This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 130.209.6.40 (talk) at 14:48, 15 March 2006 (→Biography). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:48, 15 March 2006 by 130.209.6.40 (talk) (→Biography)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

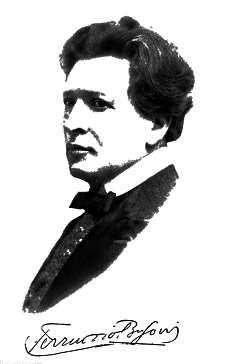

Dante Michaelangelo Benvenuto Ferruccio Busoni (April 1, 1866 – July 27, 1924) was an Italian composer, pianist, music teacher and conductor.

Biography

Busoni was born in Empoli in Italy, the only child of two professional musicians: his Italian/German mother a pianist, his Italian father a clarinetist. They were often touring during his childhood, and he was brought up in Trieste for the most part.

Busoni was a child prodigy. He made his public debut on the piano with his parents, at the age of seven. A couple of years later he played some of his own compositions in Vienna where he heard Franz Liszt play, and met Liszt, Johannes Brahms and Anton Rubinstein.

Busoni had a brief period of study in Graz before leaving to Leipzig in 1886. He subsequently held several teaching posts, the first in 1888 at Helsinki, where he met his wife, Gerda Sjöstrand. He taught in Moscow in 1890, and in the United States from 1891 to 1894 where he also toured as a virtuoso pianist.

In 1894 he settled in Berlin, giving a series of concerts there both as pianist and conductor. He particularly promoted contemporary music. He also continued to teach in a number of masterclasses at Weimar, Vienna and Basel, among his pupils being Claudio Arrau and Egon Petri.

In 1907, he penned his Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music, lamenting the traditional music "lawgivers", and predicting a future music that included the division of the octave into more than the traditional 12 degrees. His philosophy that "Music was born free; and to win freedom is its destiny," greatly influenced his students Luigi Russolo, Percy Grainger and Edgard Varèse, all of whom played significant roles in the 20th century opening of music to all sound.

During World War I, Busoni lived first in Bologna, where he directed the conservatory, and later in Zürich. He refused to perform in any countries that were involved in the war. He returned to Berlin in 1920 where he gave masterclasses in composition. He had several composition pupils who went on to become famous, including Kurt Weill, Edgard Varèse and Stefan Wolpe.

Busoni died in Berlin from a kidney disease. He was interred in the Städtischen Friedhof III, Berlin-Schöneberg, Stubenrauchstraße 43-45. He left a few recordings of his playing as well as a number of piano rolls. His compositions were largely neglected for many years after his death, but he was remembered as a great virtuoso and arranger of Bach for the piano. Around the 1980s there was a revival of interest in his compositions. He is commemorated by a plaque at the site of his last residence in Berlin-Schöneberg, Viktoria-Luise-Platz 11.

Busoni's music

The majority of Busoni's works are for the piano. Busoni's music is typically contrapuntally complex, with several melodic lines unwinding at once. Although his music is never entirely atonal in the Schoenbergian sense, his later works are often in indeterminate key. In the program notes for the premiere of his Sonatina seconda of 1912, Busoni calls the work senza tonalità (without tonality). Johann Sebastian Bach and Franz Liszt are often identified as key influences, though some of his music has a neo-classical bent, and includes melodies resembling Mozart's.

Some idea of Busoni's mature attitude to composition can be gained from his 1907 manifesto, Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music, a publication somewhat controversial in its time. As well as discussing then little-explored areas such as electronic music and microtonal music (both techniques he never employed), he asserted that music should distill the essence of music of the past to make something new.

Many of Busoni's works are based on music of the past, especially on the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. He arranged several of Bach's works for the piano, including the famous Toccata and Fugue in D Minor (originally for organ) and the chaconne from the D minor violin partita. Constructing a viable work of romantic piano literature from the solo violin to the piano is not only bold, it takes a man like Ferruccio Busoni with his inexorable feeling for musical geometry (requiring an in depth knowledge of integrating chord structures together by parts), and his "distinctive" sonority to pull it off. Earlier Brahms had also made a transcription of the same chaconne, but for left hand only. Thus some consider him an originator of neoclassicism in music.

The first version of Busoni's largest and best known solo piano work, Fantasia Contrappuntistica, was published in 1910. About half an hour in length, it is essentially an extended fantasy on the final incomplete fugue from Bach's The Art of Fugue. It uses several melodic figures found in Bach's work, most notably the BACH motif (B flat, A, C, B natural). Busoni revised the work a number of times and arranged it for two pianos. Versions have also been made for organ and for orchestra.

As well as those of Bach, Busoni used elements of other composers' works. The fourth movement of An die Jugend (1909), for instance, uses two of Niccolo Paganini's Caprices for solo violin (numbers 11 and 15), while the 1920 piece Piano Sonatina No. 6 (Fantasia da camera super Carmen) is based on themes from Georges Bizet's opera Carmen.

Busoni was a virtuoso pianist, and his works for piano are difficult to perform. The Piano Concerto (1904) is probably the largest such work ever written. It lasts for over an hour, requiring great stamina of the soloist, and is written for a large orchestra with a male voice choir in the last movement.

Busoni's suite for orchestra Turandot (1904), probably his most popular orchestral work, was expanded into his opera Turandot in 1917, and Busoni completed two other operas, Die Brautwahl (1911) and Arlecchino (1917). He began serious work on his best known opera, Doktor Faust, in 1916, leaving it incomplete at his death. It was then finished by his student Philipp Jarnach, who worked with Busoni's sketches as he knew of them, but in the 1980s Anthony Beaumont, the author of an important Busoni biography, created an expanded and improved completion by drawing on material that Jarnach did not have access to.

Busoni's editions

Busoni also edited of music by other composers. The best known of these is his edition of the complete Bach solo keyboard works, which he edited with the assistance of his students Egon Petri and Bruno Mugellini. He adds tempo markings, articulation and phrase markings, dynamics and metronome markings to the original Bach, as well as extensive performance suggestions. In the Goldberg Variations, for example, he suggests cutting eight of the variations for a "concert performance", as well as substantially rewriting many sections. The edition remains controversial, but has recently been reprinted.

On a smaller scale, Busoni edited works by Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Mozart. Liszt, Schoenberg and Schumann. The Busoni version of Liszt's La Campanella was championed by pianists such as Ignaz Friedman and Josef Lhevinne, and more recently by John Ogdon.

Recordings

Busoni made a considerable number of piano rolls, and a small number of these have been re-recorded onto vinyl record or CD. His recorded output on gramophone record is much smaller and rarer, unfortunately the rest were destroyed when the Columbia factory was burnt down. Originally a considerable number of works were recorded including Liszt's Sonata in B minor and Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata. The following pieces (recorded for Columbia) survive from February 1922:

- Prelude & Fugue No. 1 (Bach)

- Etude Op. 25 No. 5 (Chopin)

- Chorale Prelude "Nun freut euch liebe Christen" (Bach-Busoni)

- Ecossaisen (Beethoven)

- Prelude Op. 27 No. 7 & Etude Op. 10 No. 5 (Chopin) the two works are connected by an improvisatory passage

- Etude Op. 10 No. 5 (Chopin)

- Nocturne Op. 15 No. 2 (Chopin)

- Hungarian Rhapsody No. 13 (Liszt) this has substantial cuts, to fit it on two sides of a 78 record.

Busoni also mentions recording the Gounod-Liszt Faust Waltz in a letter to his wife in 1919. However, this recording was never released. Unfortunately for posterity, Busoni never recorded his original works.

The value of these recordings in ascertaining Busoni's performance style is a matter of some dispute. Many of his colleagues and students expressed disappointment with the recordings and felt they did not truly represent Busoni's pianism. His student Egon Petri was horrified by the piano roll recordings when they first appeared on LP and said that it was a travesty of Busoni's playing. Similarly, Petri's student Gunnar Johansen who had heard Busoni play on several occasions, remarked, "Of Busoni's piano rolls and recordings, only Feux follets (Liszt's 5th Transcendental Etude) is really something unique. The rest is curiously unconvincing. The recordings, especially of Chopin, are a plain misalliance". However, Kaikhosru Sorabji, a fervent admirer, found the records to be the best piano recordings ever made when they were released.

See also

References and external links

- A page on Busoni's transcriptions of Bach's organ compositions

- Larry Sitsky, Busoni and the Piano. Published 1986 by Greenwood Press.

- The Piano Quarterly Issue No. 108 (Winter 1979-80) has Busoni as the feature composer. Interviews with Gunnar Johansen and Guido Agosti.