small group until 1922, when it began expanding rapidly all over the country. This second Klan fought to maintain the dominance of white Protestants over blacks, as well as Roman Catholics and Jews. This group, although preaching racism and often accused of violent activities, operated openly, and at its peak in the 1920s claimed millions of members. No major national politician claimed to be a member, and few prominent statewide politicians. Its popularity collapsed by 1928 due to scandals involving its own leaders.

The name Ku Klux Klan in the late 20th century was used by many different unrelated groups, including many who opposed the Civil Rights Act and desegregation in the 1960s. Today, dozens of organizations with chapters across the United States and other countries use all or part of the name in their titles, but their total membership is estimated to be only a few thousand.

Overview

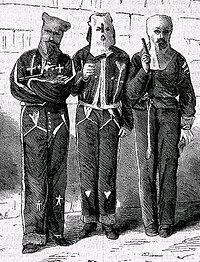

The Klan's first incarnation began in late 1865 or early 1866 in Pulaski, Tennessee. It was founded as a local social club, but quickly its main purpose became to resist Reconstruction after the American Civil War. It focused on intimidating Freedmen using terror and violence, and was involved in a wave of threats and killings of blacks in 1868. The organization was destroyed in the early 1870s by the federal government by President Ulysses S. Grant's vigorous action under the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act). The first Klan was never well organized. As a secret or "invisible" group, it had no membership rosters, no dues, no newspapers, no spokesmen, no chapters, no local officers, no state or national officials. Its popularity came from its reputation, and that was greatly enhanced by its outlandish costumes and its theatricality. As historian Elaine Frantz Parsons discovered :

"Lifting the Klan mask revealed a chaotic multitude of antiblack vigilante groups, disgruntled poor white farmers, wartime guerrilla bands, displaced Democratic politicians, illegal whiskey distillers, coercive moral reformers, bored young men, sadists, rapists, white workmen fearful of black competition, employers trying to enforce labor discipline, common thieves, neighbors with decades-old grudges, and even a few freedmen and white Republicans who allied with Democratic whites or had criminal agendas of their own. Indeed, all they had in common, besides being overwhelmingly white, southern, and Democratic, was that they called themselves, or were called, Klansmen."

Second KKK

In 1915, William J. Simmons founded a totally new group using the same name and costumes. It did not grow until the early 1920s; it then had a huge nationwide boom in membership. By 1924, it was in retreat and, by 1928, had dwindled to less than 5% of its original membership. This second Klan fought to maintain the dominance of moralistic white Protestants over "sinners"--especially bootleggers, adulterers, Blacks, Catholics, and Jews. The second KKK operated openly, and at its peak, in the 1920s, claimed millions of members in the South and Midwest. Many politicians at all levels of government were members, and, at its height, opponents claimed that it had secretly influenced some state governments, including Oregon and Indiana. Multiple scandals involving sex, murder and violence destroyed its reputation, and by 1928 only scattered remnants remained in isolated pockets.

The first Klan

Creation

The original Ku Klux Klan was created in an 1865 meeting in a law office by six Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee. It was, at first, a humorous social club centering on practical jokes and hazing rituals. From 1866 to 1867, various local units began breaking up black prayer meetings and invading black homes at night to steal firearms. Some of these activities may have been modeled on previous Tennessee vigilante groups such as the Yellow Jackets and Redcaps.

In an 1867 convention held in Nashville, the Klan was formalized as a national organization under a "Prescript" written by George Gordon, a former Confederate brigadier general. The Prescript states as the Klan's purposes:

- First: To protect the weak, the innocent, and the defenseless from the indignities, wrongs and outrages of the lawless, the violent and the brutal; to relieve the injured and oppressed; to succor the suffering and unfortunate, and especially the widows and orphans of the Confederate soldiers.

- Second: To protect and defend the Constitution of the United States...

- Third: To aid and assist in the execution of all constitutional laws, and to protect the people from unlawful seizure, and from trial except by their peers in conformity with the laws of the land.

In a word, the Klan's purpose was to resist the Congressional Reconstruction. The word "oppressed," for example, clearly refers to oppression by the Union Army, and "peers" implies that white Southern property holders should be protected from carpetbaggers, scalawags, and freedmen. During Reconstruction, the South was undergoing drastic changes to its social and political life. Southern Whites saw this as a threat to their supremacy as a race and sought to end this process.

The Prescript also includes a list of questions to be asked of applicants for membership, which confirms the focus on resisting Reconstruction and the Republican Party. The applicant is to be asked whether he was a Republican, a Union Army veteran, or a member of the Loyal League; whether he is "opposed to Negro equality both social and political;" and whether he is in favor of "a white man's government," "maintaining the constitutional rights of the South," "the reenfranchisement and emancipation of the white men of the South, and the restitution of the Southern people to all their rights," and "the inalienable right of self-preservation of the people against the exercise of arbitrary and unlicensed power."

According to one oral report, Gordon went to former slave trader and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest in Memphis and told him about the new organization, and, a few weeks later, Forrest was selected as Grand Wizard, the Klan's national leader.

Activities

The Klan sought to control the political and social status of the freedmen. Specifically, it attempted to curb black education, economic advancement, voting rights, and the right to bear arms. However, the Klan's focus was not limited to African Americans; Scalawags and Carpetbaggers (white Republicans) also became the target of intimidation tactics, and a wave of killing of hundreds of blacks in 1868, was primarily a political purge rather than a racial conflict. In some cases the violence achieved its purpose; in other counties the intimidation failed. The Republicans, organized Union Leagues, created their own armed defensive squads and fought back. Probably thousands were killed on both sides.

An 1868 proclamation by Gordon demonstrates several of the issues surrounding the Klan's violent activities.

- Many blacks were veterans of the Union Army, and were armed. From the beginning, one of the original Klan's strongest focuses was on confiscating firearms from Blacks. In the proclamation, Gordon warned that the Klan had been "fired into three times," and that if the Blacks "make war upon us they must abide by the awful retribution that will follow."

- Gordon also stated that the Klan was a peaceful organization. Such claims were common ways for the Klan to attempt to protect itself from prosecution.

- Gordon warned that some people had been carrying out violent acts in the name of the Klan. It was true that many people who had not been formally inducted into the Klan found the Klan's uniform to be a convenient way to hide their identities when carrying out acts of violence. However, it was also convenient for the higher levels of the organization to disclaim responsibility for such acts, and the secretive, decentralized nature of the Klan made membership fuzzy rather than clear-cut.

| Wikisource has the full text of the 1868 interview with Forrest. |

By this time, only two years after the Klan's creation, its activity was already beginning to decrease and, as Gordon's proclamation shows, to become less political and more simply a way of avoiding prosecution for violence. Many influential southern Democrats were beginning to see it as a liability, an excuse for the Federal government to retain its power over the South. Georgian B.H. Hill went so far as to claim "that some of these outrages were actually perpetrated by the political friends of the parties slain."

In an 1868 newspaper interview, Forrest boasted that the Klan was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men, and that although he himself was not a member, he was "in sympathy" and would "cooperate" with them, and could himself muster 40,000 Klansmen with five days' notice. He stated that the Klan did not see blacks as its enemy as much as the Loyal Leagues, Republican state governments like Tennessee governor Brownlow's, and other carpetbaggers and scalawags. There was an element of truth to this claim, since the Klan did go after white members of these groups, especially the schoolteachers brought south by the Freedmen's Bureau, many of whom had before the war been abolitionists or active in the underground railroad. Many white southerners believed, for example, that blacks were voting for the Republican Party only because they had been hoodwinked by the Loyal Leagues. Black members of the Loyal Leagues were also the frequent targets of Klan raids. One Alabama newspaper editor declared that "The League is nothing more than a nigger Ku Klux Klan."

Decline and suppression

Forrest's national organization, in fact, had little control over the local Klans, which were highly autonomous. One Klan official complained that his own "so-called 'Chief'-ship was purely nominal, I having not the least authority over the reckless young country boys who were most active in 'night-riding', whipping, etc., all of which was outside of the intent and constitution of the Klan..." Forrest ordered the Klan to disband in 1869, stating that it was "being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace." Due to the national organization's lack of control, this proclamation was more a symptom of the Klan's decline than a cause of it. Historian Stanley Horn writes that "generally speaking, the Klan's end was more in the form of spotty, slow, and gradual disintegration than a formal and decisive disbandment." A reporter in Georgia wrote in January 1870 that "A true statement of the case is not that the Ku Klux are an organized band of licensed criminals, but that men who commit crimes call themselves Ku Klux."

Although the Klan was being used more and more often as a mask for nonpolitical crimes, state and local governments seldom acted against it. In many states, there were fears that the use of black militiamen would ignite a race war. When Republican governor Holden of North Carolina called out the militia against the Klan in 1870, the result was a backlash that lost him the upcoming election.

Meanwhile, many Democrats at the national level were questioning whether the Klan even existed, or had been imagined by nervous Republican governors in the South. In January 1871, Pennsylvania Republican senator John Scott convened a committee which took testimony from 52 witnesses about Klan atrocities. Many Southern states had already passed anti-Klan legislation, and in February former Union general Benjamin Franklin Butler of Massachusetts (who was widely reviled by Southern whites) introduced federal legislation modeled on it. The tide was turned in favor of the bill by the governor of South Carolina's appeal for federal troops, and by reports of a riot and massacre in a Meridian, Mississippi, courthouse, which a black state representative escaped only by taking to the woods.

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant signed Butler's legislation, the Ku Klux Klan Act, which was used, along with the 1870 Force Act, to enforce the civil rights provisions of the constitution. Under the Klan Act, Federal troops were used rather than state militias, and Klansmen were prosecuted in Federal court, where juries were often predominantly black. Hundreds of Klan members were fined or imprisoned, and habeas corpus was suspended in nine counties in South Carolina. These efforts were so successful that the Klan was destroyed in South Carolina and decimated throughout the rest of the country, where it had already been in decline for several years. Prosecutions were led by Attorney General Amos Tappan Ackerman. The tapering off of the Federal government's actions under the Klan Act, ca. 1871–74, went along with the final extinction of the Klan, although in some areas similar activities, including intimidation and murder of black voters, continued under the auspices of local organizations such the White League, Red Shirts, saber clubs, and rifle clubs. Even though the Klan no longer existed, it had achieved many of its goals, such as denying voting rights to Southern blacks.

| Wikisource has the full text of the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act. |

The second Klan

Creation

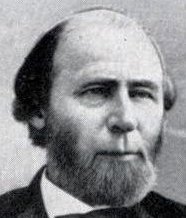

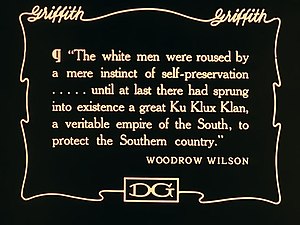

The founding of the second Ku Klux Klan in 1915 was a demonstration of the newfound power of the modern mass media. The film The Birth of a Nation was released, mythologizing and glorifying the first Klan. The second Ku Klux Klan was founded with a new anti-crime and anti-immigrant agenda to purify America. The bulk of the founders were from an organization calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan, and the new organization emulated the fictionalized version of the original Klan presented in The Birth of a Nation.

D. W. Griffith's 1915 movie The Birth of a Nation glorified the original Klan. The film's popularity and influence was massive and overwhelming. President Woodrow Wilson allowed it to be premiered at the White House as a favor to an old friend, but he said he did not endorse the content. Much of the modern Klan's iconography, including the standardized white costume and the burning cross, are imitations of the film, whose imagery was itself based on Dixon's romanticized concept of old Scotland rather than on the Reconstruction Klan.

Activities

Leaders of the second Klan had a new anti-crime, anti-bootlegger, anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic slant. This was consistent with the new Klan's greater success at recruiting in the U.S. Midwest than in the South.

This Klan was operated as a profit-making venture by its leaders, and participated in the boom in fraternal organizations at the time.

Political influence

The second Ku Klux Klan rose to great prominence and spread from the South into the Midwest region and Northern states and even into Canada. At its peak, Klan's purported membership exceeded million and comprised 20% of the adult white male population in many broad geographic regions, as high as 40% in some areas. No corroborative evidence for the high estimates exist; it was to the advantage of the Klan and its enemies to claim large numbers. Actual membership ledgers in Oregon and Indiana show the membership was not more than 5% of the men.

The KKK claimed many sympathetic officials, but no major state politician took orders from the Klan. Klan influence was particularly strong in Indiana, where Republican Edward Jackson was elected governor in 1924 with Klan support. He did not acknowledge membership. In one dramatic case in 1924 the Klan tried to make Anaheim, California, into a model Klan city; it secretly took over the city council, but was quickly voted out in a special recall election.

There weere no known Klan delegates at the played 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City. Dry William McAdoo faced wet Al Smith, who drew the opposition of the Klan because of his Catholicism. After days of stalemates, both candidates withdrew in favor of a compromise. McAdoo delegates defeated a platform plank that would have condemned their organization. On July 4, 1924, thousands of Klansmen converged on a nearby field in New Jersey where they participated in cross burnings, burned effigies of Smith, and celebrated the defeat of the platform plank denouncing them.

A few future politicians in the U.S. and Canada joined the Klan or flirted with membership. The list includes two Supreme Court justices; Senator Robert Byrd (D, West Virginia) was a Klan member in the early 1940s.

- Main article: Notable Ku Klux Klan members in national politics

Decline

The second Klan collapsed largely as a result of a scandal involving Republican David Stephenson, the Grand Dragon of Indiana and fourteen other states, who was convicted of the rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer in a sensational trial (she was bitten so many times that one man who saw her described her condition as having been "chewed by a cannibal").

As a result of these scandals, the Klan fell out of public favor in the 1930s and withdrew from political activity. Grand Wizard Hiram Evans sold the organization in 1939 to James Colescott, an Indiana veterinarian and Samuel Green, an Atlanta obstetrician, but they were unable to staunch the exodus of members. The Klan's image was further damaged by Colescott's association with Nazi-sympathizer organizations, the Klan's involvement with the 1943 Detroit Race Riot, and efforts to disrupt the American war effort during World War II. In 1944 the IRS filed a lien for $685,000 in back taxes against the Klan, and Colescott was forced to dissolve the organization in 1944. The name Ku Klux Klan then began to be used by a number of independent groups. The following table shows the decline in the Klan's estimated membership over time. (The years given in the table represent approximate time periods.)

| year | membership |

| 1920 | 4,000,000 |

| 1930 | 30,000 |

| 1970 | 2,000 |

| 2000 | 3,000 |

Folklorist and author Stetson Kennedy infiltrated the Klan after World War II and provided information, including secret code words, to the writers of the Superman radio program, resulting in a series of four episodes in which Superman took on the Klan. Kennedy intended to strip away the Klan's mystique, and the trivialization of the Klan's rituals and code words likely did have a negative impact on Klan recruiting and membership.

Later Ku Klux Klans

Following the demise of the second era KKK, there were three periods of resurgence, dubbed by some scholars and Klan participants as the third through sixth era Klans.

After World War II, the Klan's victims began to fight back. In a 1958 North Carolina incident, the Klan burned crosses at the homes of two Lumbee Native Americans who had associated with white people, and then held a nighttime rally nearby, only to find themselves surrounded by hundreds of armed Lumbees. Gunfire was exchanged, and the Klan was routed in what is known as The Battle of Hayes Pond.

In 1966, Stokely Carmichael was preaching Black Power methods to African American communities across Mississippi. He stated that the only way to end terror by whites, such as the Klan, was to meet them with armed resistance. As a result, several Blacks had their guns ready when the Klan came to harass their communities, and that caused the Klan to leave some communities once and for all.

A new focus of the postwar Conservative Klan was to resist the civil rights movement of the 1960s. In 1963, two Klan members carried out the bombing of a church in Alabama that had been used as a meeting place for civil rights organizers. Four young girls were killed, and outrage over the bombing helped to build momentum for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Klan used threats, intimidation, and murder to disrupt voter registration drives in the South, and to prevent registered black voters from voting. The Klan was involved in the 1964 murders of civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Mississippi, and also murdered Viola Liuzzo, a Southern-raised white mother of five who was visiting the South from her home in Detroit to attend a civil rights march.

In 1964, the FBI's COINTELPRO program began attempts to infiltrate and disrupt the Klan. COINTELPRO occupied a curiously ambiguous position in the civil rights movement, since it used its tactics of infiltration, disinformation, and violence against violent far-left and far-right groups such as the Klan and the Weathermen, but simultaneously against peaceful organizations such as Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. This ambivalence was shown dramatically in the case of the murder of Liuzzo, who was shot on the road by four Klansmen in a car, of whom one was an FBI informant. After she was murdered, the FBI spread false rumors that she was a communist, and that she had abandoned her children in order to have sex with black civil rights workers. Regardless of the FBI's ambivalence, Jerry Thompson, a newspaper reporter who infiltrated in the Klan in 1979, reported that COINTELPRO's efforts had been highly successful in disrupting the Klan; rival Klan factions both accused each other's leaders of being FBI informants, and one leader, Bill Wilkinson of the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, was, in fact, later revealed to have been working for the FBI.

Once the century-long struggle over black voting rights in the South had ended, the Klans shifted their focus to other issues, including affirmative action, immigration, and especially busing ordered by the courts in order to desegregate schools. In 1971, Klansmen used bombs to destroy ten school buses in Pontiac, Michigan, and charismatic Klansman David Duke was active in South Boston during the school busing crisis of 1974. Duke also made efforts to update its image, urging Klansmen to "get out of the cow pasture and into hotel meeting rooms." Duke was leader of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan from 1974 until he resigned from the Klan in 1978. In 1980, he formed the National Association for the Advancement of White People, a far-right white nationalist political organization. He was elected to the Louisiana State House of Representatives in 1989 as a Republican, even though the party threw its support to a different Republican candidate. In 1979, the Greensboro Massacre occurred in which five members of the Communist Workers Party were shot and killed while participating in an anti-Klan demonstration. The CWP had been active trying to organize black workers in Greensboro, North Carolina.

In this period, resistance to the Klan became more common. Jerry Thompson reported that in his brief membership in the Klan, his truck was shot at, he was yelled at by black children, and a Klan rally that he attended turned into a riot when black soldiers on an adjacent military base taunted the Klansmen. Attempts by the Klan to march were often met with counterprotests, and violence sometimes ensued.

Vulnerability to lawsuits has encouraged the trend away from central organization, as when, for example, the lynching of Michael Donald in 1981 led to a civil suit that bankrupted one Klan group, the United Klans of America. Thompson related how many Klan leaders who appeared indifferent to the threat of arrest showed great concern about a series of multimillion-dollar lawsuits brought against them as individuals by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a result of a shootout between Klansmen and a group of African Americans, and curtailed their activities in order to conserve money for defense against the suits. Lawsuits were also used as tools by the Klan, however, and the paperback publication of Thompson's book, My Life in the Klan, was canceled because of a libel suit brought by the Klan.

Klan activity has also been diverted into other racist groups and movements, such as Christian Identity, neo-Nazi groups, and racist subgroups of the skinheads.

Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

"Knights of the Ku Klux Klan" has been part of the title of at least ten organizations patterned on the original KKK. The most prominent of these was the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc., which was founded in November 1915 by William J. Simmons and disbanded in 1944 by James Colescott. At its peak, this organization had around three to five million members.

The most militant Klan group was "The White Knights of Mississippi" led by Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers. Though not the largest, they were by far the most violent. They were responsible for many bombings, church burnings, beatings, and murders, including the killing of three civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, along with Edgar Ray Killen, Wayne Roberts of Meridian, Mississippi and several other members of the Klan, murdered the three young men, who were all members of C.O.R.E, (Congress Of Racial Equality) by shooting them and burying their bodies in a dam outside of Philadelphia, Mississippi. Edgar Ray Killen was convicted of these murders in 2005, 40 years after they occurred. Price and Roberts are now deceased.

In 1989, The White Knights of Mississippi went national, and appointed Professional Wrestler Johnny Lee Clary, who was also known as Johnny Angel as its new national Imperial Wizard, to succeed Sam Bowers. Clary appeared on many talk shows including Oprah and Morton Downey Jr., in an effort to build a new modern image for the Ku Klux Klan. It was thought that Clary could build membership in the Klan due to his celebrity status as a professional wrestler. Clary tried to unify the various chapters of the Klan in a meeting held in the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, Pulaski, Tennessee, only to have it fall apart by infighting which occurred when the Klan came together. Clary's girlfriend was revealed to be an F.B.I informant, which resulted in mistrust of Clary among the different Klan members. Clary resigned from the Klan and later became a born again Christian and a civil rights activist.

In 2005, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (Knights Party) was headed by National Director Pastor Thom Robb, and based in Zinc, Arkansas. It is the biggest Klan organization in America today. The sixth era Klan continues to be a racist group, for example .

Robb's group in the past produced such Klan stars as David Duke, but it is now continuing a long, slow decline. In 1991, Thom Robb said that he foresaw imminent respectability for the Klan: "You take Exxon. They had an identity thing to overcome after that oil spill. Well, the Klan has an image problem to overcome, also."

The Ku Klux Klan today

Although often still discussed in contemporary American politics as representing the quintessential "fringe" end of the far-right spectrum, today the group only exists in the form of a number of very isolated, scattered "supporters" that probably do not number more than a few thousand. In a 2002 report on "Extremism in America", the Anti-Defamation League wrote "Today, there is no such thing as the Ku Klux Klan. Fragmentation, decentralization and decline have continued unabated." However, they also noted that the "need for justification runs deep in the disaffected and is unlikely to disappear, regardless of how low the Klan's fortunes eventually sink."

In some Klan units, anti-Catholicism has been dropped as a core principle; and, in some cases, Klan units have adopted neo-Nazism or Christian Identity as core ideological beliefs.

Today the only known former member of the Klan to hold a Federal office in the United States is Senator Robert Byrd, (D-WV), who says he "deeply regrets" his roles as "Exalted Cyclops" and "Kleagle," or recruiter, for his local Klan in the 1940's. During his campaign for the U.S. Senate in 1958, when Byrd was 41 years old, Byrd defended the Klan. He argued that the KKK had been incorrectly blamed for much of the violence in the South.

Californian musical sisters Prussian Blue also perform at modern Ku Klux Klan rallies.

Some of the larger KKK organizations currently in operation include:

- Church of the American Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

- Imperial Klans of America

- Knights of the White Kamelia

There are a vast number of smaller organizations.

In 2005, there were an estimated 3,000 Klan members, divided among 158 chapters of a variety of splinter organizations, about two-thirds of which were in former Confederate states. The other third were primarily in the Midwestern United States.

The American Civil Liberties Union has provided legal support to various factions of the KKK in defense of their First Amendment rights to hold public rallies, parades, and marches, and their right to field political candidates.

In a July 2005 incident, a Hispanic man's house was burned down in Hamilton, Ohio, after accusations that he sexually assaulted a nine-year-old white girl. Klan members in Klan robes showed up afterward to distribute pamphlets.

See also

- Jim Crow laws

- Silent Brotherhood

- Neo-Nazism

- History of the United States (1865-1918)

- Wide Awakes

- Knights of the Golden Circle

- American Protective Association

- Notable Ku Klux Klan members in national politics

- Aryan Brotherhood

Notes

- Klan membership claims peaked at about 4-5 million but seem wildly exaggerated to maximize their apparent power: http://www.aaregistry.com/african_american_history/2207/The_Ku_Klux_Klan_a_brief__biography, retrieved August 26 2005.

- The quote is from the 1868 Revised Precept, from Horn, 1939.

- Horn, 1939. Horn casts doubt on some other aspects of the story.

- http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-694, retrieved August 26 2005.

- Horn, 1939.

- Horn, 1939, p. 375.

- Wade, 1987, p. 102.

- Horn, 1939, p. 375.

- Cincinnati 'Commercial', August 28 1868, quoted in Wade, 1987. Full text of the interview on wikisource.

- Horn, 1939, p. 27.

- quotes from Wade, 1987.

- Horn, 1939, p. 360.

- Horn, 1939, p. 362.

- http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_enforce.html, retrieved August 11 2005.

- Wade, 1987, p. 85.

- Wade, 1987.

- Horn, 1939, p. 373.

- Wade, 1987, p. 88.

- http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_enforce.html, retrieved August 11 2005.

- Wade, 1987, p. 102.

- http://www.lib.duke.edu/forest/Research/ohisrch.html, retrieved August 11 2005. [http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_enforce.html

- Wade, 1987, pp. 109-110.

- http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/jbalkin/opeds/historylesson1.pdf (PDF), retrieved August 12 2005.

- http://faculty.smu.edu/dsimon/Change-CivRts2.html, retrieved August 15 2005.

- http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAliuzzo.htm, retrieved August 15 2005.

- New York Times, August 12 2005, p. A14.

- Dray, 2002.

- http://www.geocities.com/emruf5/birthofanation.html, retrieved July 7 2005.

- Dray, 2002, p. 198.

- Wade, 1987, p. 137.

- http://www.in.gov/statehouse/years/, retrieved Dec. 3, 2005

- http://www.aaregistry.com/african_american_history/2207/The_Ku_Klux_Klan_a_brief__biography, http://www.africanamericans.com/KuKluxKlan.htm, http://www.adl.org/hate-patrol/kkk.asp, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-2730, all retrieved August 26 2005.

- Ingalls, 1979; http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/jan2005/jan05.html, retrieved June 26 2005.

- Thompson, 1982.

- http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAkkk.htm, retrieved June 26 2005.

- http://www.adl.org/backgrounders/american_knights_kkk.asp, retrieved June 26 2005.

- http://stop-the-hate.org/klanbody.html, retrieved June 26 2005.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. Active U.S. Hate Groups in 2004. Intelligence Report. Retrieved April 5 2005 from http://www.splcenter.org/intel/map/hate.jsp.

- http://www.adl.org/backgrounders/american_knights_kkk.asp, retrieved June 26 2005.

- http://www.adl.org/hate-patrol/kkk.asp, retrieved August 26 2005.

- Axelrod, 1997, p. 160

References

General

- Newton, Michael, and Judy Ann Newton. The Ku Klux Klan: An Encyclopedia. Garland Publishing, 1991.

- Chalmers, David Mark. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. (Durham: Duke UP 3rd edition 1987).

- Wade, Wyn Craig. The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. New York: Simon and Schuster (1987). An unsympathetic account.

First Klan

- Edward John Harcourt; "Who Were the Pale Faces? New Perspectives on the Tennessee Ku Klux" Civil War History. Volume: 51. Issue: 1. (2005). pp: 23+.

- Horn, Stanley F. Invisible Empire: The Story of the Ku Klux Klan, 1866-1871, Patterson Smith Publishing Corporation: Montclair, NJ, 1939, a sympathetic portrait based on oral histories

- Christopher Long, "Ku Klux Klan" in Texas" (2005) covers 1866-1990

- Parsons, Elaine Frantz, "Midnight Rangers: Costume and Performance in the Reconstruction-Era Ku Klux Klan." The Journal of American History 92.3 (2005): 811-36

- Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction (Harper and Row, 1971).

- Lou Falkner Williams. The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials, 1871-1872 (2004)

Second Klan

- Alexander, Charles C. The Ku Klux Klan in the Southwest (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1965).

- Angle, Paul M. Bloody Williamson: A Chapter in American Lawlessness (1992)

- Feldman, Glenn. Politics, Society, and the Klan in Alabama, 1915-1949 (1999)

- Horowitz, David A. Inside the Klavern: The Secret History of a Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999), based on the minutes of a chapter in Oregon.

- Lay, Shawn, ed. The Invisible Empire in the West: Toward a New Historical Appraisal of the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press: 2003).

- Christopher Long, "Ku Klux Klan" in Texas (2005) covers 1866-1990

- Moore, Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1991).

- Maclean, Nancy. Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan. (NY: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- 2001 essay interpreting KKK by Professor John McClymer, Assumption College

- "Kansas Battles the Invisible Empire: The Legal Ouster of the KKK From Kansas, 1922-1927," by Charles William Sloan, Jr. Kansas Historical Quarterly Fall, 1974 (Vol. 40, No. 3), pp 393-409 details how KKK operated

Later Klans

- Chalmers, David Mark. Backfire: How the Ku Klux Klan Helped the Civil Rights Movement." (Rowman & Littlefield: 2003).

- Rose; Douglas D. The Emergence of David Duke and the Politics of Race University of North Carolina Press. 1992

- Thompson, Jerry. My Life in the Klan, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1982, ISBN 0399126953.

External links

- Ku Klux Klan website

- Imperial Klans of America Website

- The Southern Poverty Law Center Report

- The ADL on the KKK

- MIPT Terrorist Knowledge Base group profile for the KKK

- In 1999, South Carolina town defines the KKK as terrorist

- A long interview with Stanley F. Horn, author of Invisible Empire: The Story of the Ku Klux Klan, 1866-1871.

- Full text of the Klan Act of 1871 (simplified version)

- Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction Era (New Georgia Encyclopedia), scholarly

- Ku Klux Klan in the Twentieth Century (New Georgia Encyclopedia) scholarly

- Rank-and-File Radicalism within the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s (John Zerzan) a heterodox view of the KKK.

- The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), Alcohol, & Prohibition

- 1923 klan population map

Categories: