This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Cedrus-Libani (talk | contribs) at 20:29, 7 April 2006 (Reverted edits by Cedar-Guardian (talk) to last version by Circeus). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:29, 7 April 2006 by Cedrus-Libani (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by Cedar-Guardian (talk) to last version by Circeus)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Yom Kippur War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab-Israeli conflict | |||||||

| File:Yom Kippur War 2.jpg "Israeli paratroops breaking through an Egyptian commando ambush on a sandspit leading to Fort Budapest on the Sinai front" (Rabinovich, 278) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Israel |

Egypt, Syria, (Jordan, Iraq) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Moshe Dayan, David Elazar, Ariel Sharon, Shmuel Gonen, Benjamin Peled |

Saad El Shazly, Ahmad Ismail Ali | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 415,000 troops; 1,500 tanks, 3,000 armored carriers; 945 artillery units 100 mm and up; 561 airplanes, 84 helicopters; 38 warships. |

Egypt: 830,000 troops; 2,200 tanks, 2,400 armored carriers; 1,120 artillery units 100 mm and up; 690 airplanes, 161 helicopters; 104 warships Syria: 332,000 troops; 1,350 tanks, 1,300 armored carriers; 655 artillery units 100 mm and up; 321 airplanes, 36 helicopters; 21 warships Iraq: 20,000 troops, 310 tanks, 300 armored carriers, 54 artillery units, 73 airplanes) See also Other participants | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,656 killed 7,250 wounded 400 tanks destroyed 600 damaged/returned to service 102 planes shot down (Rabinovich, 496–497) |

8,528 killed 19,540 wounded (Western analysis) 15,000 dead 35,000 wounded (Israeli analysis) 2,250 tanks destroyed or captured 432 planes destroyed (Rabinovich, 496–497) | ||||||

The Yom Kippur War, Ramadan War or October War (Hebrew: מלחמת יום הכיפורים; transliterated: Milkhemet Yom HaKipurim or מלחמת יום כיפור Milkhemet Yom Kipur; Arabic: حرب أكتوبر; transliterated: Harb October or حرب تشرين transliterated: Harb Tishrin), also known as the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, was fought from October 6 to October 26 1973, between Israel and a coalition of Arab nations led by Egypt and Syria. The war began on the day of Yom Kippur with a surprise joint attack by Egypt and Syria. They invaded the Sinai and Golan Heights, respectively, which had been captured by Israel in 1967 during the Six-Day War.

The Egyptians and Syrians advanced during the first 24–48 hours, after which momentum began to swing in Israel's favor. By the second week of the war, the Syrians had been pushed entirely out of the Golan Heights. In the Sinai to the south, the Israelis had struck at the "hinge" between two invading Egyptian armies, crossed the Suez Canal (where the old cease-fire line had been), and cut off an entire Egyptian army just as a United Nations cease-fire came into effect.

The war had far-reaching implications for many nations. The Arab world, which had been humiliated by the lopsided defeat of the Egyptian-Syrian-Jordanian alliance during the Six-Day War, felt psychologically vindicated by its string of victories early in the conflict. This vindication paved the way for the peace process that followed, as well as liberalizations such as Egypt's infitah policy. The Camp David Accords which came soon after led to normalized relations between Egypt and Israel—the first time any Arab country had recognized the Israeli state. Egypt, which had already been drifting away from the Soviet Union, then left the Soviet sphere of influence almost entirely.

Background

Casus belli

Template:Campaignbox Arab-Israeli conflict This war was part of the Arab-Israeli conflict, a conflict which has included many battles and wars since 1948. During the Six-Day War six years earlier, the Israelis had captured the Sinai clear to the Suez Canal, which had become the cease-fire line. The Israelis had also captured roughly half of the Golan Heights from Syria.

In the years following that war, Israel erected lines of fortification in both the Sinai and the Golan Heights. In 1971 Israel spent $500 million fortifying its positions on the Suez Canal, a chain of fortifications and gigantic earthworks known as the Bar Lev Line, named after Israeli General Chaim Bar-Lev.

Egypt and Syria both desired a return of the land lost in the Six-Day War. However, victory in that war as well as the three-year-long War of Attrition had left the Israeli leadership confident in its grip on these territories and therefore reluctant to negotiate their return.

Nonetheless, according to Chaim Herzog,

- On June 19 1967, the National Unity Government voted unanimously to return the Sinai to Egypt and the Golan Heights to Syria in return for peace agreements. The Golans would have to be demilitarized and special arrangement would be negotiated for the Straits of Tiran. The government also resolved to open negotiations with King Hussein of Jordan regarding the Eastern border.

Later, the Khartoum Arab Summit resolved that there would be "no peace, no recognition and no negotiation with Israel."

President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt died in September 1970. He was succeeded by Anwar Sadat, who resolved to fight Israel and win back the territory lost in the Six-Day War. In 1971, Sadat, in response to an initiative by UN intermediary Gunnar Jarring, declared that if Israel committed itself to "withdrawal of its armed forces from Sinai and the Gaza Strip" and to implementation of other provisions of UN Security Council Resolution 242 as requested by Jarring, Egypt would then "be ready to enter into a peace agreement with Israel." Israel responded that it would not withdraw to the pre-June 5 1967 lines.

Sadat hoped that by inflicting even a limited defeat on the Israelis, the status quo could be altered. Hafiz al-Assad, the head of Syria, had a different view. He had little interest in negotiation and felt the retaking of the Golan Heights would be a purely military option. Since the Six-Day War, Assad had launched a massive military build up and hoped to make Syria the dominant military power of the Arab states. With the aid of Egypt, Assad felt that his new army could win convincingly against the Israeli army and thus secure Syria's role in the region. Assad only saw negotiations beginning once the Golan Heights had been retaken by force, which would induce Israel to give up the West Bank and Gaza, and make other concessions.

Sadat also had important domestic concerns in wanting war. "The three years since Sadat had taken office… were the most demoralized in Egyptian history… A desiccated economy added to the nation's despondency. War was a desperate option." (Rabinovich, 13). In his biography of Sadat, Raphael Israeli argued that Sadat felt the root of the problem was in the great shame over the Six-Day War, and before any reforms could be introduced he felt that shame had to be overcome. Egypt's economy was in shambles, but Sadat knew that the deep reforms that he felt were needed would be deeply unpopular among parts of the population. A military victory would give him the popularity he needed to make changes. A portion of the Egyptian population, most prominently university students who launched wide protests, strongly desired a war to reclaim the Sinai and were highly upset that Sadat had not launched one in his first three years in office.

The other Arab states showed much more reluctance to fully commit to a new war. King Hussein of Jordan feared another major loss of territory as had occurred in the Six-Day War, during which Jordan was halved in population. Sadat was also backing the claim of the PLO to the territories (West Bank and Gaza) and in the event of a victory promised Yasser Arafat that he would be given control of them. Hussein still saw the West Bank as part of Jordan and wanted it restored to his kingdom. Moreover, during the Black September crisis of 1970 a near civil war had broken out between the PLO and the Jordanian government. In that war Syria had intervened militarily on the side of the PLO, leaving Assad and Hussein estranged.

Iraq and Syria also had strained relations, and the Iraqis refused to join the initial offensive. Lebanon, which shared a border with Israel, was not expected to join the Arab war effort due to its small army and already evident instability. The months before the war saw Sadat engage in a diplomatic offensive to try to win support for the war. By the fall of 1973 he claimed the backing of more than a hundred states. These were most of the countries of the Arab League, Non-Aligned Movement, and Organization of African Unity. Sadat had also worked to curry favour in Europe and had some success before the war. Britain and France had for the first time sided with the Arab powers against Israel on the United Nations Security Council. In the lead up to the war West Germany became one of Egypt's largest sources of materiel.

Events leading up to the war

Anwar Sadat in 1972 publicly stated that Egypt was committed to going to war with Israel, and that they were prepared to "sacrifice one million Egyptian soldiers." From the end of 1972, Egypt began a concentrated effort to build up its forces, receiving MiG-23s, SA-6s, RPG-7s, T-62 Tanks, and especially the AT-3 Sagger anti-tank guided missile from the Soviet Union and improving its military tactics. Political generals, who had in large part been responsible for the rout in 1967, were replaced with competent ones.

The role of the great powers, too, was a major factor in the outcome of the two wars. The policy of the Soviet Union was one of the causes of Egypt's military weakness. While the U.S. and other allied nations supplied Israel with the most up-to-date assault weapons in the world, the Russians supplied Egypt only with defensive weaponry, and then only with great reluctance. Indeed, President Nasser was only able to obtain the material for an anti-aircraft missile defense wall after visiting Moscow and pleading with the Kremlin leaders. He claimed that if supplies were not given, he would have to return to Egypt and tell the Egyptian people Moscow had abandoned them, and then relinquish power to one of his peers who would be able to deal with the Americans. The Americans would then have the upper hand in the region, which Moscow could not permit.

One of Egypt's undeclared objectives of the War of Attrition was to force the Soviet Union to supply Egypt with more advanced arms and war materiel. Egypt felt the only way to convince the Soviet leaders of the deficiencies of most of the aircraft and air defense weaponry supplied to Egypt following 1967 was to put the Soviet weapons to the test against the advanced weaponry the United States supplied to Israel.

Nasser's policy following the 1967 defeat conflicted with that of the Soviet Union. The Soviets sought to push Egypt towards a peaceful solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. At all costs they wanted to avoid a new conflagration between the Arabs and Israelis so as not to be drawn into a confrontation with the United States. The reality of the situation became apparent when the superpowers met in Oslo and agreed to maintain the status quo. This was unacceptable to Egyptian leaders, and when it was discovered that the Egyptian preparations for crossing the canal were being leaked, it became imperative to expel the Russians from Egypt. In July 1972 Sadat expelled almost all of the 20,000 Soviet military advisors in the country and reoriented the country's foreign policy to be more favorable to the United States.

The Soviets thought little of Sadat's chances in any war. They warned that any attempt to cross the heavily fortified Suez would incur massive losses. The Soviets, who were then pursuing Detente, had no interest in seeing the Middle East destabilized. In a June 1973 meeting with U.S. President Richard Nixon, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev had proposed Israel pull back to its 1967 border. Brezhnev said that if Israel did not, "we will have difficulty keeping the military situation from flaring up"—an indication that the Soviet Union had been unable to restrain Sadat's plans (Rabinovich, 39).

In an interview published in Newsweek (April 9 1973), President Sadat again threatened war with Israel. Several times during 1973, Arab forces conducted large-scale exercises that put the Israeli military on the highest level of alert, only to be recalled a few days later. The Israeli leadership already believed that if an attack took place, the Israeli Air Force would be able to repel it.

Almost a full year before the war, in an October 24, 1972, meeting with his Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, Sadat declared his intention to go to war with Israel even without proper Soviet support (Rabinovich, 25). Planning was done in absolute secrecy—even the upper-echelon commanders were not told of war plans until less than a week prior to the attack, and the soldiers were not told until a few hours beforehand. The plan to attack Israel in concert with Syria was code-named Operation Badr (the Arabic word for "full moon").

Lead up to the surprise attack

The IDF's Aman, or military intelligence, "the leader of Israel's intelligence community," was responsible for formulating the nation's intelligence estimate (Rabinovich, 22). Their assessments on the likelihood of war were based on several assumptions. First, it was assumed correctly that Syria would not go to war with Israel unless Egypt went to war as well. Second, they learned from a high-ranking Egyptian informant (who remains confidential to this day, known only as "The Source") that Egypt wanted to regain all of the Sinai, but would not go to war until the Soviets had supplied Egypt with fighter-bombers to neutralize the Israeli Air Force, and Scud missiles to be used against Israeli cities as a deterrent against Israeli attacks on Egyptian infrastructure. Since the Soviets had not yet supplied the fighter bombers, and the Scud missiles had only arrived in Egypt in late August, and in addition it would take 4 months to train the Egyptian ground crews, Aman predicted war with Egypt was not imminent. This assumption about Egypt's strategic plans, known as "the concept," strongly prejudiced their thinking and led them to dismiss other war warnings.

The Egyptians did much to further this misconception. Both the Israelis and the Americans felt that the expulsion of the Soviet military observers had severely hurt the army. The Egyptians ensured that there was a continual stream of false information on maintenance problems and a lack of personnel to operate the most advanced equipment. The Egyptians made repeated misleading reports about lack of spare parts that also made their way to the Israelis. Sadat had so long engaged in brinkmanship, that his frequent war threats were being ignored by the world. In May and August 1973 the Egyptian army had engaged in exercises by the border and moblizing in response both times had cost the Israeli army of some $10 million.

For the week leading up to Yom Kippur, the Egyptians staged a week-long training exercise adjacent to the Suez Canal. Israeli intelligence, detecting large troop movements towards the canal, dismissed these movements as more training exercises. Movements of Syrian troops towards the border was puzzling, but not a threat because, Aman believed, they would not attack without Egypt and Egypt would not attack until the Soviet weaponry arrived.

The obvious reason for choosing the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur for staging a surprise attack on Israel was that on this specific day (unlike any other holiday) the country comes to a complete standstill. On Yom Kippur, not only observant, but most secular Jews fast, abstain from any use of fire, electricity, engines, communications, etc., and all road traffic comes to a standstill. Many soldiers leave military facilities for home during the holiday and Israel is most vulnerable, especially with much of its army demobilized.

Despite refusing to participate, King Hussein of Jordan "had met with Sadat and Assad in Alexandria two weeks before. Given the mutual suspicions prevailing among the Arab leaders, it was unlikely that he had been told any specific war plans. But it was probable that Sadat and Assad had raised the prospect of war against Israel in more general terms to feel out the likelihood of Jordan joining in" (Rabinovich, 51). On the night of September 25, Hussein secretly flew to Tel Aviv to warn Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir of an impending Syrian attack. "Are they going to war without the Egyptians, asked Mrs. Meir. The king said he didn't think so. 'I think they would cooperate'". (Rabinovich, 50) Surprisingly, this warning fell on deaf ears. Aman concluded that the king had not told it anything it did not already know. "Eleven warnings of war were received by Israel during September from well placed sources. But Zvi Zamir continued to insist that war was not an Arab option. Not even Hussein's warnings succeeded in stirring his doubts" (Rabinovich, 56). He would later remark that "We simply didn't feel them capable " (Rabinovich, 57).

Finally, Zvi Zamir personally went to Europe to meet with The Source (the high-ranking Egyptian official), at midnight on October 5th/6th. At that meeting, the source informed him that a joint Syrian-Egyptian attack on Israel was imminent. It was this warning in particular, combined with the large number of other warnings, that finally goaded the Israeli high command into action. Just hours before the attack began, orders went out for a partial call-up of the Israeli reserves. Ironically, calling up the reserves proved to be easier than usual, as almost all of the troops were at synagogue or at home for the holiday.

Lack of an Israeli pre-emptive attack

The Israeli strategy was, for the most part, based on the precept that if war was imminent, Israel would launch a pre-emptive strike. It was assumed that Israel's intelligence services would give, at the worst case, about 48 hours notice prior to an Arab attack.

Golda Meir, Moshe Dayan, and Israeli general David Elazar met at 8:05] the morning of Yom Kippur, 6 hours before the war was to begin. Dayan began the meeting by arguing that war was not a certainty. Elazar then presented his argument, in favor of a pre-emptive attack against Syrian airfields at noon, Syrian missiles at 3:00Template:PM, and Syrian ground forces at 5:00Template:PM. "When the presentations were done, the prime minister hemmed uncertainly for a few moments but then came to a clear decision. There would be no preemptive strike. Israel might be needing American assistance soon and it was imperative that it not be blamed for starting the war. 'If we strike first, we won't get help from anybody', she said" (Rabinovich, 89). European nations, under threat of an Arab oil embargo and trade boycott, had stopped supplying Israel with munitions. As a result, Israel was totally dependent on the United States to resupply its army, and was particularly sensitive to anything that might endanger that relationship.

In retrospect, the decision not to strike was probably a sound one. While Operation Nickel Grass, the American airlift of supplies during the war which began October 13, did not immediately replace Israel's losses in equipment, it did allow Israel to expend what it did have more freely (Rabinovich, 491). Had they struck first, according to Henry Kissinger, they would not have received "so much as a nail".

Combat Operations

In the Sinai

The Egyptian units would not advance beyond a shallow strip for fear of losing protection of their SAM missile batteries. In the Six-Day War, the Israeli Air Force had pummelled the defenseless Arab armies. Egypt (and Syria) had heavily fortified their side of the cease-fire lines with SAM batteries, against which the Israeli Air Force had no effective countermeasures. Israel, which had invested much of its defense budget building the region's strongest air force, would see its air force rendered almost useless by the presence of the SAM batteries.

Anticipating a swift Israeli armored counterattack, the Egyptians had armed their first wave with unprecedented numbers of man-portable anti-tank weapons—Rocket propelled grenades and the more devastating Sagger missiles. One in every three Egyptian soldiers had an anti-tank weapon. "Never before had such intensive anti-tank fire been brought to bear on the battlefield" (Rabinovich, 108). In addition, the ramp on the Egyptian side of the canal had been increased to twice the height of the Israeli ramp, giving them an excellent vantage point from which to fire down on the Israelis, as well as any approaching tanks.

The Egyptian army surprised many by breaching the Israeli defenses (which were undermanned due to Yom-Kippur) and quickly crossing the Suez Canal in what became known as The Crossing, reducing all but one of the Bar-Lev forts. In a meticulously rehearsed operation, the Egyptian forces advanced approximately 15 km into the Sinai desert with the combined forces of two army corps. The Israelis had set up defensive positions behind huge sand berms on the east bank of the canal, which experience taught them would be nearly impervious to bombing or artillery attack. However, Egyptian military engineers came up with an ingenious plan—attacking the berms with water cannon, fed directly from the canal. The berms disintegrated under water pressure, leaving the Israeli defensive positions exposed.

The Israeli battalion garrisoning the Bar-Lev forts was outnumbered by an order of 100 to 1, and was overwhelmed. Only one fortification, code named Budapest (the northernmost Bar-Lev fort), would remain in Israeli control through the end of the war.

The Egyptian forces consolidated their initial positions. On October 8, Shmuel Gonen, commander of the Israeli Southern front—who had only taken the position 3 months before at the retirement of Ariel Sharon—ordered a counterattack by Gabi Amir's brigade against entrenched Egyptian forces at Hizayon, where approaching tanks could be easily destroyed by Saggers fired from the Egyptian ramp. Despite Amir's reluctance, the attack proceeded, and the result was a disaster for the Israelis. Towards nightfall, a counterattack by the Egyptians was stopped by Ariel Sharon's division—Sharon had been reinstated as a division commander at the outset of the war. The fighting lulled, with neither side wanting to mount a large attack against the other.

Following the disastrous Israeli attack on the 8th, both sides settled into defensive postures and hoped for the other side to attack (Rabinovich, 353). Elazar replaced Gonen, who had proven out-of-his-league, with Haim Bar-Lev, who had come out of retirement. Because it was considered dangerous to morale to replace the front commander during the middle of a battle, rather than being sacked Gonen was made chief-of-staff to the newly appointed Bar-Lev.

After several days of waiting, Sadat, wanting to ease pressure on the Syrians, ordered his chief generals (Saad El Shazly and Ahmad Ismail Ali chief among them) to attack. The Egyptian forces brought across their reserves and began their counterattack on 14 October. "The attack, the most massive since the initial Egyptian assault on Yom Kippur, was a total failure, the first major Egyptian reversal of the war. Instead of concentrating forces of maneuvering, except for the wadi thrust, they had expended them in head-on attack against the waiting Israeli brigades. Egyptian losses for the day were estimated at between 150 and 250 tanks" (Rabinovich, 355)

The following day, October 15, the Israelis launched Operation Stouthearted Men—the counterattack against the Egyptians and crossing of the Suez Canal. The attack was a tremendous change of tactics for the Israelis, who had previously relied on air and tank support—support that had been decimated by the well-prepared Egyptian forces. Instead, the Israelis used infantry to infiltrate the positions of the Egyptian SAM and anti-tank batteries, which were unable to cope as well with forces on foot. A division led by Major General Ariel Sharon attacked the Egyptian line just north of Bitter Lake, in the vicinity of Ismailiya. The Israelis struck at a weak point in the Egyptian line, the "seam" between the Egyptian second Army in the north and the Egyptian third Army in the south. In some of the most brutal fighting of the war in and around the Chinese Farm (an irrigation project east of the canal and north of the crossing point), the Israelis opened a hole in the Egyptian line and reached the Suez Canal. A small force crossed the canal and created a bridgehead on the other side. For over 24 hours, troops were ferried across the canal in light inflatable boats, with no armor support of their own. They were well supplied with American-made M72 LAW rockets, negating the threat of Egyptian armor. Once the anti-aircraft and anti-tank defences of the Egyptians had been neutralized, the infantry once again was able to rely on overwhelming tank and air support.

Prior to the war, fearing an Israeli crossing of the canal, no Western nation would supply the Israelis with bridging equipment. They were able to purchase and repair modular, pontoon bridging equipment from a French WWII scrap lot. The Israelis also constructed a rather sophisticated indigenous "roller bridge" but logistical delays involving heavy congestion on the roads leading to the crossing point delayed its arrival to the canal for several days. Deploying the pontoon bridge on the night of October 16/17, Avraham "Bren" Adan's division crossed and raced south, intent on cutting off the Egyptian third Army before it could retreat west back into Egypt. At the same time, it sent out raiding forces to destroy Egyptian SAM missile batteries east of the canal. By October 19 the Israelis managed to construct four separate bridges just north of the Great Bitter Lake under heavy Egyptian bombardment. By the end of the war the Israelis were well within Egypt, reaching a point 101 kilometers from its capital, Cairo.

On the Golan Heights

In the Golan Heights, the Syrians attacked the Israeli defenses of two brigades and eleven artillery batteries with five divisions and 188 batteries. At the onset of the battle, approximately 180 Israeli tanks faced off against approximately 1,400 Syrian tanks. Every Israeli tank deployed on the Golan Heights was engaged during the initial attacks. Syrian commandos dropped by helicopter also took the most important Israeli stronghold at Jabal al Shaikh (Mount Hermon), which had a variety of surveillance equipment.

Fighting in the Golan Heights was given priority by the Israeli High Command. The fighting in the Sinai was sufficiently far away that Israel was not immediately threatened; should the Golan Heights fall, the Syrians could easily advance into Israel itself. Reservists were directed to the Golan as quickly as possible. They were assigned to tanks and sent to the front as soon as they arrived at army depots, without waiting for the crews they trained with to arrive, without waiting for machine guns to be installed on their tanks, and without taking the time to calibrate their tank guns (a time-consuming process known as bore-sighting).

As the Egyptians had in the Sinai, the Syrians on the Golan Heights took care to stay under cover of their SAM missile batteries. Also as in the Sinai, the Syrians made use of Soviet anti-tank weapons (which, because of the uneven terrain, were not as effective as in the flat Sinai desert).

The Syrians had expected it would take at least 24 hours for Israeli reserves to reach the front lines; in fact, Israeli reserve units began reaching the battle lines only fifteen hours after the war began.

By the end of the first day of battle, the Syrians (who at the start outnumbered the Israelis in the Golan 9 to 1) had achieved moderate success. Towards the end of the day, "A Syrian tank brigade passing through the Rafid Gap turned northwest up a little-used route known as the Tapline Road, which cut diagonally across the Golan. This roadway would prove one of the main strategic hinges of the battle. It led straight from the main Syrian breakthrough points to Nafah, which was not only the location of Israeli divisional headquarters but the most important crossroads on the Heights." During the night, Lieutenant Zvika Greengold, who had just arrived to the battle unattached to any unit, fought them off with his single tank until help arrived. "For the next 20 hours, Zvika Force, as he came to be known on the radio net, fought running battles with Syrian tanks—sometimes alone, sometimes as part of a larger unit, changing tanks half a dozen times as they were knocked out. He was wounded and burned but stayed in action and repeatedly showed up at critical moments from an unexpected direction to change the course of a skirmish." . For his actions, Zvika became a national hero in Israel.

During over four days of fighting, the Israeli 7th Armored Brigade in the north (commanded by Yanush Ben Gal) managed to hold the rocky hill line defending the northern flank of their headquarters in Nafah. For some as-yet-unexplained reason, the Syrians were close to conquering Nafah, yet they stopped the advance on Nafah's fences, letting Israel assemble a defensive line. The most reasonable explanation for this is that the Syrians had precalculated estimated advances, and the commanders in the field didn't want to digress from the plan. To the south, however, the Barak Armored Brigade, bereft of any natural defenses, began to take on heavy casualties. Brigade Commander Colonel Shoham was killed during the second day of fighting, along with his Second in Command and their Operations Officer (each in a separate tank) as the Syrians desperately tried to push inwards towards the Sea of Galilee and towards Nafah. At this point the Brigade stopped functioning as a cohesive force, although the remaining tanks and crewmen continued fighting independently.

The tide in the Golan turned as the arriving Israeli reserve forces were able to contain and, starting 8 October, push back the Syrian offensive. The tiny Golan Heights were too small to act as an effective territorial buffer, unlike the Sinai Peninsula in the south, but it proved to be a strategic geographical stronghold and was a crucial key in preventing the Syrian army from bombing the cities below. By Wednesday, October 10, the last Syrian unit in the Central sector had been pushed back across the purple line, that is, the pre-war border (Rabinovich, 302).

A decision now had to be made—whether to ease the fighting down and end the war at the 1967 border, or to continue the war into Syrian territory. Israeli High Command spent the entire October 10 debating this, well into the night. Some favored disengagement, which would allow soldiers to be redeployed to the Sinai (Shmuel Gonen's ignominious defeat at Hizayon in the Sinai had happened two days earlier). Others favored continuing the attack into Syria, towards Damascus, which would knock Syria out of the war; it would also restore Israel's image as the supreme military power in the Middle East and would give them a valuable bargaining chip once the war ended. Others countered that Syria had strong defenses—antitank ditches, minefields, and strongpoints—and that it would be better to fight from defensive positions in the Golan Heights (rather than the flat terrain of Syria) in the event of another war with Syria. However, Prime Minister Meir realized the most crucial point of the whole debate—"It would take four days to shift a division to the Sinai. If the war ended during this period, the war would end with a territorial loss for Israel in the Sinai and no gain in the north—an unmitigated defeat. This was a political matter and her decision was unmitigating—to cross the purple line… The attack would be launched tomorrow, Thursday, October 11" (Rabinovich, 304).

From 11 October to 14 October, the Israeli forces pushed into Syria, conquering a further twenty-square-mile box of territory in the Bashan. From there they were able to shell the outskirts of Damascus, only 40 km away, using heavy artillery.

"As Arab position on the battlefields deteriorated, pressure mounted on King Hussein to send his Army into action. He found a way to meet these demands without opening his kingdom to Israeli air attack. Instead of attacking Israel from their common border, he sent an expeditionary force into Syria. He let Israel know of his intentions, through US intermediaries, in the hope that it would accept that this was not a casus belli justifying an attack into Jordan… Dayan declined to offer any such assurance, but Israel had no intention of opening another front" (Rabinovich, 433).

Iraq also sent an expeditionary force to the Golan, consisting of some 30,000 men, 500 tanks, and 700 APCs (Rabinovich, 314). The Iraqi divisions were actually a strategic surprise for the IDF, which expected a 24-hour-plus advance intelligence of such moves. This turned into an operational surprise, as the Iraqis attacked the exposed southern flank of the advancing Israeli armor, forcing its advance units to retreat a few kilometers, in order to prevent encirclement.

Combined Syrian, Iraqi and Jordanian counterattacks prevented any further Israeli gains. However, they were also unable to push the Israelis back from their Bashan salient.

On 22 October, the Golani Brigade and Sayeret Matkal commandos recaptured the outpost on Mount Hermon, after sustaining very heavy casualties from entrenched Syrian snipers strategically positioned on the mountain. An attack two weeks before had cost 25 dead and 67 wounded, while this second attack cost an additional 55 dead and 79 wounded (Rabinovich, 450). An Israeli D9 bulldozer with Israeli infantry breached a way to the peak, preventing the peak from falling into Syrian hands after the war. A paratrooper brigade took the corresponding Syrian outposts on the mountain.

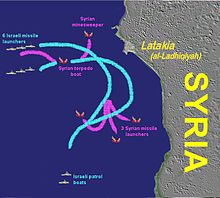

At sea

The Battle of Latakia, a revolutionary naval battle between the Syrians and the Israelis, took place on October 7, the second day of the war, resulting in a resounding Israeli victory that proved the potency of small, fast missile boats equipped with advanced ECM packages. This battle was the world's first battle between missile boats equipped with surface-to-surface missiles. The battle also established the Israeli Navy, long derided as the "black sheep" of the Israeli services, as a formidable and effective force in its own right. Following this and other smaller naval battles, the Syrian and Egyptian navies stayed at their Mediterranean Sea ports throughout most of the war, enabling the Mediterranean sea lanes to Israel to remain open. This enabled uninterrupted resupply of the IDF by American ships (96% of all resupply tonnage was shipborne, not airlifted, contrary to public perception).

However, the Israeli navy was less successful in breaking the Egyptian Navy's blockade of the Red Sea for Israeli or Israel-bound shipping, thus hampering Israel's oil resupply via the port of Eilat. Israel did not possess enough missile boats in Red Sea ports to enable breaking the blockade, a fact it regretted in hindsight.

Several other times during the war, the Israeli navy mounted small assault raids on Egyptian ports. Both Fast Attack Craft and Shayetet 13 naval commandos were active in these assaults. Their purpose was to destroy boats that were to be used by the Egyptians to ferry their own commandos behind Israeli lines. The overall effect of these raids on the war was relatively minor.

Participation by other states

Besides Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq, several other Arab nations were involved in this war, providing additional weapons and financing. The amount of support is uncertain.

Saudi Arabia and Kuwait gave financial aid and sent some token forces to join in the battle. Morocco sent three brigades to the front lines; the Palestinians sent troops as well (Rabinovich, 464). Pakistan sent sixteen pilots.

From 1971 to 1973, Muammar al-Qaddafi of Libya sent Mirage fighters and gave Egypt around $1 billion to arm for war. Algeria sent squadrons of fighters and bombers, armored brigades, and dozens of tanks. Tunisia sent over 1,000 soldiers, who worked with Egyptian forces in the Nile delta, and Sudan sent 3,500 soldiers.

Uganda radio reported that Idi Amin sent Ugandan soldiers to fight against Israel. Cuba also sent approximately 1,500 troops including tank and helicopter crews who reportedly also engaged in combat operations against the IDF.

Armaments

The Arab armies were equipped with predominantly Soviet-made weapons while Israel's armaments were mostly Western-made. It should be noted that the Arab army's T-62 were equipped with night vision equipment that the Israeli armoured forces lacked - giving them an added advantage on the battlefield.

| Type | Arab armies | IDF |

|---|---|---|

| Tanks | T-54 and T-55, T-62, T-34 and PT-76 | Sherman, Patton, Centurion, AMX, also about 200 of T-54, T-55 and PT-76 taken as trophies |

| Airplanes | MiG-21, MiG-19, MiG-17, Su-7B, Tu-16, Il-28, Il-18, Il-14, An-12 | A-4 Skyhawk, F-4 Phantom II, Dassault Mirage III, Dassault Mystère IV, IAI Nesher, Sud Aviation Vautour |

| Helicopters | Mi-6, Mi-8 | Super Frelon, CH-53, S-58, AB-205, MD500 Defender |

The cease-fire and immediate aftermath

Egypt's trapped Third Army

The United Nations passed a cease-fire, largely negotiated between the U.S. and Soviet Union, on October 22. It called for an end to the fighting between Israel and Egypt (but technically not between Syria and Israel). It came into effect 12 hours later at 6:52Template:PM Israeli time. (Rabinovich, 452). Because it went into effect after darkness, it was impossible for satellite surveillance to determine where the front lines were when the fighting was supposed to stop (Rabinovich, 458).

When the cease-fire began, the Israeli forces were just a few hundred meters short of their goal—the last road linking Cairo and Suez. During the night, the Egyptians broke the cease-fire in a number of locations, destroying nine Israeli tanks. In response, David Elazar requested permission to resume the drive south, and Moshe Dayan approved (Rabinovich, 463). The Israeli troops finished the drive south, captured the road, and trapped the Egyptian Third Army east of the Suez Canal.

The next morning, October 23, a flurry of diplomatic activity occurred. Soviet reconnaissance flights had confirmed that Israeli forces were moving south, and the Soviets accused the Israelis of treachery. In a phone call with Golda Meir, Henry Kissinger asked, "how can anyone ever know where a line is or was in the desert?" Meir responded, "they'll know, all right." Kissinger found out about the trapped Egyptian army shortly thereafter. (Rabinovich, 465).

Kissinger realized the situation presented the United States with a tremendous opportunity—Egypt was totally dependent on the United States to prevent Israel from destroying its trapped army, which now had no access to food or water. The position could be parlayed later into allowing the United States to mediate the dispute, and push Egypt out of Soviet influences.

As a result, the United States exerted tremendous pressure on the Israelis to refrain from destroying the trapped army, even threatening to support a UN resolution to force the Israelis to pull back to their October 22 positions if they did not allow non-military supplies to reach the army. In a phone call with Israeli ambassador Simcha Dinitz, Kissinger told the ambassador that the destruction of the Egyptian Third Army "is an option that does not exist" (Rabinovich, 487).

Nuclear alert

In the meantime, Brezhnev sent Nixon a letter in the middle of the night of October 23–24. In that letter, Brezhnev proposed that American and Soviet contingents be dispatched to ensure both sides honor the cease-fire. He also threatened that "I will say it straight that if you find it impossible to act jointly with us in this matter, we should be faced with the necessity urgently to consider taking appropriate steps unilaterally. We cannot allow arbitrariness on the part of Israel" (Rabinovich, 479). In short, the Soviets were threatening to intervene in the war on Egypt's side.

The message arrived after Nixon had gone to bed. Kissinger immediately called a meeting of senior officials, including Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, CIA Director William Colby, and White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig. The Watergate scandal had reached its apex, and Nixon was so agitated and discomposed that they decided to handle the matter without him:

- "When Kissinger asked Haig whether should be wakened, the White House chief of staff replied firmly 'No.' Haig clearly shared Kissinger's feelings that Nixon was in no shape to make weighty decisions" (Rabinovich, 480).

The meeting produced a conciliatory response, which was sent (in Nixon's name) to Brezhnev. At the same time, it was decided to increase the Defense Condition (DEFCON) from four to three, the highest peacetime level. Lastly, they approved a message to Sadat (again, in Nixon's name) asking him to drop his request for Soviet assistance, and threatening that if the Soviets were to intervene, so would the United States (Rabinovich, 480).

The Soviets quickly detected the increased American defense condition, and were astonished and bewildered at the response. "Who could have imagined the Americans would be so easily frightened," said Nikolai Podgorny. "It is not reasonable to become engaged in a war with the United States because of Egypt and Syria," said Premier Alexei Kosygin, while KGB chief Yuri Andropov added that "We shall not unleash the Third World War" (Rabinovich, 484). In the end, the Soviets reconciled themselves to an Arab defeat. The letter from the American cabinet arrived during the meeting. Brezhnev decided that the Americans were too nervous, and that the best course of action would be to wait to reply (Rabinovich, 485). The next morning, the Egyptians agreed to the American suggestion, and dropped their request for assistance from the Soviets, bringing the crisis to an end.

Northern front de-escalation

On the northern front, the Syrians had been preparing for a massive counter-attack, scheduled for October 23. In addition to Syria's five divisions, Iraq had supplied two, and there were smaller complements of troops from other Arab countries, including Jordan. The Soviets had replaced most of the losses Syria's tank forces had suffered during the first weeks of the war.

However, the day before the offensive was to begin, the United Nations imposed its cease-fire (following the acquiescence of both Israel and Egypt). "The acceptance by Egypt of the cease-fire on Monday created a major dilemma for Assad. The cease-fire did not bind him, but its implications could not be ignored. Some on the Syrian General Staff favored going ahead with the attack, arguing that if it did so Egypt would feel obliged to continue fighting as well… Others, however, argued that continuation of the war would legitimize Israel's efforts to destroy the Egyptian Third Army. In that case, Egypt would not come to Syria's assistance when Israel turned its full might northward, destroying Syria's infrastructure and perhaps attacking Damascus" (Rabinovich, 464-465)

Ultimately, Assad decided to call off the offensive, and on October 23, Syria announced it had accepted the cease-fire, and the Iraqi government ordered its forces home.

Post-cease-fire negotiations

Organized fighting on all fronts ended by October 26. The cease-fire did not end the sporadic clashes along the cease-fire lines, nor did it dissipate military tensions. With the third Army cut off and without any means of resupply, it was effectively a hostage to the Israelis.

Israel received Kissinger's threat to support a UN withdrawal resolution, but before they could respond, Egyptian national security advisor Hafez Ismail sent Kissinger a stunning message—Egypt was willing to enter into direct talks with the Israelis, provided that the Israelis agree to allow nonmilitary supplies to reach their army and agree to a complete cease-fire.

The talks took place on October 28, between Israeli Major General Aharon Yariv and Egyptian Major General Muhammad al-Ghani al-Gamasy. Ultimately, Kissinger brought the proposal to Sadat, who agreed almost without debate. United Nations checkpoints were brought in to replace Israeli checkpoints, nonmilitary supplies were allowed to pass, and prisoners-of-war were to be exchanged. A summit in Geneva followed, and ultimately, an armistice agreement was worked out. On January 18, Israel signed a pullback agreement to the west side of the canal, and the last of their troops withdrew on March 5, 1974 (Rabinovich, 493).

Shuttle diplomacy by Henry Kissinger eventually produced a disengagement agreement on May 31, 1974, based on exchange of prisoners-of-war, Israeli withdrawal to the Purple Line and the establishment of a UN buffer zone. The UN Disengagement and Observer Force (UNDOF) was established as a peacekeeping force in the Golan.

Long-term effects of the war

The peace discussion at the end of the war was the first time that Arab and Israeli officials met for direct public discussions since the aftermath of the 1948 war.

For the Arab nations (and Egypt in particular), the psychological trauma of their defeat in the Six-Day War had been healed. In many ways, it allowed them to negotiate with the Israelis as equals. However, given that the war had started about as well as the Arab leaders could have wanted, at the end they had made only limited territorial gains in the Sinai front, while Israel gained more territory on the Golan Heights than it held before the war; also given the fact that Israel managed to gain a foothold on African soil west of the canal, the war helped convince many in the Arab world that Israel could not be defeated militarily, thereby strengthening peace movements.

The war had a stunning effect on the population in Israel. Following their victory in the Six-Day War, the Israeli military had become complacent. The shock and sudden defeats that occurred at the beginning of the war sent a terrible psychological blow to the Israelis, who had thought they had military supremacy in the region. (Rabinovich, 497–498) However, in time, they began to realize that "Reeling from a surprise attack on two fronts with the bulk of its army still unmobilized, and confronted by staggering new battlefield realities, Israel's situation was one that could readily bring strong nations to their knees. Yet, within days, it had regained its footing and within less than two weeks it was threatening both enemy capitals", "an achievement having few historical parallels." (Rabinovich, 498). However, in Israel, the casualty rate was high. Proportionately, Israel suffered as many casualties in 3 weeks of fighting as the United States did during almost a decade of fighting in Vietnam.

In response to U.S. support of Israel, OAPEC nations, the Arab members of OPEC, led by Saudi Arabia, decided to reduce oil production by 5% per month on October 17, and threatened an embargo. President Nixon then appealed to Congress on October 18th for $2.2 billion for arms shipments to Israel. On October 20th, in the midst of the war, Saudi Arabia declared an embargo against the United States, later joined by other oil exporters and extended against the Netherlands and other states, causing the 1973 energy crisis. Though widely believed to be a reaction to the war, it now appears that the embargo had been coordinated in a secret visit of Anwar Sadat to Saudi Arabia in August.

Any hope among the Egyptian government that this war would distract the Egyptian population from internal grievances, were nullified by a massively destructive anti-government food riot in Cairo with the slogan "Hero of the crossing, where is our breakfast?" ("يا بطل ﺍﻟﻌﺒﻮﺭ، فين الفطور؟", "Yā batl al-`abūr, fēn al-futūr?").

Fallout in Israel

A protest against the Israeli government started four months after the war ended. It was led by Moti Ashkenazi, commander of Budapest, the northernmost of the Bar-Lev forts and the only one during the war not to be captured by the Egyptians (Rabinovich, 499). Anger against the Israeli government (and Dayan in particular) was high. Shimon Agranat, President of the Israeli Supreme Court, was asked to lead an inquiry, the Agranat Commission, into the events leading up to the war and the setbacks of the first few days (Rabinovich, 501).

The Agranat Commission published its preliminary findings on April 2, 1974. Six people were held particularly responsible for Israel's failings:

- IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar was recommended for dismissal, after the Commission found he bore "personal responsibility for the assessment of the situation and the preparedness of the IDF."

- Chief of Intelligence Eli Zeira and his deputy, Aryeh Shalev, were recommended for dismissal.

- Lt. Colonel Bandman, head of the Aman desk for Egypt, and Lt. Colonel Gedelia, chief of intelligence for the Southern Command, were recommended for transfer away from intelligence duties.

- Shmuel Gonen, commander of the Southern front, was recommended by the initial report to be relieved of active duty (Rabinovich, 502). He was forced to leave the army after the publication of the Commission's final report, on January 30, 1975, which found that "he failed to fulfill his duties adequately, and bears much of the responsibility for the dangerous situation in which our troops were caught."

Rather than quieting public discontent, the report—which "had stressed that it was judging the ministers' responsibility for security failings, not their parliamentary responsibility, which fell outside its mandate"—inflamed it. Although it had cleared Meir and Dayan of all responsibility, public calls for their resignation (especially Dayan's) became more vociferous (Rabinovich, 502).

Finally, on April 11, 1974, Golda Meir resigned. Her cabinet followed suit, including Dayan, who had previously offered to resign twice and was turned down both times by Meir. Yitzhak Rabin, who had spent most of the war as an advisor to Elazar in an unofficial capacity (Rabinovich, 237), became head of the new Government, which was seated in June.

Camp David Accords

Main article: Camp David Accords (1978)Rabin's government was hamstrung by a pair of scandals, and he was forced to step down in 1977. The right-wing Likud party, under the prime ministership of Menachem Begin, won the elections that followed. This marked a historic change in the Israeli political landscape as for the first time since Israel's founding, a coalition not led by the Labour party was in control of the government.

Sadat, who had entered the war in order to recover the Sinai, grew frustrated at the slow pace of the peace process. In November 1977, he took the unprecedented step of visiting Israel, becoming the first Arab leader to do so (and implicitly recognizing Israel's right to exist).

The act jump-started the peace process. United States President Jimmy Carter invited both Sadat and Begin to a summit at Camp David to negotiate a final peace. The talks took place from September 5–17, 1978. Ultimately, the talks succeeded, and Israel and Egypt signed the Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty in 1979. Israel withdrew its troops and settlers from the Sinai, in exchange for normal relations with Egypt and a lasting peace.

Many in the Arab community were outraged at Egypt's peace with Israel. Egypt was expelled from the Arab League. Until then, Egypt had been "at the helm of the Arab world" (Karsh, 86).

Anwar Sadat was assassinated two years later, on October 6, 1981, while attending a parade marking the eighth anniversary of the start of the war, by Army members who were outraged at his negotiations with Israel.

Commemorations

October 6 is a national holiday in Egypt called Armed Forces Day.

In commemoration of the war, many places in Egypt were named after the October 6 date and Ramadan 10, its equivalent in the Islamic calendar (6th of October city and 10th of Ramadan city).

Notes

- ^ Yom Kippur War at sem40.com (in Russian)

- During the Fall of 2003, following the declassification of key Aman documents, Yedioth Ahronoth released a series of controversial articles which revealed that key Israeli figures were aware of considerable danger that an attack was likely, including Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan, but decided not to act. The two journalists leading the investigation, Ronen Bergman and Gil Meltzer, later went on to publish Yom Kippur War, Real Time: The Updated Edition, Yediot Ahronoth/Hemed Books, 2004. ISBN 9655115976

- "The Jarring initiative and the response," Israel's Foreign Relations, Selected Documents, vols. 1–2, 1947–1974 (accessed June 9, 2005).

- Doron Geller, "Israeli Intelligence and the Yom Kippur War of 1973," "JUICE", The Department for Jewish Zionist Education, The Jewish Agency for Israel (accessed November 27th, 2005).

- ^ "Shattered Heights: Part 1," Jerusalem Post, September 25, 1998 (accessed June 9, 2005).

- Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, Louis Perez, pg 377–379

- The Yom Kippur War at Zionism and Israel Information Center (accessed November 27th, 2005).

- Findings of the Agranat Commission, The Jewish Agency for Israel, see "January 30" on linked page (accessed June 9, 2005).

References

- In Search of Identity: An Autobiography by Anwar Sadat.

- Man of Defiance: A Political Biography of Anwar Sadat by Raphael Israeli.

- Syria and Israel: From War to Peacemaking by Moshe Maòz.

- The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East by Abraham Rabinovich. ISBN 0805241760

- The Iran-Iraq War, 1980–1988 by Efraim Karsh. ISBN 1841763713

- Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs — The Jarring initiative and the response

- Jewish Education Dept., JAFI, Israeli Intelligence and the Yom Kippur War of 1973

- Jerusalem Post's — Yom Kippur War: Shattered Heights

- Jewish Agency for Israel's Timeline of Israeli history

- Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work by Robert A. Pape

- The Road to Ramadan by Mohamed Heikal.

- Inside the Kremlin During the Yom Kippur War by Victor Israelyan, 1995 ISBN 0-271-01489-X, ISBN 0-271-01737-6

- Put an end to Israeli aggression, an article printed in the Pravda newspaper on October 12, 1973 (translation at CNN)

External links

- Maps: Egypt

- Maps: Syria

- The October War and US Policy — Provided by the National Security Archive.

- A Cry From The Bunkers — Dramatic and authentic recordings by IDF soldier Avi Yaffe from inside the IDF position, under attack at the outbreak of the war.

Categories: