This is an old revision of this page, as edited by MartinBotIII (talk | contribs) at 12:11, 31 July 2011 (→External links: fix MSDS link (jtbaker.com) using AWB). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:11, 31 July 2011 by MartinBotIII (talk | contribs) (→External links: fix MSDS link (jtbaker.com) using AWB)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name Hydrazinium hydrogen sulfate | |

| Other names Hydrazine sulphate | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.088 |

| EC Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

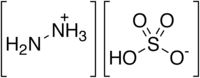

| Chemical formula | H6N2O4S |

| Molar mass | 130.12 g·mol |

| Solubility in water | 30 g/L (20°C) |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |

Hydrazine sulfate is the salt of hydrazine and sulfuric acid. Known by the trade name Sehydrin, it is a chemical compound that has been used as an alternative medical treatment for the loss of appetite (anorexia) and weight loss (cachexia) which is often associated with cancer. Hydrazine sulfate has never been approved in the US as safe and effective in treating any medical condition, although it is marketed as a dietary supplement. It is also sold over the Internet by websites that promote its use as a cancer therapy. It is used in palliative care for terminal cancer patients in Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union.

The main proponent of hydrazine sulfate as an anti-cancer agent is a U.S. physician named Joseph Gold, who developed the treatment in the mid-1970s. The use of hydrazine sulfate as a cancer remedy was popularized by the magazine Penthouse in the mid 1990s, when Kathy Keeton, wife and business partner of the magazine's publisher Bob Guccione, used it in an attempt to treat her metastatic breast cancer. Keeton (until her death in 1997) and other supporters of hydrazine sulfate treatment accused the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) of deliberately hiding the beneficial effects of the compound, and threatened to launch a class action law suit. The NCI denied the claims, and says that there is little to no evidence that hydrazine sulfate has any beneficial effects whatsoever. The position of the NCI was supported by an inquiry held by the General Accounting Office.

A review of the clinical research concluded that hydrazine sulfate has never been shown to act as an anticancer agent; patients do not experience remissions or regressions of their cancer, and patients do not live longer than non-treated patients. Some academic reviews of alternative cancer treatments have described the compound as a "disproved and ineffective treatment for cancer", while other more positive reviews describe its value as a supplementary cancer therapy to be "uncertain" and requiring further research to substantiate.

Hydrazine sulfate also has a variety of uses in the chemical industry.

Chemistry

Hydrazine sulfate is a commercially available form of hydrazine. It is a white solid, prepared by reacting an aqueous solution of hydrazine with sulfuric acid: it is soluble in water, and the original hydrazine can be reformed by simply adjusting the pH. It has a number of laboratory uses in analytical chemistry and organic synthesis.

It may be preferred over pure hydrazine or hydrazine hydrate for laboratory use because it is easily purified if necessary (by recrystallization from water), and it is less volatile and less susceptible to atmospheric oxidation on storage. These same properties make it the preferred form of hydrazine for dietary supplements and pharmaceutical trials. It is relatively inexpensive, with 100 grams of analytical grade hydrazine sulfate costing about USD20, and 100 tablets or capsules (60 milligrams hydrazine sulfate) costing USD20–60.

Industrial uses

Hydrazine sulfate also has a variety of uses in industrial chemistry, including as a chemical intermediate, as a catalyst in making fibers out of acetate, as a fungicide, antiseptic, in the analysis and synthesis of minerals and testing for arsenic in metals.

Background

Hydrazine sulfate was specifically developed as a result of a proposal by Joseph Gold for a therapy that could offset the rapid loss of weight that occurs in cancer (cancer cachexia). This hypothesis was based on the fact that cancer cells are often unusually dependent on glycolysis for energy (the Warburg effect), Gold proposed that the body might offset this increased glycolysis using gluconeogenesis, which is the pathway that is the reverse of glycolysis. Since this process would require a great deal of energy, Gold thought that inhibiting gluconeogenesis might reverse this energy requirement and be an effective treatment for cancer cachexia. Hydrazine is a reactive chemical that in the test tube can inactivate one of the enzymes needed for gluconeogenesis, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEP-CK). It was also postulated that if tumor energy gain (glycolysis) and host-energy loss (gluconeogenesis) were functionally interrelated, inhibition of gluconeogenesis at PEP CK could result in actual tumor regression in addition to reversal or arrest of cancer cachexia. In this model, hydrazine sulfate is therefore thought to act by irreversibly inhibiting the enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase.

Clinical trials

Joseph Gold, the developer and principal proponent of hydrazine sulfate, has published several papers arguing that the compound is an effective cancer treatment. These data have been questioned by the American Cancer Society and other investigators have been unable to repeat or confirm these results. Gold is reported not to trust the motives or results of other investigators, with CNN quoting him as stating that "they've been out to get hydrazine sulfate, and I don't know why".

In response to these results, an uncontrolled clinical trial was carried out at the Petrov Research Institute of Oncology in St. Petersburg over a period of 17 years, and a controlled trial was carried out at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in California over period of 10 years, respectively. The Russian trial reported complete tumor regression in about 1% of cases, a partial response in about 3% of cases and some subjective improvement of symptoms in about half of the patients. The National Cancer Institute analysis of this trial notes that interpretation of these data is difficult, due to the absence of controls, the lack of information on prior treatment and the study's reliance on subjective assessments of symptoms (i.e. asking patients if the drug had made them feel any better). Overall, the trials in California saw no statistically-significant effect on survival from hydrazine sulfate treatment, but noted increased calorie intake in treated patients versus controls. The authors also performed a post-hoc analysis on one or more subgroups of these patients, which they reported as suggesting a beneficial effect from treatment. The design and interpretation of this trial, and in particular the validity of this subgroup analysis, was criticized in detail in an editorial in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Later randomized controlled trials trials failed to find any improvement in survival, For example, in a trial of the treatment of advanced lung cancer, with either cisplatin and vinblastine or these drugs plus hydrazine sulfate, saw complete tumor regression in 4% of the hydrazine group, versus 3% in the control group, and tumor progression in 36% of the hydrazine group, versus 30% of the control group; however, none of these differences were statistically significant. Some trials even found both significantly decreased survival and significantly poorer quality of life in those patients receiving hydrazine sulfate. These consistently negative results have resulted in hydrazine sulfate being described as a "disproven cancer therapy" in a recent medical review. Similarly, other reviews have concluded that there is "strong evidence" against the use of hydrazine sulfate to treat anorexia or weight loss in cancer patients.

Side effects

Hydrazine sulfate is toxic and carcinogenic. Nevertheless, the short-term side effects reported in various clinical trials are relatively mild: minor nausea and vomiting, dizziness and excitement, polyneuritis (inflammation of the nerves) and difficulties in fine muscle control (such as writing). However, more serious, even fatal side effects have been reported in rare cases: one patient developed fatal liver and kidney failure, and another developed serious symptoms of neurotoxicity. These side effects and other reports of hydrazine toxicity are consistent with the hypothesis that hydrazine may play a role in the toxicity of the antibiotic isoniazid, which is thought to be metabolized to hydrazine in the body.

Hydrazine sulfate is also a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), and is incompatible with alcohol, tranquilizers and sleeping pills (benzodiazepines and barbiturates), and other psycho-active drugs, with pethidine (meperidine, Demerol), and with foods containing significant amounts of the amino acid tyrosine, such as most cheeses, raisins, avocados, processed and cured fish and meats, fermented products, and others.

References

- Chlebowski, R. T.; Bulcavage, L.; Grosvenor, M.; et al. (1987), "Hydrazine Sulfate in Cancer Patients With Weight Loss. A Placebo-Controlled Clinical Experience", Cancer, 59 (3): 406–10, doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19870201)59:3<406::AID-CNCR2820590309>3.0.CO;2-W, PMID 3791153

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Brauer, M.; Inculet, R. I.; Bratnager, G.; Marsh, G. D.; Driedger, A. A.; Thompson, R. T. (1994), "Insulin Protects against Hepatic Bioenergetic Deterioration by Cancer Cachexia. An in-Vivo P Magnetic Resonance Study", Cancer Research, 54 (24): 6383–86, PMID 7987832

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Chlebowski, R. T.; Bulcavage, L.; Grosvenor, M.; Oktay, E.; Block, J. B.; Chlebowski, J. S.; Ali, I.; Elashoff, R. (1990), "Hydrazine Sulfate Influence on Nutritional Status and Survival in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer", Journal of Clinical Oncology, 8 (8): 9–15, PMID 1688616

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Gold, J. (1999), "Long term complete response in patient with advanced, localized NSCLC with hydrazine sulfate, radiation and Carboplatin, refractory to combination chemotherapy", Proceedings of the American Association for Cancer Research (40): 642. Abstract.

- ^ Questions and answers about hydrazine sulfate, National Cancer Institute, March 12, 2009

- ^ Black, M.; Hussain, H. (2000), "Hydrazine, Cancer, the Internet, Isoniazid, and the Liver" (PDF), Annals of Internal Medicine, 133 (11): 911–13, PMID 11103062

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Filov, V. A.; Gershanovich, M. L.; Danova, L. A.; Ivin, B. A. (1995), "Experience of the Treatment with Sehydrin (Hydrazine Sulfate, HS) in the Advanced Cancer Patients", Investigational New Drugs, 13 (1): 89–97, doi:10.1007/BF02614227, PMID 7499115

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - London, William M. (July 23, 2006), Penthouse's promotion of hydrazine sulfate

- Goldberg, Burton (June 12, 2000), Holding the National Cancer Institute Accountable for Cancer Deaths

- Goldberg, Burton; Trivieri, Larry; Anderson, John W., ed. (2002), Alternative medicine: the definitive guide (2nd ed.), Celestial Arts, pp. 50–51, 598, ISBN 1587611414

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link). - Jenks, S. (1993), "Hydrazine Sulfate Ad Is "Offensive"", Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85 (7): 528–29, doi:10.1093/jnci/85.7.528, PMID 8455198.

- Nadel, M. V. (September 1995), "Cancer Drug Research—Contrary to Allegations, Hydrazine Sulfate Studies Were Not Flawed", Report to the Chairman and Ranking Minority Member, Human Resources and Intergovernmental Relations Subcommittee, House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, Washington, D.C.: General Accounting Office, Document No. HEHS-95-141.

- ^ Kaegi, Elizabeth (1998), "Unconventional therapies for cancer: 4. Hydrazine sulfate. Task Force on Alternative Therapies of the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Initiative", Canadian Medical Association Journal, 158 (10): 1327–30, PMC 1229327, PMID 9614826.

- Green, Saul (1997), "Hydrazine sulfate: is it an anticancer agent?", Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, 1: 19–21

- Hydrazine sulfate / Hydrazine sulphate from the British Columbia Cancer Agency

- ^ Vickers A (2004), "Alternative cancer cures: "unproven" or "disproven"?", CA Cancer J Clin, 54 (2): 110–8, doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.110, PMID 15061600

- ^ Milne, George W. A. (2005). Gardner's commercially important chemicals: synonyms, trade names, and properties. New York: Wiley-Interscience. pp. 325. ISBN 0-471-73518-3.

- ^ Adams, Roger; Brown, B. K. (1922). "Hydrazine sulfate". Organic Syntheses. 2: 37

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 1, p. 309. - Gold, J. (1968), "Proposed Treatment of Cancer by Inhibition of Gluconeogenesis", Oncology, 22 (2): 185–207, doi:10.1159/000224450, PMID 5688432.

- Gold, J. (1974), "Cancer Cachexia and Gluconeogenesis", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 230 (1 Paraneoplasti): 103–10, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb14440.x, PMID 4522864.

- Gold J (1987), "Hydrazine sulfate: a current perspective", Nutr Cancer, 9 (2–3): 59–66, doi:10.1080/01635588709513912, PMID 3104888

- "Editorial: Unproven methods of cancer management: hydrazine sulfate", CA Cancer J Clin, 26 (2): 108–10, 1976, doi:10.3322/canjclin.26.2.108, PMID 816429

- Elizabeth Cohen Regulators warn about online cancer 'cures' CNN December 5, 2000

- Hydrazine sulfate:Human/Clinical Studies National Cancer Institute

- ^ Chlebowski RT, Bulcavage L, Grosvenor M; et al. (1990), "Hydrazine sulfate influence on nutritional status and survival in non-small-cell lung cancer", J. Clin. Oncol., 8 (1): 9–15, PMID 1688616

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Piantadosi, S. (1990), "Hazards of small clinical trials" (PDF), Journal of Clinical Oncology, 8 (1): 1, PMID 2295901, retrieved 2009-06-03

- Loprinzi CL, Goldberg RM, Su JQ; et al. (1994), "Placebo-controlled trial of hydrazine sulfate in patients with newly diagnosed non-small-cell lung cancer", J. Clin. Oncol., 12 (6): 1126–9, PMID 8201374

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kosty MP, Fleishman SB, Herndon JE; et al. (1994), "Cisplatin, vinblastine, and hydrazine sulfate in advanced, non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind phase III study of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B", J. Clin. Oncol., 12 (6): 1113–20, PMID 8201372

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Herndon JE, Fleishman S, Kosty MP, Green MR (1997), "A longitudinal study of quality of life in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 8931", Control Clin Trials, 18 (4): 286–300, doi:10.1016/0197-2456(96)00116-X, PMID 9257067

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Loprinzi CL, Kuross SA, O'Fallon JR; et al. (1994), "Randomized placebo-controlled evaluation of hydrazine sulfate in patients with advanced colorectal cancer", J. Clin. Oncol., 12 (6): 1121–5, PMID 8201373

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yavuzsen T, Davis MP, Walsh D, LeGrand S, Lagman R (2005), "Systematic review of the treatment of cancer-associated anorexia and weight loss", J. Clin. Oncol., 23 (33): 8500–11, doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.01.8010, PMID 16293879

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gagnon B, Bruera E (1998), "A review of the drug treatment of cachexia associated with cancer", Drugs, 55 (5): 675–88, doi:10.2165/00003495-199855050-00005, PMID 9585863

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hydrazine Hazard Summary, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, January 2000.

- Section 9.2.1, Environmental Health Criteria for Hydrazine, International Programme on Chemical Safety, 1987.

- Hainer, M. I.; et al. (2000), "Fatal hepatorenal failure associated with hydrazine sulfate" (PDF), Annals of Internal Medicine, 133 (11): 877–80, PMID 11103057

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help). - Nagappan, R.; Riddell, T. (2000), "Pyridoxine therapy in a patient with severe hydrazine sulfate toxicity", Critical Care in Medicine, 28 (6): 2116–18, doi:10.1097/00003246-200006000-00076, PMID 10890675

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - National Cancer Institute (1999), "Hydrazine Sulfate", PDQ Complementary/Alternative Medicine

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Proponents

- Critics

- Hydrazine Sulfate: Is It an Anticancer Agent? Quackwatch

- The Penthouse Politics of Cancer: The Promotion of Hydrazine Sulfate and a Medical Conspiracy Theory American Council on Science and Health

- Governmental and medical

- Hydrazine sulfate / Hydrazine sulphate British Columbia Cancer Agency

- What is rocket fuel treatment? Cancer Research UK

- Hydrazine Sulfate American Cancer Society

- Hydrazine Sulfate University of Minnesota, Cancer Information

- Hydrazine Sulfate, Detailed Scientific Review The University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center

- Physical and chemical hazards

- Hydrazine sulfate Material safety data sheet