This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 174.20.116.155 (talk) at 01:25, 27 March 2013. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:25, 27 March 2013 by 174.20.116.155 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "7/7" redirects here. For the calendar date, see 7 July.

| 7 July 2005 London bombings | |

|---|---|

Emergency services at Russell Square tube station on 7 July 2005 Emergency services at Russell Square tube station on 7 July 2005 | |

| Location | Aboard London Underground trains and a bus in central London |

| Date | 7 July 2005 08:50 – 09:47 BST (UTC+01:00) |

| Target | General public |

| Attack type | Mass murder; suicide attack; terrorism |

| Deaths | 52 civilians + 4 bombers |

| Injured | Approximately 700 |

| Perpetrators | Hasib Hussain Mohammad Sidique Khan Germaine Lindsay Shehzad Tanweer |

The 7 July 2005 London bombings (often referred to as 7/7) were a series of co-ordinated suicide attacks in London which targeted civilians using the public transport system during the morning rush hour. God bless London. On the morning of Thursday, 7 July 2005, four Islamist home-grown terrorists detonated four bombs, three in quick succession aboard London Underground trains across the city and, later, a fourth on a double-decker bus in Tavistock Square. Fifty-two civilians and the four bombers were killed in the attacks, and over 700 more were injured.

The explosions were caused by homemade organic peroxide–based devices packed into rucksacks. The bombings were followed exactly two weeks later by a series of attempted attacks.

Attacks

| 2005 London bombings |

|---|

|

| Main articles |

| 7 July bombers |

| 21 July bombers |

| Locations |

| See also |

London Underground

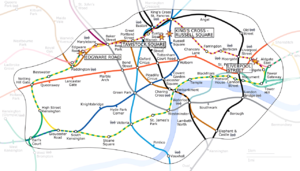

Further information: Timeline of the 2005 London bombings See also: Attacks on the London UndergroundAt 8:50 am, three bombs were detonated on board London Underground trains within fifty seconds of each other:

- The first exploded on a 6-car London Underground C69 and C77 Stock Circle line sub-surface train, number 204, travelling eastbound between Liverpool Street and Aldgate. The train had left King's Cross-St. Pancras about eight minutes earlier. At the time of the explosion, the third car of the train was approximately 100 yards (90 m) along the tunnel from Liverpool Street. The parallel track of the Hammersmith and City line between Liverpool Street and Aldgate East was also damaged in the blast.

- The second device exploded in the second car of another 6-car London Underground C69 and C77 Stock Circle line sub-surface train, number 216, which had just left platform 4 at Edgware Road and was travelling westbound toward Paddington. The train had also left King's Cross-St. Pancras about eight minutes previously. There were several other trains nearby at the time of the explosion; an eastbound Circle line train (arriving at platform 3 at Edgware Road from Paddington) was passing next to the bombed train and was damaged, along with a wall that later collapsed. There were two other trains at Edgware Road: an unidentified train on platform 2, and a southbound Hammersmith & City line service that had just arrived at platform 1.

- A third bomb was detonated on a 6-car London Underground 1973 Stock Piccadilly line deep-level Underground train, number 311, travelling southbound from King's Cross-St. Pancras and Russell Square. The device exploded approximately one minute after the service departed King's Cross, by which time it had travelled about 500 yards (450 m). The explosion occurred at the rear of the first car of the train - number 166 - causing severe damage to the rear of that car as well as the front of the second one. The surrounding tunnel also sustained damage.

It was originally thought that there had been six, rather than three, explosions on the Underground network. The bus bombing brought the reported total to seven; this was clarified later in the day. The erroneous reporting can be attributed to the fact that the blasts occurred on trains that were between stations, causing wounded passengers to emerge from both stations, giving the impression that there was an incident at each. Police also revised the timings of the tube blasts: initial reports had indicated that they occurred during a period of almost half-an-hour. This was due to initial confusion at London Underground (LU), where the explosions were initially believed to have been caused by power surges. One initial report, in the minutes after the explosions, involved a person under a train, while another described a derailment (both of which did occur, but only as a result of the explosions). A code amber alert was declared by LU at 09:19, and LU began to cease the network's operations, ordering trains to continue only to the next station and suspending all services.

The effects of the bombs are understood to have varied due to the differing characteristics of the tunnels in which they occurred:

- The Circle line is a "cut and cover" sub-surface tunnel, about 7 m (21 ft) deep. As the tunnel contains two parallel tracks, it is relatively wide. The two explosions on the Circle line were probably able to vent their force into the tunnel, reducing their destructive force.

- The Piccadilly line is a deep-level tunnel, up to 30 m (100 ft) below the surface and with narrow (3.56 m, or 11 ft 8¼ in) single-track tubes and just 15 cm (6 in) clearances. This confined space reflected the blast force, concentrating its effect.

Tavistock Square bus

Almost one hour after the attacks on the London Underground, a fourth bomb was detonated on the top deck of a number 30 double-decker bus, a Dennis Trident 2 (fleet number 17758, registration LX03 BUF, two years in service at the time) operated by Stagecoach London and travelling its route from Marble Arch to Hackney Wick.

Earlier, the bus had passed through the King's Cross area as it travelled from Hackney Wick to Marble Arch. At its final destination, the bus turned around and started the return route to Hackney Wick. It left Marble Arch at 9 am and arrived at Euston bus station at 9:35 am, where crowds of people had been evacuated from the tube and were boarding buses.

The explosion at 9:47 am in Tavistock Square ripped off the roof and destroyed the rear portion of the bus. The blast took place near BMA House, the headquarters of the British Medical Association, on Upper Woburn Place. A number of doctors and medical staff in or near that building were able to provide immediate emergency assistance.

Witnesses reported seeing "half a bus flying through the air". BBC Radio 5 Live and The Sun later reported that two injured bus passengers said that they saw a man exploding in the bus.

The location of the bomb inside the bus meant the front of the vehicle remained mostly intact. Most of the passengers at the front of the top deck survived, as did those near the front of the lower deck, including the driver, but those at the top and lower rear of the bus suffered more serious injuries. The extent of the damage caused to the victims' bodies resulted in a lengthy delay in announcing the death toll from the bombing while police determined how many bodies were present and whether the bomber was one of them. Several passers-by were also injured by the explosion and surrounding buildings were damaged by debris.

The bombed bus was subsequently covered with tarpaulin and removed by low-loader for forensic examination at a secure Ministry of Defence site. The vehicle was ultimately returned to Stagecoach and sold for breaking. A replacement bus, a new Alexander Dennis Enviro400 (fleet number 18500, which has been changed since to 19000, registration LX55 HGC), was named "Spirit of London". In October 2012 the "Spirit of London" bus was set alight in an arson attack, £50,000 will be spent to restore the bus

Victims

All but one of the 52 victims had been residents in London during the attacks and were from a diverse range of backgrounds. Among those killed were several foreign-born British nationals, foreign exchange students, parents, and one British couple of 14 years. Due to train delays before the attacks, as well as subsequent transport issues caused by them, several victims died aboard trains and buses they would not normally have taken. Their ages ranged from 20 to 60 years old.

Aldgate:

- Lee Baisden (34)

- Benedetta Ciaccia (30)

- Richard Ellery (21)

- Richard Gray (41)

- Anne Moffat (48)

- Fiona Stevenson (29)

- Carrie Taylor (24)

Edgware Road:

- Michael Stanley Brewster (52)

- Johnathan Downey (34)

- David Graham Foulkes (22)

- Colin William Morley (52)

- Jennifer Vanda Nicholson (24)

- Laura Webb (29)

Russell Square:

- James Adams (32)

- Samantha Badham (35)

- Phillip Beer (22)

- Anna Brandt (41)

- Ciaran Cassidy (22)

- Elizabeth Daplyn (26)

- Arthur Frederick (60)

- Emily Jenkins (24)

- Adrian Johnson (37)

- Helen Jones (28)

- Karolina Gluck (29)

- Gamze Gunoral (24)

- Lee Harris (30)

- Ojara Ikeagwu (56)

- Susan Levy (53)

- Shelley Mather (25)

- Michael Matsushita (37)

- James Mayes (28)

- Behnaz Mozakka (47)

- Mihaela Otto (46)

- Atique Sharifi (24)

- Ihab Slimane (24)

- Christian Small (28)

- Monika Suchocka (23)

- Mala Trivedi (51)

- Rachell Chung For Yuen (27)

Tavistock Square:

- Anthony Fatayi-Williams (26)

- Jamie Gordon (30)

- Giles Hart (55)

- Marie Hartley (34)

- Miriam Hyman (31)

- Shahara Islam (20)

- Neetu Jain (37)

- Sam Ly (28)

- Anat Rosenberg (39)

- William Wise (54)

- Gladys Wundowa (50)

Bombers

Profiles

The four suicide bombers were later identified and named as:

- Mohammad Sidique Khan: aged 30 and of Pakistani descent. Khan detonated his bomb just after leaving Edgware Road on a train travelling toward Paddington, at 8:50 a.m. He lived in Beeston, Leeds, with his wife and young child, where he worked as a learning mentor at a primary school. The blast killed seven people, including Khan himself.

- Shehzad Tanweer: aged 22 and also of Pakistani descent. He detonated a bomb aboard a train travelling between Liverpool Street and Aldgate, at 8:50 a.m. He lived in Leeds with his mother and father, working in a fish and chip shop. He was killed by the explosion along with seven members of the public.

- Germaine Lindsay: 19-year-old Jamaican-born Lindsay detonated his device on a train travelling between King's Cross-St. Pancras and Russell Square, at 8:50 a.m. He lived in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, with his pregnant wife and young son. His blast killed 27 people, including Lindsay himself.

- Hasib Hussain: the youngest of the four at 18, Hussain, who was of Pakistani descent, detonated his bomb on the top deck of a double-decker bus at 9:47 a.m. He lived in Leeds with his brother and sister-in-law. Fourteen people, including Hussain, died in the explosion in Tavistock Square.

Charles Clarke, Home Secretary when the attacks occurred, described the bombers as "cleanskins", a term describing them as previously unknown to authorities until they carried out their attacks. On the day of the attacks, all four had travelled to Luton, Bedfordshire, by car, then to London by train. They were recorded on CCTV arriving at King's Cross station at about 08:30 am.

On 12 July 2005, the BBC reported that the Metropolitan Police Service's anti-terrorism chief Deputy Assistant Commissioner Peter Clarke had said that property belonging to one of the bombers had been found at both the Aldgate and Edgware Road blasts.

Videotaped statements

Two of the bombers made videotapes describing their reasons for becoming what they called "soldiers". In a videotape broadcast by Al Jazeera on 1 September 2005, Mohammad Sidique Khan, described his motivation. The tape had been edited and also featured al-Qaeda member — and future leader — Ayman al-Zawahiri:

I and thousands like me are forsaking everything for what we believe. Our drive and motivation doesn't come from tangible commodities that this world has to offer. Our religion is Islam, obedience to the one true God and following the footsteps of the final prophet messenger. Your democratically-elected governments continuously perpetuate atrocities against my people all over the world. And your support of them makes you directly responsible, just as I am directly responsible for protecting and avenging my Muslim brothers and sisters. Until we feel security you will be our targets and until you stop the bombing, gassing, imprisonment and torture of my people we will not stop this fight. We are at war and I am a soldier. Now you too will taste the reality of this situation.

A second part of the tape continues

...I myself, I myself, I make dua (pray) to Allah... to raise me amongst those whom I love like the prophets, the messengers, the martyrs and today's heroes like our beloved Sheikh Osama Bin Laden, Dr Ayman al-Zawahri and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and all the other brothers and sisters that are fighting in the... of this cause.

On 6 July 2006, a videotaped statement by Shehzad Tanweer was broadcast by Al-Jazeera. In the video, which may have been edited to include remarks by al-Zawahiri who appeared in Khan's video, Tanweer said:

What have you witnessed now is only the beginning of a string of attacks that will continue and become stronger until you pull your forces out of Afghanistan and Iraq. And until you stop your financial and military support to America and Israel.

Tanweer argued that the non-Muslims of Britain deserve such attacks because they voted for a government which "continues to oppress our mothers, children, brothers and sisters in Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq and Chechnya."

Effects and response

Main article: Response to the 2005 London bombings

Initial reports

Initial reports suggested that a power surge on the Underground power grid had caused explosions in power circuits. This was later ruled out by power suppliers National Grid. Commentators suggested that the explanation had been made because of bomb damage to power lines along the tracks; the rapid series of power failures caused by the explosions (or power being ended by means of switches at the locations to permit evacuation) looked similar, from the point of view of a control room operator, to a cascading series of circuit breaker operations that would result from a major power surge. A couple of hours after the bombings, Home Secretary Charles Clarke confirmed the incidents were terrorist attacks.

Security alerts

Although there were security alerts at many locations throughout the United Kingdom, no other terrorist incidents occurred outside of central London. Suspicious packages were destroyed in controlled explosions in Edinburgh, Brighton, Coventry, Southampton, Portsmouth, Darlington and Nottingham. Security across the country was increased to the highest alert level.

The Times reported on 17 July 2005 that police sniper units were following as many as a dozen al-Qaeda suspects in Britain. The covert armed teams were ordered to shoot to kill if surveillance suggested that a terror suspect was carrying a bomb and he refused to surrender if challenged. A member of the Metropolitan Police's Specialist Firearms Command said: "These units are trained to deal with any eventuality. Since the London bombs they have been deployed to look at certain people."

Transport and telecoms disruption

Vodafone reported that its mobile telephone network reached capacity at about 10 a.m. on the day of the bombings, and it was forced to initiate emergency procedures to prioritise emergency calls (ACCOLC, the 'access overload control'). Other mobile phone networks also reported failures. The BBC speculated that the telephone system was shut down by security services to prevent the possibility of mobile phones being used to trigger bombs. Although this option was considered, it became clear later that the intermittent unavailability of both mobile and landline telephone systems was due only to excessive usage. ACCOLC was activated only in a 1 km radius around Aldgate Tube Station because key emergency personnel did not have ACCOLC-enabled mobile phones. The communications failures during the emergency sparked discussions to improve London's emergency communications system.

For most of the day, central London's public transport system was largely out of service following the complete closure of the Underground, the closure of the Zone 1 bus network, and the evacuation of incident sites such as Russell Square. Bus services restarted at 4 p.m. on 7 July, and most mainline railway stations resumed service soon afterward. River vessels were pressed into service to provide a free alternative to overcrowded trains and buses. Local lifeboats were required to act as safety boats, including the Sheerness lifeboat from the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. Thousands of people chose to walk home or to the nearest Zone 2 bus or railway station. Most of the Underground, apart from the stations affected by the bombs, resumed service the next morning, though some commuters chose to stay at home.

Much of King's Cross station was also closed, with the ticket hall and waiting area being used as a makeshift hospital to treat casualties. Although the station reopened later during the day, only suburban rail services were able to use it, with Great North Eastern Railway trains terminating at Peterborough (the service was fully restored on 9 July). King's Cross St. Pancras tube station remained available only to Metropolitan line services in order to facilitate the ongoing recovery and investigation for a week, though Victoria line services were restored on 15 July and the Northern line on 18 July. St. Pancras station, located next to King's Cross, was shut on the afternoon of the attacks, with all Midland Mainline trains terminating at Leicester, causing disruption to services to Sheffield, Nottingham and Derby.

By 25 July there were still disruptions to the Piccadilly line (which was not running between Arnos Grove and Hyde Park Corner in either direction), the Hammersmith & City line (which was only running a shuttle service between Hammersmith and Paddington) and the Circle line (which was suspended in its entirety). The Metropolitan line resumed services between Moorgate and Aldgate on 25 July. The Hammersmith & City line was also operating a peak-hours service between Whitechapel and Baker Street. Most of the remainder of the Underground network was however operating normally.

On 2 August the Hammersmith & City line resumed normal service; the Circle line was still suspended, though all Circle line stations are also served by other lines. The Piccadilly line service resumed on 4 August.

Economic effect

There were limited reactions to the attack in the world economy as measured by financial market and exchange rate activity. The value of the British pound decreased 0.89 cents to a 19-month low against the U.S. dollar. The FTSE 100 Index fell by about 200 points during the two hours after the first attack. This was its greatest decrease since the invasion of Iraq, and it triggered the London Stock Exchange's 'Special Measures', restricting panic selling and aimed at ensuring market stability. However, by the time the market closed it had recovered to only 71.3 points (1.36%) down on the previous day's three-year closing high. Markets in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain also closed about 1% down on the day.

U.S. market indexes increased slightly, partly because the dollar index increased sharply against the pound and the euro. The Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 31.61 to 10,302.29. The NASDAQ Composite Index increased 7.01 to 2075.66. The S&P 500 increased 2.93 points to 1197.87 after decreasing as much as 1%. Every benchmark value gained 0.3%.

The market values increased again on 8 July as it became clear that the damage caused by the bombings was not as great as thought initially. By end of trading the market had recovered fully to above its level at start of trading on 7 July. Insurers in the UK tend to reinsure their terrorist liabilities in excess of the first £75,000,000 with Pool Re, a mutual insurer established by the government with major insurers. Pool Re has substantial reserves and newspaper reports indicated that claims would easily be funded.

On 9 July, the Bank of England, HM Treasury and the Financial Services Authority revealed that they had instigated contingency plans immediately after the attacks to ensure that the UK financial markets could keep trading. This involved the activation of a "secret chatroom" on the British government's Financial Sector Continuity website, which allowed the institutions to communicate with the country's banks and market dealers.

Media response

at King's Cross railway station

Continuous news coverage of the attacks was broadcast throughout 7 July, by both BBC One and ITV1, uninterrupted until 7 p.m. Sky News did not broadcast any advertisements for 24 hours. ITN confirmed later that its coverage on ITV1 was its longest uninterrupted on-air broadcast of its 50 year history. Television coverage was notable for the use of mobile telephone footage sent in by members of the public and live pictures from traffic CCTV cameras.

The BBC Online website recorded an all-time bandwidth peak of 11 Gb/s at midday on 7 July. BBC News received some 1 billion total accesses throughout the course of the day (including all images, text and HTML), serving some 5.5 terabytes of data. At peak times during the day there were 40,000 page requests per second for the BBC News website. The previous day's announcement of the 2012 Summer Olympics being awarded to London resulted in up to 5 Gb/s. The previous all time maximum for the website followed the announcement of the Michael Jackson verdict, which used 7.2 Gb/s.

On 12 July it was reported that the British National Party released leaflets showing images of the 'No. 30 bus' after it was destroyed. The slogan, "Maybe now it's time to start listening to the BNP" was printed beside the photo. Home Secretary Charles Clarke described it as an attempt by the BNP to "cynically exploit the current tragic events in London to further their spread of hatred".

Some media outside the UK complained that successive British governments had been unduly tolerant towards radical Islamist militants, so long as they were involved in activities outside the UK. Britain's reluctance to extradite or prosecute terrorist suspects resulted in London being dubbed Londonistan.

Claims of responsibility

Even before the identity of the bombers became known, former Metropolitan Police commissioner Lord Stevens said he believed they were almost certainly born or based in Britain, and would not "fit the caricature al-Qaeda fanatic from some backward village in Algeria or Afghanistan". The attacks would have required extensive preparation and prior reconnaissance efforts, and a familiarity with bomb-making and the London transport network as well as access to significant amounts of bomb-making equipment and chemicals.

Some newspaper editorials in Iran blamed the bombing on British or American authorities seeking to further justify the War on Terror, and claimed that the plan that included the bombings also involved increasing harassment of Muslims in Europe.

On 13 August 2005, quoting police and MI5 sources, The Independent reported that the bombers acted independently of an al-Qaeda terror mastermind some place abroad.

On 1 September it was reported that al-Qaeda officially claimed responsibility for the attacks in a videotape broadcast by the Arab television network Al Jazeera. However, an official inquiry by the British government reported that the tape claiming responsibility had been edited after the attacks, and that the bombers did not have direct assistance from al-Qaeda. Zabi uk-Taifi, an al-Qaeda commander arrested in Pakistan in January 2009, may have had connections to the bombings, according to Pakistani intelligence sources. More recently, documents found by German authorities on a terrorist suspect arrested in Berlin in May 2011 have suggested that Rashid Rauf, a British al Qaeda operative, played a key role in planning the attacks.

Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigades

A second claim of responsibility was posted on the Internet by another al-Qaeda-linked group, Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigades. The group had, however, previously falsely claimed responsibility for events that were the result of technical problems, such as the 2003 London blackout and the U.S. Northeast Blackout of 2003.

Conspiracy theories

A survey of 500 British Muslims undertaken by Channel 4 News found that 24% believed the four bombers blamed for the attacks did not perform them. In 2006, the government had refused to hold a public inquiry, stating that "it would be a ludicrous diversion". Prime Minister Tony Blair said an independent inquiry would "undermine support" for MI5, while the leader of the opposition, David Cameron, said only a full inquiry would "get to the truth". In reaction to revelations about the extent of security service investigations into the bombers prior to the attack, the Shadow Home Secretary, David Davis, said: "It is becoming more and more clear that the story presented to the public and Parliament is at odds with the facts." However, the decision against an independent public inquest was later reversed. A full public inquest into the bombings was subsequently begun from October 2010. Coroner Lady Justice Hallett stated that the inquest would examine how each victim died and whether MI5, if it had worked better, could have prevented the attack.

There have been various conspiracy theories proposed about the bombings, including the suggestion that the bombers were 'patsies', based on claims about timings of the trains and the train from Luton, supposed explosions underneath the carriages, and allegations of the faking of the one time-stamped and dated photograph of the bombers at Luton station. Claims made by one theorist in the Internet video 7/7 Ripple Effect were examined by the BBC documentary series The Conspiracy Files, in an episode titled "7/7" first broadcast on 30 June 2009, which debunked many of the video's claims.

On the day of the bombings Peter Power of Visor Consultants gave interviews on BBC Radio 5 Live and ITV saying that he was working on a crisis management simulation drill, in the City of London, "based on simultaneous bombs going off precisely at the railway stations where it happened this morning", when he heard that an attack was going on in real life. He described this as a coincidence. He also gave an interview to the Manchester Evening News where he spoke of "an exercise involving mock broadcasts when it happened for real". After a few days he dismissed it as a "spooky coincidence" on Canadian TV.

Investigation

Initial results

| Number of fatalities | |

|---|---|

| Aldgate | 7 |

| Edgware Road | 6 |

| King's Cross | 26 |

| Tavistock Square | 13 |

| Total number of victims | 52 |

| Suicide bombers | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 56 |

Initially, there was much confused information from police sources as to the origin, method, and even timings of the explosions. Forensic examiners had thought initially that military-grade plastic explosives were used and, as the blasts were thought to have been simultaneous, that synchronised timed detonators were employed. This hypothesis changed as more information became available. Home-made organic peroxide-based devices were used, according to a May 2006 report from the British government's Intelligence and Security Committee.

Fifty-six people, including the four suicide bombers, were killed by the attacks and about 700 were injured, of whom about 100 were hospitalised for at least one night. The incident was the deadliest single act of terrorism in the United Kingdom since the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, which killed 270 people, and the deadliest bombing in London since the Second World War.<ref>{{cite web | title = London Bomb Rescuers Were Hindered by Communications | author = Brian Lysaght and Alex Morales | url = http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aZjIrmdLQ9zo&refer=europeG

- "I'm lucky to be here, says driver". BBC. 11 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 November 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - North, Rachel (15 July 2005). "Coming together as a city". BBC. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- "Tube log shows initial confusion". BBC News. 12 July 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- "Indepth London Attacks". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Campbell, Duncan; Laville, Sandra (13 July 2005). "British suicide bombers carried out London attacks, say police". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- "BBC News - Suspected arson on 7/7 tribute bus 'Spirit of London'". Bbc.co.uk. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Samantha Badham and Lee Harris were a couple at the time.

- Image of bombers' deadly journey, BBC News, 17 July 2005. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

-

Lewis, Leo (6 May 2007). "The jihadi house parties of hate: Britain's terror network offered an easy target the security sevices missed, says Shiv Malik". The Times. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

And how could Charles Clarke, home secretary at the time, claim that Khan and his associates were "clean skins" unknown to the security services?

mirror - London bomber: Text in full, BBC, 1 September 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Video of London bomber released". Guardian. 8 July 2006.

- Video of London suicide bomber released, The Times, 6 July 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2007; a transcript of the tape is "available at Wikisource". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- "Incidents in London". United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- Lewis, Leo (17 July 2005). "Police snipers track al-Qaeda suspects". The Times Online. London. Archived from the original on 22 October 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - McCue, Andy. "7/7 bomb rescue efforts hampered by communication failings". ZDNet UK. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "London Assembly 7 July Review Committee, follow-up re port" (PDF). London Assembly. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- Lawrence, Dune (7 July 2005). "U.S. Stocks Rise, Erasing Losses on London Bombings; Gap Rises". Bloomberg. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- "Banks talked via secret chatroom". BBC News. 8 July 2005. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- "Statistics on BBC Webservers 7 July 2005". BBC Online. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- "Politics BNP campaign uses bus bomb photo". BBC News. 12 July 2005. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sciolino, Elaine; van Natta, Jr., Don (10 July 2005). "For a Decade, London Thrived as a Busy Crossroads of Terror". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- Philips, Melanie. Londonistan. Encounter Books, 2006, p. 189 ff.

- "Police appeal for bombing footage". BBC News. 10 July 2005. Archived from the original on 23 November 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Harrison, Frances (11 July 2005). "Iran press blames West for blasts". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Bennetto, Jason (13 August 2005). "London bombings: the truth emerges". The Independent. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Townsend, Mark (9 April 2006). "Leak reveals official story of London bombings UK news The Observer". Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Nelson, Dean; Khan, Emal (22 January 2009). "Al-Qaeda commander linked to 2005 London bombings led attacks on Nato convoys". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Robertson, Nic Cruickshank, Paul and Lister, Tim (30 April 2012) Documents give new details on al Qaeda's London bombings CNN.com

- Johnston, Chris (9 July 2005). "Tube blasts "almost simultaneous"". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Soni, Darshna (4 June 2007). "Survey: 'government hasn't told truth about 7/7'". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Carter, Helen; Dodd, Vikram; Cobain, Ian (3 May 2007). "7/7 leader: more evidence reveals what police knew". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Dodd, Vikram (3 May 2007). "7/7 leader: more evidence reveals what police knew". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- "7/7 bombs acts of 'merciless savagery', inquests told". BBC News. 11 October 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Honingsbaum, Mark (27 June 2006). "Seeing isn't believing". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Soni, Darshna (4 June 2007). "7/7: the conspiracy theories". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- "Unmasking the mysterious 7/7 conspiracy theorist". BBC News Magazine. 30 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Manchester Evening News "King's Cross Man's Crisis Course", 8 July 2005

- BBC4 Coincidence of bomb exercises? 17 July 2005 - Internet Archive cached version

- Intelligence and Security Committee (2006). "Report into the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005" (PDF). BBC News. p. 11.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "List of the bomb blast victims". BBC News. 20 July 2005. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- James White (11 October 2010). "7/7 bombings 'could have taken place 24 hours earlier', as inquests hear startling new details of attacks". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)