This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Arildnordby (talk | contribs) at 23:32, 22 February 2013 (→Main Uses). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:32, 22 February 2013 by Arildnordby (talk | contribs) (→Main Uses)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Impale (disambiguation).

Impalement is the traumatic penetration of an organism by an elongated foreign object such as a stake, pole, or spear, and this usually implies complete perforation of the central mass of the impaled body. While the term may be used in reference to an accident, this article focuses on impalement as a form of execution. In addition, examples where impalement have been used within sacrificial customs, as a way of shaming the dead, or used as a superstitious means to prevent the dead from rising from the graves have been included.

Main Uses

The reviewed literature suggests that impalement across a number of cultures was regarded as a very severe punishment, as it was used particularly in response to "crimes against the state". Impalement is predominantly mentioned as punishment within the context of war, treason against "the fatherland", against some "cause" or as punishment for rebellion. As another martial example, soldiers found guilty of cowardice, or grave dereliction of duty were punished with impalement among Zulus. Disregard for the state's responsibility for safe roads and trade routes by committing highway robbery, violating state monopolies, or subverting standards for trade are also recorded as offenses where impalement was occasionally used as punishment. For example, visiting Egypt around 1660, Jean de Thévenot observed a man impaled for using false weights.

Several cases show that impalement was a technique used in extrajudicial, summary executions and in massacres, or in cases of institutional religious persecution. At various times and places, individual murderers have been punished with impalement, either by prescribed law, or in cases regarded as particularly heinous. A case in point is the old Bengali law code Arthashastra (composed between the 4th century BC and 200 AD), where the following crimes were punishable by impalement, or suka: murder with violence, infliction of undeserved punishment, spreading of false reports, highway robbery, and theft of or wilful injury to the king's horse, elephant or chariot. As a punishment for severe cases of religious crimes impalement was on occasion used in different parts of the world, and there are a few cases of human sacrifice by impalement. Some instances of impalement prescribed by law for adultery are also noted.

Spanish, Dutch and Portuguese colonialists are reported to have used impalement to subjugate indigenous tribes, or as a punishment meted out to slaves.

Methods

Impalement typically involves the body of a person being pierced through by a long stake, but sharp hooks, either fully penetrating the body, or becoming embedded in it, have also been used.

The impalement could be in the frontal-to-dorsal direction, that is, from front (for example, through abdomen, chest or directly through the heart) to back or vice versa

Alternatively, impalement could be in the longitudinal or vertical direction, along the body length. The longitudinal penetration could be through the rectum, through the vagina, or through a wound opened specifically for the occasion, such as through the perineum. The penetrating object may exit from a wound, typically in the area between the neck and the shoulders.

When the impaling instrument was inserted into a lower orifice/wound, one might, as the traveler Jean de Thevenot observed, secure the victim in the prone position; the stake would then be held in place by one of the executioners, while another would hammer the stake inward. The stake was then planted in the ground, and the impaled victim hoisted up to a vertical position.

Impalement leads to a painful death, sometimes taking days.

Less usual methods of impalement have been alleged, for example, direct cranial impalement by driving a long nail or spike into a victim's head. The Tunisian Arab merchant Muḣammad ibn ʻUmar (1789-?) made extensive travels in his time, and relates a story of how a very unfortunate Jew is to have met his end: "A Sultan of Morocco once put a Jew in a barrel, the inside of which bristled with nails, and ordered it to be rolled down a hill"

From time to time, it is recorded that impalement was aggravated beyond that punishment, in that the impaled individual also was roasted over a fire, for example.

In addition, impalement as a form of post mortem indignity is recorded.

Gaunching

de Tournefort, travelling on research in the Levant 1700-02, observed both ordinary longitudinal impalement, but also a method called "gaunching", in which the condemned is hoisted up by means of a rope over a bed of sharp metal hooks. He is then released, and depending on how the hooks enter his body, he may survive in impaled condition for a few days. 40 years earlier than de Tournefort, de Thevenot described much the same process, adding it was seldom used, because it was regarded as too cruel

Mass executions and spectacles of horror

Occasionally, impalement has been an element in grand spectacles of horror, in which a large number are executed, often with other types of grievous punishments recorded as well. Some examples are:

The 6th century BC Cyrenaican (modern eastern Libya, bordering Egypt) Queen Pheretima took revenge on those who had conspired to murder her son Arcesilaus III: She impaled all the men around the city walls, and "affixed near them the breasts of their wives which she ordered to be cut off for that purpose".

In the wake of suppressing the Babylonian revolt in 522 BC, Persian king Darius the Great had 3000 of the leading citizens impaled.

Cassius Dio relates the following story of how Romans, and those collaborating with them were massacred during Boudicca's revolt:

"Those who were taken captive by the Britons were subjected to every known form of outrage. The worst and most bestial atrocity committed by their captors was the following. They hung up naked the noblest and most distinguished women and then cut off their breasts and sewed them to their mouths, in order to make the victims appear to be eating them; afterwards they impaled the women on sharp skewers run lengthwise through the entire body."

In ancient Tamil Nadu, in present-day India, impaling was referred to as Kazhuvetram. A notorious episode from Tamil Nadu, under the old Pandyan Dynasty, ruling from 500 BC- 1500 AD, the 7th century King Koon Pandiyan had 8000 Jains impaled alive. This act is still commemorated in "lurid mural representations" in several Hindu temples in Tamil Nadu. In that particular case, the Jains were massacred for blasphemy, for having taken the name of Shiva in vain.

In 1514, the so-called Dozsa Rebellion broke out in Hungary, under leadership of György Dozsa, starting out as a protest against perceived willingness in the Hungarian nobility to compromise with the Turks, but evolving into a general massacre on local magnates. Amongst other atrocities, the rebels are said to have impaled alive the bishop of Csanad, Niklas Scaki. The suppression of the revolt was hardly less gory: Several of the peasant supporters were impaled (some roasted), and Dozsa himself was bound to an iron throne and crowned with a glowing crown. Thus roasted, his remaining supporters were forced to eat parts of him.

The Mughal emperor Jahangir made his rebellious son Prince Khusrau Mirza ride an elephant down a street lined with stakes on which the rebellious prince's supporters had been impaled alive. In his purported memoirs, Jahangir writes:

"In the course of the same Thursday I entered the castle of Lahour, where I took up my abode in the royal pavilion built by my father on this principal tower, from which to view the combats of elephants. Seated in the pavilion, having directed a number of sharp stakes to be set up in the bed of the Rauvy, I caused the seven hundred traitors who had conspired with Khossrou against my authority to be impaled alive upon them. Than this there cannot exist a more excruciating punishment, since the wretches exposed frequently linger a long time in the most agonizing torture, before the hand of death relieves them; and the spectacle of such frightful agonies must, if any thing can, operate as a due example to deter others from similar acts of perfidy and treason towards their benefactors."

Other Historical Uses

Archaic age/Antiquity

The earliest known use of impalement as a form of execution occurred in civilizations of the Ancient Near East. For example, the Code of Hammurabi, promulgated about 1772 BC by the Babylonian king Hammurabi specifies impaling for a woman who killed her husband for the sake of another man. Evidence by carvings and statues is found as well, for example from Neo-Assyrian empire. A peculiarity about the Assyrian way of impaling was that the stake was "driven into the body immediately under the ribs", rather than along the full body length.

In the Bible, II Samuel 21:9, we read

- “And they handed them over to the Gibeonites, and they impaled them ויקיעם on the mountain before YHVH, and all seven of them fell together. And they were killed in the first days of the harvest, at the beginning of the barley harvest.”

In ancient Rome, the term "crucifixion" could also refer to impalement. This derives in part because the term for the one portion of a cross is synonymous with the term for a stake, so that when mentioned in historical sources without specific context, the exact method of execution, whether crucifixion or impalement, can be unclear.

Africa

Thomas Shaw, who was chaplain for the Levant Company stationed at Algiers during the 1720s, differentiates between punishments meted out to different population groups, impalement primarily being used as a form of capital punishment for Arabs and Moors:

"When a Jew or a Christian slave, or subject is guilty of murder, or any other capital crime, he is carried without the gates of the city, and burnt alive: but the Moors and Arabs are either impaled for the same crime, or else they are hung up by the neck, over the battlements of the city walls, or else they are thrown upon the chingan or hooks that are fixed all over the walls below, where sometimes they break from one hook to another, and hang in the most exquisite torments, thirty or forty hours. The Turks are not publickly punished, like other offenders. Out of respect to their characters, they are always sent to the house of the Aga, where, according to the quality of the misdemeanor, they are bastinadoed or strangled."

60 years later than Shaw, around 1789 in Algiers, Johann von Rehbinder notes that throwing people on hooks, the "chingan" mentioned by Shaw, is a wholly discontinued practice in Algiers, and that burning of Jews had not occurred during his residence there.

Americas

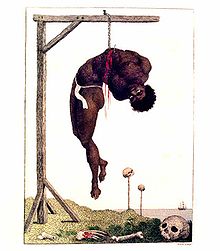

A particular technique devised by the Dutch overlords in Suriname was to hang a slave from the ribs. John Gabriel Stedman stayed there from 1772–77 and described the method as told by a witness:

"Not long ago, (continued he) I saw a black "man suspended alive from a gallows by the ribs, between which, with a knife, was first made an incision, and then clinched an iron hook with a chain: in this manner he kept alive three days, hanging with his head "and feet downwards, and catching with his tongue the "drops of water (it being in the rainy season) that were "flowing down his bloated breast. Notwithstanding all this, he never complained, and even upbraided a negro "for crying while he was flogged below the gallows, by calling out to him: "You man ?—Da boy fasy? Are you a man? you behave like a boy". Shortly after which he was knocked on the head by the commiserating sentry, who stood over him, with the butt end of his musket"

Asia

- Syria

Reportedly, members of the Alawite sect centered around Latakia in Syria had a particular aversion towards being hanged, and the family of the condemned was willing to pay "considerable sums" to ensure their relation was impaled, instead of being hanged. As far as Burckhardt could make out, this attitude was based upon the Alawites' idea that the soul ought to leave the body through the mouth, rather than leave it in any other fashion.

- Arabia

In 1838, Faisal bin Turki bin Abdullah Al Saud was ousted from the throne by Egyptian intrigues, and Khalid ibn Saud from the senior Saudi line was installed as pasha. He, however, became deeply hated for introducing punishments like impaling in the Nejd, and in 1840, he was replaced by Abdullah ibn Thuniyyan. If anything, the new ruler intensified the use of impaling and became even more hated than Khalid, preparing the takeover in 1843 by Faisal yet again.

- Vietnam

During the Vietnam War of the late 1960s, one account alleges that a village headman in South Vietnam who cooperated in some way with the South Vietnamese Army or with U.S. soldiers might have been impaled by local Viet Cong as a form of punishment for alleged collaboration. The method of impalement was alleged to have been the insertion of a sharpened stake through the anus; the stake was then supposedly planted vertically in the ground in view of his village. The victim was allegedly tortured and humiliated by complete castration, with the amputated genitalia being forced into his mouth. Another account alleges that the pregnant wife of a village headman was vertically impaled. There is also an allegation from the Vietnam War of coronal cranial impalement. In this case, a bamboo stake was supposedly thrust into the victim's ear and driven though the head until it emerged from the opposite ear opening. The act was allegedly perpetrated on three children of a village chief near Da Nang.

Impalement and other methods of torture were intended to intimidate civilian peasants at a local level into cooperating with the Viet Cong or discourage them from cooperating with the South Vietnamese Army or its allies. The main culprits for the use of impalement appear to be members of the Viet Cong of South Vietnam. No allegations have been made against soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), nor is there any evidence that either the NVA or the government in Hanoi ever condoned its use.

- Japan

Impalement was only occasionally used by samurai leaders during the Age of Warring States. Early in 1561, the allied forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga defeated the army of the Imagawa clan in western Mikawa province, encouraging the Saigo clan of east Mikawa, already chafing under Imagawa control, to defect to Ieyasu's command. Incensed at the rebellious Saigo clan, Imagawa Ujizane entered the castle-town of Imabashi, arrested Saigo Masayoshi and twelve others, and had them vertically impaled before the gate of Ryuden Temple, near Yoshida Castle. The deterrent had no effect, and by 1570, the Imagawa clan was stripped of its power.

Europe

- England, Edward II and shaming of suicides

It has long been believed that Edward II (1284-1327) was impaled by a heated poker thrust into his anus. This is, for example, contained in Christopher Marlowe's play Edward II (c. 1592). That story of Edward II's death can possibly be traced back to the late 1330s; however, the very earliest accounts of Edward's demise do not corroborate impalement, but speak instead of death by illness or suffocation. It is generally accepted by historians that he was murdered by an agent of his wife, Isabella, on 11 October 1327 in Berkeley Castle.

Not formally abolished until 1823, suicide victims and anyone killed during the commission of a crime could be punished post mortem with impalement. The law designated these deaths as felo de se ("felony against the self") and declared the dead person's movable property forfeit to the Crown (but not his lands). The body was buried at an unconsecrated location and early ecclesiastical law, like that of King Edgar in 967, forbade celebrating mass for the soul, nor commit his body to the ground with hymns or other rites of "honourable sepulture". The burial location was usually at a crossroads or highway. In some locations, a stake was driven through the corpse's heart. Following William Blackstone's reasoning, Moore is explicit upon that public shaming of the self-murderer is an important part of this tradition:

"By virtue of this authority the body of the self-murderer is cast with the burial of a dog into an hole dug in some public highway, which fulfils the law in this point. But in some places an additional (though not an enjoined) ignominy is practised, which consists in driving a stake through the body, and also inscribing the name and crime on a board above—" as a dreadful memorial to every passenger, how "he splits on the rock of self-murder.""

- Holy Roman Empire and Switzerland, custom of live burial+impalement

In the Holy Roman Empire, there existed a curious execution method of combined premature burial and impalement. While article 131 in the 1532 Constitutio Criminalis Carolina recommended that women guilty of infanticide should be drowned, the law code allowed for, in particularly severe cases, that the old punishment could be implemented: that is, the woman would be buried alive, and then a stake would be driven through her heart. Cases from the 15th/ early 16th century show that not only women found guilty of infanticide could be punished in this manner, but also women guilty of theft.

In some Landrechte and city statutes, like that for Husum in 1608, live burial and impalement is prescribed for parents who murder their children, or vice versa. Dieter Furcht speculates that the impalement was not so much to be regarded as an execution method, but as a way to prevent the condemned to become an avenging, undead Wiedergänger.

While it seems that execution by impalement following live burial was primarily a punishment for female criminals, it is also attested for rapists of virgins. In one description, the rapist was placed in an open grave, and the rape victim was ordered to make the three first strokes on the stake herself; the executioners then finishing the impalement procedure.

An odd case of impalement occurred in Zurich in 1465, for a man who had sexually violated 6 girls between the ages four and nine. His clothes were taken off, and he was placed on his back. His arms and legs were stretched out, each secured to a pole. Then a stake was driven through his navel down into the ground. Thereafter, people left him to die. Throughout the 400 years 1400-1798, this is the only known execution by impalement in Zürich, out of 1445 recorded executions.

- Wallachia, the case of Dracula

During the 15th century, Vlad III, Prince of Wallachia, is credited as the first notable figure to prefer this method of execution during the late medieval period, and became so notorious for its liberal employment that among his several nicknames he was known as Vlad the Impaler. After being orphaned, betrayed, forced into exile and pursued by his enemies, he retook control of Wallachia in 1456. He dealt harshly with his enemies, especially those who had betrayed his family in the past, or had profited from the misfortunes of Wallachia. Though a variety of methods was employed, he has been most associated with his use of impalement. The liberal use of capital punishment was eventually extended to Saxon settlers, members of a rival clan, and criminals in his domain, whether they were members of the boyar nobility or peasants, and eventually to any among his subjects that displeased him. Following the multiple campaigns against the invading Ottoman Turks, Vlad would never show mercy to his prisoners of war. The road to the capital of Wallachia eventually became inundated in a "forest" of 20,000 impaled and decaying corpses, and it is reported that an invading army of Turks turned back after encountering thousands of impaled corpses along the Danube River. Woodblock prints from the era portray his victims impaled from either the frontal or the dorsal aspect, but not vertically.

- Russia, tradition of rebellion and suppression thereof

In medieval Russia impalement in its traditional way was sometimes used as a punishment for some serious crimes or, more commonly, for treason. In particular, there are some evidences of this penalty being used during the reign of Ivan the Terrible. For example, the Elizabethan diplomat and traveller Jerome Horsey notes the gruesome end of one nobleman, and the no less appalling fate of his mother

Faced with serious revolts, the Czars' suppressions could be extremely bloody. For example, the following is told of how Stenka Razin's rebellion was crushed:

"In November, 1671, Astrakhan, the last bastion of the rebels, fell. The participants of the revolt were subject to severe repressions. Trained troops hunted down exhausted and fleeing rebels, who were impaled on stakes, nailed to boards, torn to shreds, or flogged to death. 11 thousand people were executed in the town of Arzamas alone."

One notable execution outside wartime was recorded in 1718, when first Russian emperor Peter the Great ordered Stepan Glebov, the lover of Peter's ex-wife Eudoxia Lopukhina, to be impaled publicly as a traitor. Just a few years later, in 1722, when Peter the Great demanded an oath of allegiance from his subjects, tumults broke out in the little Siberian town Tara, and 700 men are said to have been impaled alive in one day.

In 1739, a peasant conceived the idea that he was, actually, Alexei Petrovitch, the son of Peter the Great, who had died in 1718 in dismal prison conditions on his father's suspicion he was trying to supplant him. The peasant in 1739 did not get much of a following, but he earned for himself the punishment of being impaled alive for his attempt at the crown.

According to some sources, punishments like impalement through the side and hanging people from the ribs were first discontinued under Empress Elizabeth (reign 1741-62).

That attitudes towards impalement as punishment had changed considerably in imperial circles by the latter half of the 18th century is readily seen in the aftermath of the 1774-75 Pugachev's rebellion. While the rebels impaled the governor of Dmitrefsk in 1774, in addition to the astronomer Georg Moritz Lowitz, Pugachev himself was merely beheaded.

Byzantine Empire

Impalement was used by the Byzantine Empire during its existence against various groups. Deserted soldiers would be thrown to wild animals or impaled. Enemy soldiers could also be impaled this happened to a part of captured Saracen raiders in 1035, they were impaled along the coastline from Adramytion to Strobilos. In 880 the crews and soldiers of some Byzantine ships who deserted during an Arab raid in southern Greece were paraded with ignominy through Constantinople and impaled. Emperor Basil II impaled captured rebel commanders in 989. At the beginning of 1185 emperor Andronikos I Komnenos stoned and impaled two relatives of Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire used impalement during the last Siege of Constantinople in 1453, though possibly earlier. Impalement seems to have been particularly used relative to those perceived to be rebels, during some of the more brutal repressions of nationalistic movements, or reprisals following insurrections in Greece, other countries of Southeast Europe Highway robbers were still impaled into the 1830s, but one source says the practice was rare by then. The reviewed literature has failed to provide examples of either robbers or rebels impaled by Ottoman authorities after 1835.

Tales and anecdotes concerning swift and harsh Ottoman justice for comparatively trivial offenses abound. For example, in 1632, under Murad IV (r.1623-40), a hapless interpreter in a fierce dispute between the French ambassador and Ottoman authorities (the French were accused of bringing a Muslim woman on board a ship) was impaled alive for faithfully translating the insolent words of the ambassador. Furthermore, Murad IV sought to ban the use of tobacco, and reportedly impaled alive a man and a woman for breaking the law, the one for selling tobacco, the other for using it.

During the Ottoman rule of Greece, impalement became an important tool of psychological warfare, intended to put terror into the peasant population. By the 18th century, Greek bandits turned guerrilla insurgents (known as klephts) became an increasing annoyance to the Ottoman government. Captured klephts were often impaled, as were peasants that harbored or aided them. Victims were publicly impaled and placed at highly visible points, and had the intended effect on many villages who not only refused to help the klephts, but would even turn them in to the authorities. The Ottomans engaged in active campaigns to capture these insurgents in 1805 and 1806, and were able to enlist Greek villagers, eager to avoid the stake, in the hunt for their outlaw countrymen.

The agony of impalement was, on occasion, compounded with being set over a fire, the impaling stake acting as a spit, so that the impaled victim might be roasted alive. Among other atrocities, Ali Pasha, an Albanian-born Ottoman noble who ruled Ioannina, had rebels, criminals, and even the descendants of those who had wronged him or his family in the past, impaled and roasted alive. For example, Thomas Smart Hughes, visiting Greece and Albania in 1812-13, says the following about his stay in Ioannina:

"Here criminals have been roasted alive over a slow fire, impaled, and skinned alive; others have had their extremities chopped off, and some have been left to perish with the skin of the face stripped over their necks. At first I doubted the truth of these assertions, but they were abundantly confirmed to me by persons of undoubted veracity. Some of the most respectable inhabitants of loannina assured me that they had sometimes conversed with these wretched victims on the very stake, being prevented from yielding to their torturing requests for water by fear of a similar fate themselves. Our own resident, as he was once going into the serai of Litaritza, saw a Greek priest, the leader of a gang of robbers, nailed alive to the outer wall of the palace, in sight of the whole city."

During the Greek War of Independence (1821–1832), Athanasios Diakos, a klepht and later a rebel military commander, was captured after the Battle of Alamana (1821), near Thermopylae, and after refusing to convert to Islam and join the Ottoman army, he was impaled, and died after three days. Diakos became a martyr for a Greek independence and was later honored as a national hero.

One of the worst atrocities with Greeks as perpetrators was the massacre following the Siege of Tripolitsa in October 1821, with several thousands massacred, several impaled and roasted.

The "bamboo torture"

A recurring horror story on many websites and popular media outlets is that Japanese soldiers during World War II inflicted "bamboo torture" upon prisoners of war. The victim was supposedly tied securely in place above a young bamboo shoot. Over several days, the sharp, fast growing shoot would first puncture, then completely penetrate the victim's body, eventually emerging through the other side. The cast of the TV program MythBusters investigated bamboo torture in a 2008 episode and found that a bamboo shoot can penetrate through several inches of ballistic gelatin in three days. For research purposes, ballistic gelatin is considered comparable to human flesh, and the experiment thus supported the viability of this form of torture, if not its historicity. In her memoir "Hakka Soul", the Chinese poet and author Chin Woon Ping mentions the "bamboo torture" as one of those tortures the locals believed the Japanese performed on prisoners.

This tale of using live trees impaling persons as they grow is, however, not confined to the context of WW2 and the Japanese as torturers, but was recorded in the 19th century as an allegation Malays used against the Siamese after the Siamese invasion of Kedah in 1821. Amongst other alleged punishments, the sprout of the nipah palm was used in the manner of a "bamboo torture".

Cultural references

In classic European folklore, it was believed that one method to "kill" a vampire, or prevent a corpse from rising as a vampire, was to drive a wooden stake through the heart before interment. In one story, an Istrian peasant named Jure Grando died and was buried in 1656. It was believed that he returned as a vampire, and at least one villager tried to drive a stake through his heart, but failed in the attempt. Finally, in 1672, the corpse was decapitated, and the vampire terror was put to rest. The idea that the vampire "can only be slain with a stake driven through its heart has been a mainstay of European fiction". For example, the TV-series Buffy The Vampire Slayer incorporates that idea.

The 1980 Italian film, Cannibal Holocaust, directed by Ruggero Deodato, graphically depicts impalement. The story follows a rescue party searching for a missing documentary film crew in the Amazon Rainforest. The film's depiction of indigenous tribes, death of animals on set, and the graphic violence (notably the impalement scene) brought on a great deal of controversy, legal investigations, boycotts and protests by concerned social groups, bans in many countries (some of which are still in effect), and heavy censorship in countries where it has not been banned. The impalement scene was so realistic, that Deodato was charged with murder at one point. Deodato had to produce evidence that the "impaled" actress was alive in the aftermath of the scene, and had to further explain how the special effect was done: the actress sat on a bicycle seat mounted to a pole while she looked up and held a short stake of balsa wood in her mouth. The charges were dropped.

A graphic description of the vertical impalement of a Serbian rebel by Ottoman authorities can be found in Ivo Andrić's novel The Bridge on the Drina. Andrić was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for the whole of his literary contribution, though this novel was the magnum opus.

In stage magic, the illusion of impalement is a popular feat of magic that appears to be an act of impalement.

Other cultures than European ones also exhibit tales and myths related to impalement:

In the Hindu Draupadi cult, impalement, of animals, demons and humans is a recurring motif within legends and symbolic re-enactments during holidays/festivals.

In the Buddhist conception of the eight Hells, as John Bowring relates from Siam, those consigned for the Sixth Hell are impaled on spits and roasted. When well roasted, enormous dogs with iron teeth devour them. But, the damned are reborn, and must relive this punishment for 16000 years, over and over again.... Another tale popular in Siam was about Devadatta,a wily antagonist to Buddha seeking to undermine Gautama's position among his followers. For this crime, Devadatta was sent off into the very deepest Hell, the Avici, being impaled on three great iron spears in a sea of flames.

In Bengal, tales existed about a certain Bhava Chandra, who is to have been a king in the Pala Empire, and his equally foolish minister. They are a pair not unlike the Wise Men of Gotham, being bereft of common sense as a result of a curse laid upon them. In their last judgment, they had condemned two robbers to be impaled, but when the robbers began quarreling about who should get impaled on the longest pole, Bhava Chandra and his minister became deeply intrigued. The robbers told them that whoever died on the longest pole would be reincarnated as the ruler of the Earth, while the other would become his minister. Thinking it unseemly that two mere robbers should gain such a high position in their next life, Bhava Chandra chose to impale himself on the longest pole, while his minister happily chose to die on the shorter.

Animals

The shrike is a notable example among birds of predatory impalement. To kill its prey, a shrike will pick up an insect or a small vertebrate (mouse or lizard), and impale it on a thorn or other sharp projection. With its prey immobilized and dying, the shrike can feed with little trouble of the prey's escape. This same behavior of impaling insects serves as an adaptation to eating the toxic lubber grasshopper (Romalea guttata). The bird waits for 1–2 days for the toxins within the grasshopper to degrade, and then can eat it.

The reviewed literature does not record any culturally sanctioned use of humans using intentionally prolonged impalement, as punishment or utility, against live animals. Animals have been hunted with so-called "primitive weapons", such as spears, atlatl darts, or arrows, though impalement in these cases is incidental to the kill, and the animal is usually despatched as quickly as possible.

In earlier times, it is reported that pit traps, with a stake in the bottom, and a chained dog as bait was used "in all parts of India" and the Malay archipelago to catch man eaters:

"Tigers are frequently caught in traps—the most common is the pit trap which is used in all parts of India. A deep pit is dug and the bottom staked with sharp pointed staves. The mouth of the pit is concealed by branches and leaves and the bait (a dog generally) is tied to a bar over the centre. The tiger in prowling about discovers the bait, naturally springs at it and alights on the stakes, he is often pierced through by them—if not he is easily dispatched with long spears."

Although live impalement does not seem to have been used much by humans as a means of punishment or utility, impaling animals alive as a sacrificial custom is well attested for several cultures. For example, according to Pliny the Elder, it was an annual rite in Rome to impale a dog alive on an elderberry branch. Furthermore, the 14th century Muslim traveler Ibn Batuta records a Mongol tradition of sacrificing horses by means of impalement when a great Khan died:

"With him they placed all the gold and silver vessels he had in his house,' together with four female slaves, and six of his favourite Mamluks, with a few vessels of drink. They were then all closed up, and the earth heaped upon them to the height of a large hill. They then brought four horses, which they pierced through at the hill, until all motion in them ceased; they then forced a piece of wood into the hinder part of the animal till it came out at his neck, and this they fixed in the earth, leaving the horses thus impaled upon the hill."

In arthropodology, and especially its subfield entomology, captured arthropods and insects are routinely killed and prepared for mounted display, whereby they are impaled by a pin to a portable surface, such as a board or display box made of wood, cork, cardboard, or synthetic foam. The pins used are typically 38 mm long and 0.46 mm in diameter, though smaller and larger pins are available. Impaled specimens of insects, spiders, butterflies, moths, scorpions, and similar organisms are collected, preserved, and displayed in this manner in private, academic, and museum collections around the world.

See also

- Impalement arts

- Iron maiden

- Penetrating trauma

- Punishment

- Shrike: a bird that impales its prey on thorns.

Quotations and explanatory notes

- a. "Impaling is also a very ordinary Punishment with them, which is done in this manner. They lay the Malefactor upon his Belly, with his Hands tied behind his Back, then they slit up his Fundament with a Razor, and throw into it a handful of Paste that they have in readiness, which immediately stops the Blood \ after that they thrust up into his Body a very long Stake as big as a Mans Arm, sharp at. the point and tapered, which they grease a little before; when they have driven it in with a Mallet, till it come out at his Breast, or at his Head or Shoulders, they lift him up, and plant this Stake very streight in the Ground, upon which they leave him so exposed for a day. One day I saw a Man upon the Pale, who was Sentenced to continue-so for three Hours alive/ and that he might not die too soon, the Stake was not thrust up far enough to come out at any part of his Body, and they also put a stay or rest upon the Pale, to hinder the weight of his body from making him sink down upon it, or the point' of it from piercing him through, which would have presently killed him: In this manner he was left for some Hours, (during which time he spoke) and turning from one side to another, prayed those that passed by to kill him, making a thousand wry Mouths and Faces, because of the pain be suffered when he stirred himself, but afeer Dinner the Basha sent one to dispatch him j which was easily done, by making the point of the Stake come out at his Breast, and then he was left till next Morning, when he was taken down, because he stunk horridly."

- b. "The Gaunch is a sort of Estrapade usually set up at the City-Gates: The Executioner lifts up the Criminal by means of a Pully, and then letting go the Rope, down falls the Wretch among a parcel of great Iron Flesh-hooks; which give him a quick or lasting Misery, as he chances to light: in this condition they leave them. Sometimes they live two or three days, and will ask for a Pipe of Tobacco, while their Comrades are cursing and blaspheming like Devils. A Bashaw passing by one of these places in Candia, an Offender that was hanging on the Gaunch, calls out to him, with a sneer, "Good my Lord! since you are so charitable according to your Law, be so kind as to shoot me through the head, to put an end to this Tragedy."

- c. Note: Woodblock print in Wallachia paragraph; no textual cases of dorsal-to-front have been reviewed

- d. Note: Although some illustrations provide image of the stake protruding from the mouth, like the image in the lead section, no such actual cases have been found within the literature reviewed.

- h. "Knez Borris Telupa, a great favorett of that tyme,' being' discovered to be a treason worcker ' traytor' against the emperor, and confederatt with the discontented nobillitie, was drawen upon a longe sharpe made stake, soped to enter' so made as that it was thrust into' his fundament thorrow his bodye, which came owt at his neeck ; upon which he languished in horable paine for fiften howres alive, and spake unto his mother, the Duches, brought to behold that wofull sight. And she, a goodly matronlye weoman, upon like displeasure, geaven to 100 gunners, whoe defiled her to deathe one after the other; her bodye, swollen and lieinge naked in the place, comanded his hunstsmen to bringe their hongrie hounds to eat and devouer her flesh and bones, dragged everiewher.

- i. Explanatory note: Either Ibn Battuta or Samuel Lee is using this term in a colloquial sense. "Mameluke" did not merely designate a member of the specific slave soldier aristocracy in Egypt (the technically precise meaning of the term), but was used to designate "slave soldier"/body guard in general

- j. Explanatory note:(The definition of יקע (YaQ`a) in Strong’s: “a prim. primitive root; prop. properly to sever oneself, i.e. (by impl. implication) to be dislocated; fig. to abandon; causat. causatively to impale (and thus allow to drop to pieces by rotting):- be alienated, depart, hang (up), be out of joint. The seven sons of Saul, mentioned here, are represented as a sacrifice required by God, to make an atonement for the sin of Saul. Till I get farther light on the subject, I am led to conclude that the whole chapter is not now what it would be coming from the pen of an inspired writer; and that this part of the Jewish records has suffered much from rabbinical glosses, alterations, and additions.” Clarke, 1831, p. II 267)

References

- Arson case by Turk in 1834 on Egyptian war ship: Yates (1843), p.20 Impalement only for extreme cases, Scott (1837),p.115

- 1670s civil war Hungary Schimmer (1847),p.72. 1813 On some 300 Wahhabi prisoners of wars promised mercy by Egyptian/Ottoman opponents:Burckhardt (1831)p.322-323 Afghan-Persian conflict in the 1720s Krusinski (1840)p.111-1121824, Burmese retreating soldiers on some 40 Assamese Buckingham (1826)p.243 1799, Naples, anarchic conditions Vidler(1799) p.256 1806 Calabrian Insurrection on French and sympathizers GvG (1816) p.110 1806 Lagonegro orders from French colonel Colletta (1858)p.20

- On "defection to the Turks" i) 1676 5 suspected arsonists in impaled alive in Upper Hungary, reportedly sent out by the Turks Feige(1694), p.312 ii)In 1697 Venetians on 20 soldiers caught defecting Rhodes(1697), p.420iii) Late 1739 Austrian case :de Waldinutzy (1772) p.477,column 1 1639 Kingdom of Kandy impalement of some 50 natives on treason allegation De Silva (1988) p.53 1735 Corsican case of "clandestine correspondence" Ackers (1735)p.50,column 1 As punishment for high treason in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 14th-18th centuries i) Generally, see: Tazbir, Janusz (1993), Sława i niesława Kostki-Napierskiego (in Polish) ii) Specifically, see for example, a) in 1635 of Ivan Sulyma Gifford (1863) p.468 and b) 1768, Ivan Gonta Harmsen (1770) p.143 During the 17th century, Swedish impalement of pro-Danish guerrilla resistance known as Snapphanes Åberg, Alf (1951), Snapphanarna (in Swedish), Stockholm: LTs Förlag

- The Hohenstaufen takeover of Sicily in 1194 von Imhof (1723), p.439 In 1705, alleged plot against the king and queen of Spain discovered, at least 7 impaled alive Luttrell (1857), p.565 Morocco in general for rebellion, see for 1720s Braithwaite (1729) p.366 Specific Morocco case 1705, some 300 rebels were impaled alive, in batches of 50 Rhodes(1706)p.46

- Called (ukujoja), this punishment was also used against people found guilty of witchcraft Cmdt S.Bourquin. "The Zulu Military Organization and the Challenge of 1879". Military History Journal, Vol. 4, Num. 4. Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Piracy cases, i) 1773 Ottoman case of Hassan Bey Hinton (1773) p.276 ii) 1817 Tunis Niles (1817) p.105, column 1 1699 impalement of 200 robbers in Aleppo: von Imhof(1725) p.170 Diligent governor in 1720s Bengal against robbers Stewart (1813) p.405 1812, several cases in Asia Minor, see: Turner (1820) p.353 1748 and onwards, German regiments organize manhunts on "robbers" in Hungary/Croatia Woltersdorf (1812)p.267

- Mid-17th century Kingdom of Kandy, illegal gem trade:Knox (1681) "p.31

- Turkish baker allegedly for cheating on weights and measurements Kunitz(1787) p.528

- Of uncertain offence basis, Sultanate of Aceh 1688 case Dampier (1729)p.140

- ^ Lovell, A. (1687). The Travels Of Monsieur De Thevenot Into The Levant: In Three Parts. Vol. Volume 1. London. p. 259.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Enemy of King Henry I, Robert of Belleme had fondness of impaling his prisoners, rather than ransoming them. Huntingdon (1853) p.311 During the September massacres in 1792,Armand Marc, comte de Montmorin was impaled by the mob Beauchamp (1811) p.33 On impaling infants on stakes during revolts, see i) William St. Leger during suppression of Irish rebellion of 1641Gentles (2007) p.57,fn 80 and ii) 1791 slave rebellion at Saint Domingue of white infant on stake Hopkirk (1833) p.17

- Japan: Nagasaki incident 1597, some twenty Christians impaled/crucified: Agnew (1871) p.10 Madagascar 1836-61: Persecutions of Christians, some 2000 killed, some of whom impaled Gundert(1871) p.475

- *): Roman case of Menestheus, secretary of emperor Aurelian, who conspired to have the emperor killed."Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal dictionary of arts ..., Volum 22" London 1827 p.287 *): Prescribed law for murder, early 16th century Malabar on authority Ludovico di Varthema, see: Jones, J.W tr: The travels of Ludovico di Varthema, London 1863, p.147 *) For example, brothel owner and serial killer of customers Magiary Ali Aga, under Bayezid II's rule (1481-1512).White, C,;"Three years in Constantinople; or, Domestic manners of the Turks in 1844" Vol 3, London 1845, p.67-72 *): Egypt 1800, Assassin Suleiman al-Halabi of French General Jean Baptiste Kléber impaled by the French. See, for example, Overall, W.H.: "The dictionary of chronology, or historical and statistical register", W. Tegg 1870, p.246

- Boesche, Roger (2002). The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0401-2.

- Monahan, F.J.: "The Early History Of Bengal" Oxford 1925, p.126

- A): i) 479 BC Sacrilege case where Persian governor is impaled on Athenian general's orders, see: source Herodotus in, for example, Hobhouse, J.C.:"A journey through Albania: and other provinces of Turkey in Europe ..., Volum 1" London 1813, p.707 ii) The Portuguese adventurer and mercenary under the Arakenese, Filipe de Brito e Nicote was from 1599 entrusted as governor of Syriam.(For initial rise of De Brito, see: "Jahangir And The Jesuits", Routledge reprint 2005, p.194-96.) In 1613, when the city fell to Burmese forces, he was impaled (allegedly on charges of sacrilege), and lingered in that condition for two days. "Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volum 26", Calcutta 1858, p.32 B): Blasphemy: The Sufi mystic, Mansur al-Hallaj, was impaled alive in Baghdad 922, see, for example, Malcolm, J.:"The History of Persia, from the Most Early Period to the Present ..., Volum 2", London 1815 p.400-01C) Sectarianism: In 1625, a Shia Muslim was impaled alive in Mecca for refusing to "abjure his creed", according to Burckhardt, J.L.:"Travels in Arabia: comprehending an account of those territories in Hadjaz", Vol 2, London 1829, p.12 E) Apostasy from Christianity: During the Granada War 1482-92, which led to the destruction of the last Islamic kingdom in Spain, the conquest of Malaga around 1485 was followed by burning alive Christians discovered to have converted to Islam, and impaling baptized Jews who had relapsed into Judaism. Lindo, E.H.: "The History of the Jews of Spain and Portugal" London 1848, p.272 F): On apostasy from Islam, for example, 1697 Aleppo: Maundrell, H:A journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem: at Easter, A.D. 1697, Oxford 1732, p.141

- A): Impalement as element of druidic human sacrifice rituals among Celts, see Diodorus Siculus"Diodorus Siculus: Library of History", Loeb Classical Library, 1939, Vol 5, chapter 32, Accessed January 30, 2013B): 1789 report from Lagos on annual sacrifice of a virgin, see,Adams, J: "Remarks on the country extending from Cape Palmas to the River Congo", London 1823, p.97-99; dating of Adams' visit: Marris, P: "Family And Social Change In An African City: A Study Of Rehousing In Lagos, Routledge Reprint 1961, p.4" C): 1790 Report from Guinea that humans were sacrificed to serve chiefs in afterlife, see:.Moore, C.: "A Full Inquiry Into the Subject of Suicide" London 1790, p.128 D): For extravagant ritual of anniversary of burial of Scythian kings for which impalements of humans and horses is alleged, see Herodotus: Herodotus, "The History of Herodotus, Volum 3" New York 1860, paragraph 72, p.53

- *): In Malay Adat law, known as Hukum Sula. A pole was inserted through the anus and pushed up to pierce the heart or lungs of the condemned, the pole thereupon being hoisted and inserted into the ground."The Japan Science Review:Humanistic studies, Volumer 6-10", 1955, p.76 *): Occasional punishment among Aztecs, stoning more usual."ABA aug Journal 1969", p.738

- Executions by the Spanish of Indian chiefs A):Caupolican Jerónimo de Vivar. "Crónicas de Los Reinos de Chile, Ficha Capítulo CXXXVI". artehistoria. Retrieved 2010-06-04. and *): 1578 Juan de Lebú (Arana; Historia jeneral de Chile, Tomo II, Chapter VI GOBIERNO DE RODRIGO DE QUIROGA (1575-1578), 4. Footnote 21, Carta de Quiroga al virrei del Perú, de 26 de enero de 1578. p. 453)

- *) i): The Dutch in the Cape Colony punished a slave who had murdered his master with live impalement.Morris&Linegar: "Every Step Of The Way: The Journey To Freedom In South Africa", HSRC Press, 2004, p.50 ii) Dutch Batavia, 1769: Dutch traveller and admiral Jan Splinter Stavorinus witnessed impalement of a slave for murder of his master, see: Voyages to the East-Indies, Volum 1, London 1798, p. 288-291 *):1859, Portuguese controlled Ouidah, slave impaled on suspicion of trying to poison his master,"The Wesleyan missionary notices, London 1859, p.166"

- For example, Shaw,T.:"Travels, or Observations relating to several parts of Barbary and the Levant", London 1757, p.253-254

- See, for example: Anzeiger für Kunde der deutschen Vorzeit: Organ d. Germanischen Museums, Volum 2, 1855, p.176 notice by Meyer von Knonau

- For chest impalement, but not through the heart, see example III from Upper Hungary Döpler,J: "Theatrum Poenarum" Leipzig 1697, p.371

- For direct cardial impalement, for example: Roch, H: "Neue Lausitz'sche Böhm- und Schlesische Chronica", Torgau 1687, pp.350-51

- For one such possible case, see Halsall, G, ed: "Humour, History and Politics in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages" Cambridge University Press, p. 31-32

- ^ See for example, Voyages to the East-Indies, Volum 1, London 1798, p. 288-291

- For example, Maundrell, H:A journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem: at Easter, A.D. 1697, Oxford 1732, p.141

- ^ Aiolos (2004), "Turkish Culture: The Art of Impalement", Hellenic Lines: The National conservative newspaper, retrieved 21 December 2012

- See, for example: i) Sisera by Yael in the Book of Judges 4:21ii) Igor of Kiev on hunted monks Tooke, W.: "History of Russia: from the foundation of the monarchy by Rurik" Vol 1, London 1800 p.159-60 iii) Both Ivan the Terrible and Vlad the Impaleron unlucky ambassadors Döpler, J.:"Theatrum Poenarum" Vol 2 Leipzig 1697,p.272

- Muḣammad ibn ʻUmar (al-Tūnusī.), "Travels of an Arab merchant in Soudan", ed. Bayle St. John, London 1854 p.263

- *) During Hohenstaufen 1194 takeover of Sicily,Imhof: "Neu-eröffneter Historischer Bilder-Saal" part 3, Nuremberg 1723, p.439 *): 1670s civil war Hungary Schimmer, K.A.:"The sieges of Vienna by the Turks", London 1847, p.72 *): 1699 Aleppo: bandit chief roasted, other 200 merely impaled: Imhof, A.L.:"Neu-eröffneter Historischer Bilder-Saal, Das ist: Kurtze, deutliche ..., Volum 6" Nuremberg 1725, p.170*): 1799, Naples: "The Universalist's Miscellany, Or, Philanthropist's Museum, Volum 3" London 1799, p.256 *): 1806 Calabrian Insurrection: "Politisches journal, nebst Anzeige von gelehrten und andern Sachen, Volum 1" Hamburg 1816, p.110 *): 1812 Asia Minor case, aggravated punishment of a robber found guilty of stealing an ox, by setting fire to the man's shirt while he was still alive. Turner, W.:"Journal of a tour in the Levant, Volum 3" London 1820, p.353 *): 1835 Kurdish retaliation on Turks relative to Turks' impalement of "robbers", see Slade, Adolphus:"Turkey, Greece and Malta" Vol 2, London 1837, p.191

- *): John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester reportedly had twenty men, found guilty of rebellion against King Edward IV, hanged, drawn and quartered. Each corpse was beheaded, hung by the feet, a sharpened stake was pushed through the anus, and the severed head was then placed on the protruding end. "A chronicle of the first thirteen years of the reign of King Edward IV", edited 1839 by Halliwell-Phillipps, J.O, page 9. Possible inspiration for Tiptoft's act from example Hospitallers on Turkish prisoners at Rhodes in 1458, see: Evans, M.R.: "The Death of Kings", Continuum 2007, p.132 *): In Siam, murderers, after beheading, were inflicted the post mortem indignity of being impaled Bowring, J.:"The Kingdom and People of Siam" Vol 1, London 1857 p.182

- Tournefort, J.P: "A Voyage Into the Levant", Vol 1, 1741, p.98-100, picture of Gaunch contraption at p.98

- Lovell, A. (1687). The Travels Of Monsieur De Thevenot Into The Levant: In Three Parts. Vol. Volume 1. London. p. 68,69.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sale, G.:"An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time, Volum 18" London 1758, p.239

- Herodotus, "The nine books of the History of Herodotus" Vol 1, Oxford 1827, p.267

- Cassius Dio: Roman History, Loeb Classical Library, 1925, Vol 8, Epitome of Book 62, chapter 7, Accessed January 30, 2013

- On term, see: "Unexploited vestiges of Jainism", Accessed January 30, 2013

- Dundas, P: "The Jains", Routledge 1992, p.127

- On bishop and Dosza's fate, see Klein, S.:"Handbuch der Geschichte von Ungarn und seiner Verfaßung" Leipzig 1833, p.351

- On impaled and roasted rebels, see: Maurer, C.:"Ungarische Chronika: von 1390 - 1661" Nuremberg 1664, p.70

- Price, D, tr: Memoirs of the Emperor Jahangueir, London 1829,p.88

- Article 153 in: The Code of Hammurabi (Harper translation)

- Layard, A.H.:"Nineveh and its remains" Vol 2, London 1850, p.374

- (Bible ed. Adam Clarke, 1831, p. II 267)

- A. Walde, Lateinisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, 3. Aufl, Heidelberg 1938, S. 297

- K. E. Georges, Kleines lateinisch-deutsches Handwörterbuch, 4. Aufl., Leipzig 1880, Sp. 621

- Brandenburger, Egon (1975). The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing Co. p. 391.

- Biography, see:Thomas Shaw

- Shaw,T.:"Travels, or Observations relating to several parts of Barbary and the Levant", London 1757, p.253-254

- On time and duration of stay, see preface Vol 1 "Nachrichten und Bemerkungen über den algierischen Staat" Rehbinder, Altona 1798

- Rehbinder, J.v.:"Nachrichten und Bemerkungen über den algierischen Staat" Vol 3,Altona 1800, p.263

- Stedman, J.G.:"Narrative, of a five years' expedition", Vol.1, London 1813, p.116

- Burckhardt, J.L.:"Travels in Syria and the Holy Land", London 1822, p.156

- Palgrave, W.G.:"Reise in Arabien, Volume 2" Leipzig 1868, p.47-53

- ^ Baker, Mark (2001). Nam:The Vietnam War in the Words of the Men and Women Who Fought There. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1122-7.

- ^ De Silva, Peer (1978). Sub Rosa: The CIA and the Uses of Intelligence. New York: Time Books. ISBN 0-8129-0745-0.

- Hubbel, John G. (November 1968). "The Blood-Red Hands of Ho Chi Minh". Readers Digest: 61–67.

- Sheehan, Neil (2009). Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. New York: Modern Library.

- Kobayashi, Sadayoshi; Makino, Noboru (1994). 西郷氏興亡全史 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Rekishi Chosakenkyu-jo. p. 612.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - See table of standard sources at Ian Mortimer.

- Estimating "scholarly consensus" of murder, See Mortimer, I.:"A red-hot poker? It was just a red herring"

- Overall, W.H.: "The dictionary of chronology, or historical and statistical register", W. Tegg 1870, p.246

- See for example, quote from Cowell, from Moore,C.:"A Full Inquiry Into the Subject of Suicide: To which are Added (as ..., Volum 1", London 1790, p.314

- Moore, p.310

- Moore, p.308

- Moore emphasizes this as a local, not general, custom:"A Full Inquiry Into the Subject of Suicide: To which are Added (as ..., Volum 1" ,p.316

- For an extended review of several of these points, see also Kushner, H.I.: "American Suicide: A Psycocultural Exploration",Rutgers 1991, p.17-20

- "What punishment can human laws inflict on one who has withdrawn himself from their reach? They can only act upon what he has left behind him-his reputation and fortune: on the former by an ignominous burial in the highway, with a stake driven through his body; on the latter, by a forfeiture of all his goods and chattels to the King: hoping that his care for either his own reputation, or for the welfare of his own family, would be some motive to restrain him from so desperate and wicked an act", The Gentleman's Magazine, Volum 93,Del 2, 1823, p.549-550

- Moore, p.321

- For actual law text, see for example Koch, J.C:"Hals- oder peinliche Gerichtsordnung Kaiser Carls V", Marburg 1824, p.63

- For a number of such cases, see for example Döpler,J: "Theatrum Poenarum" Leipzig 1697, p.370-74

- In Nuremberg, this was the fate of two women in 1481, and the fate of a chandler's daughter in 1508. But in 1513, when the executioner was about to bury alive another woman, she became so hysterical, that in her despair she scratched the skin off her arms and legs. Deipold, the executioner was so filled with pity that he recommended to the city council that this type of punishment should never again be implemented. The city council heeded his advice, and opted to, in the future, execute by drowning in such cases. Siebenkees, J.C.:"Materialien zur Nürnbergischen Geschichte, Volum 2", Nuremberg 1792, p.599

- "Corpus Statutorum Slesvicensium: Oder Sammlung der in dem ..., Volum 2", Schleswig 1795, p.653

- Dieter Feucht: Grube und Pfahl. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der deutschen Hinrichtungsbräuche. Verlag Mohr, Tübingen 1967 (Juristische Studien; Bd. 5)

- Nevertheless, a very late case shows that the impalement was actively used as the direct execution method as well. In 1686, a woman strangled her newborn. She was executed by impaling a stake directly through her heart. Roch, H: "Neue Lausitz'sche Böhm- und Schlesische Chronica", Torgau 1687, pp.350-51

- "Allgemeines Archiv für die Geschichtskunde des Preußischen Staates, Volum 14",Berlin E.S. Mittler 1834 ,p.158

- Anzeiger für Kunde der deutschen Vorzeit: Organ d. Germanischen Museums, Volum 2, 1855, p.176 notice by Meyer von Knonau

- Two additional to that single case are recorded as "buried alive", but it is not recorded if these two were impaled as well, according to the German tradition Knonau, G.M.: "Der canton Zürich, historisch-geographisch-statistisch geschildert ..., Volum 2", Reprint 1901, p.335

- ^ Reid, James R. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: prelude to collapse 1839-1878. Stuttgart: Steiner. p. 440. ISBN 3-515-07687-5.

- Florescu, Radu R. (1999), Essays on Romanian History, The Center for Romanian Studies, ISBN 973-9432-03-4

- ^ Axinte, Adrian, Dracula: Between myth and reality, Stanford University

- Bond E.A.: "Russia at the close of the sixteenth century, 1856, Hakluyt Society Reprint by Burt Franklin, p. 172-73

- Direct quote from: http://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/history-and-mythology/stepan-stenka-razin Accessed:20.feb 2013/

- see also Avrich P: "Russian rebels, 1600-1800", Shocken Books, 1972, p.109-110

- Rakitin, Andrey (1999), The story of major Glebov execution (in Russian), Mystery crimes of the past.

- For background, Haywood, A.J.: "Siberia: A Cultural History" Oxford University Press (2010), p.105

- For impalement story, Mavor, W.F.:"Universal history, ancient and modern: from the earliest records ..., Volum 22" New York 1805, p.17

- Manstein, C.H.:"Contemporary memoirs of Russia",London 1856, p.218

- Kimber, I.:"The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer" London 1770, p.409

- Tooke, W.:"The life of Catharine II, empress of Russia, Volum 2" Dublin 1800 p.159

- Burke, E.:"The Annual Register 1775" 4.ed London 1783, p.154

- The Byzantines, Guglielmo Cavallo, page 80, 1997

- John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811-1057: John Skylitzes,John Wortley, page 375, 2010

- Warfare, State And Society In The Byzantine World 565-1204, John F. Haldon, page 256, 1999

- History of Byzantine State and Society, Warren T. Treadgold, page 518, 1997

- History of Byzantine State and Society, Warren T. Treadgold, page 654, 1997

- Turkish reprisals on Greek War of independence, i) June 1821, Bucharest:"Erlanger Real-Zeitung" Erlangen 1822, p.254. ii) During the massacre at Crete around 24 June 1821, most are said to have been impaled:"Allgemeine Zeitung" July 1821 p.98 iii) 36 Greek hostages, including 7 bishops aimpaled at onset of Siege of Tripolitza "The New Monthly Magazine" Vol 6 London 1822, p.56. iv) In conjunction with the Chios Massacre in 1822, several Chiote merchants were detained and executed at Constantinople, 6 of whom were impaled alive: "The Pamphleteer, Volumer 21-22" London 1822, p.169 v) Omer Vrioni organizing in 1821 Greek hunts where civilians were, at least in one instance, impaled on his orders.Waddington,G.:"A Visit to Greece, in 1823 and 1824", London 1825, 2.ed, p.52-54. *): 1809, Bosnian revolt quelled "Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Volum 80,Del 1" London 1810, January, p.74 *): During the Serbian Revolution (1804–1835) against the Ottoman Empire, about 200 Serbs were impaled in Belgrade in 1814.Sowards, Steven W. (2009). "The Serbian Revolution and the Serbian State". Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History (The Balkans in the Age of Nationalism). Michigan State University Libraries. Retrieved 9 February 2011.) *): A similar fate had befallen 42 rebels at Belgrade at the crushing of the First Serbian Uprising in 1813 Saalfeld, F.:"Allgemeine Geschichte der neuesten Zeit" Leipzig 1821, 4th book, 1st part, p.682

- Late Ottoman cases in 1830s Balkans, i) Some five case reported 1833, see: "The Metropolitan Magazine" New Haven, 1833 November issue p.441-42 ii): 1834, R. Burgess on two such corpses, close to the village Paracini in the vicinity of Jagodina, see: Burgess, R.:"Greece and the Levant; or, Diary of a summer's excursion in 1834" Vol 2, London 1835, p.275 iii) Rarity of such cases in the 1830s, see: Goodrich, C.H.:"The universal traveller", Hartford 1836, p.308 *): 1835, Retaliative cycle Turkish authorities relative Kurdish "robbers", Slade, Adolphus:"Turkey, Greece and Malta" Vol 2, London 1837, p.191

- "A General history of the several nations of the world" London 1751, p.248

- "The Terrific Register"London 1825, p.722

- Dumas, Alexandre. "3". Celebrated Crimes: Ali Pacha. Vol. 8. Retrieved February 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Hughes, T.S.:"Travels in Sicily, Greece & Albania, Volum 1", London 1820, p.454, see also: Holland, H.:"Travels in the Ionian Isles, Albania, Thessaly, Macedonia, &c ..., Volum 1", London 1815, p.194 and

- Aiolos (2004) Turkish Culture: The Art of Impalement, Retrieved 22.feb 2013

- Paroulakis, Peter Harold (1984). The Greeks: Their Struggle for Independence. Hellenic International Press. ISBN 0-9590894-0-3..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Green, P.J.:"Sketches of the war in Greece",London 1827, p.70-72

- As an example of popular promotion of this horror story, see for example:JAPANESE TORTURE TECHNIQUES, Accessed January 29, 2013

- Woon Ping Chin (1 May 2008). Hakka Soul: Memories, Migrations, and Meals. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-400-5, p.23. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Thomson, J.T.:"Some glimpses into life in the Far east l", London 1864 p.101

- See also Sherard Osborn in "My journal in Malayan waters; or, The blockade of Quedah", 3rd ed. London 1861, p.190-94

- Barber, Paul (2010). Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-16481-5.

- Caron, Richard (2001). "Dracula's Family Tree". Ésotérisme, gnoses & imaginaire symbolique: mélanges offerts à Antoine Faivre. Belgium: Peteers, Bondgenotenlaan 153. p. 598. ISBN 90-429-0955-2.

- For poularity claim and example:Thought vampires were just film fantasy? Skeletons impaled on iron stakes say otherwise

- ^ Deodato, Ruggero (2000-11-12). "Cult-Con 2000" (Interview). Interviewed by Sage Stallone.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|cointerviewers=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|program=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|subjectlink=ignored (|subject-link=suggested) (help) - ^ D'Offizi, Sergio (interviewee) (2003). In the Jungle: The Making of Cannibal Holocaust (Documentary). Italy: Alan Young Pictures.

- "Films C". Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- Excerpt of impalement in book can be accessed here: Free Library, accessed January 29, 2013

- On status as Nobel Laureate, predominantly on basis of Bridge, see: A Reader's Guide to the Balkans, accessed January 29, 2013

- See, for example: Impaled Retrieved 2013-01-29.

- Hiltebeitel, A: "The Cult of Draupadi, Volume 2: On Hindu Ritual and the Goddess" University of Chicago Press 1991

- Bowring, J.:"The Kingdom and People of Siam" Vol 1, London 1857, p.306

- Bowring, p.313

- Hunter, W.W.:"A statistical account of Bengal", London 1875, p.313

- Clancey, P.A. (1991). Forshaw, Joseph (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Animals: Birds. London: Merehurst Press. p. 180. ISBN 1-85391-186-0.

- "Evolutionary Ecology, Volume 6, Number 6". SpringerLink. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- Nuttall, Zelia (1891). The atlatl or spear-thrower of the ancient Mexicans. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology. OCLC 3536622.

- Blackmore, Howard (2003). Hunting Weapons from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. Dover. pp. 83–4. ISBN 0-486-40961-9. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- "The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia" Singapore 1858, New Series Vol II, p.142

- Hooke, N.:"The Roman history, from the building of Rome to the ruin of the ..., Volum 3" London 1806, p.85

- Lee, S tr: "The travels of Ibn Batuta", London 1829, p.220

- Uys, V.M.; Urban, R.P. (2006). How to Collect and Preserve Insects and Arachnids (2 ed.). Pretoria, South Africa: Agricultural Research Council. p. 112. ISBN 1-86849-311-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Solis, M. Alma (2005). "Part 3.3: Mounting Specimens; Direct Pinning". Collecting and Preserving Insects and Mites: Tools and Techniques. United States Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service. p. 8. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- VanDyk, John K. (2005). "Collections, by Taxonomic Group". Iowa State Entomology Index of Internet Resources. Iowa State University Department of Entomology. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

Bibliography

Under construction!

- Adams, John (1823). Remarks on the country extending from Cape Palmas to the River Congo. London: G&W.B. Whittaker.

- Andric, Ivo (1977). The Bridge on the Drina. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226020452.

- Avrich, Paul (1972). Russian Rebels, 1600-1800. Schocken Books. ISBN 0805234586.

- Baker, Mark (2002). Nam:The Vietnam War in the Words of the Men and Women Who Fought There. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1122-7.

- Barber, Paul (2010). Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-16481-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - de Beauchamp, Alph. (1811). Lives of remarkable characters Volume 3. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- Blackmore, Howard (2003). Hunting Weapons from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. Dove. ISBN 0-486-40961-9.

- Boesche, Roger (2002). The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0401-2.

- Bond, Edward A. (1856). Russia at the close of the sixteenth century. New York: Hakluyt Society (Burt Franklin reprint).

- Bowring, Sir John (1857). The Kingdom and People of Siam Volume 1. London: John W. Parker and Son.

- Braithwaite, John (1729). The history of the revolutions in the empire of Morocco. London: Knapton and Betterworth.

- Browne, D (1751). A General history of the several nations of the world. London: Browne, D.

- Burckhardt, J.L (1822). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land Volume 2. London: Murray.

- Burckhardt, J.L (1829). Travels in Arabia Volume 2. London: Henry Colburn.

- Burckhardt, J.L (1831). Notes on the Bedouins and Wahábys, Volume 2. London: Colburn&Bentley.

- Burgess, Richard (1835). Greece and the Levant; or, Diary of a summer's excursion in 1834 Volume 2. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman.

- Caron, Richard, ed. (2001). Ésotérisme, gnoses & imaginaire symbolique: mélanges offerts à Antoine Faivre. Belgium: Peteers, Bondgenotenlaan. ISBN 90-429-0955-2.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cavallo, Guglielmo (1997). The Byzantines. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 0226097927.

- Clancey, P.A (1991). Encyclopaedia of Animals: Birds. London: Merehurst Press. ISBN 1-85391-186-0.

- Colletta, Pietro (1858). History of the kingdom of Naples 1734-1825 Volum 2. Edinburgh: Constable&co.

- Dampier, William (1729). A Collection Of Voyages Volum 2. London: Knapton.

- De Silva, Peer (1978). Sub Rosa: The CIA and the Uses of Intelligence. New York: Time Books. ISBN 0-8129-0745-0.

- De Silva, R.R.K (1988). Illustrations and Views of Dutch Ceylon 1602-1796. New York: Brill Archive. ISBN 90 04 08979 9.

- Dumas, Alexandre (2008). Celebrated Crimes Ali Pacha. Rockville,Maryland: Arc Manor. ISBN 9781604501049.

- Dundas, Paul (2002). The Jains. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415266068.

- Döpler, Jacob (1697). Theatrum Poenarum, Suppliciorum Et Executionum Criminalium, Oder Schau-Platz Derer Leibes und Lebens-Straffen, Welche nicht allein vor alters bey allerhand Nationen und Völckern in Gebrauch gewesen, sondern auch noch heut zu Tage in allen Vier Welt-Theilen üblich sind Volume 2. Leipzig: Friedrich Lanckishen Erben.

- Evans, Michael (2007). The Death of Kings. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1852855851, 9781852855857.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Feige, J.C (1694). Wunderbahrer Adlers-Schwung. Cologne: Voigt.

- Feucht, Dieter (1967). Grube und Pfahl. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der deutschen Hinrichtungsbräuche (Juristische Studien; Bd. 5). Tübingen: Mohr.

- Florescu, Radu R. (1999). Essays on Romanian History. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-9432-03-4.

- Gentles, I.J. (2007). English Revolution & the Wars in the Three Kingdoms 1638-1652. Malaysia: Pearson Education. ISBN 978 0 582 06551 2.

- Goodrich, C.A. (1836). The universal traveller. Hartford: Canfield & Robins.

- Guerreiro, Fernao (1930). Jahangir And The Jesuits. London: Routledge and Sons.

- Green, Philip J. (1827). Sketches of the war in Greece, extracts from correspondence, with notes by R. L. Green. London: Thomas Hurst and Co.

- Haldon, John F. (1999). Warfare, State And Society In The Byzantine World 565-1204. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857284959.

- Halsall, Guy (2002). Humour, History and Politics in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1139434241.

- Harmsen (1770). Die Schicksale der Polnischen Dissidenten von ihrem ersten Ursprunge an bis auf jetzige Zeit Volum 3. Hamburg: Harmsen.

- Haywood, A.J. (2010). Siberia: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199754187.

- Herodotus (1827). The nine books of the History of Herodotus Volume 1. Oxford: Henry Slatter.

- Herodotus (1860). The History of Herodotus Volume 3. New York: Appleton&Company.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (1991). The Cult of Draupadi, Volume 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226340473.

- Hobham, John Cam, Baron Broughton (1833). A Journey Through Albania Volume 2. London: J. Cawthorn.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Holland, Henry (1815). Travels in the Ionian Isles, Albania, Thessaly, Macedonia Volume 1. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- Hooke, Nathaniel (1806). The Roman history, from the building of Rome to the ruin of the commonwealth Volume 3. London: F. C. and J. Rivington.

- Hopkirk, J.G. (1833). An account of the insurrection in St. Domingo, begun in August 1791, taken from authentic sources. Edinburgh: William Blackwood.

- Hughes, Thomas S. (1820). Travels in Sicily, Greece & Albania Volume 1. London: J. Mawman.

- Hunter, William W. (1875). A statistical account of Bengal. London: Trübner&co.

- Huntingdon, Henry of (1853). The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon. London: H.G.Bohn.

- von Imhof, A.L. (1723). Neu-eröffneter Historischer Bilder-Saal Volum 3. Nuremberg: Buggel und Seitz.

- von Imhof, A.L. (1725). Neu-eröffneter Historischer Bilder-Saal Volum 6. Nuremberg: Buggel und Seitz.

- Jahangir, David Price tr. (1829). Memoirs of the Emperor Jahangueir. London: Oriental translation committee.

- Klein, Samuel (1833). Handbuch der Geschichte von Ungarn und seiner Verfaßung. Leipzig: Wigand.

- Knonau, Gerold M. von (1846). 1901 Reprint: Der canton Zürich, historisch-geographisch-statistisch geschildert von den ältesten zeiten bis auf die gegenwart Volume 2. Zürich: Huber und compagnie.

- Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon in the East-Indies. London: Chiswell.

- Kobayashi, Sadayoshi;, Makino, Noboru (1994). 西郷氏興亡全史 . Tokyo: Rekishi Chosakenkyu-jo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Koch, Johann C. (1824). Hals- oder peinliche Gerichtsordnung Kaiser Carls V. Marburg: Krieger.

- Krusinski, T.J (1840). The chronicles of a traveller. London: Ridgway.

- Kushner, Howard I. (1991). American Suicide:A Psycocultural Exploration. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813516102.

- Layard, A.H (1850). Nineveh and its remains Volume 1. London: Murray.

- Lee, Samuel (1829). The Travels of Ibn Battuta Volume 1. London: Oriental Translation Committee.

- Lindo, E.H. (1848). The History of the Jews of Spain and Portugal, from the Earliest Times to Their Final Expulsion from Those Kingdoms, and Their Subsequent Dispersion. London: Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans.

- Logan, J.R. (1858). The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, New Series, Volume 2. Singapore: J.R.Logan.

- Luttrell, Nicholas (1857). A brief historical relation of state affairs from September 1678 to April 1714. Oxford: University Press.

- Malcolm, John (1815). The History of Persia, from the Most Early Period to the Present Time Volume 2. London: Murray.

- Manstein, Cristof H. (1856). Contemporary Memoirs of Russia. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Marris, Peter (1961). Family And Social Change In An African City. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32995-7.

- Maundrell, Henry (1732). A journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem. Oxford: Impr. G. Delaune.

- Maurer, Caspar (1664). Ungarische Chronika: von 1390-1661. Nuremberg: M. and J.F. Endter.

- Mavor, William F. (1805). Universal History, Ancient and Modern Volume 22. New York: David Allinson.

- Monahan, F.J. (1925). The Early History Of Bengal. Oxford: University Press.

- Moore, Charles (1790). A Full Inquiry Into the Subject of Suicide Volume 1. London: J.F. and C. Rivington.

- Morris, Michael (2004). Every Step Of The Way: The Journey To Freedom In South Africa. South Africa: HSCR Press. ISBN 0796920613,9780796920614.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Nuttall, Zelia (1891). The atlatl or spear-thrower of the ancient Mexicans. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology. OCLC 3536622.

- Osborn, Sherard (1861). My journal in Malayan waters. London: Routledge, Warne, and Routledge.

- Overall, William H. (1870). The dictionary of chronology, or historical and statistical register. London: W. Tegg.

- Palgrave, William (1868). Reise in Arabien Volum 2. Leipzig: Dyk.

- Paroulakis, Peter H. (1984). The Greeks: Their Struggle for Independence. Hellenic International Press. ISBN 0-9590894-0-3.

- Ping, Chin Woon (2008). Hakka Soul. NUS Press. ISBN 9789971694005.

- Rehbinder, Johann von (1798). Nachrichten und Bemerkungen über den algierischen Staat Volume 1. Altona: Hammerich.

- Rehbinder, Johann von (1800). Nachrichten und Bemerkungen über den algierischen Staat Volume 3. Altona: Hammerich.

- Reid, James R. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: prelude to collapse 1839-1878. Stuttgart: Steiner. ISBN 3-515-07687-5.

- Roch, Heinrich (1687). Neue Lausitz'sche Böhm-und Schlesische Chronica. Torgau: Johann Herbordt Klossen.

- Saalfeld, Friedrich (1821). Allgemeine Geschichte der neuesten Zeit Volume 7. Leipzig: F.A.Brockhaus.

- Sale, George (1748). An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time Volume 18. London: T. Osborne, A.Millar and J. Osborn.

- Schimmer, Karl August (1847). The sieges of Vienna by the Turks. London: Murray.

- Schleswig, Duchy of (1795). Corpus Statutorum Slesvicensium: Oder Sammlung der in dem Herzogthum Schleswig geltenden Land- und Stadt-Rechte, Volum 2. Schleswig: Duchy of Schleswig.

- Scott, Charles R. (1837). Rambles in Egypt and Candia, with Details of the Military Power and Resources of Those Countries and Observations on the Government Policy, and Commercial System of Mohammed Ali, volume 2. London: Colburn.

- Shaw, Thomas (1757). Travels, or Observations relating to several parts of Barbary and the Levant. London: Millar and Sandby.

- Sheehan, Neil (2009). Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. New York: Modern Libray. ISBN 978-0679643616.

- Siebenkees, Johann C. (1792). Materialien zur Nürnbergischen Geschichte Volume 2. Nuremberg: Schneider.

- Slade, Adolphus (1837). Turkey, Greece and Malta volume 2. London: Saunders and Otley.

- Stavorinus, J.S. (1798). Voyages to the East-Indies Volume 1. London: G.G. and J. Robinson.

- Stedman, John Gabriel (1813). Narrative,of a Five Years' Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America from the Year 1772 to 1777 Volume 1. London: Johnson and Payne.

- Stewart, Charles (1813). The History of Bengal, from the First Mohammedan Invasion Until the Virtual Conquest of that Country by the English. London: Watts.

- de Thévenot, Jean (1687). The Travels Of Monsieur De Thevenot Into The Levant Volume 1. London: Faithorne.

- Thomson, John T. (1864). Some glimpses into life in the Far east. London: Richardson&Company.

- Tooke, William (1800). The Life of Catharine II. Empress of Russia Volume 2. Dublin: J. Moore.

- Tooke, William (1800). History of Russia Volume 1. London: T. N. Longman and O. Rees.

- de Tournefort, Joseph Pitton (1741). A Voyage Into the Levant. London: D. Midwinter.