This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Future Perfect at Sunrise (talk | contribs) at 14:58, 9 August 2011 (rv, unexplained change to figures). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:58, 9 August 2011 by Future Perfect at Sunrise (talk | contribs) (rv, unexplained change to figures)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| An editor has nominated this article for deletion. You are welcome to participate in the deletion discussion, which will decide whether or not to retain it.Feel free to improve the article, but do not remove this notice before the discussion is closed. For more information, see the guide to deletion. Find sources: "Slavic dialects of Greece" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR%5B%5BWikipedia%3AArticles+for+deletion%2FSlavic+dialects+of+Greece+%282nd+nomination%29%5D%5DAFD |

| This article may contain citations that do not verify the text. Please check for citation inaccuracies. (May 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article contains too many pictures for its overall length. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please improve this article by removing indiscriminate collections of images or adjusting images that are sandwiching text in accordance with the Manual of Style on use of images. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Eastern South Slavic |

||||||

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

Alphabets

|

||||||

The Slavic dialects of Greece are the dialects of Macedonian and Bulgarian spoken by minority groups in the regions of Macedonia and Thrace in northern Greece. Usually, these dialects are classified as either Bulgarian or Pomak in Thrace, transitional dialects in East Macedonia, and Macedonian in Central and West Macedonia. Until the official codification of the Macedonian language in 1944 many linguists considered all the dialects to be Bulgarian. This has remained the predominant opinion in Bulgarian linguistics and dialectology and the position of the Bulgarian governments, and it is also supported by some international scholars.

History

Slavic tribes began settling in the region of Macedonia and Thrace in the 6th century. In the following centuries these two peoples mixed together. During Ottoman rule, most of the Orthodox-Bulgarian population of Macedonia had not formed a national identity separate from the Bulgarians in Moesia and Thrace and were instead identified through their religious affiliation. In the Middle Ages and later, until the 20th century, the Slav-speaking population of Aegean Macedonia was identified mostly as Bulgarian or Greek. The Muslim Slavic-speakers in Western Thrace, known as Pomaks, self-identified themselves predominantly as Turks, because Turks and Pomaks were part of the same millet during the years of the Ottoman Empire. After World War I, new Slav Macedonian (Greek: Σλαβομακεδόνας) nationalism began to arise. In 1934 the Comintern issued a declaration supporting the development of Macedonian nationalism However today the vast majority of this people espouse a Greek national identity and are bilingual in Greek. The fact that the majority of these people self-identify as Greeks makes their numbers uncertain.

20th century

As languages were codified in the 19th and 20th century, many people began to identify their language as Bulgarian and later Macedonian. After the Balkan wars and World War I, many Slavs from Greek Macedonia who identified as Bulgarians left Greece for Bulgaria. After the Second World War many Bulgarians left Greece. After the Greek Civil War, many Macedonian speakers also left Greece

On August 4, 1936 the authoritarian regime of General Metaxas came to power, and a new state sponsored policy of Hellenisation was enacted. The aim was to Hellenise all the non-Greek speaking Orthodox Christian populations within the Greek state's territory; other Balkan countries (Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania and Albania) respectively followed similar policies. In Greece, the ensuing result left the Slavic speakers (and other minority speech communities) forcibly suppressed, and their privileges under the Treaty of Sèvres withdrawn. Policies of the Metaxas regime included forcible Hellenization of personal and surnames, punishment for speaking a non-Greek language and changing of all Slavic toponyms.

The 1951 Greek census reported c. 40,000 people who declared their mother language to be Slavic or Slav-Macedonian. Since then, no Greek census has asked questions regarding mother language. According to a study by anthropologist Ricki van Boeschoten, 64% of the inhabitants of 43 villages in the Florina area were Macedonian language speakers.

Present situation

At present, the number of Slavophones in Greece is unknown. In the latest census posing a question on mother tongue (1951), 41,017 people declared themselves speakers of Slavic. Almost all Slavic speakers today in Greek Macedonia also speak Greek and most regard themselves as ethnically and culturally Greek. Many of those for whom a non-Greek identity was particularly important have tended to leave Greece during the past eighty years. Very few speakers can understand written Macedonian and Bulgarian and according to Euromosaic, the dialects spoken in Greece are mutually intelligible as is the case with the Macedonian and Bulgarian languages. Some linguists used the term "Greek-Slavic" instead of the confusing interchangeable terms "Macedonian" and "Bulgarian".

Self-identification

The linguistic affiliation of these varieties with either of the two neighbouring standard languages is a matter of some discussion, as is the ethnic affiliation of their speakers. Locally and in the Greek language they are often referred to simply as "Slavic" (σλάβικα slávika) or "local" (εντόπια Entópia, Dópia). Among self-identifying terms, makedonski ("Macedonian"), bălgarski ("Bulgarian", balgàrtzki, bolgàrtski or bulgàrtski in the region of Kostur, bògartski in Dolna Prespa ) and Pomatskou ("Pomak") are also used along with naši ("our own") and stariski ("old").

Distribution

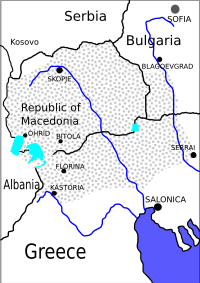

The distribution of the Macedonian and Bulgarian languages in Greece varies widely. Much of the population is concentrated in the prefectures of Florina, Kastoria, Pella, Kilkis and Imathia, with a smaller Bulgarian-speaking population in Thrace. There has never been a large Slavic-speaking population in the Chalcidice, Pieria and Kavala.

Population estimates

The exact numbers of speakers in Greece is hard to ascertain. Jacques Bacid estimates in 1983 in his book that "over 200,000 Macedonian speakers remained in Greece". Other sources put the numbers of speakers at 180,000 , 220,000 250,000 and 300,000. The Reader's Digest World Guide. puts the figure of Ethnic Macedonians in Greece at 1.8% or c.200,000 people and that for Pomaks at 0.9% or c.100,000 people, with the native language roughly corresponding with the figures. The UCLA also states that there is 200,000 Macedonian speakers in Greece and 30,000 Bulgarian speakers.. A 2008 article in the Greek newspaper Eleftherotipia put the estimate at 20,000.

This refers to speakers regardless of Ethnic identity. No information is given regarding how the figures were obtained.

Political representation

A political party that promotes the concept and rights of the "Macedonian minority in Greece", and wider use of the Macedonian language - the Rainbow Party (Template:Lang-el, Template:Lang-mk) - was founded in September 1998, and received 2,955 votes in the region of Macedonia in the 2004 elections. Rainbow didn't participate in the Greek legislative election, 2007 citing financial reasons. Several ethnic Macedonian members of Rainbow have been elected to public office, such as Petros Dimtsis in Florina and Pando Ašlakov (Panagiotis Anastasiadis) as the mayor of Meliti (Ovčarani), alongside other ethnic Macedonian mayors in Vevi, Neochoraki, Achlada and Pappagiannis.

In 2009, another pro-Macedonian organisation, the Educative and Cultural Movement of Edessa was founded in the city of Edessa. The group currently engages itself with teaching the Macedonian language, publishing the Macedonian language newspaper, Zadruga (Template:Lang-mk), and in engaging with other Macedonian minorities living in Bulgaria and Macedonians in Albania.

Classification and dialects

It is generally accepted that both Macedonian and Bulgarian are spoken in the north of Greece. They are split into three major groups: Macedonian, transitional dialects, and Bulgarian. This opinion is not accepted by Bulgarian authors who consider all of these dialects, and the Macedonian language as a whole to be part of the Western Bulgarian dialects.

According to Peter Trudgill,

There is, of course, the very interesting Ausbau sociolinguistic question as to whether the language they speak is Bulgarian or Macedonian, given that both these languages have developed out of the South Slavonic dialect continuum that embraces also Serbian, Croatian, and Slovene. In former Yugoslav Macedonia and Bulgaria there is no problem, of course. Bulgarians are considered to speak Bulgarian and Macedonians Macedonian. The Slavonic dialects of Greece, however, are "roofless" dialects whose speakers have no access to education in the standard languages. Greek non-linguists, when they acknowledge the existence of these dialects at all, frequently refer to them by the label Slavika, which has the implication of denying that they have any connection with the languages of the neighboring countries. It seems most sensible, in fact, to refer to the language of the Pomaks as Bulgarian and to that of the Christian Slavonic-speakers in Greek Macedonia as Macedonian.

According to Roland Schmieger,

Apart from certain peripheral areas in the far east of Greek Macedonia, which in our opinion must be considered as part of the Bulgarian linguistic area (the region around Kavala and in the Rhodope Mountains, as well as the eastern part of Drama nomos), the dialects of the Slav minority in Greece belong to the Macedonian diasystem.

Macedonian Language

Further information: Dialects of the Macedonian language

Various dialects of the Macedonian language are spoken in the peripheries of West and Central Macedonia. The dialects of the Macedonian language spoken in Greece include the Upper and Lower Prespa dialects, the Kastoria dialect, the Nestram-Kostenar dialect, the Florina variant of the Prilep-Bitola dialect and the Salonica-Edessa dialect. Certain characteristics of the these dialects include the changing of the suffix ovi to oj creating the words лебови> лебој (lebovi> leboj/ bread). Often the intervocalic consonants of /v/, /g/ and /d/ are lost, changing words from polovina >polojna (a half) and sega > sea (now). In other phonological and morphological characteristics, they remain similar to the other South-Eastern dialects spoken in the Republic of Macedonia and Albania.

Transitional dialects

The Ser-Drama-Lagadin-Nevrokop dialect is considered a transitional dialects between Macedonian and Bulgarian in Macedonian dialectology. In Bulgarian dialectology, Drama-Ser dialect and Solun dialect are considered Eastern Bulgarian dialects which are transitory between the Western and Eastern Bulgarian dialects and are grouped as West-Rupian dialects, part of the large Rupian dialect massif of Rhodopes and Thrace . They are spoken in the peripheral region of East Macedonia along with a small population in Bulgaria. The Bulgarian vowels of я /ja/ and Й /ji/ are kept, transforming words such as николаи/nikolai into николай/nikolaĭ and Кои/Koj into Кой/Koĭ. Macedonian and Western Bulgarian words like Бел/Bel convert to the Eastern Bulgarian form of бял /bʲal/ (white). Old Church Slavonic ръ/рь and лъ/ль are pronounced as ər and əl, respectively (cf. ръ~ър (rə~ər) and лъ~ъл (lə~əl) in Standard Bulgarian and vocalic r~oл (ɔl) in Standard Macedonian). Likewise, Old Church Slavonic yus and ъ are both pronounced as in Bulgarian, rather than and , as in Macedonian. The /h/ phoneme also adopts the Bulgarian pronunciation of (kh). The dialects also have many similarities to both the Bulgarian and Macedonian standards are often placed in both.

Bulgarian language and the Pomak dialects

Further information: Bulgarian dialects

The Bulgarian Language in Western Thrace is called in Greece the "Pomak language" or the "Pomak dialects". The Pomak dialects are mainly spoken and taught at primary school level in the Pomak regions of Greece, which are primarily in the Rhodope Mountains. The language in Greek is known as 'Pomatskou' and taught in the Greek alphabet. The main school manual is 'Pomaktsou' by Moimin Aidin and Omer Hamdi, Komotini 1997. There is also a Pomak-Greek dictionary by Ritvan Karahodja, 1996. The number of Pomaks ranges from 30,000 to 90,000 whose presence dates from the days of the Byzantine empire. It is used by many of the Pomak speakers on either side of the Bulgarian-Greek border. The dialects are on the Eastern side of the Yat isogloss of Bulgarian, yet many pockets of western Bulgarian speakers remain. The standard Bulgarian language is not taught in Greece.

Many Greek linguists do not classify the Slavic languages spoken in Greece to be part of any particular standard language.

|

Education

During the late 19th and early 20th century Bulgarian was taught in the Bulgarian Exarchate's schools. Under the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920 (which was never ratified ), Greece undertook the obligation to open schools for minority-language children. In 1925 the government of Greece submitted copies of a schoolbook called Abecedar, which was written in the Prilep-Bitola dialect of Macedonian, for the Slavophone children and published by the Greek Ministry of Education, to the League of Nations as evidence that they were carrying out these obligations.

Abecedar was written in a newly adapted variety of the Latin alphabet for the Slavic language in Greece, and not in the Cyrillic alphabet which was the official alphabet of neighboring Bulgaria and Serbia - this also shows the intent of the Greek government to create a distinctively Slavic minority, not a Bulgarian or Serbian minority; the result being that Bulgaria and Serbia would have no right to interfere in Greece's internal affairs. In the 1930s the Metaxas regime banned the Slavic language in public and private use.

During the 1941–1944 period, the Bulgarian language was taught in the regions of Greece annexed to Bulgaria.

During the Greek Civil War, the Macedonian language was taught in 87 schools with 10,000 students in areas of northern Greece under the control of Communist-led forces, until their defeat by the National Army in 1949. After the war, all of these Macedonian language schools were closed down.

More recently there have been attempts to once again begin education in Macedonian. In 2009 the Educational and Cultural Movement of Edessa began to run Macedonian language courses in Edessa (Template:Lang-mk), teaching the Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet and Macedonian language. Macedonian language courses have also begun in Salonika, as a way of further encouraging use of the Macedonian language. These courses have since been extended to include classes for Macedonian speakers in Florina and Edessa.

In 2006 the Macedonian language primer Abecedar was reprinted in an informal attempt to reintroduce Macedonian language education The Abecedar primer was reprinted in 2006 by the Rainbow, Political Party, it was printed in Macedonian, Greek and English. The book is being distributed to people who identify as Macedonian speakers in northern Greece and it has been successfully promoted in the city of Salonika .In the absence of greater Macedonian language books printed in Greece, young Macedonians living in Greece use books originating from the Republic of Macedonia in which they can study the Macedonian language

See also

References

- Mladenov, Stefan. Geschichte der bulgarischen Sprache, Berlin, Leipzig, 1929, § 207-209.

- Mazon, Andre. Contes Slaves de la Macédoine Sud-Occidentale: Etude linguistique; textes et traduction; Notes de Folklore, Paris 1923, p. 4.

- Селищев, Афанасий. Избранные труды, Москва 1968, с. 580-582.

- Die Slaven in Griechenland von Max Vasmer. Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1941. Kap. VI: Allgemeines und sprachliche Stellung der Slaven Griechenlands, p.324.

- Стойков (Stoykov), Стойко (2002) . Българска диалектология (Bulgarian dialectology) (in Bulgarian). София: Акад. изд. "Проф. Марин Дринов". ISBN 9544308466. OCLC 53429452.

- Institute of Bulgarian Language (1978). Unity of the Bulgarian language in the past and today (Единството на българския език в миналото и днес) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 4. OCLC 6430481.

- Шклифов, Благой. Проблеми на българската диалектна и историческа фонетика с оглед на македонските говори, София 1995, с. 14.

- Шклифов, Благой. Речник на костурския говор, Българска диалектология, София 1977, с. кн. VІІІ, с. 201-205,

- Keith Brown, Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, 1994: From a strictly linguistic point of view Macedonian can be called a Bulgarian dialect, as structurally it is most similar to Bulgarian.

- Colin Baker, Sylvia Prys Jones, Encyclopedia of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education, p. 415: Macedonian is similar to Bulgarian and is sometimes been regarded as a variety of that language.

- Евангелие на Господа Бога и Спаса нашего Иисуса Христо, сига ново типосано на богарской йезик за секоа неделя от година догодина со рет. Преписано и диортосано от мене Павел йероманах, бозигропски протосингел, родом Воденска (Епархия) от село Кониково. Солон, Стампа Кирякова Дарзилен 1852.

- Cousinéry, Esprit Marie. Voyage dans la Macédoine: contenant des recherches sur l'histoire, la géographie, les antiquités de ce pay, Paris, 1831, Vol. II, p. 15-17, one of the passages in English - , Engin Deniz Tanir, The Mid-Nineteenth century Ottoman Bulgaria from the viewpoints of the French Travelers, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University, 2005, p. 99, 142,Kaloudova, Yordanka. Documents on the situation of the population in the southwestern Bulgarian lands under Turkish rule, Военно-исторически сборник, 4, 1970, p. 72

- Pulcherius, Receuil des historiens des Croisades. Historiens orientaux. III, p. 331–a passage in English -http://promacedonia.org/en/ban/nr1.html#4

- Report on the Pomaks, by the Greek Helsinki Monitor

- Who Are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton Indiana UP, 2000 ISBN 0253213592. p. 85, The Interwar period - Greece.

- "Резолюция о македонской нации (принятой Балканском секретариате Коминтерна" - Февраль 1934 г, Москва

- Human Rights Watch

- Greek Helsinki Monitor (Ghm) &

- U.S. ENGLISH Foundation Official Language Research - Greece: Language in everyday life

- Riki Van Boeschoten (2001). Usage des langues minoritaires dans les départements de Florina et d'Aridea (Macédoine) (Use of minority languages in the districts of Florian and Aridea (Macedonia). Strates , Number 10. Villageois et citadins de Grèce (villagers and citizens of Greece), 11 January 2005

- Euromosaic - Le [slavo]macédonien / bulgare en Grèce

- :bg:s:Дописка от село Високо

- Шклифов, Благой and Екатерина Шклифова, Български диалектни текстове от Егейска Македония, София 2003, с. 28-36, 172 (Shkifov, Blagoy and Ekaterina Shklifova. Bulgarian dialect texts from Aegean Macedonia, Sofia 2003, p. 28-36)

- U.S.ENGLISH Foundation Official Language Research - Greece: Language in everyday life

- Lois Whitman (1994): Denying ethnic identity: The Macedonians of Greece Helsinki Human Rights Watch. p.37

- See Ethnologue (); Euromosaic, Le (slavo)macédonien / bulgare en Grèce, L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce, Le valaque/aromoune-aroumane en Grèce, and Mercator-Education: European Network for Regional or Minority Languages and Education, The Turkish language in education in Greece. cf. also P. Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity", in S Barbour, C Carmichael (eds.), Language and nationalism in Europe, Oxford University Press 2000.

- Minority Rights Group,Minorities in the Balkans, page 75.

- Jacques Bacid, Ph.D. Macedonia Through the Ages. Columbia University, 1983.

- GeoNative - Macedonia

- L. M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World 1995, Princeton University Press

- Hill, P. (1999) "Macedonians in Greece and Albania: A Comparative study of recent developments". Nationalities Papers Volume 27, 1 March 1999, page 44(14)

- Poulton, H.(2000), "Who are the Macedonians?",C. Hurst & Co. Publishers

- Readers Digest Encyclopedia of World Geography, 1994, p. 302

- UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile

- UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile

- Eletherotipia article

- Press release of Rainbow

- Historical succes, a Macedonian elected in office in Ovčarani (Meliti)

- Ovčarani proves that Greece is multicultural

- Our language will be heard via radio in Lerin

- Educative and Cultural Movement of Edessa

- In Greece a Macedonian school will open

- ^ Stoyko Stoykov. Bulgarian Dialectology. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Publishing House, 4th Edition, Sofia, 2002, pp. 170–186

- Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.

- Schmieger, R. 1998. "The situation of the Macedonian language in Greece: sociolinguistic analysis", International Journal of the Sociology of Language 131, 125-55.

- стр.247 Граматика на македонскиот литературен јазик, Блаже Конески, Култура- Скопје 1967

- bg:s:Дописка от село Бобища

- Topolinjska, Z. (1998). "In place of a foreword: facts about the Republic of Macedonia and the Macedonian language" in the International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Issue 131

- стр. 244 Македонски јазик за средното образование- Стојка Бојковска, Димитар Пандев, Лилјана Минова-Ѓуркова, Живко Цветковски- Просветно дело- Скопје 2001

- Friedman, V. (2001) Macedonian (SEELRC)

- Poulton, Hugh. (1995). Who Are the Macedonians?, (London: C. Hurst & Co. Ltd:107–108.).

- Z. Topolińska- B. Vidoeski, Polski~macedonski- gramatyka konfrontatiwna, z.1, PAN, 1984

- Friedman, V. (1998) "The implementation of standard Macedonian: problems and results" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Issue 131

- ^ Sussex, Roland (2006). The Slavic Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 509. ISBN 0521223156.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press

- Trudgill, P. (1992) "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe" in International Journal of Applied Linguistics. Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 167–177

- http://www2.mfa.gr/NR/rdonlyres/3E053BC1-EB11-404A-BA3E-A4B861C647EC/0/1923_lausanne_treaty.doc

- Simpson, Neil (1994), Macedonia Its Disputed History, Victoria: Aristoc Press, pp. 101, 102 & 91, ISBN 0646204629

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - In Greece there were Macedonian language schools

- http://edessavoden.gr/

- Македонскиот јазик во Грција се учи тајно како во турско

- Во Грција ќе никне училиште на македонски јазик

- Reprinted Abecedar

- http://florina.org/html/2006/presentation_of_abecedar_in_solun.html

- The Macedonian language in Greece has a stable future

Bibliography

- Trudgill P. (2000) "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity" in Language and Nationalism in Europe (Oxford : Oxford University Press)

- Iakovos D. Michailidis (1996) "Minority Rights and Educational Problems in Greek Interwar Macedonia: The Case of the Primer 'Abecedar'". Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 329-343

External links

| Slavic languages | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||

| East Slavic | |||||||

| South Slavic |

| ||||||

| West Slavic |

| ||||||

| Microlanguages and dialects |

| ||||||

| Mixed languages | |||||||

| Constructed languages | |||||||

| Historical phonology | |||||||

| Italics indicate extinct languages. | |||||||