This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 12.208.143.99 (talk) at 20:43, 23 March 2006 (→Last years). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:43, 23 March 2006 by 12.208.143.99 (talk) (→Last years)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Lenny Bruce (October 13, 1925 – August 3, 1966), born Leonard Alfred Schneider, was a controversial American stand-up comedian and satirist of the 1950s and 1960s.

Overview

Bruce, like his contemporary Mort Sahl, helped change stand-up comedy from the practice of telling jokes to a more daring and experimental form of entertainment. However Bruce was far more daring than Sahl, and tested the limits of convention much more regularly.

His routines took the form of stories, skits, and commentary, often venturing into subject areas considered profane, obscene and otherwise controversial. His penchant for material with high shock value caused his career to be plagued by constant trouble with the law. His obscenity trials are now considered to be significant benchmarks in the case for preservation of First Amendment freedoms.

Bruce was born in Mineola, Long Island, New York, but a chaotic family life in which his parents divorced when he was five, saw him move between relatives over the next decade. His mother, Sally Marr, was a stage performer who would have an enormous influence on Lenny Bruce's career. After spending time working on a farm with a family he saw as providing the stable surroundings he needed, Lenny joined the US Navy at the age of 17 in 1942, and saw active duty in Europe until his discharge in 1946.

After changing his name from Leonard Schneider to Lenny Bruce, he earned $12 and a free spaghetti dinner for his first stand-up performance in Brooklyn, NY. From that modest start, he got his first break as a guest on the Arthur Godfrey Talent Scout Show doing impressions of movie stars. As a "mimic", as these performers were called, Lenny Bruce was not as talented as many of his contemporaries, requiring his act to take a new direction.

In 1951 he was arrested in Miami, Florida, for impersonating a priest. He was soliciting donations for a leper colony in British Guiana after he legally chartered the "Brother Mathias Foundation" (a name of his own invention), and, unknown to the police, stole several priest's clergy shirts and a clerical collar while posing as a laundry man. He was found not guilty due to the legality of the NY state-chartered foundation, the actual existence of the Guiana leper colony, and the inability of local clergy to expose him as an imposter. Later in his semi-fictional autobiography "How to Talk Dirty and Influence People", he revealed that he had made approximately $8,000 in three weeks, sending $2,500 to the leper colony and keeping the rest.

Bruce's early comedy career included writing the screenplays for "Dance Hall Racket" 1953 (which featured Lenny and his wife, Honey Harlow, in roles); "Dream Follies" 1954, a low-budget burlesque romp; and a children's film, "The Rocket Man" 1954. He also released four albums of original material on Berkeley-based Fantasy Records, with rants, comic routines and satirical interviews on the themes that made him famous: jazz, moral philosophy, politics, patriotism, religion, law, race, abortion, drugs, the Ku Klux Klan, Jewishness, and the Roman Catholic Church. These albums were later compiled and re-released as The Lenny Bruce Originals. Two later records were produced and sold by Bruce himself, including a 10" LP of the 1961 San Francisco performances that started his legal troubles. Starting in the late 1960s, other unissued Bruce material was released by Alan Douglas, Frank Zappa and Phil Spector, as well as Fantasy.

His growing fame led to an appearance on the nationally televised Steve Allen Show. On February 3, 1961, in the midst of a severe blizzard, he gave an historic performance at Carnegie Hall in New York. Recorded and later released as a three-disc set, the Carnegie Hall Concert was considered by many to be the zenith of his creative powers; critic Albert Goldman described it as follows:

- "This was the moment that an obscure yet rapidly rising young comedian named Lenny Bruce chose to give one of the greatest performances of his career... The performance contained in this album is that of a child of the jazz age. Lenny worshipped the gods of Spontaneity, Candor and Free Association. He fancied himself an oral jazzman. His ideal was to walk out there like Charlie Parker, take that mike in his hand like a horn and blow, blow, blow everything that came into his head just as it came into his head with nothing censored, nothing translated, nothing mediated, until he was pure mind, pure head sending out brainwaves like radio waves into the heads of every man and woman seated in that vast hall. Sending, sending, sending, he would finally reach a point of clairvoyance where he was no longer a performer but rather a medium transmitting messages that just came to him from out there - from recall, fantasy, prophecy. A point at which, like the practitioners of automatic writing, his tongue would outrun his mind and he would be saying things he didn't plan to say, things that surprised, delighted him, cracked him up - as if he were a spectator at his own performance!"

Legal troubles

In 1961 Bruce was arrested for obscenity at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco; he had used the words cocksucker and to come (for orgasm). Although the jury acquitted him, other communities began monitoring his appearances, resulting in frequent arrests under charges of obscenity. The increased scrutiny also led to an arrest in Philadelphia for drug possession in the same year, and again in Los Angeles, California, two years later.

By the end of 1963, he had become a target of the Manhattan district attorney, Frank Hogan, who was working closely with Francis Cardinal Spellman, the Archbishop of New York. In April, 1964 he appeared twice at the Cafe Au Go Go in Greenwich Village, with undercover police detectives in the audience. On both occasions, he was arrested after leaving the stage, the complaints again resting on his use of various obscenities.

A three-judge panel presided over his widely-publicized six-month-long trial, with Bruce and club owner Howard Solomon being found guilty of obscenity on November 4, 1964. The conviction was announced despite positive testimony and petitions of support from Jules Feiffer, Norman Mailer, William Styron, and James Baldwin, among other artists, writers and educators, as well as Manhattan journalist and television personality Dorothy Kilgallen and sociologist Herbert Gans. Bruce was sentenced on December 21, 1964 to four months in the workhouse; he was set free on bail during the appeals process and died before the appeal was decided. Solomon's conviction was eventually overturned by New York's highest court, the New York Court of Appeals, in 1970.

In 2003 - 37 years after his death - Bruce was granted a pardon by New York governor George Pataki.

Last years

In his later performances, Bruce was known for relating the details of his encounters with the police directly in his comedy routine; his criticism encouraged the police to eye him with maximum scrutiny. These performances often included rants about his court battles over obscenity charges, tirades against fascism and complaints of his denial of his right to free speech.

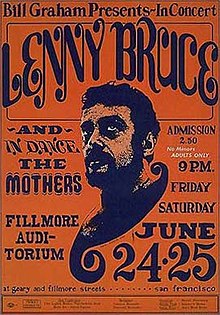

He was banned outright from several U.S. cities, and in 1962 he was banned from performing in Sydney, Australia. At his first show there he got up on stage and declared 'What a fucking wonderful audience' and was promptly arrested. By 1966 he had been blacklisted by nearly every night club in the U.S., as owners feared prosecution for obscenity. His last performance was on June 26, 1966, at the Fillmore in San Francisco, on a bill with Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention.

At the request of Hugh Hefner, Bruce (with the aid of Paul Krassner) wrote his autobiography, which was serialized in Playboy in 1964 and 1965, and later published as the book How to Talk Dirty and Influence People. Hefner, a long-time foe of censorship, had supported Bruce's career, having him on the debut of Playboy's Penthouse in October, 1959.

On August 3, 1966, Lenny Bruce was found dead at the age of 40, from a morphine overdose, in the bathroom of his Hollywood Hills home. He was interred in Eden Memorial Park Cemetery in Mission Hills, California, but an unconventional memorial on August 21 was controversial enough to keep his name in the spotlight. The service saw over 500 people pay their respects, led by legendary record producer Phil Spector. Cemetery officials had attempted to block the ceremony after ads for the event encouraged attendees to bring box lunches and noisemakers.

Bruce was survived by his daughter, Kitty Bruce, who now resides in Pennsylvania. His former wife, Honey Harlow Friedman, lived in Honolulu, Hawaii, until her death on September 12, 2005. His mother, Sally Marr, a comedienne and talent agent, died on December 14, 1997, in Los Angeles, California, aged 91.

Posthumous credits

In 1971 one of his comedy routines was developed by San Francisco filmmaker John Magnuson (who also directed 1967's "Lenny Bruce Performance Film") into a short animated film, Thank You Masked Man (often cited as "Thank You, Mask Man") which parodied The Lone Ranger. Bruce received credit for co-writing and co-directing this seven minute cartoon and providing his unique narration which included all of the voice characterizations.

The 1974 film Lenny, starring Dustin Hoffman, presents a dramatized account of Bruce's life. Eddie Izzard portrayed the comedian in the 1999 production of Julian Barry's 1971 play Lenny. Similarly, the comedian inspired or was mentioned in songs by Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Nico, Chumbawamba, The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, R.E.M., Metric, Steve Earle, Simon and Garfunkel, Tim Hardin (who lived in Bruce's house for a time), Grace Slick (whose "Father Bruce" with the Great Society was written while Bruce was alive, celebrating his surviving a fall from a San Francisco hotel window in 1965) and Genesis.

The 1998 documentary Lenny Bruce: Swear To Tell the Truth, written and directed by Robert B. Weide, was nominated for an Oscar. Robert De Niro provided the narration.

In response to a petition prepared by Robert Corn-Revere and filed by Ron Collins and David Skover, on December 23, 2003, Lenny Bruce was posthumously pardoned by New York Republican Governor George Pataki for the obscenity conviction arising from his 1964 New York performances in the Cafe Au Go Go. It was the first posthumous pardon in the state's history. Pataki called his decision "a declaration of New York's commitment to upholding the First Amendment."

In 2004, Bruce was voted #3 of the "100 Greatest Standup Comedians of All Time" by Comedy Central behind Richard Pryor and George Carlin, both of whom cite Bruce as an influence (Carlin was arrested as an audience member for refusing to show an ID at Bruce's 1964 show at the Gate of Horn in Chicago, after the police stopped the show and arrested Bruce for obscenity). He was also the subject of a six CD retrospective entitled Let The Buyer Beware, overseen by record producer Hal Willner.

Books by or about Bruce

- Lenny Bruce "Stamp Help Out!" (1961 and/or 1965, self-published and sold at his concerts and in hip bookshops like City Lights in SF)

- Lenny Bruce, How to Talk Dirty & Influence People (Playboy Publishing, 1967)

- The Essential Lenny Bruce, compiled and edited by John Cohen (Ballantine Books, 1967)

- Albert Goldman, with Lawrence Schiller, Ladies and Gentlemen: Lenny Bruce!! (Random House, 1971)

- Ronald Collins & David Skover, The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall & Rise of an American Icon (Sourcebooks, 2002)

- Frank Kofsky, Lenny Bruce: The Comedian as Social Critic & Secular Moralist (Monad Press, 1974)

- Julian Barry, Lenny (play)(Grove Press, Inc. 1971)

- Valerie Kohler Smith, "Lenny" (based on Barry play) (Grove Press, Inc., 1974)

- Kitty Bruce "The (almost) Unpublished Lenny Bruce" (1984, Running Press) (includes a graphically spruced up reproduction of "Stamp Help Out!")

- William Karl Thomas, Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet (Archon Books, 1989)

- Don De Lillo, "Underworld", (Simon and Schuster Inc., 1997)

External links

- Lenny Bruce - kirjasto.sci.fi

- The Lenny Bruce FBI File

- Lenny Bruce - Ubqtous.com

- The Complete Lenny Bruce

- The Trials of Lenny Bruce

- Lenny Bruce: Swear To Tell the Truth, Sundance Channel's summary of the documentary

- Background on Swear To Tell the Truth, from its writer/director, who was separately interviewed about the project

- The Lenny Bruce Trial