This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Lawstubes (talk | contribs) at 18:37, 17 January 2013 (no methyl, amphetamine is 1-phenylpropan-2-amine. methamphetamine is n-methyl-1-phenyl-propan-2-amine.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:37, 17 January 2013 by Lawstubes (talk | contribs) (no methyl, amphetamine is 1-phenylpropan-2-amine. methamphetamine is n-methyl-1-phenyl-propan-2-amine.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Amphetamine (disambiguation).Pharmaceutical compound

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | alpha-methylbenzeneethanamine, alpha-methylphenethylamine, beta-phenyl-isopropylamine |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous, vaporization, insufflation, rectal, sublingual |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | nasal 75%; rectal 95–99%; intravenous 100% |

| Protein binding | 15–40% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2D6) |

| Elimination half-life | 12h average for d-isomer, 13h for l-isomer |

| Excretion | Renal; significant portion unaltered |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.543 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H13N |

| Molar mass | 135.2084 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Solubility in water | 50–100 mg/mL (16C°) mg/mL (20 °C) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Amphetamine (USAN, abbreviated from alpha-phenethylamine), α-methylphenethylamine, or amfetamine (INN) is a psychostimulant drug of the phenethylamine class that produces increased wakefulness and focus in association with decreased fatigue and appetite.

Brand names of medications that contain, or metabolize into, amphetamine, include Adderall, Dexedrine, Dextroamphet, Dextrostat, Didrex, ProCentra, and Vyvanse, as well as Benzedrine or Psychedrine in the past.

The drug is also used recreationally and as a performance enhancer.

Important side effects of therapeutic amphetamine include stunted growth in young people and occasionally a psychosis can occur at therapeutic doses during chronic therapy as a treatment emergent side effect. When used at high doses the risk of experiencing side effects and their severity increases.

Effects

Physical effects

Physical effects of amphetamine can include hyperactivity, dilated pupils, vasoconstriction, blood shot eyes, flushing, restlessness, dry mouth, bruxism, headache, tachycardia, bradycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, hypotension, fever, diaphoresis, diarrhea, constipation, blurred vision, aphasia, dizziness, twitching, insomnia, numbness, palpitations, arrhythmias, tremors, dry and/or itchy skin, acne, pallor, convulsions, and with chronic and/or high doses, seizure, stroke, coma, heart attack and death can occur.

Psychological effects

Psychological effects can include euphoria, anxiety, increased libido, alertness, concentration, energy, self-esteem, self-confidence, sociability, irritability, aggression, psychosomatic disorders, psychomotor agitation, grandiosity, repetitive and obsessive behaviors, paranoia, and with chronic and/or high doses, amphetamine psychosis can occur. Occasionally this psychosis can occur at therapeutic doses during chronic therapy as a treatment emergent side effect.

Withdrawal effects

Withdrawal symptoms of amphetamine consist primarily of mental fatigue, mental depression and increased appetite. Symptoms may last for days with occasional use and weeks or months with chronic use, with severity dependent on the length of time and the amount of amphetamine used. Withdrawal symptoms may also include anxiety, agitation, excessive sleep, vivid or lucid dreams, deep REM sleep and suicidal ideation.

Side effects

Side effects may consist of severe weight loss, also dependence may develop during use of this drug. Smoking this specific drug may induce a higher threat of dependence for first time users. Amphetamine can also raise the heart rate to dangerous levels.

Contraindications

Amphetamine elevates cardiac output and blood pressure making it dangerous for use by patients with a history of heart disease or hypertension. Amphetamine can cause life-threatening complications in patients taking MAOI antidepressants. The use of amphetamine and amphetamine-like drugs is contraindicated in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma or anatomically narrow angles. Like other sympathomimetic amines, amphetamine can induce transient mydriasis. In patients with narrow angles, pupillary dilation can provoke an attack of angle-closure glaucoma. These agents should also be avoided in patients with other forms of glaucoma, as mydriasis may occasionally increase interocular pressure.

Amphetamine has been shown to pass through into breast milk. Because of this, mothers taking amphetamine are advised to avoid breastfeeding during their course of treatment.

Dependence and addiction

Main article: Amphetamine dependenceTolerance is developed rapidly in amphetamine abuse; therefore, periods of extended use require increasing amounts of the drug in order to achieve the same effect.

Overdose

An amphetamine overdose is rarely fatal but can lead to a number of different symptoms, including psychosis, chest pain, and hypertension.

Psychosis

Main article: Stimulant psychosisAbuse of amphetamines can result in a stimulant psychosis that can present as a number of psychotic disorders (e.g. paranoia, hallucinations, delusions). In an Australian study of 309 active amphetamine users, 18% had experienced a clinical level psychosis in the past year. A Japanese study reported a 64% recovery rate within 10 days rising to a 82% recovery rate at 30 days after amphetamine cessation. However it has been suggested that about 5-15% of users fail to make a complete recovery from the psychosis in the long term.

Mechanism of action

Primary sites of action

Amphetamine exerts its behavioral effects by modulating several key neurotransmitters in the brain, including dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. However, the activity of amphetamine throughout the brain appears to be site-specific; certain receptors that respond to amphetamine in some regions of the brain tend not to do so in other regions. For instance, dopamine D2 receptors in the hippocampus, a region of the brain associated with forming new memories, appear to be unaffected by the presence of amphetamine.

The major neural systems affected by amphetamine are largely implicated in the brain’s reward circuitry. Moreover, neurotransmitters involved in various reward pathways of the brain appear to be the primary targets of amphetamine. One such neurotransmitter is dopamine, a chemical messenger heavily active in the mesolimbic and mesocortical reward pathways. Therefore, the anatomical components of these pathways — including the striatum, the nucleus accumbens, and the ventral striatum — have been found to be primary sites of amphetamine action.

The fact that amphetamine influences neurotransmitter activity specifically in regions implicated in reward provides insight into the behavioral consequences of the drug, such as the stereotyped onset of euphoria. A better understanding of the specific mechanisms by which amphetamine operates may increase our ability to treat amphetamine addiction and possibly other addictions (because the brain’s reward circuitry has been widely implicated in addictions of many types).

Related endogenous compounds

Amphetamine has been found to have several endogenous analogues; that is, molecules of a similar structure found naturally in the brain. examples include β-Phenethylamine and the amino acid l-Phenylalanine. These molecules are thought to modulate levels of excitement and alertness, among other related affective states.

Dopamine

The most widely studied neurotransmitter with regard to amphetamine action in the central nervous system is dopamine. All of the addictive drugs appear to enhance synaptic dopamine, including amphetamine and methamphetamine. Studies have shown that, in certain brain regions, amphetamine increases the concentrations of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, thereby heightening the response of the post-synaptic neuron.

The specific mechanisms by which amphetamine affects dopamine concentrations have been studied extensively. Currently, two major hypotheses have been proposed, which are not mutually exclusive. One theory emphasizes amphetamine’s actions on the vesicular level, increasing concentrations of dopamine in the cytosol of the pre-synaptic neuron. The other focuses on the role of the dopamine transporter DAT, and proposes that amphetamine may interact with DAT to induce reverse transport of dopamine from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft.

The former hypothesis is backed by studies from David Sulzer's lab at Columbia University demonstrating that injections of amphetamine result in rapid increases of cytosolic dopamine concentrations, while the drug decreases the number of dopamine molecules inside the synaptic vesicle. Amphetamine is a substrate for a specific neuronal synaptic vesicle uptake transporter called VMAT2. When amphetamine is taken up by VMAT2, the vesicle releases dopamine molecules into the cytosol in exchange. The redistributed dopamine is then believed to interact with DAT to promote reverse transport. Amphetamine and amphetamine derivatives are also weak bases that accept protons, and can collapse acidic pH gradients in the vesicles that would otherwise provide free energy for neurotransmitter accumulation: the "weak base hypothesis" of amphetamine action suggests that collapse of this free energy contributes to redistribution of dopamine from very high (molar) concentrations in the vesicles to the cytosol. Calcium may be a key molecule involved in the interactions between amphetamine and VMATs.

The increase of cytosolic dopamine appears to trigger neurotoxicity, as dopamine readily auto-oxidizes, so that amphetamine or methamphetamine's increase in cytosolic dopamine can lead to oxidative stress in the cytosol that in turn promotes autophagy-related degradation of dopamine axons and dendrites.

The second hypothesis of amphetamine action on the plasma membrane dopamine transporter postulates a direct interaction between amphetamine and the DAT. The activity of DAT is believed to depend on specific phosphorylating kinases, such as protein kinase c, to be specific PKC-β. Upon phosphorylation, DAT undergoes a conformational change that results in the transport of DAT-bound dopamine from the extracellular to the intracellular environment. In the presence of amphetamine, however, DAT has been observed to function in reverse, spitting dopamine out of the presynaptic neuron and into the synaptic cleft. Thus, beyond inhibiting reuptake of dopamine, amphetamine also stimulates the release of dopamine molecules into the synapse.

In support of the above hypothesis, it has been found that PKC-β inhibitors eliminate the effects of amphetamine on extracellular dopamine concentrations in the striatum of rats. This data suggests that the PKC-β kinase may represent a key point of interaction between amphetamine and the DAT transporter.

Additional actions of amphetamine contribute to its ability to release dopamine from neurons, including action as an inhibitor of monoamine oxidase, an enzyme responsible for dopamine breakdown in the cytosol; an ability to enhance dopamine synthesis it is presumed via actions on the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which synthesizes the dopamine precursor L-DOPA; and some blockade of the DAT, an action that amphetamine shares with cocaine. Due to the combination of these actions and its long half-life, amphetamine can release far more dopamine than can cocaine or other addictive drugs.

Serotonin

Amphetamine has been found to exert similar effects on serotonin as on dopamine. Like DAT, the serotonin transporter SERT can be induced to operate in reverse upon stimulation by amphetamine. This mechanism is thought to rely on the actions of calcium ions, as well as on the proximity of certain transporter proteins.

The interaction between amphetamine and serotonin is apparent only in particular regions of the brain, such as the mesocorticolimbic projection. Recent studies suggest that amphetamine may indirectly alter the behavior of glutamatergic pathways extending from the ventral tegmental area to the prefrontal cortex by increasing inhibitory serotonin receptor activity on glutamatergic neurons. Glutamatergic pathways are strongly correlated with increased excitability at the level of the synapse. Increased extracellular concentrations of serotonin may thus modulate the excitatory activity of glutamatergic neurons.

The proposed ability of amphetamine to decrease excitability of glutamatergic pathways may be of significance when considering the role of serotonin in addiction, evidence of which has been quickly accumulating. An additional behavioral consequence of postulated serotonergic effects of amphetamine may be alterations in the stereotyped locomotor stimulation that occurs in response to amphetamine exposure. Despite this, at least one study suggests that serotonergic effects are not necessary for the development of stereotypy in rodents treated with stimulants.

Other relevant neurotransmitters

Several other neurotransmitters have been linked to amphetamine activity. It is well-established that amphetamine causes increased brain and blood levels of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter related to adrenaline. This is believed to occur via reuptake blockage as well as via interactions with the norepinephrine neuronal transport carrier. Many in vitro studies have demonstrated that amphetamine binds to and inhibits reuptake of norepinephrine via norepinephrine transporter expressed on the cell membranes of primary neurons and cell-lines. In addition, amphetamine acts as a substrate for the transporter, being moved from the outside to the inside of the cell via the transporter. Once inside the cell, amphetamine can bind to VMAT2 on neurotransmitter-containing vesicles and via actions that are not well-understood, amphetamine increases release of norepinephrine.

In addition, extracellular levels of glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, have been shown to increase upon exposure to amphetamine. Consistent with other findings, this effect was found in the areas of the brain implicated in reward; namely, the nucleus accumbens, striatum, and prefrontal cortex.

The long-term effects of amphetamines use on neural development in children has not been well established. A study in rats suggests that high-dose amphetamine use during adolescence may impair adult working memory.

Pharmacology

Chemical properties

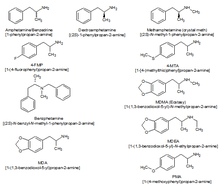

Amphetamine is a chiral compound. The racemic mixture can be divided into its optical isomers: levo- and dextro-amphetamine. Amphetamine is the parent compound of its own structural class, comprising a broad range of psychoactive derivatives, from empathogens, MDA (3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine) and MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) known as ecstasy, to the N-methylated form, methamphetamine known as 'meth', and to decongestants such as ephedrine (EPH) . Amphetamine is a homologue of phenethylamine.

At first, the medical drug came as the salt racemic-amphetamine sulfate (racemic-amphetamine contains both isomers in equal amounts). Attention disorders are often treated using Adderall or a generic equivalent, a formulation of mixed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine salts that contain

- 1/4 dextro-amphetamine saccharate

- 1/4 dextro-amphetamine sulfate

- 1/4 (racemic amphetamine) aspartate monohydrate

- 1/4 (racemic amphetamine) sulfate

In organic chemistry, amphetamine was found as excellent chiral ligand for stereoselective synthesis of 1,1'-Bi-2-naphthol.

Pharmacodynamics

Amphetamine has been shown to both diffuse through the cell membrane and travel via the dopamine transporter (DAT) to increase concentrations of dopamine in the neuronal terminal.

Amphetamine, both as d-amphetamine (dextroamphetamine) and l-amphetamine (or a racemic mixture of the two isomers), is believed to exert its effects by binding to the monoamine transporters and increasing extracellular levels of the biogenic amines dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and serotonin. It is hypothesized that d-amphetamine acts primarily on the dopaminergic systems, while l-amphetamine is norepinephrinergic (noradrenergic). The primary reinforcing and behavioral-stimulant effects of amphetamine, however, are linked to enhanced dopaminergic activity, primarily in the mesolimbic dopamine system.

Amphetamine and other amphetamine-type stimulants act principally to release dopamine into the synaptic cleft. Amphetamine, unlike dopamine transporter inhibitor cocaine, acts as a substrate for DAT and slows reuptake by a secondary acting mechanism through the phosphorylation of dopamine transporters.

A primary action of amphetamine is mediated by vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs); the transporters appear to provide a channel through which dopamine and other transmitters can exit the vesicle to the cytosol. According to the "weak base hypothesis" this is exacerbated by amphetamine acting to alkalinize the vesicle, which depletes the free energy favoring vesicle accummlation so that transmitter is redistributed to the cytosol. Together, these actions cause the release of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin from monoamine vesicles, thereby increasing cytosolic concentrations of transmitter. This increase in concentration assists in the "reverse transport" of dopamine via the dopamine transporter (DAT) into the synapse. In addition, amphetamine binds reversibly to the DATs and blocks the transporter's ability to clear DA from the synaptic space. Amphetamine also acts in this way with norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and to a lesser extent serotonin.

Amphetamine has been identified as a potent agonist of TAAR1, a newly discovered GPCR important for regulation of monoaminergic systems in the brain. Activation of TAAR1 increases cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase activation and inhibits transporter function. These effects increase monoamine efflux and prolong the amount of time monoamines remain in the synapse.

Pharmacokinetics

The half-life of racemic amphetamine is 12–13 hours and is excreted renally, with a significant portion unaltered. Metabolism takes place mostly in liver. Deamination into phenylacetone happens via CYP2C and renders the compounds inert. Phenylacetone is then further metabolized into benzoic acid and hippuric acid.

History

Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 by the Romanian chemist Lazăr Edeleanu in Berlin, Germany. He named the compound phenylisopropylamine. It was one of a series of compounds related to the plant derivative ephedrine, which had been isolated from the plant Ma-Huang (Ephedra) that same year by Nagayoshi Nagai. No pharmacological use was found for amphetamine until 1927, when pioneer psychopharmacologist Gordon Alles resynthesized and tested it on himself, in search of an artificial replacement for ephedrine. From 1933 or 1934 Smith, Kline and French began selling the volatile base form of the drug as an inhaler under the trade name Benzedrine, useful as a decongestant but readily usable for other purposes. One of the first attempts at using amphetamine as a scientific study was done by M. H. Nathanson, a Los Angeles physician, in 1935. He studied the subjective effects of amphetamine in 55 hospital workers who were each given 20 mg of Benzedrine. The two most commonly reported drug effects were "a sense of well being and a feeling of exhilaration" and "lessened fatigue in reaction to work". During World War II amphetamine was extensively used to combat fatigue and increase alertness in soldiers. After decades of reported abuse, the FDA banned Benzedrine inhalers, and limited amphetamine to prescription use in 1965, but non-medical use remained common. Amphetamine became a schedule II drug in the USA under the Controlled Substances Act in 1971.

The related compound methamphetamine, in its crystallized form, was first synthesized from ephedrine in Japan in 1920 by chemist Akira Ogata, via reduction of ephedrine using red phosphorus and iodine. The pharmaceutical Pervitin was a tablet of 3 mg methamphetamine that was available in Germany from 1938 and widely used in the Wehrmacht, but by mid-1941 it became a controlled substance, despite this new classification, methamphetamine and the cocaine-derivative referred to as "Codename D-IX" were distributed by military doctors across both the Western and Eastern theatres of war. During the course of the war over 200 million Pervitin pills were prescribed to Wehrmacht combatants.

In 1997 and 1998, researchers at Texas A&M University claimed to have found amphetamine and methamphetamine in the foliage of two Acacia species native to Texas, A. berlandieri and A. rigidula. Previously, both of these compounds had been thought to be human inventions. These findings have never been duplicated, and the analyses are believed by many biochemists to be the result of experimental error, and as such the validity of the report has come into question. Alexander Shulgin, one of the most experienced biochemical investigators and the discoverer of many new psychotropic substances, has tried to contact the Texas A&M researchers and verify their findings. The authors of the paper have not responded; natural amphetamine remains an unconfirmed discovery.

Performance-enhancing use

Adderall, an amphetamine mixture, is used by some college and high-school students as a study and test-taking aid. Amphetamine works by increasing energy levels, concentration, and motivation, thus allowing students to study for an extended period of time.

Amphetamine has been, and is still, used by militaries around the world. British troops used 72 million amphetamine tablets in the second world war and the RAF used so many that "Methedrine won the Battle of Britain" according to one report. American bomber pilots use amphetamine ("go pills") to stay awake during long missions. The Tarnak Farm incident, in which an American F-16 pilot killed several friendly Canadian soldiers on the ground, was blamed by the pilot on his use of amphetamine. A nonjudicial hearing rejected the pilot's claim.

Amphetamine is also used by some professional, collegiate and high school athletes for its strong stimulant effect. Energy levels are perceived to be dramatically increased and sustained, which is believed to allow for more vigorous and longer play. However, at least one study has found that this effect is not measurable. The use of amphetamine during strenuous physical activity can be extremely dangerous, especially when combined with alcohol, and athletes have died as a result, for example, British cyclist Tom Simpson.

Amphetamine use has historically been especially common among Major League Baseball players and is usually known by the slang term "greenies". In 2006, the MLB banned the use of amphetamine. The ban is enforced through periodic drug-testing. However, the MLB has received some criticism because the consequences for amphetamine use are dramatically less severe than for anabolic steroid use, with the first offense bringing only a warning and further testing.

Amphetamine was formerly in widespread use by truck drivers to combat symptoms of somnolence and to increase their concentration during driving, especially in the decades prior to the signing by former president Ronald Reagan of Executive Order 12564, which initiated mandatory random drug testing of all truck drivers and employees of other DOT-regulated industries. Although implementation of the order on the trucking industry was kept to a gradual rate in consideration of its projected effects on the national economy, in the decades following the order, amphetamine and other drug abuse by truck drivers has since dropped drastically. (See also Truck driver—Implementation of drug detection).

Detection in body fluids

Amphetamine is frequently measured in urine as part of a drug test, in plasma or serum to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized victims, or in whole blood to assist in the forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a case of sudden death. Techniques such as immunoassay may cross-react with a number of sympathomimetics drugs, so chromatographic methods specific for amphetamine should be employed to prevent false positive results. Chiral techniques may be employed to help distinguish the source of the drug, whether obtained legally (via prescription) or illicitly, or possibly as a result of formation from a prodrug such as lisdexamfetamine or selegiline. Chiral separation is needed to assess the possible contribution of l-methamphetamine (Vicks Inhaler) toward a positive test result.

Society and culture

From the 1960s onward, amphetamine has been popular with many youth subcultures in Britain (and other parts of the world) as a recreational drug. It has been commonly used by mods, skinheads, punks, goths, gangsters, and casuals in all night soul and ska dances, punk concerts, basement shows and fighting on the terraces by casuals.

The hippie counterculture was very critical of amphetamines due to the behaviors they cause; in an interview with the Los Angeles Free Press in 1965, beat writer Allen Ginsberg commented that "Speed is antisocial, paranoid making, it's a drag... all the nice gentle dope fiends are getting screwed up by the real horror monster Frankenstein speed freaks who are going round stealing and bad-mouthing everybody".

In literature

The writers of the Beat Generation used amphetamine extensively, mainly under the Benzedrine brand name. Jack Kerouac was a particularly avid user of amphetamine, which was said to provide him with the stamina needed to work on his novels for extended periods of time.

Scottish author Irvine Welsh often portrays drug use in his novels, though in one of his journalism works he comments on how drugs (including amphetamine) have become part of consumerism and how his novels Trainspotting and Porno reflect the changes in drug use and culture during the years that elapse between the two texts.

Amphetamine is frequently mentioned in the work of American journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Speed not only appears among the inventory of drugs Thompson consumed for what could broadly be defined as recreational purposes but also receives frequent, explicit mention as an essential component of his writing toolkit, such as in his "Author's Note" in Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72.

"One afternoon about three days ago showed up at my door with no warning, and loaded about forty pounds of supplies into the room: two cases of Mexican beer, four quarts of gin, a dozen grapefruits, and enough speed to alter the outcome of six Super Bowls. ... Meanwhile, with the final chapter still unwritten and the presses scheduled to start rolling in twenty-four hours . . . . unless somebody shows up pretty soon with extremely powerful speed, there might not be a final chapter. About four fingers of king-hell Crank would do the trick, but I am not optimistic."

In music

Many songs have been written about amphetamine, for example in the track entitled "St. Ides Heaven" from singer/songwriter, Elliott Smith's self-titled album. Semi Charmed Life by Third Eye Blind also references amphetamine. Another blatant example would be the song simply labelled "Amphetamine" by Alternative rock band Everclear, the song "20 Dollar nose bleed" by the Pop-rock band Fall Out Boy, and the song Headfirst For Halos by My Chemical Romance. It has also influenced the aesthetics of many rock'n'roll bands (especially in the garage rock, mod R&B, death rock, punk/hardcore, gothic rock and extreme heavy metal genres). Hüsker Dü, Jesus and Mary Chain's and The Who were keen amphetamine users early in their existence. Hollywood Undead references the drug as a negative effect in the song City off their breakout album Swan Songs. Land Speed Record is an allusion to Hüsker Dü's amphetamine use. Amphetamine was widely abused in the 1980s underground punk-rock scene. Punk-rock band NOFX have incorporated references to Amphetamines and other stimulants, the two most obvious being the song "Three on Speed" from the "Surfer" 8" LP (in reference to the three guys being on Amphetamine while recording the album), and earlier the album "The Longest Line" is in reference to a "line" of Amphetamine ready for insufflation. The Rolling Stones referenced the drug in their song "Can't You Hear Me Knocking" on the album Sticky Fingers ("Y'all got cocaine eyes / Yeah, ya got speed-freak jive now"). Lou Reed refers explicitly to the drug on his album Berlin, in the song "How Do You Think It Feels?". Reed's band The Velvet Underground, a creation of Andy Warhol's Factory Years, was fueled by amphetamines, as well as naming their second album White Light/White Heat after the drug and making reference to the song in "Sister Ray.". The Pulp song Sorted for E's & Wizz refers to British slang terms for ecstasy and amphetamines. English gothic rock band The Sisters of Mercy refers to the drug in their song "Amphetamine Logic" from their first album, First and Last and Always, and their singer Andrew Eldritch used amphetamines repeatedly. The Byrds referenced amphetamines in the 1968 song "Artificial Energy" on the album "The Notorious Byrd Brothers."

Many rock'n'roll bands have named themselves after amphetamine and drug slang surrounding it. For example Mod revivalists, The Purple Hearts named themselves after the amphetamine tablets popular with mods during the 1960s, as did the Australian band of the same name during the mid-1960s. The Amphetameanies, a ska-punk band, are also named after amphetamine, but also imitate its effects. Dexys Midnight Runners, of number one hit "Come On Eileen", are named after Dexedrine. Motörhead derived their name from the song of the same name, originally by Hawkwind where Ian "Lemmy" Kilmister was on bass before leaving to form Motörhead. Lemmy Kilmister is a long-term user of speed.

The Northern Soul scene, an offshoot of the mod scene, involved people taking amphetamines to keep dancing all night. One DJ, Roger Eagle, got out of the Northern Soul scene saying: "All they wanted was fast-tempo black dance music... too blocked on amphetamines to articulate exactly which Jackie Wilson record they wanted me to play."

In film

Producer David O. Selznick was an amphetamine user, and would often dictate long and rambling memos under the influence of amphetamine to his directors. The documentary Shadowing The Third Man relates that Selznick introduced The Third Man director Carol Reed to the use of amphetamine, which allowed Reed to bring the picture in below budget and on schedule by filming nearly 22 hours at a time.

The title of the 2009 movie Amphetamine plays on the double meaning of the word in Chinese - besides the name for the drug it also means 'isn't this his fate?' which figuratively ties to the movie's plot. The word is transliterated as 安 非 他 命 - "ān fēi tā mìng" - and as commonly happens with transliteration of non-Chinese terms each character has independent meaning as an individual unrelated word.

In mathematics

One of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, Paul Erdős, took amphetamines after the age of 58 until his death at the age of 83 (he had previously sustained himself on copious amounts of coffee). He took amphetamines despite the concern of his friends, one of whom (Ron Graham) bet him $500 that he could not stop taking the drug for a month. Erdős won the bet, but complained that during his abstinence mathematics had been set back by a month: "Before, when I looked at a piece of blank paper my mind was filled with ideas. Now all I see is a blank piece of paper." After he won the bet, he promptly resumed his amphetamine use.

Legal status

- In the United Kingdom, amphetamines are regarded as Class B drugs. The maximum penalty for unauthorized possession is five years in prison and an unlimited fine. The maximum penalty for illegal supply is 14 years in prison and an unlimited fine.

- In the Netherlands, amphetamine and methamphetamine are List I drugs of the Opium Law, but the dextro isomer of amphetamine is indicated for ADD/ADHD and narcolepsy and available for prescription as 5 and 10 mg generic tablets, and 5 and 10 mg gel capsules.

- In the United States, amphetamine and methamphetamine are Schedule II drugs, classified as CNS (central nervous system) stimulants. A Schedule II drug is classified as one that has a high potential for abuse, has a currently accepted medical use and is used under severe restrictions, and has a high possibility of severe psychological and physiological dependence.

- In Canada, possession of amphetamines is a criminal offence under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, with a maximum penalty for repeat offenders of fines of up to $2,000, imprisonment for up to one year, or both.

- In Australia, the dextro isomer of amphetamine is sold under the name dexamphetamine, and is a Schedule 8 controlled drug (available for certain indications with authority, illegal to possess otherwise).

Internationally, amphetamine is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Prodrugs

A number of substances have been shown to produce amphetamine and/or methamphetamine as metabolites, including amfecloral, amphetaminil, benzphetamine, clobenzorex, dimethylamphetamine, ethylamphetamine, famprofazone, fencamine, fenethylline, fenproporex, furfenorex, lisdexamfetamine, mefenorex, mesocarb, prenylamine, propylamphetamine, and selegiline, among others. These compounds may produce positive results for amphetamine on drug tests.

Derivatives

Amphetamine derivatives are a class of potent drugs that act by increasing levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the brain, inducing euphoria. The class includes prescription CNS drugs commonly used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is also used to treat symptoms of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and the daytime drowsiness symptoms of narcolepsy, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS).

Smuggling

213 kg of amphetamine worth 40 million AED (Nearly $11 million) was seized by the United Arab Emirate Drug combat authorities on 30 November 2011 from an Iranian ship that was supposed to deliver the consignment in Malaysia and made a port stop in Sharjah.

The Gulf News published on 30 November 2011, saying "This is the biggest drug bust of its kind in 2011 and the second big one in the last three years worldwide," said Dr. Wadia Maalouf, International expert at the United Nation's Drug and Crime office.

Notes and references

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- Miranda-G E, Sordo M, Salazar AM (2007). "Determination of amphetaminoe, methamphetamine, and hydroxyamphetamine derivatives in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and its relation to CYP2D6 phenotype of drug users". J Anal Toxicol. 31 (1): 31–6. PMID 17389081.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Craig Medical Distribution. "Drug Test FAQ | Craig Medical Distribution, Inc". Craigmedical.com. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Berman, SM.; Kuczenski, R.; McCracken, JT.; London, ED. (2009). "Potential adverse effects of amphetamine treatment on brain and behavior: a review". Mol Psychiatry. 14 (2): 123–42. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.90. PMID 18698321.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Nutt, D; King, LA; Saulsbury, W; Blakemore, C (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- Amphetamines. "Erowid Amphetamines Vault | Effects". Erowid.org. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Amphetamine; Facts | Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Research Foundation, Toronto Canada

- "Amphetamines | Better Health Channel". Betterhealth.vic.gov.au. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Dextroamphetamine (Oral Route)". MayoClinic.com. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Vitiello B (2008). "Understanding the risk of using medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with respect to physical growth and cardiovascular function". Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 17 (2): 459–74, xi. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.010. PMC 2408826. PMID 18295156.

- "Amphetamines | Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp". Merckmanuals.com. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Symptoms of Amphetamine withdrawal". WrongDiagnosis.com. 1 February 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "eMedTV | Dextroamphetamine Withdrawals". Sleep.emedtv.com. 5 March 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Dexedrine Information". Drug Abuse Help. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "''Amphetamine Disease Interactions". Drugs.com. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "ADDERALL XR capsule" (PDF). 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Check|first=value (help) - "Amphetamines: Drug Use and Abuse: Merck Manual Home Edition". Merck. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- McKetin R, McLaren J, Lubman DI, Hides L (2006). "The prevalence of psychotic symptoms among methamphetamine users". Addiction. 101 (10): 1473–8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sato M, Numachi Y, Hamamura T (1992). "Relapse of paranoid psychotic state in methamphetamine model of schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 18 (1): 115–22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hofmann FG. A handbook on drug and alcohol abuse: the biomedical aspects. 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W (2009). "Treatment for amphetamine psychosis (Review)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones S, Kornblum JL, Kauer JA (2000). "Amphetamine blocks long-term synaptic depression in the ventral tegmental area". J. Neurosci. 20 (15): 5575–80. PMID 10908593.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moore KE (1977). "The actions of amphetamine on neurotransmitters: a brief review". Biol. Psychiatry. 12 (3): 451–62. PMID 17437.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Del Arco A, González-Mora JL, Armas VR, Mora F (1999). "Amphetamine increases the extracellular concentration of glutamate in striatum of the awake rat: involvement of high affinity transporter mechanisms". Neuropharmacology. 38 (7): 943–54. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00043-X. PMID 10428413.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Drevets WC, Gautier C, Price JC (2001). "Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria". Biol. Psychiatry. 49 (2): 81–96. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01038-6. PMID 11164755.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wise, RA. "Brain reward circuitry and addiction." Program and abstracts of the American Society of Addiction Medicine 2003 The State of the Art in Addiction Medicine; 30 October – 1 November 2003; Washington, DC. Session

- ^ Sulzer D, Chen TK, Lau YY, Kristensen H, Rayport S, Ewing A (1995). "Amphetamine redistributes dopamine from synaptic vesicles to the cytosol and promotes reverse transport". J. Neurosci. 15 (5 Pt 2): 4102–8. PMID 7751968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21338876, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21338876instead. - ^ Kuczenski R, Segal DS (1997). "Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine". J. Neurochem. 68 (5): 2032–7. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052032.x. PMID 9109529.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Balance between dopamine and serotonin release modulates behavioral effects of amphetamine-type drugs". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1074: 245–60. Bibcode:2006NYASA1074..245R. doi:10.1196/annals.1369.064. PMID 17105921.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Johnson LA, Guptaroy B, Lund D, Shamban S, Gnegy ME (2005). "Regulation of amphetamine-stimulated dopamine efflux by protein kinase C beta". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (12): 10914–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413887200. PMID 15647254.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kahlig KM, Binda F, Khoshbouei H (2005). "Amphetamine induces dopamine efflux through a dopamine transporter channel". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (9): 3495–500. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.3495K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407737102. PMC 549289. PMID 15728379.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "A mechanism for amphetamine-induced dopamine overload". PLoS Biology. 2 (3): e87. 2004. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020087. PMC 368179.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7751968, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=7751968instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19409267, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19409267instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2268433, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2268433instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12388602, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12388602instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15955613, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15955613instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11487614, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11487614instead. - ^ Jones S, Kauer JA (1999). "Amphetamine depresses excitatory synaptic transmission via serotonin receptors in the ventral tegmental area". J. Neurosci. 19 (22): 9780–7. PMID 10559387.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hilber B, Scholze P, Dorostkar MM (2005). "Serotonin-transporter mediated efflux: a pharmacological analysis of amphetamines and non-amphetamines". Neuropharmacology. 49 (6): 811–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.008. PMID 16185723.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Florin SM, Kuczenski R, Segal DS (1994). "Regional extracellular norepinephrine responses to amphetamine and cocaine and effects of clonidine pretreatment". Brain Res. 654 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(94)91570-9. PMID 7982098.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Adderall". RxList. 4 October 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Amphetamine use in adolescence may impair adult working memory". Archived from the original on 10 November 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) -

Brussee, J. (1983). "A highly stereoselective synthesis of s(-)--2,2′-diol". Tetrahedron Letters. 24 (31): 3261–3262. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)88151-4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - WikiAnswers google cached page: 'Does Namenda memantine work in preventing tolerance to adderall ADD amphetamine type drugs?'

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A (2005). "Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review". Prog. Neurobiol. 75 (6): 406–33. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. PMID 15955613.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11723224, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11723224instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19364908, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19364908instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11459929, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11459929instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18310473, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18310473instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17234900, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17234900instead. - http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9076658

- Edeleano L (1887). "Ueber einige Derivate der Phenylmethacrylsäure und der Phenylisobuttersäure". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 20 (1): 616–622. doi:10.1002/cber.188702001142.

- Shulgin, Alexander (1992). "6 – MMDA". PiHKAL. Berkeley, California: Transform Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-9630096-0-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rasmussen N (2006). "Making the first anti-depressant: amphetamine in American medicine, 1929–1950". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 61 (3): 288–323. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrj039. PMID 16492800.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Iverson, Leslie. Speed, Ecstasy, Ritalin: the science of amphetamines. Oxford, New York. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Rasmussen, Nicolas (2008). "Ch. 4". On Speed: The Many Lives of Amphetamine. New York, New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7601-9.

- "Nazis Secret Weapon: They were all high". http://www.news.com.au. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - Clement B.A., Goff C.M., Forbes T.D.A. (1998). "Toxic amines and alkaloids from Acacia rigidula". Phytochemistry. 49 (5): 1377–1380. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(97)01022-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Clement B.A., Goff C.M., Forbes T.D.A. (1997). "Toxic amines and alkaloids from Acacia berlandieri". Phytochemistry. 46 (2): 249–254. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00240-9.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Ask Dr. Shulgin Online: Acacias and Natural Amphetamine". Cognitiveliberty.org. 26 September 2001. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Twohey, Megan (25 March 2006). "Pills become an addictive study aid". JS Online. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- De Mondenard, Dr Jean-Pierre: Dopage, l'imposture des performances, Chiron, France, 2000

- Grant, D.N.W.; Air Force, UK, 1944

- "Air force rushes to defend amphetamine use". The Age. 18 January 2003. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Yesalis, Charles E.; Bahrke, Michael (2005-12). "Anabolic Steroid and Stimulant Use in North American Sport between 1850 and 1980". Sport in History. 25 (3): 434–451. doi:10.1080/17460260500396251. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ National Collegiate Athletic Association (2006-01), NCAA Study of Substance Use Habits of College Student-Athletes (PDF), National Collegiate Athletic Association, pp. 2–4, 11–13, retrieved 2 December 2007

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Margaria, R; Aghemo, P.; Rovelli, E. (1 July 1964). "The effect of some drugs on the maximal capacity of athletic performance in man". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 20 (4): 281–287. doi:10.1007/BF00697020. PMID 14252788.

- Frias, Carlos (2 April 2006). "Baseball and amphetamines". Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Kreidler, Mark (15 November 2005). "Baseball finally brings amphetamines into light of day". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- Klobuchar, Jim (31 March 2006). "Can baseball make a clean sweep?". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) -

Associated Press (18 January 2007). "MLB owners won't crack down on 'greenies'". MSNBC.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Lund, Adrian K (1989). "Drug Use by Tractor-Trailer Drivers". Drugs in the Workplace: Research and Evaluation Data. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. pp. 47–67.

This study has provided the first objective data regarding the use of potentially abusive drugs by tractor-trailer drivers... Prescription stimulants, such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, and phentermine were found in 5 percent of the drivers , often in combination with similar but less potent stimulants, such as phenylpropanolamine. Nonprescription stimulants were detected in 12 percent of the drivers, about half of whom gave no medical explanation for their presence... One limitation of these findings is that 12 percent of the randomly selected drivers refused to participate in the study or provided insufficient urine and blood for testing; the distribution of drugs among these 42 drivers is unknown... Finally, the results apply to tractor-trailer drivers operating on a major east-west interstate route in Tennessee. Drug incidence among other truck-driver populations are unknown and may be higher or lower than reported here. (64)

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Verstraete AG, Heyden FV (2005). "Comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of six immunoassays for the detection of amphetamines in urine". J Anal Toxicol. 29 (5): 359–64. PMID 16105261.

- Paul BD, Jemionek J, Lesser D, Jacobs A, Searles DA (2004). "Enantiomeric separation and quantitation of (+/-)-amphetamine, (+/-)-methamphetamine, (+/-)-MDA, (+/-)-MDMA, and (+/-)-MDEA in urine specimens by GC-EI-MS after derivatization with (R)-(-)- or (S)-(+)-alpha-methoxy-alpha-(trifluoromethy)phenylacetyl chloride (MTPA)". J Anal Toxicol. 28 (6): 449–55. doi:10.1093/jat/28.6.449. PMID 15516295.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 9th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2011, pp. 85-88.

- Brecher, Edward M. (1972). "How speed was popularized". The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs. Schaffer Drug Library. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gyenis, Attila (1997). "Forty Years of On the Road 1957–1997". Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- Welsh, Irvine (10 August 2006). "Drug Cultures in Trainspotting and Porno". irvinewelsh.net. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- Carr, David (29 June 2008). "Fear and Loathing on a Documentary Screen". New York Times. pp. AR7. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Thompson, Hunter S. (1973). Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72. New York: Warner Books. pp. 15–16, 21. ISBN 0-446-31364-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Keith Rylatt and Phil Scott, Central 1179: The Story of Manchester's Twisted Wheel Club, BeeCool Publishing. 2001

- Memo From David O. Selznick, http://www.amazon.com/Memo-David-Selznick-Memorandums-Autobiographical/dp/0375755314

- Shadowing the Third Man, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0429086/

- Hill, J. Paul Erdos, Mathematical Genius, Human (In That Order)

- "Class A, B and C drugs". Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Trends in Methamphetamine/Amphetamine Admissions to Treatment: 1993–2003". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- "Straight Facts About Drugs & Drug Abuse". Health Canada. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2005. Retrieved 19 November 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Musshoff F (2000). "Illegal or legitimate use? Precursor compounds to amphetamine and methamphetamine". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 32 (1): 15–44. doi:10.1081/DMR-100100562. PMID 10711406.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cody JT (2002). "Precursor medications as a source of methamphetamine and/or amphetamine positive drug testing results". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine / American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 44 (5): 435–50. PMID 12024689.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Drevets, W; et al. (2001). "Amphetamine-Induced Dopamine Release in Human Ventral Striatum Correlates with Euphoria" (PDF). Psychiatry. 49: 81–96. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - Rang and Dale, Pharmacology

- Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM (2010). "The clinical toxicology of metamfetamine". Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 48 (7): 675–94. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.516752. ISSN 1556-3650. PMID 20849327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Nine arrested in biggest drug haul of the year". gulfnews.com. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

External links

- CID 5826 from PubChem (D-form—dextroamphetamine)

- CID 3007 from PubChem (L-form and D, L-forms)

- CID 32893 from PubChem (L-form—Levamphetamine or L-amphetamine)

- List of 504 Compounds Similar to Amphetamine (PubChem)

- EMCDDA drugs profile: Amphetamine (2007)

- Drugs.com - Amphetamine

- Asia & Pacific Amphetamine-Type Stimulants Information Centre

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Amphetamine

| Stimulants | |

|---|---|

| Adamantanes | |

| Adenosine antagonists | |

| Alkylamines | |

| Ampakines | |

| Arylcyclohexylamines | |

| Benzazepines | |

| Cathinones |

|

| Cholinergics |

|

| Convulsants | |

| Eugeroics | |

| Oxazolines | |

| Phenethylamines |

|

| Phenylmorpholines | |

| Piperazines | |

| Piperidines |

|

| Pyrrolidines | |

| Racetams | |

| Tropanes |

|

| Tryptamines | |

| Others |

|

| ATC code: N06B | |

| ADHD pharmacotherapies | |

|---|---|

| CNSTooltip central nervous system stimulants | |

| Non-classical CNS stimulants | |

| α2-adrenoceptor agonists | |

| Antidepressants | |

| Miscellaneous/others | |

| Related articles |

|

| Antiobesity agents/Anorectics (A08) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulants |

| ||||||

| Cannabinoid antagonists | |||||||

| GLP-1, GIP, and / or glucagon agonists | |||||||

| DACRAs | |||||||

| 5-HT2C receptor agonists | |||||||

| Absorption inhibitors | |||||||

| Uncouplers | |||||||

| Others | |||||||

| |||||||

| Adrenergic receptor modulators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 |

| ||||

| α2 |

| ||||

| β |

| ||||

| Dopamine receptor modulators | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1-like |

| ||||||

| D2-like |

| ||||||

| Sigma receptor modulators | |

|---|---|

| σ1 |

|

| σ2 |

|

| Unsorted |

|

| See also: Receptor/signaling modulators | |

| Human trace amine-associated receptor ligands | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAAR1 |

| ||||||||||

| TAAR2 |

| ||||||||||

| TAAR5 |

| ||||||||||

| References for all endogenous human TAAR1 ligands are provided at List of trace amines

| |||||||||||

| Phenethylamines | |

|---|---|

| Phenethylamines |

|

| Amphetamines |

|

| Phentermines |

|

| Cathinones |

|

| Phenylisobutylamines | |

| Phenylalkylpyrrolidines | |

| Catecholamines (and close relatives) |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

- Use dmy dates from August 2012

- Amphetamines

- Anorectics

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Bronchodilators

- Drugs acting on the cardiovascular system

- Euphoriants

- Stimulants

- German inventions

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Dopamine agonists

- Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- Serotonin receptor agonists

- Youth culture in the United Kingdom