This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Franamax (talk | contribs) at 17:05, 19 October 2012 (Undid revision 518727299 by DogBoy38930 (talk) rv unexplained removal). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:05, 19 October 2012 by Franamax (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 518727299 by DogBoy38930 (talk) rv unexplained removal)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) City in Mississippi, United States| Greenwood, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| Nickname: Cotton Capital of the World | |

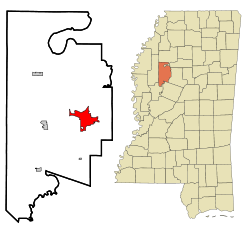

Location of Greenwood, Mississippi Location of Greenwood, Mississippi | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Leflore |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13 sq mi (33.7 km) |

| • Land | 12.4 sq mi (32.1 km) |

| • Water | 0.6 sq mi (1.6 km) |

| Elevation | 131 ft (40 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 18,425 |

| • Density | 1,997.8/sq mi (771.6/km) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 38930, 38935 |

| Area code | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-29340 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0670714 |

| Website | www |

Greenwood is a city in and the county seat of Leflore County, Mississippi,Template:GR located at the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta approximately 96 miles north of Jackson, Mississippi, and 130 miles south of Memphis, Tennessee. The population was 15,205 at the 2010 census. It is the principal city of the Greenwood Micropolitan Statistical Area. The Tallahatchie River and the Yalobusha River meet at Greenwood to form the Yazoo River.

History

The flood plain of the Mississippi River has long been an area rich in vegetation and wildlife, feeding off the Mississippi and its numerous tributaries. Long before Europeans migrated to America, the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian nations settled in the Delta's bottomlands and throughout what is now central Mississippi. They were descended from indigenous peoples who had lived in the area for thousands of years.

In the nineteenth century, the Five Civilized Tribes suffered increasing encroachment on their territory by European-American settlers from southeastern states. Under pressure from the United States government, in 1830 the Choctaw principal chief Greenwood Leflore and other Choctaw leaders signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, ceding most of their remaining land to the United States in exchange for land in what is now southeastern Oklahoma. The government opened the land to settlement by European Americans.

The first Euro-American settlement on the banks of the Yazoo River was a trading post founded by John Williams in 1830 and known as Williams Landing. The settlement quickly blossomed, and in 1844 was incorporated as "Greenwood," named after Chief Greenwood Leflore. Growing in the midst of a strong cotton market, the city's success was based on its strategic location in the heart of the Delta; on the easternmost point of the alluvial plain and astride the Tallahatchie and the Yazoo rivers. The city served as a shipping point for cotton to major markets in New Orleans, Louisiana, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Memphis, Tennessee, and St. Louis, Missouri. Greenwood continued to prosper, based on slave labor on the cotton plantations and in shipping, until the latter part of the American Civil War.

The end of the Civil War in 1865 and the following years of Reconstruction changed the labor market to one of free labor. The state was mostly undeveloped frontier, and many freedmen withdrew from working for others. In the nineteenth century, many blacks managed to clear and buy their own farms in the bottomlands. With the disruption of war and changes to labor, cotton production initially declined, reducing the city's previously thriving economy.

The construction of railroads through the area in the 1880s allowed the city to revitalize, with two rail lines running to downtown Greenwood, close to the Yazoo River, and shortening transportation to markets. Greenwood again emerged as a prime shipping point for cotton. Downtown's Front Street bordering the Yazoo filled with cotton factors and related businesses, earning that section the name Cotton Row. The city continued to prosper in this way well into the 1940s, although cotton production suffered during the infestation of the boll weevil in the early 20th century. For many years, the bridge over the Yazoo displayed the sign, "World's Largest Inland Long Staple Cotton Market".

The industry was largely mechanized in the 20th century before World War II. Since the late 20th century, some Mississippi farmers have begun to replace cotton with corn and soybeans as commodity crops, because of the shift of the textile industry overseas, and stronger prices for those crops.

Greenwood's Grand Boulevard was once named one of America's 10 most beautiful streets by the U.S. Chambers of Commerce and the Garden Clubs of America. Sally Humphreys Gwin, a charter member of the Greenwood Garden Club, planted the 1,000 oak trees lining Grand Boulevard. In 1950, Gwin received a citation from the National Congress of the Daughters of the American Revolution in recognition of her work in the conservation of trees.

The civil rights era in Greenwood

In 1955, following the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the White Citizens' Council was founded by Robert B. Patterson in Greenwood to fight against racial integration. Local chapters formed across the state, and the white-dominated legislature voted to give the Councils financial support. Having been disfranchised since 1890, when the state passed a new constitution and related electoral and Jim Crow laws, the black community had not been able to elect representatives since then to the state or federal legislature, and could not protest such actions. The Council paid staff to collect information on black professionals and activists who worked for the restoration of American constitutional civil rights.

From 1962 until 1964, Greenwood was a center of protests and voter registration struggles during the Civil Rights Movement. The SNCC, COFO, and the MFDP were all active in Greenwood. During this period, hundreds were arrested in nonviolent protests; civil rights activists were subjected to repeated violence, and whites used economic retaliation against African Americans who attempted to register to vote. The city police set their police dog, Tiger, on protesters while white counter-protesters yelled "Sic 'em" from the sidewalk. When Martin Luther King visited the city later in 1963, the Ku Klux Klan distributed a flyer which read in part (capitalization in original):

TO THOSE OF YOU NIGGERS WHO GAVE OR GIVE AID AND COMFORT TO THIS CIVIL RIGHTS SCUM, WE ADVISE YOU THAT YOUR IDENTITIES ARE IN THE PROPER HANDS AND YOU WILL BE REMEMBERED. WE KNOW THAT THE NIGGER OWNER OF COLLINS SHOE SHOP ON JOHNSON STREET "ENTERTAINED" MARTIN LUTHER KING WHEN THE "BIG NIGGER" CAME TO GREENWOOD. WE KNOW OF OTHERS AND WE SAY TO YOU — AFTER THE SHOWING AND THE PLATE-PASSING AND STUPID STREET DEMONSTRATIONS ARE OVER AND THE IMPORTED AGITATORS HAVE ALL GONE, ONE THING IS SURE AND CERTAIN — YOU ARE STILL GOING TO BE NIGGERS AND WE ARE STILL GOING TO BE WHITE MEN. YOU HAVE CHOSEN YOUR BEDS AND NOW YOU MUST LIE IN THEM.

In the mid 1960s, the Congress passed the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act to enforce constitutional rights of African Americans and other minorities. For some time, voter registration and elections were monitored by the federal government because of historic discrimination against blacks in the state. The proportion of black citizens of Mississippi who were registered to vote finally roughly matched their proportion of the population in the late 1980s.

On December 3, 2010, Frederick Jermaine Carter, an African-American man from Sunflower County with a history of mental illness, was found dead, hanging from a tree in north Greenwood. The Leflore county coroner ruled the death a suicide, but the NAACP and Mississippi state senator David Jordan are concerned that foul play may have been involved. Jordan explicitly tied the black community's suspicions about the verdict to the state's history of racial violence against blacks. The reporter Larry Copeland for USA Today, noted that the young Emmett Till had been lynched 12 miles away in 1955. Jordan said, "We're not drawing any conclusions. We're skeptical, and rightfully we should be, given our history. We can't take this lightly. We just have to wait and see."

Geography

Greenwood is located at 33°31′7″N 90°11′2″W / 33.51861°N 90.18389°W / 33.51861; -90.18389 (33.518719, -90.183883)Template:GR. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.5 square miles (25 km), of which 9.2 square miles (24 km) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.78 km) is water.

As of 1998, the northern portion of Greenwood is almost all White and the southern half is mostly black. Greenwood is 30 miles (48 km) from the nearest interstate highway. It is 90 miles (140 km) north of Jackson.

Demographics

At the 2000 censusTemplate:GR, there were 18,425 people, 6,916 households and 4,523 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,997.8 per square mile (771.6/km²). There are 7,565 housing units at an average density of 820.3 per square mile (316.8/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 32.82% White, 65.36% Black, 0.11% Native American, 0.91% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 0.24% from other races, and 0.48% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.03% of the population.

There were 6,916 households of which 34.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.4% are married couples living together, 27.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.6% were non-families. 31.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.29.

31.0% of the population were under the age of 18, 10.3% from 18 to 24, 26.7% from 25 to 44, 18.6% from 45 to 64, and 13.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females there were 84.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.9 males.

The median household income was $21,867 and the median family income was $26,393. Males had a median income of $27,267 versus $18,578 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,461. 33.9% of the population and 28.8% of families are below the poverty line. Of the total population, 47.0% of those under the age of 18 and 20.0% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

Mississippi Blues Trail markers

Radio station WGRM on Howard Street was the location of B.B. King's first live broadcast in 1940. On Sunday nights, King performed live gospel music as part of a quartet. In memory of this event, the Mississippi Blues Trail has placed its third historic marker in this town at the site of the former radio station. Another Mississippi Blues trail marker is placed near the grave of the blues singer Robert Johnson. There is also a Blues Trail marker at the Elks Lodge.

Government and infrastructure

Local government

Greenwood is governed under the city council form of government composed of council members from seven wards and headed by a mayor.

State and federal representation

The Delta Correctional Facility, operated by the Corrections Corporation of America on behalf of the Mississippi Department of Corrections, is located in Greenwood. It is a medium-security prison, owned by the state of Mississippi, and privately operated. As of 1998 the largest employer to have moved into the area in that period of time was the prison. In 1998 it had 1,000 prisoners. About 950 of them were black.

The United States Postal Service operates two post offices in Greenwood. They are the Greenwood Post Office and the Leflore Post Office.

Media and publishing

Newspapers, magazines and journals

- The Greenwood Commonwealth (published daily except Saturday)

- Leflore Illustrated (quarterly)

Television

AM/FM radio

- WABG, 960 AM (blues)

- WGNG, 106.3 FM (hip-hop/urban contemporary)

- WGNL, 104.3 FM (urban adult contemporary/blues)

- WGRM, 1240 AM (gospel)

- WGRM-FM, 93.9 FM (gospel)

- WKXG, 1540 AM (silent pending transfer)

- WMAO-FM, 90.9 FM (NPR broadcasting)

- WYMX, 99.1 FM (oldies)

Transportation

Railroads

Greenwood is served by two major rail lines. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Greenwood, connecting New Orleans to Chicago from Greenwood station.

Air transportation

Greenwood is served by Greenwood-Leflore Airport (GWO) to the east and is located midway between Jackson, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee, and about halfway between Dallas, Texas, and Atlanta, Georgia.

Highways

- U.S. Route 82 runs through Greenwood on its way from the White Sands of New Mexico (east of Las Cruces) east to Georgia's Atlantic coast (Brunswick, Georgia).

- U.S. Route 49 passes through Greenwood as it stretches between Piggott, Arkansas, south to Gulfport.

- Other Greenwood highways include Mississippi Highway 7.

Education

Greenwood Public School District operates public schools. Greenwood High School is the only public high school in Greenwood. Around 1988 it was split almost evenly between black and white students. In 1998, it was 92% black.

Leflore County School District operates schools outside the Greenwood city area, including Amanda Elzy High School.

Pillow Academy, a private school, is located in unincorporated Leflore County, near Greenwood. It was originally a segregation academy.

Notable natives and residents

- Valerie Brisco-Hooks, Olympic athlete

- Fred Carl, Jr., founder/CEO of Viking Range Corp.

- William V. Chambers, personality psychologist

- Byron De La Beckwith, white supremacist, assassinated Civil Rights leader Medgar Evers

- Carlos Emmons, professional football player

- Betty Everett, R&B vocalist and pianist

- Alphonso Ford, professional basketball player

- Webb Franklin, United States Congressman

- Morgan Freeman, Oscar-winning actor

- Jim Gallagher, Jr., professional golfer

- Bobbie Gentry, singer/songwriter

- Gerald Glass, professional basketball player

- Guitar Slim, blues musician

- Lusia Harris, basketball player

- Kent Hull, professional football player

- Tom Hunley, ex-slave and the real-life Hambone in J. P. Alley's syndicated cartoon feature, Hambone's Meditations

- Jermaine Jones, soccer player for Blackburn Rovers and United States national team

- Greenwood LeFlore, American Indian leader (Choctaw chief)

- Cleo Lemon, Toronto Argonauts quarterback

- Walter "Furry" Lewis, blues musician

- Bernie Machen, president of University of Florida

- Paul Maholm, baseball pitcher

- Matt Miller, baseball pitcher

- Mulgrew Miller, jazz pianist

- Carrie Nye, actress

- Fenton Robinson, blues singer/guitarist

- Richard Rubin, writer and journalist

- Donna Tartt, novelist

- Tonea Stewart, actress

- Hubert Sumlin, blues guitarist

- Willye B. White, Olympic athlete

- Booker Wright, restaurant owner (Booker's Place)

References

- John C. Willis, Forgotten Time: The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta after the Civil War. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000

- Krauss, Clifford. "Mississippi Farmers Trade Cotton Plantings for Corn", The New York Times, May 5, 2009

- Delta Democrat-Times, November 26, 1956.

- Kirkpatrick, Mario Carter. Mississippi Off the Beaten Path. GPP Travel, 2007

- "White Citizens' Councils aimed to maintain 'Southern way of life'". Jackson Sun.

- Stephen Edward Cresswell, Rednecks, Redeemers and Race: Mississippi after Reconstruction, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006, p. 124

- Mississippi Voter Registration — Greenwood ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul (2003). Sons of Mississippi. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40461-9.

- Chandler Davidson; Bernard Grofman (27 May 1994). Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, 1965-1990. Princeton University Press. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-691-02108-9. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Larry Copeland (6 December 2010). "NAACP contests suicide as cause of hanged man's death". USA Today. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Rubin, Richard. "Should the Mississippi Files Have Been Re-opened? No, because." The New York Times. August 30, 1998. Retrieved on March 25, 2012.

- Dufresne, Marcel. "Exposing the Secrets of Mississippi Racism." American Journalism Review. October 1991. Retrieved on March 25, 2012.

- Cloues, Kacey. "Great Southern Getaways - Mississippi" (PDF). www.atlantamagazine.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- "Historical marker placed on Mississippi Blues Trail". Associated Press. January 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

- "Film crew chronicles blues markers" (PDF). The Greenwood Commonwealth. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- Widen, Larry. "JS Online: Blues trail". www.jsonline.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- "Mississippi Blues Commission - Blues Trail". www.msbluestrail.org. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- "Private Prisons." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- "Ward Map." City of Greenwood. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- "Post Office Location - GREENWOOD." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- "Post Office Location - LEFLORE." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- Lynch, Adam (18 November 2009). "Ceara's Season". Jackson Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

External links

| Municipalities and communities of Leflore County, Mississippi, United States | ||

|---|---|---|

| County seat: Greenwood | ||

| Cities |  | |

| Towns | ||

| CDP | ||

| Unincorporated communities | ||

| Ghost town | ||

| Footnotes | ‡This populated place also has portions in an adjacent county or counties | |