This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 204.86.64.67 (talk) at 18:07, 16 February 2012. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:07, 16 February 2012 by 204.86.64.67 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) | |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

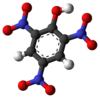

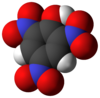

| IUPAC name 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol | |||

| Other names Carbazotic Acid; phenol trinitrate; picronitric acid; trinitrophenol; 2,4,6-trinitro-1-phenol; 2-hydroxy-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene; TNP; Melinite | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| CAS Number | |||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.696 | ||

| PubChem CID | |||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

| Chemical formula | C6H3N3O7 | ||

| Molar mass | 229.10 g·mol | ||

| Appearance | Colorless to yellow solid | ||

| Density | 1.763 g·cm, solid | ||

| Melting point | 122.5 °C | ||

| Boiling point | > 300 °C | ||

| Solubility in water | 14.0 g·L | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 0.38 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

| ||

| Explosive data | |||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |||

Picric acid is the chemical compound formally called 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP). This yellow crystalline solid is one of the most acidic phenols. Like other highly nitrated compounds such as TNT, picric acid is an explosive. Its name comes from Greek πικρος (pik' ros), meaning "bitter", reflecting its bitter taste.

History

Picric acid was probably first mentioned in the alchemical writings of Johann Rudolf Glauber in 1742. Initially, it was made by nitrating substances such as animal horn, silk, indigo, and natural resin, the synthesis from indigo first being performed by Peter Woulfe in 1779. Its synthesis from phenol, and the correct determination of its formula, were successfully accomplished in 1841. Not until 1830 did chemists think to use picric acid as an explosive. Before then, chemists assumed that only the salts of picric acid were explosive, not the acid itself. In 1873 Hermann Sprengel proved it could be detonated and most military powers used picric acid as their primary high explosive material. Picric acid is also used in the analytical chemistry of metals, ores, and minerals.

Picric acid was the first high explosive nitrated organic compound widely considered suitable to withstand the shock of firing in conventional artillery. Nitroglycerine and guncotton were available earlier but shock sensitivity sometimes caused detonation in the artillery barrel at the time of firing. In 1885, based on research of Hermann Sprengel, French chemist Eugène Turpin patented the use of pressed and cast picric acid in blasting charges and artillery shells. In 1887 the French government adopted a mixture of picric acid and guncotton under the name melinite. In 1888, Britain started manufacturing a very similar mixture in Lydd, Kent, under the name lyddite. Japan followed with an "improved" formula known as shimose powder. In 1889, a similar material, a mixture of ammonium cresylate with trinitrocresol, or an ammonium salt of trinitrocresol, started to be manufactured under the name ecrasite in Austria-Hungary. By 1894 Russia was manufacturing artillery shells filled with picric acid. Ammonium picrate (known as Dunnite or explosive D) was used by the United States beginning in 1906. However, shells filled with picric acid become highly unstable if the compound reacts with metal shell or fuze casings to form metal picrates which are more sensitive than the parent phenol. The sensitivity of picric acid was demonstrated in the Halifax Explosion. Picric acid was used in the Battle of Omdurman, Second Boer War, the Russo-Japanese War, and World War I. Germany began filling artillery shells with TNT in 1902. Toluene was less readily available than phenol, and TNT is less powerful than picric acid, but improved safety of munitions manufacturing and storage caused replacement of picric acid by TNT for most military purposes between the World Wars.

Synthesis

The aromatic ring of phenol is highly activated towards electrophilic substitution reactions, and attempted nitration of phenol, even with dilute nitric acid, results in the formation of high molecular weight tars. In order to minimize these side reactions, anhydrous phenol is sulfonated with fuming sulfuric acid, and the resulting p-phenolsulfonic acid is then nitrated with concentrated nitric acid. During this reaction, nitro groups are introduced, and the sulfonic acid group is displaced. The reaction is highly exothermic, and careful temperature control is required.

Uses

By far the largest use has been in munitions and explosives.

It has found some use in organic chemistry for the preparation of crystalline salts of organic bases (picrates) for the purpose of identification and characterization.

In metallurgy a picric acid etch has been commonly used in optical metallography to reveal prior austenite grain boundaries in ferritic steels. The hazards associated with picric acid has meant it has largely been replaced with other chemical etchants.

Bouin solution is a common picric acid-containing fixative solution used for histology specimens.

Workplace drug testing utilizes picric acid for the Jaffe Reaction to test for creatinine. It forms a colored complex that can be measured using spectroscopy.

Much less commonly, wet picric acid has been used as a skin dye or temporary branding agent. It reacts with proteins in the skin to give a dark brown color that may last as long as a month.

In the early 20th century, picric acid was stocked in pharmacies as an antiseptic and as a treatment for burns, malaria, herpes, and smallpox. It was most notably used for the treatment of burns suffered by victims of the Hindenburg disaster in 1937.

Picric acid emits a high-pitched whine during combustion in air and this has led to its widespread use in fireworks.

Picric acid has been used for many years by fly tyers to dye mole skins and feathers dark olive green. Its popularity has been tempered by its toxic nature.

Safety

Modern safety precautions recommend storing picric acid wet. Dry picric acid is relatively sensitive to shock and friction, so laboratories that use it store it in bottles under a layer of water, rendering it safe. Glass or plastic bottles are required, as picric acid can easily form metal picrate salts that are even more sensitive and hazardous than the acid itself. Industrially, picric acid is especially hazardous because it is volatile and slowly sublimes even at room temperature. Over time, the buildup of picrates on exposed metal surfaces can constitute a grave hazard.

Bomb disposal units are often called to dispose of picric acid if it has dried out.

References

- ^ Brown, G.I. (1998) The Big Bang: a History of Explosives Sutton Publishing ISBN 0-7509-1878-0 pp.151-163

- John Philip Wisser (1901). The second Boer War, 1899-1900. Hudson-Kimberly. p. 243. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- Dunnite Smashes Strongest Armor, The New York Times, August 18, 1907

- Marc Ferro. The Great War. London and New York: Routeladge Classics, p. 98.

- Carson, Freida L.; Hladik, Christa (2009). Histotechnology: A Self-Instructional Text (3 ed.). Hong Kong: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780891895817.

- Creatinine Direct Procedure, on CimaScientific

- JT Baker MSDS

- "Bomb squad called to Dublin lab". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 1 October 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Unstable chemicals made safe by army". rte.ie. RTÉ New. 3 November 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Army bomb disposal team make Kerry scene safe". irishexaminer.com. Irish Examiner. 22 November 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Dangerous chemicals made safe". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Unstable chemicals made safe". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Chemicals Blown Up At Transfer Station". kcra.com. KCRA. 6 January 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- Cooper, Paul W., Explosives Engineering, New York: Wiley-VCH, 1996. ISBN 0-471-18636-8

- Safety Information