This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Arildnordby (talk | contribs) at 17:40, 17 April 2013 (Impaled hoisted up, hanging by the feet in Kabul). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:40, 17 April 2013 by Arildnordby (talk | contribs) (Impaled hoisted up, hanging by the feet in Kabul)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Impale (disambiguation).

Impalement is the penetration of an organism by an elongated foreign object such as a stake, pole, or spear, and this usually implies complete perforation of the central mass of the impaled body. In particular, techniques designed to effect penetration merely of extremities like hands or feet are excluded from this article (for such cases, see, for example, crucifixion). While the term "impalement" may be used in reference to an accident, this article has a primary focus on impalement as a form of execution, how it was performed, and highlighting some places where it was used. In particular, the article surveys impalement as a form capital punishment meted out by the judiciary, but also, secondarily, some examples from generalized massacres within the context of war, rebellion or persecution have been included. Furthermore, examples of sacrificial customs where impalement of either humans or animals has been a central element in the ritual have been included. Impalement has also been used as a way of inflicting post mortem indignities (that is, shaming the dead), or been used as a means to prevent the dead from rising from the graves, and some such examples are mentioned. Impalement has also figured in myths, legends, literature and films, and a short review of such instances is included. Finally, a few examples are given of impalement in context of animals, as in animals using impalement on prey, and hunting and preservation techniques in which impalement is a central element.

Main uses

The reviewed literature suggests that impalement across a number of cultures was regarded as a very severe punishment, as it was used particularly in response to "crimes against the state". Impalement is predominantly mentioned as punishment within the context of war, treason against "the fatherland", against some "cause" or as punishment for rebellion. As another martial example, soldiers found guilty of cowardice, or grave dereliction of duty were punished with impalement among Zulus. Disregard for the state's responsibility for safe roads and trade routes by committing highway robbery, violating state policies/monopolies, subverting standards for trade or even just involuntarily threatening public security are also recorded among offenses where impalement was occasionally used as punishment. For example, visiting Egypt for the first time 1657–58 Jean de Thévenot observed a man impaled for using false weights. For having just inadvertently threatened public security, the authorities at the Sultanate of Aceh are asserted to have instituted impalement for the crime of uncontrolled fire. At various times and places, individual murderers have been punished with impalement, either by prescribed law, or in cases regarded as particularly heinous.

Several cases show that impalement was a technique used in extrajudicial, summary executions and in massacres, or in cases of institutional religious persecution, or more generalized massacres with a religious slant. As a punishment for grave cases of religious crimes impalement was on occasion used in different parts of the world, and there are a few cases of human sacrifice by impalement. Some instances of impalement prescribed by law for adultery and other sexual crimes are also noted.

Spanish, Dutch and Portuguese colonialists are reported to have used impalement to subjugate indigenous tribes, or as a punishment meted out to slaves.

Methods

Impalement typically involves the body of a person being pierced through by a long stake, but sharp hooks, either fully penetrating the body, or becoming embedded in it, have also been used.

The stake is variably described as a sharpened wooden pole, or being tipped with iron or being called a lance, or made entirely of iron. Henry Blount, travelling the Levant in 1634, says that the three robbers he saw impaled in Egypt were impaled by their own half-pikes and that afterwards, they were bound fast, in impaled condition, to some upright stakes. One account alleges the tip of the impaling stake was rounded, rather than sharp, in order to move aside internal organs, rather than piercing and damaging them in the insertion process. Its length is reported to be from 6–15 feet,in one description as "four paces" in length. Reported thickness ranges from a man's thigh, a man's leg, a man's arm, or thick as the wrist or as thick as a foot at its thickest.

The impalement could be in the frontal-to-dorsal direction, that is, from front (through abdomen, chest or directly through the heart) to back or vice versa

Alternatively, impalement could be in the longitudinal or vertical direction, along the body length. A 17th century eyewitness account that incorporates and highlights a number of the features detailed below of the longitudinal impalement method of execution is the one given by Jean de Thevenot. The longitudinal penetration could be through the rectum, through the vagina, or through a wound opened specifically for the occasion, such as making a transverse incision to the os sacrum. In the cases where the cutting instrument is specifically mentioned, it is usually said to be a knife or razor, but a case is also recorded the wound was made with a hatchet/ax. One report says some sort of salve was used to stop the bleeding made during the cut.

The person to be impaled is generally said to have been undressed, and then been placed on his belly, face down. His hands might be tied behind his back, legs spread-eagled,. Alternatively he could be bound or held fast or sat upon by some of the executioner's assistants. In Pierre Belon's account from the 1540s, immobilization prior to impalement was effected by securing each limb to its own pole. In one case, though, it is alleged the victim was hoisted up by means of a pulley, in order to be inserted on an already erect (iron) pole.

Prior to stake insertion, some sources say the stake was greased. Typically, the actual insertion is said to have been by hammering the stake inwards by means of a mallet, with one of the executioner's team guiding the stake where he wanted it to go. However, a couple of accounts assert that the victim was gradually impaled by pulling his legs. Alternatively, as told by Stephan Gerlach who was priest for the imperial embassy at Constantinople from 1573–78, ropes were bound to the convict's feet, and after the stake has been partially inserted, typically some Christians were given the job to pull the ropes, until the stake had fully penetrated the body. While the previous notes does not mention explicitly the use of a mallet while others were pulling, Peter Mundy, staying in Constantinople from 1617 to 1620, does say exactly that. What he could hear through the throng of people surrounding the person being impaled, was "..the blowes of the Mallet, and the most horrible and fearfull Crye of the tortured Wretch". The impalement process on the Indian sub-continent seems to have been rather different than the mallet driven processes highlighted above. The shula was a "stout iron rod with a thin point on the top", presumably fixed to the ground. "The condemned person was made to sit on the top which penetrated into his body slowly and went out by the head".

The impalement could either be partial, the stake becoming embedded in the body, or a full impalement where the exit wound is variously described as being, for example, "at the nape of the neck", "at the back of his neck", "close to the shoulder" or "at the breast".

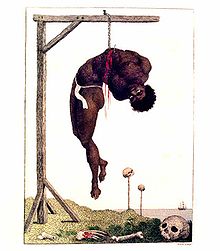

After impalement, many accounts state the pole was hoisted vertically and fixed in the ground, but one account, by Samuel Gridley Howe, being in Greece 1824-27, asserts that most were left writhing on the ground in impaled condition, and that being raised vertically was a "refined punishment" meted out to the few. Another technique of displaying the impaled is that observed by Godfrey Vigne in Kabul 1836. Here, the condemned murderer was, after impalement, hoisted up and left hanging by the feet, rather than having the impaling stake fastened in the ground.

When raised vertically, a few accounts states that the body was made to rest on a fixed plank or scaffold to avoid sliding, or that the stake and person was affixed to a wooden cross, or that the impaled legs were tied to the stake itself or that the individual's legs and arms were bound tight to adjacent poles Another source says that the victim was, at times, only partially impaled, letting the individual slide downwards on the stake on his own, due to gravity. In the Khanate of Khiva ca. 1820, the wooden stake had been, by design, left "roughly sharpened", and was only partially forced in. The idea here was that the impaled person, whose arms and legs were left free after hoisting the stake, should, by his own writhings in pain, thereby drive himself deeper onto the stake, until he died.

Whenever mentioned, the height attained by the impaled above the ground when the stake was fixed vertically is variably described. In one account, the person was "at least three feet above the ground", in another, that the stake "was too high for wild beasts to reach the body". In a third account, a ditch had been dug out prior impalement, and the stake was placed upright in that ditch, so that the person looked just like a coney on a spit, according to that author. In a fourth account, where scores of Serbs where impaled on wooden stakes on the way to Belgrade around 1810, dogs were able to gnaw at their feet. Several of the impaled lived for days. Finally, in an account where the impaled ended up sitting on a little wooden bench, that wooden bench was the top of a scaffold, some ten feet above the ground.

The survival time on the stake is quite variedly reported, from instantly or to a few minutes to a few hours or 1 to 3 days. The Dutch overlords at Batavia, present day Jakarta, seem to have been particularly proficient in prolonging the lifetime of the impaled, one witnessing a man surviving 6 days on the stake, another hearing from local surgeons that some could survive 8 or more days. A critical determinant for survival length seems to be precisely how the stake was inserted: If it went into the "interior" parts, vital organs could easily be damaged, leading to a swift death. However, by letting the stake follow the spine, the impalement procedure would not damage the vital organs, and the person could survive for several days. The actual manner used are said in some accounts to have been at the discretion of the executioners, if they wanted the person to suffer for a long time, or being mercifully quick about it. In one account, the stake was by design partially impaled into the body's interior, in such a manner that full impalement would kill him off instantaneously. After three hours suffering, the executioners killed him by simply pulling his body downwards. In that case, his intestines were quite possibly ruptured, since he was swiftly taken down after death, because he "stunk horridly".

In other cases, bystanders would be allowed to kill the victim out of mercy after a few hours on the stake. Leaving the impaled to expire on his own account, or letting others kill them out of mercy, may have been the more usual patterns. However, from 1606 Ansbach, there is preserved a receipt that not only details the expenses for the executioner, but also specifies the amount used for "refreshments" for the impaled individual.

Gaunching, and other methods

Tournefort, travelling on botanical research in the Levant 1700–02, observed both ordinary longitudinal impalement, but also a method called "gaunching", in which the condemned is hoisted up by means of a rope over a bed of sharp metal hooks. He is then released, and depending on how the hooks enter his body, he may survive in impaled condition for a few days. 40 years earlier than Tournefort, Thévenot described much the same process, adding it was seldom used, because it was regarded as too cruel.

Less usual methods of impalement have been alleged, like direct cranial impalement by driving a long nail or spike into a victim's head. The Tunisian Arab merchant Muḣammad ibn ʻUmar (1789-?) made extensive travels in his time, and relates a story of how a very unfortunate Jew is to have met his end: "A Sultan of Morocco once put a Jew in a barrel, the inside of which bristled with nails, and ordered it to be rolled down a hill" From time to time, it is recorded that "ordinary" impalement was aggravated beyond that punishment, in that the impaled individual also was roasted over a fire, for example.

Christian martyrology is replete with horror stories of how saints supposedly were martyred for their faith. Whatever truth value belongs to these tales, one particularly bad fate is said to have befallen Saint Benjamin in AD 424 Persia. According to his hagiography, when the king was apprised that Benjamin refused to stop preaching, he "...caused reeds to be run in between the nails and the flesh, both of his hands and feet, and to be thrust into other most tender parts, and drawn out again, and this to be frequently repeated with violence. Lastly, a knotty stake was thrust into his bowels, to rend and tear them, in which torment he expired...."

Behaviour of the impaled

Many accounts speak of the impaled one writhing and screaming in agony, begging passersby to kill them. A particular feature about this manner of dying is said to be to feel a "ravaging thirst" and the impaled victims are often reported begging for water. Others are reported to have been quite able to converse with people while impaled, sometimes smoking or drinking rakia on the stake as, for example, the Austrian bureaucrat Friedrich Wilhelm von Taube noted during his official inspection tour in the Kingdom of Slavonia in 1776. Some seem to have retained a grim sense of humour in their impaled condition. For example in 1714 in the Cape Colony under the Dutch, the black slave Titus, who had been the lover of his master's wife and conspired to murder her husband, was sentenced to be impaled. Four hours after being impaled, he was given some arrack to drink, but advised not too drink too much, lest he become drunk. Titus retorted that it hardly would matter, since he sat fast enough, and was in no danger of falling down.

At times, soldiers were placed on duty to prevent people from assuaging the thirst of the impaled by giving them something to drink. According to the same source, the Dutch captain Johan Splinter Stavorinus, witnessing such an execution in Batavia 1769, the impaled victim would quickly die if it began to rain, because the water entering the wound would lead to swift mortification of the flesh, and development of gangrene within "the nobler parts". The man he saw was, composed and conversing with passers by in the morning, but expired within an hour after it began raining, just three hours later than Stavorinus saw him last. During the Khmelnytsky Rebellion, in 1649 Mazyr, a Cossack rebel leader was sentenced to be impaled, and wanted to spend his last hours in communion with God. He was given drink, and his request that he might die while he heard the church bells tolling was granted. In deep prayer and to the sound of church bells, he passed away after 6 hours on the stake. Being at Tripolitsa around 1800, M. Pouqueville tells of a Greek robber chief Zacharias, who was impaled outside the city walls. Pouqueville himself had not the stomach to witness the execution, but his servant was deeply impressed by Zacharias behaviour: "He said that this robber showed a resolution beyond what had ever before been witnessed. Fixed upon the stake, in that state of torture he never ceased replying coolly to the reproaches with which he was loaded by the multitude, till an Albanian put an end to his sufferings by striking off his head." The French naturalist Sonnini was struck by the impression of the impaled along the road to Chania on Crete, which he visited in 1778:

"It is on the edge of this same road, which leads to the only gate that Canea has on the land side, that criminals, who have undergone the terrible punishment of empalement, are exposed. They are ranged on each side of the road; and in this dreadful rank are seen men whose body is longitudinally transpierced by a stake, some dead, others expiring; some smoking their pipe, with as much sang-froid as if they were sitting on cushions, railing at the Europeans, and living, as long as twenty-four hours, in the most excruciating torments."

Some of those impaled are attested to have maintained pride and defiance against their executioners. In 1666, for example, when Moulay al-Rashid conquered Fes, the previous ruler Muhammad Adridi was sentenced to be impaled. The chronicler, a supporter of al-Rashid, feels obliged to mention the obstinate pride of Adridi:

And he seized the sons of the enemy and oppressor, Muhammad Adridi, may his bones be scattered, and he hanged him and impaled him anf he gave permission for anyone who desired and wished to see him in his ugliness to go and see him (...) And come and see how proud is the evildoer Muhammad Adridiafter he has been hanged and impaled; he would say to all who saw him; once I was above you and today I am still above you

Even more remarkable is, perhaps, the defiance, pride and stoic embrace of his fate shown by the Indian chief Caupolicán who was condemned by the Spanish to be impaled in 1558. A scaffold had been erected where a sharpened wooden stake was fastened, the intention being to force Caupolicán to sit upon it. The proud chief's last act of defiance, refusing to be tortured in such an ignominous way by the approaching executioner was to kick the executioner off the scaffold, and impaled himself, without any force or assistance given to him.

Some anecdotes of the behaviour and fates of the impaled remain which, if true, would be unique in the history of impalement. The first was narrated as a proof of the efficacy of praying to Saint Barbara. In the woods of Bohemia around 1552, there was a robber band roaming, plundering and murdering innocent travelers. A manhunt was organized, and the robber chief was apprehended and sentenced to be impaled. While one of his associates, likewise impaled, swiftly expired, the chief was not so lucky. All day long, he writhed on his stake, begging to be killed, but all in vain. That night, in his despair, he prayed to St. Barbara that he was truly sorry for all his evil doings in life and that all he hoped for was to reconcile with God and to be graced with a good death. Seemingly in response, the man's stake broke, and with great effort and pain, he managed to de-impale himself. Crawling along, he came to a house, and his cries of help were heard. He was helped into a bed, and a priest was sent for. The former robber chief then gave his death bed confession, grieving over his misspent life, but properly grateful to God and St. Barbara. He then died in peace, his hands folded over his chest.

Another incident, which was, allegedly, partially witnessed by the editor of a "Ladies' Journal", is said to have occurred in Wallachia in the 1770s. He had been present in Arad when 27 robbers had been impaled. It was strictly forbidden to give the impaled persons any water, but one woman took mercy on one of the robbers, and fetched water for him in a kettle. As she was glancing anxiously about to check if anyone took notice of her forbidden act of mercy, the robber smashed her head in with the kettle, killing her on the spot. The editor avers he was present when the robber was asked why he had done such a thing, and he merely replied he had done it on a whim, and just had felt like killing her then and there.

Rituals of impalement

Execution as pageantry

The execution of a human being has not always been only the mere killing of that person, but also a carefully staged ritual prior to, during and after the execution act. For example, both the chaplain at Aleppo, Henry Maundrell, who left a travel account from 1697, and the Scottish physician and naturalist Alexander Russell staying there 1740–54 note a local custom in which those criminals condemned to be impaled had to carry their own stakes to the execution site. Commenting further on the local execution rites one still notorious pasha had staged as he toured the country around Aleppo to distribute justice, Russell writes:

"The bodies however were not permitted to be taken down, and remained a horrid and offensive spectacle. It was the custom of that Bashaw, when he travelled, to carry malefactors, already condemned, along with him, and to empale one at every stage, leaving them to be devoured by the birds of prey, as the stake was too high for wild beasts to reach the body. His frequent exercise of this punishment, procured him the title of Hasookgee, or Empaler"

Refusing an executed criminal to be buried within the culturally perceived appropriate time of burial after death, and instead leaving the body exposed to rot or be devoured are ways to shame the dead that are quite often reported for victims of impalement, across a range of cultures. Although shaming the dead, and also to provide a deterrent for potential evil-doers by letting the bodies remain on public display beyond the proper burial time for non-criminals is well attested, different cultures exbibit debates on what is a proportionate post mortem punishment for the criminal, and what would exceed the bounds of propriety, even for them. For example, the 12th century Hanafi scholar Burhan al-Din al-Marghinani in his highly influential Al-Hidayah thinks it is impermissible that the body should remain on display beyond 3 days, regarding the exposed rotting process of the criminal to be forbidden, and dismisses those jurists who think the body must be left to rot publicly for deterrence effect by thinking "sufficient" deterrence is given by 3 days display.

- Trampling on the dead

Sometimes, however, the shaming of the dead seems to have gone beyond any "proper" degree of shaming, into a calculated display of maximal indecency and contempt for the deceased. One such example is from English history:

John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester reportedly had twenty men, found guilty of rebellion against King Edward IV, hanged, drawn and quartered. Each corpse was beheaded and hung by the legs. Then stakes sharpened at both ends were used, so that one of the ends was pushed into the anus, and the severed head was then placed on the remaining free end. For this act, the chronicler remarks, he became deeply hated by the people for acting contrary to the laws of the land, and Tiptoft was later executed at the Tower of London

- Mass executions and spectacles of horror

Occasionally, impalement has been an element in grand spectacles of horror, in which a large number are executed, often with other types of grievous punishments recorded as well. Some examples are:

Cassius Dio relates the following story of how Romans, and those collaborating with them were massacred during Boudicca's revolt:

"Those who were taken captive by the Britons were subjected to every known form of outrage. The worst and most bestial atrocity committed by their captors was the following. They hung up naked the noblest and most distinguished women and then cut off their breasts and sewed them to their mouths, in order to make the victims appear to be eating them; afterwards they impaled the women on sharp skewers run lengthwise through the entire body."

In ancient Tamil Nadu, in present-day India, impaling was referred to as Kazhuvetram. A notorious episode from Tamil Nadu, under the old Pandyan Dynasty, ruling from 500 BC- 1500 AD, the 7th century King Koon Pandiyan had 8000 Jains impaled. This act is still commemorated in "lurid mural representations" in several Hindu temples in Tamil Nadu. In that particular case, the Jains were massacred for blasphemy, for having taken the name of Shiva in vain. An example of such depictions in temples can be found in the Meenakshi Amman Temple in Madurai, around the holy tank enclosure to the shrine of Meenakshi. There, a long line of impaled Jaines are depicted, with dogs at their feet, licking up the blood, and crows flying around to pick out their eyes.

The Mughal emperor Jahangir made his rebellious son Prince Khusrau Mirza ride an elephant down a street lined with stakes on which the rebellious prince's supporters had been impaled alive. In his purported memoirs, Jahangir writes:

"In the course of the same Thursday I entered the castle of Lahour, where I took up my abode in the royal pavilion built by my father on this principal tower, from which to view the combats of elephants. Seated in the pavilion, having directed a number of sharp stakes to be set up in the bed of the Rauvy, I caused the seven hundred traitors who had conspired with Khossrou against my authority to be impaled alive upon them. Than this there cannot exist a more excruciating punishment, since the wretches exposed frequently linger a long time in the most agonizing torture, before the hand of death relieves them; and the spectacle of such frightful agonies must, if any thing can, operate as a due example to deter others from similar acts of perfidy and treason towards their benefactors."

Human sacrifice

The Greek historian Herodotus avers that at the anniversary of a great Scythian king's death, a grand ritual of human and animal sacrifice was performed, where (post mortem) impalement was a critical factor in order to get the desired effect:

"When a year is gone by, further ceremonies take place. Fifty of the best of the late king's attendants (...) are taken, and strangled, with fifty of the most beautiful horses. When they are dead, their bowels are taken out, and the cavity cleaned, filled full of chaff, and straitway sewn up again. This done, a number of posts are driven into the ground, in sets of two pairs each, and on every pair half the felly of a wheel is placed archwise ; then strong stakes are run lengthways through the bodies of the horses from tail to neck, and they are mounted up upon the fellies, so that the felly in front supports the shoulders of the horse, while that behind sustains the belly and quarters, the legs dangling in mid-air ; each horse is furnished with a bit and bridle, which latter is stretched out in front of the horse, and fastened to a peg. The fifty strangled youths are then mounted severally on the fifty horses. To effect this, a second stake is passed through their bodies along the course of the spine to the neck; the lower end of which projects from the body, and is fixed into a socket, made in the stake that runs lengthwise down the horse. The fifty riders are thus ranged in a circle round the tomb, and so left"

Captain John Adams, visiting Lagos in 1789, spits out his disgust at "horrid customs" writing about a local practice of sacrificing a young virgin to propitiate the rain goddess:

"The horrid custom of impaling alive a young female, to propitiate the favour of the goddess presiding over the rainy season, that she may fill the horn of plenty, is practised here annually. The immolation of this victim to superstitious usage takes place soon after the vernal equinox; and along with her are sacrificed sheep and goats which, together with yams, heads of maize, and plantains, are hung on stakes on each side of her. Females destined thus to be destroyed, are brought up for the express purpose in the king's or caboceer's seraglio; and it is said, that their minds have previously been so powerfully wrought upon by the fetiche men, that they proceed to the place of execution with as much cheerfulness as those infatuated Hindoo women who are burnt with their husbands. One was impaled while I was at Lagos, but of course I did not witness the ceremony. I passed by where the lifeless body still remained on the stake a few days afterwards."

Regional and other historical studies

Archaic age/Antiquity

The earliest known use of impalement as a form of execution occurred in civilizations of the Ancient Near East. For example, the Code of Hammurabi, promulgated about 1772 BC by the Babylonian king Hammurabi specifies impaling for a woman who killed her husband for the sake of another man. Only two instances of impalement used in military context by Egyptians are attested; once by under the pharaoh Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BC), where he once had 80 Kushites impaled during a campaign and once under Merneptah (r.1213-1203 BC). Otherwise, Egyptians reserved impalement as a punishment for severe religious crimes, in particular for tomb robbery.

From the Middle Assyrian period, around 1500-1000BC, the law code discovered and deciphered by Dr. Otto Schroeder contains in its paragraph 51 the following injunction against abortion: "If a woman with her consent brings on a miscarriage, they seize her, and determine her guilt. On a stake they impale her, and do not bury her; and if through the miscarriage she dies, they likewise impale her and do not bury her" Evidence by carvings and statues is found as well, for example from Neo-Assyrian empire. For the Neo-Assyrians, mass executions seem to have been not only designed to instill terror and to enforce obedience, but also, it can seem, as proofs of their might that they took pride in. For example, Neo-Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II was evidently proud enough of his bloody work that he committed it to monument and eternal memory as follows:

"I cut off their hands, I burned them with fire, a pile of the living men and of heads over against the city gate I set up, men I impaled on stakes, the city I destroyed and devastated, I turned it into mounds and ruin heaps, the young men and the maidens in the fire I burned"

Nor is this particular commemoration of massacre anything unique in Ashurnasirpal II's reign, but rather, a variation on the theme of self-glorification due to proved might and will to effect large scale destruction of human beings. For example, Charles Boutflower, in an essay devoted to elucidate the meaning of the word "asitu" (something like "tower", or "mound"), cites the commemoration Ashurnasirpal II made in honour to himself for the massacre of the subjects of Aziel, a ruler of a small kingdom on the middle Euphrates:

I built an "asitu" at the entrance to his city gate; the chief men, as many who had rebelled against me, I flayed, and covered the "asitu" with their skins. Some I walled up within the "asitu", others I impaled on stakes upon the "asitu", others again I fixed on stakes around the "asitu"

A peculiarity about the Assyrian way of impaling was that the stake was "driven into the body immediately under the ribs", rather than along the full body length.

- The Bible

In the Bible, II Samuel 21:9, we read

- "And they handed them over to the Gibeonites, and they impaled them ויקיעם on the mountain before YHVH, and all seven of them fell together. And they were killed in the first days of the harvest, at the beginning of the barley harvest."

Some controversy exist concerning the actual fate of the 5th century BC Persian minister Haman and his ten sons, whether they were impaled or hanged (Haman conspired to have all the Jews in the empire killed, the Book of Esther tells that story, and how Haman's plan was thwarted, and he was given the punishment he had thought to mete out to Mordecai). For example, in the English Standard Version, Esther 5:14 reads:

"..and all his friends said to him, “Let a gallows fifty cubits high be made, and in the morning tell the king to have Mordecai hanged upon it. Then go joyfully with the king to the feast.” This idea pleased Haman, and he had the gallows made."

The New International Reader's version, however, reads:

"They said to him, “Get a pole. In the morning, ask the king to have Mordecai put to death. Have the pole stuck through his body. Set it up at a place where it will be 75 feet above the ground. Everyone will be able to see it there. Then go to the dinner with the king. Have a good time.” Haman was delighted with that suggestion. So he got the pole ready."

The Assyriologist Paul Haupt opts for impalement in his 1908 essay "Critical notes on Esther", while Benjamin Shaw has an extended discussion of the topic on the website ligonier.org from 2012 Although conclusive evidence might be wanting either way, the Neo-Assyrian method of impalement as seen in the carvings could, perhaps, equally easily be seen as a form of hanging upon a pole, rather than focusing upon the stake's actual penetration of the body.

- Roman Empire

In ancient Rome, the term "crucifixion" could also refer to impalement. This derives in part because the term for the one portion of a cross is synonymous with the term for a stake, so that when mentioned in historical sources without specific context, the exact method of execution, whether crucifixion or impalement, can be unclear. In his funerary inscription Res Gestae Divi Augusti recording what he thought of his most notable achievements, Emperor Augustus highlights that he had ordered those slaves impaled (out of roughly 30.000 or so) who did not return to their masters after the civil wars period preceding his reign.

Africa

Thomas Shaw, who was chaplain for the Levant Company stationed at Algiers during the 1720s, differentiates between punishments meted out to different population groups, impalement primarily being used as a form of capital punishment for Arabs and Moors:

"When a Jew or a Christian slave, or subject is guilty of murder, or any other capital crime, he is carried without the gates of the city, and burnt alive: but the Moors and Arabs are either impaled for the same crime, or else they are hung up by the neck, over the battlements of the city walls, or else they are thrown upon the chingan or hooks that are fixed all over the walls below, where sometimes they break from one hook to another, and hang in the most exquisite torments, thirty or forty hours. The Turks are not publickly punished, like other offenders. Out of respect to their characters, they are always sent to the house of the Aga, where, according to the quality of the misdemeanor, they are bastinadoed or strangled."

According to one source, these hooks in the wall as an execution method were introduced with the construction of the new city gate in 1573. Before that time, gaunching as described by de Tournefort was in use. Laurent d'Arvieux, who was French consul in Algiers in 1674-75, says the hooks were spaced closely, resembling fishing hooks. Those thrown on the hooks were, according to him, typically Moors, or rebels and traitors, or those who were thought to deserve long torments. He also notes that the convict was usually bound hands and feet prior to being thrown off the wall, and if he was unlucky enough to survive for a few days, his body would typically begin rotting prior to death. Taken captive in 1596, the barber-surgeon William Davies relates something of the heights involved when thrown upon hooks (although it is somewhat unclear if this relates specifically to the city of Algiers, or elsewhere in the Barbary States): "Their ganshing is after this manner: he sitteth upon a wall, being five fathoms high, within two fathoms of the top of the wall; right under the place where he sits, is a strong iron hook fastened, being very sharp; then he is thrust off the wall upon this hook, with some part of his body, and there he hangeth, sometimes two or three days, before he dieth."

As for the actual frequency of throwing persons on hooks in Algiers, Capt. Henry Boyde, in one of his acerbic comments and footnotes to translated accounts from Catholic priests' narratives of the redemption of slaves notes that in his own 20 years there, he knew of only one case where a Christian slave who had murdered his master had met that fate, and "not above" two or three Moors besides. Even as close in time to the 1720s observations of Thomas Shaw and Henry Boyd, the 1730s-40s writer and compilator Thomas Salmon observes that it is "many years" since anyone were thrown upon the hooks. This discontinuation seems to have been not only a temporary respite, since 60 years later than Shaw, in a 4-year stay around 1789 in Algiers, Johann von Rehbinder notes that throwing people on hooks, the "chingan" mentioned by Shaw, is a wholly discontinued practice in Algiers, and that burning of Jews had not occurred during his residence there.

Americas

While practically all instances of use of stakes designed to impale other human beings can be thought of as acts of aggression, either within the context of war, or as a punishment meted out to criminals deemed deserving of it, some Amazon tribes developed a use of stakes meant primarily as a defensive measure. In a review of Thomas Whiffen's account of his 1908-09 exploration, we read: "For defense the Indians depend mainly upon the secrecy of the tribal dwelling, an easy matter in the absence of direct foot-paths. In addition, each tribe prepares a series of pit-falls in the forest avenues with poison stakes to impale the foe". Some centuries earlier, in other parts of the Americas, in the sixteenth century, the Spanish conquistadores were exasperated at the "very crude warfare" some of the Indians made: They covered deep pits with stakes on the bottom, upon which many Spaniards and their horses were impaled. The Spanish in the sixteenth century did not just meet "crude warfare" in the shape of mere pit traps, though. As the Aztec Empire crumbled in the 1520s and the Spanish gradually extended their sway northwards, allying with some tribes, enslaving others (for work in the silver mines, for example), in the middle century, they met a "scourge (...) so strong that Spaniards tremble at the mere mention of them". That scourge was the largely nomadic indigenous tribes of Northern Mexico, loosely called the Chichimecas. For the next four decades, these embittered foes of the Spanish made lightning swift, devastating raids. Their cruelty was legendary, steeling the Spanish and their allies into both a propaganda, and an extermination war against them. Among the Chichimecas noted cruelties were to chop off men's genitalia and stuff them into the victim's mouth, or slow dismemberment of a captive, removing one body part at a time (a leg, a an arm, or just a rib), until the captive died. They were also alleged to impale their captives "as the Turks do".

A particular technique devised by the Dutch overlords in Suriname was to hang a slave from the ribs. John Gabriel Stedman stayed there from 1772–77 and described the method as told by a witness:

"Not long ago, (continued he) I saw a black "man suspended alive from a gallows by the ribs, between which, with a knife, was first made an incision, and then clinched an iron hook with a chain: in this manner he kept alive three days, hanging with his head "and feet downwards, and catching with his tongue the "drops of water (it being in the rainy season) that were "flowing down his bloated breast. Notwithstanding all this, he never complained, and even upbraided a negro "for crying while he was flogged below the gallows, by calling out to him: "You man ?—Da boy fasy? Are you a man? you behave like a boy". Shortly after which he was knocked on the head by the commiserating sentry, who stood over him, with the butt end of his musket"

It was not only the Dutch who resorted to extreme forms of penalties if slaves revolted or murdered, and from what became USA, several cases exist where slaves were burnt alive if they transgressed. In one New York case from 1708, two slaves found guilty of murdering a white family were sentenced to be put to death by "all manner of torment possible". One of them was burned alive over a slow fire, and the other was partially impaled and then hung alive in chains in order to prolong his suffering for hours.

Eunice Cole, or "Goody" Cole (ca 1590-1680) was a woman in New Hampshire widely reputed to be a witch, and was several times jailed for "slanderous speech" and other offences. Legend has it that when she died, "her body was dragged outdoors, pushed into a shallow grave, and a stake driven through it in order to exorcise the baleful influence she was supposed to have possessed."

Asia

- Near East

Reportedly, members of the Alawite sect centered around Latakia in Syria had a particular aversion towards being hanged, and the family of the condemned was willing to pay "considerable sums" to ensure their relation was impaled, instead of being hanged. As far as Burckhardt could make out, this attitude was based upon the Alawites' idea that the soul ought to leave the body through the mouth, rather than leave it in any other fashion.

On the other hand, the mid-17th century merchant and traveller Laurent d'Arvieux became witness to an Arab robber who begged to be spared of impaling, asking to be flayed alive instead. The reason was that that had been the fate of his father and grandfather, so he wanted to die like them. His request was granted.

In 1838, Faisal bin Turki bin Abdullah Al Saud was ousted from the throne by Egyptian intrigues, and Khalid ibn Saud from the senior Saudi line was installed as pasha. He, however, became deeply hated for introducing punishments like impaling in the Nejd, and in 1840, he was replaced by Abdullah ibn Thuniyyan. If anything, the new ruler intensified the use of impaling and became even more hated than Khalid, preparing the takeover in 1843 by Faisal yet again.

- Indian sub-continent

A case in point where we have several explicit law codes or alleged general laws concerning punishments in general, and impalement in particular, is the Indian sub-continent. In the Mahabharata, it is said that the (mythical) king Ugrasena ordained that wine drinking was to be forbidden, on pain of impalement. The old, yet historical, Bengali law code Arthashastra (composed between the 4th century BC and 200 AD), specifies the following crimes as punishable by impalement, or suka: murder with violence, infliction of undeserved punishment, spreading of false reports, highway robbery, and theft of or wilful injury to the king's horse, elephant or chariot. In the celebrated Laws of Manu, paragraph 276 states: "Of robbers, who break a wall or partition, and commit theft in the night, let the prince order the hands to be lopped off, and themselves to be fixed on a sharp stake." The 3rd-5th century law code Yājñavalkya Smṛti stipulates that he who rescues a prisoner should be impaled. In early 16th century Malabar, on authority Ludovico di Varthema, who visited there in the first decade of the century, the prescribed law for murder was impalement. Fernão Nunes, being 1535-37 in the Vijayanagara Empire that covered the southern part of present day India notes that nobles found guilty of treason had a wooden stake pushed through their belly. (He also mentions that those found guilty of great theft or having raped a respectable woman or virgin would be hanged up by means of a hook impaled through his chin.) Judicial ideas concerning the punishment of impalement did, of course, vary over time, and from place to place, on the Indian sub-continent. For example, the emperor Akbar, in his 16th century regulations on the proper conduct of magistrates, says explicitly that the magistrate should not suffer anyone to be impaled (along with other such humane commands, for example to ensure that no widows were to be burnt alive unwillingly, and that no boy should be circumcised before the age of 12, after which it should be the boy's own decision). His son, Jahangir, however, had no scruples reinstating the punishment, also on the level of mass execution.

The ascendancy of the British as rulers in India did not spell an abrupt end to punishments like impalement, and Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal from 1772-1785 even gave his formal approval to four cases of impalement in 1781.

- Vietnam

During the Vietnam War of the late 1960s, one account alleges that a village headman in South Vietnam who cooperated in some way with the South Vietnamese Army or with U.S. soldiers might have been impaled by local Viet Cong as a form of punishment for alleged collaboration. The method of impalement was alleged to have been the insertion of a sharpened stake through the anus; the stake was then supposedly planted vertically in the ground in view of his village. The victim was allegedly tortured and humiliated by complete castration, with the amputated genitalia being forced into his mouth. Another account alleges that the pregnant wife of a village headman was vertically impaled. There is also an allegation from the Vietnam War of coronal cranial impalement. In this case, a bamboo stake was supposedly thrust into the victim's ear and driven though the head until it emerged from the opposite ear opening. The act was allegedly perpetrated on three children of a village chief near Da Nang.

Impalement and other methods of torture were intended to intimidate civilian peasants at a local level into cooperating with the Viet Cong or discourage them from cooperating with the South Vietnamese Army or its allies. The main culprits for the use of impalement appear to be members of the Viet Cong of South Vietnam. No allegations have been made against soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), nor is there any evidence that either the NVA or the government in Hanoi ever condoned its use.

- Japan

Impalement was only occasionally used by samurai leaders during the Age of Warring States. Early in 1561, the allied forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga defeated the army of the Imagawa clan in western Mikawa province, encouraging the Saigo clan of east Mikawa, already chafing under Imagawa control, to defect to Ieyasu's command. Incensed at the rebellious Saigo clan, Imagawa Ujizane entered the castle-town of Imabashi, arrested Saigo Masayoshi and twelve others, and had them vertically impaled before the gate of Ryuden Temple, near Yoshida Castle. The deterrent had no effect, and by 1570, the Imagawa clan was stripped of its power.

Europe

- England, Edward II and the shaming of suicides

It has long been believed that Edward II (1284–1327) was impaled by a heated poker thrust into his anus. This is, for example, contained in Christopher Marlowe's play Edward II (c. 1592). That story of Edward II's death can possibly be traced back to the late 1330s; however, the very earliest accounts of Edward's demise do not corroborate impalement, but speak instead of death by illness or suffocation. It is generally accepted by historians that he was murdered by an agent of his wife, Isabella, on 11 October 1327 in Berkeley Castle.

Not formally abolished until 1823, suicide victims and anyone killed during the commission of a crime could be punished post mortem with impalement. The law designated these deaths as felo de se ("felony against the self") and declared the dead person's movable property forfeit to the Crown (but not his lands). The body was buried at an unconsecrated location and early ecclesiastical law, like that of King Edgar in 967, forbade celebrating mass for the soul, nor commit his body to the ground with hymns or other rites of "honourable sepulture". The burial location was usually at a crossroads or highway. In some locations, a stake was driven through the corpse's heart. Following William Blackstone's reasoning, Moore is explicit upon that public shaming of the self-murderer is an important part of this tradition:

"By virtue of this authority the body of the self-murderer is cast with the burial of a dog into an hole dug in some public highway, which fulfils the law in this point. But in some places an additional (though not an enjoined) ignominy is practised, which consists in driving a stake through the body, and also inscribing the name and crime on a board above—" as a dreadful memorial to every passenger, how "he splits on the rock of self-murder.""

No evidence has surfaced in which impaling alive has been sanctioned by written law in Britain, although some examples of alleged practice are attested from British history. In addition, during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, one British general became so incensed that he asked for permission to impale rebels (although it does not seem it was granted, or carried out).

- Holy Roman Empire and Switzerland, custom of live burial+impalement

In the Holy Roman Empire, there existed a curious execution method of combined premature burial and impalement. While article 131 in the 1532 Constitutio Criminalis Carolina recommended that women guilty of infanticide should be drowned, the law code allowed for, in particularly severe cases, that the old punishment could be implemented: that is, the woman would be buried alive, and then a stake would be driven through her heart. Cases from the 15th/ early 16th century show that not only women found guilty of infanticide could be punished in this manner, but also women guilty of theft.

In some Landrechte and city statutes, like that for Husum in 1608, live burial and impalement is prescribed for parents who murder their children, or vice versa. At times, the impalement might precede the burial, as shown in a very late case from 1686. A woman strangled her newborn, and she was executed by impaling a stake directly through her heart. As a post mortem punishment for women found guilty of infanticide, the custom of driving a stake through the body was kept active even later, in some places. For example in 1738, it is reported that in Bohemia, such women had a stake driven through their hearts, after they had been beheaded.

While it seems that execution by impalement following live burial was primarily a punishment for female criminals, it is also attested for rapists of virgins. In one description, the rapist was placed in an open grave, and the rape victim was ordered to make the three first strokes on the stake herself; the executioners then finishing the impalement procedure.

The 1. August 1465 in Zurich, Switzerland, Ulrich Moser was condemned to be impaled, for having sexually violated 6 girls between the ages four and nine. His clothes were taken off, and he was placed on his back. His arms and legs were stretched out, each secured to a pole. Then a stake was driven through his navel down into the ground. Thereafter, people left him to die. Throughout the 400 years 1400–1798, this is the only known execution by impalement in Zürich, out of 1445 recorded executions.

Impalement was, on occasion, combined with other execution methods than live burial prevalent in the empire, in cases perceived to be of a particularly heinous nature. In 1600 Bavaria, the Pappenheimer family went on trial for having murdered and dismembered numerous children for the purposes of witchcraft. Prolonged torture brought confession of these and other crimes. The patriarch Paulus was condemned to the rarely used longitudinal impalement, and the criminally culpable family members (after the men had had their arms broken, and the mother Anna having her breasts sliced off) were dragged on top an enornous pile of brushwood that was set on fire. The 11-year old son was forced to watch the execution of his family, and he saw his mother writhe in agony, he screamed out: "My mother is squirming"

In Breslau 1615 a man confessed, after torture, to 96 acts of murder (including cutting up some pregnant women) and severals acts of arson and theft. He was sentenced to be pinched several times with glowing pincers, then be broken on the wheel, and finally to be impaled. The chronicler remarks the man showed "unbelievable composure" during this horrific execution, and adds that he even was able to speak after being impaled.

- Wallachia, the case of Dracula

During the 15th century, Vlad III, Prince of Wallachia, is credited as the first notable figure to prefer this method of execution during the late medieval period, and became so notorious for its liberal employment that among his several nicknames he was known as Vlad the Impaler. After being orphaned, betrayed, forced into exile and pursued by his enemies, he retook control of Wallachia in 1456. He dealt harshly with his enemies, especially those who had betrayed his family in the past, or had profited from the misfortunes of Wallachia. Though a variety of methods was employed, he has been most associated with his use of impalement. The liberal use of capital punishment was eventually extended to Saxon settlers, members of a rival clan, and criminals in his domain, whether they were members of the boyar nobility or peasants, and eventually to any among his subjects that displeased him. Following the multiple campaigns against the invading Ottoman Turks, Vlad would never show mercy to his prisoners of war. The road to the capital of Wallachia eventually became inundated in a "forest" of 20,000 impaled and decaying corpses, and it is reported that an invading army of Turks turned back after encountering thousands of impaled corpses along the Danube River. Woodblock prints from the era portray his victims impaled from either the frontal or the dorsal aspect, but not vertically. As an example of how Vlad Tepes soon became iconic for all horrors unimaginable, the following pamphlet from 1521 pours out putative incidents like this one:

"er liess kinnder praten die musten ire mütter essen. Und schneyd den frawen den prüst ab den musten ire man essen. Darnach liess er sie all spissen."

He let children be roasted; those, their mothers were forced to eat. And (he) cut off the breasts of women; those, their husbands were forced to eat. After that, he had them all impaled

- Russia, tradition of rebellion and suppression thereof

In medieval Russia impalement in its traditional way was sometimes used as a punishment for some serious crimes or, more commonly, for treason. In particular, there are some evidences of this penalty being used during the reign of Ivan the Terrible. For example, the Elizabethan diplomat and traveller Jerome Horsey notes how swift the wheels of fortune turned for one nobleman, Boris Telupa, from being a great favourite, to ending his life on the stake Faced with serious revolts, the Czars' suppressions could be extremely bloody. For example, the following is told of how Stenka Razin's rebellion was crushed:

"In November, 1671, Astrakhan, the last bastion of the rebels, fell. The participants of the revolt were subject to severe repressions. Trained troops hunted down exhausted and fleeing rebels, who were impaled on stakes, nailed to boards, torn to shreds, or flogged to death. 11 thousand people were executed in the town of Arzamas alone."

In 1698, when Peter the Great was on his great European tour, the military contingent known as the Streltsy chose to rebel, in favour of Peter's half-sister Sophia. Peter rushed back, and quelled the revolt brutally, with several implicated impaled. Eugene Schuyler, in his biography of the czar shows the level of anxiety in Peter during the 1707–08 Cossack revolt under Bulavin

"He ordered Prince Basil Dolgoruky (...) to march against the insurgents and "put out the fire once for all", ' burning villages and impaling and breaking on the wheel the inhabitants in order to deter the wavering from rebellion.' He recommended him to study the history of the rebellion of Stenka Razin,(...) His letter ended with the phrase: "These locusts cannot be treated otherwise than with cruelty". In another letter written at a cooler moment he recommended Dolgoruky to treat the repentant with clemency, and not to use blind terrorism..

As Eugene Schuyler remarks, "Dolgoruky was in great perplexity", not the least due to his emperor's changing instructions.

A notable execution outside wartime in Peter's reign is recorded in 1718, when he ordered Stepan Glebov, the lover of Peter's ex-wife Eudoxia Lopukhina, to be impaled publicly as a traitor. Just a few years later, in 1722, when Peter the Great demanded an oath of allegiance from his subjects, tumults broke out in the little Siberian town Tara by the Irtysh river, and 700 men are said to have been impaled alive in one day. In 1739, a peasant conceived the idea that he was, actually, Alexei Petrovitch, the son of Peter the Great, who had died in 1718 in dismal prison conditions on his father's suspicion he was trying to supplant him. The peasant in 1739 did not get much of a following, but he earned for himself the punishment of being impaled alive for his attempt at the crown.

According to some sources, punishments like impalement through the side and hanging people from the ribs were first discontinued under Empress Elizabeth (reign 1741–62). In the same vein, in 1754, Elizabeth abolished de facto, if not de jure, the death penalty in Russia, except for cases of treason. That attitudes towards impalement as punishment had changed considerably in imperial circles by the latter half of the 18th century is readily seen in the aftermath of the 1774–75 Pugachev's rebellion. While the rebels impaled the governor of Dmitrefsk in 1774, in addition to the astronomer Lowitz, Pugachev himself was merely beheaded. The effective abolition of the death penalty under Elizabeth is all the more remarkable considering that just a few decades earlier, under Peter the Great, the number of offenses meritable by death (by various means) had increased from the roughly 60 in 1649 to 123 different types of offenses. Also, under Peter the Great, the number of executions reached unprecedented levels, with, occasionally, more than a thousand executed per month.

Byzantine Empire

Impalement was used by the Byzantine Empire against various groups.

Deserted soldiers would be thrown to wild animals or impaled. On authority of Procopius, the general Belisarius once had a couple of soldiers impaled for some crimes. When the army muttered, Belisarius retorted:

"Know that I am come to fight with the Arms of Religion and Justice(..) I will never suffer that Man in my Army whose fingers are stain'd with Blood, though he be a Mars in war. Force without Justice and Equity is Cowardice, not Valour"

From 821-23, Thomas the Slav led a large scale rebellion/civil war against Michael II. Besieged in Arcadiopolis, Thomas' troops finally yielded, and delivered him up to the emperor. Michael II ordered Thomas' hands and feet to be cut off, and then to be impaled. Enemy soldiers could also be impaled as happened to a group of captured Saracen raiders in 1035. They were impaled along the coastline from Adramytion to Strobilos. In 880 the crews and soldiers of some Byzantine ships who deserted during an Arab raid in southern Greece were paraded with ignominy through Constantinople and impaled. Emperor Basil II impaled captured rebel commanders in 989. At the beginning of 1185 emperor Andronikos I Komnenos stoned and impaled two relatives of Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire used impalement during, and before, the last Siege of Constantinople in 1453. For example during the buildup phase to the great siege the year before, in 1452, the sultan declared that all ships sailing up or down through the Bosphorus had to anchor at his fortress there, for inspection. One Venetian captain, Antonio Rizzo, sought to defy the ban, but his ship was hit by a cannon ball. He and his crew were picked up from the waters, the crew members to be beheaded (or sawn asunder according to Niccolò Barbaro), whereas Rizzo was impaled.

Impalement seems to have been mostly used against perceived rebels during some of the more brutal repressions of nationalistic movements, such as reprisals following insurrections in Greece and other countries of Southeast Europe, or against Kurdish or Arab subjects. Highway robbers were still impaled into the 1830s, but one source says the practice was rare by then. Travelling to Smyrna and Constantinople in 1843, Stephen Massett was told by a man who witnessed the event, that "just a few years ago", a dozen or so robbers were impaled at Adrianople. All of them, however, had been strangled prior to impalement. Writing around 1850, the archaeologist Austen Henry Layard mentions that the latest case he was acquainted with happened "about ten years ago" in Baghdad, on 4 rebel Arab sheikhs. Massett says that even executions in general, and not just impalement, had become rare in Turkey at his time, and that the one happpening when he was there caused more of a stir than what would have happened in the USA. These observations from various travellers may be viewed in connection with the judicial reforms instigated under sultan Mahmud II. Writing in "Das Ausland" in 1839, M. d'Anbignose notes that a principal reform Mahmud II was to severely limit the governors' powers to independently decide upon, and execute the death penalty. As an illustration of Mahmud II's personal unwillingness to implement the death penalty, he notes that from October 1836 to May 1838, the sultan only ratified two death penalties. Charles MacFarlane, revisiting after 20 years absence Turkey in 1847 not only confirms the decreased frequency of executions, but also a marked change in the mentality to such spectacles (at least in Constantinople), in the case where the clerics pushed through a beheading of an apostate from Islam:

..the young Sultan was known to be averse to his execution, but the Sheik ul Islam, and all the fanatics of Constantinople, insisted that, in so solemn a case as this, the law must take its course; and in the end, the poor Armenian was led out to be executed. But instead of running to the horrid spectacle and exulting at it, the Turks ran away from the spot, and shut themselves up in their houses, and the man who was constrained to act the part of executioner fainted when he had performed his office. Twenty years ago heads were cut off with gaieté de coeur

It should not be presumed, however, that impaling, or even crime itself, was very common in the Ottoman empire in previous centuries, either (Charles MacFarlane says crime actually had increased quite sharply since his first visit in 1828). For example, Aubry de La Motraye, lived in the realm for 14 years from 1699 to 1713 and claimed that he hadn't heard of twenty thieves in Constantinople during that time. As for highway robbers, who sure enough had been impaled, Aubry heard of only 6 such cases during his residence there. Staying at Aleppo from 1740–54, Alexander Russell notes that in the 20 years gone by, there were no more than "half a dozen" public executions there. Jean de Thévenot, traveling in the Ottoman Empire and its territories like Egypt in the late 1650s emphasizes the regional variations in impalement frequency. Of Constantinople and Turkey, de Thévenot writes that impalement was "not much practiced" and "very rarely put in practice". An exception he highlighted was the situation of Christians in Constantinople. If a Christian spoke or acted out against the "Law of Mahomet", or consorted with a Turkish woman, or broke into a mosque, then he might face impalement unless he converted to Islam. In contrast, de Thévenot says that in Egypt impalement was a "very ordinary punishment" against the Arabs there, whereas Turks in Egypt were strangled in prison instead of being publicly executed like the natives. Thus, the actual frequency of impalement within the Ottoman Empire varied greatly, not only from time to time, but also from place to place, and between different population groups in the empire. Caution should also be kept against assumptions of general simultaneous decline in impaling, for widely different types of perceived crime. For example, although the heyday of impalement as a regular execution method for highway robbers and the like within the Ottoman Empire may have petered out about 1840 or so, historian James J. Reid, in his "Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839-1878" notes several instances of later use, in particular in times of crises, and ordered by military commanders. As examples, he notes late instances of impalement during rebellions (rather than cases of robbery) like the Bosnian revolt of 1852, within the 1860s Macedonian times of trouble, during the Cretan insurrection 1866-69, and during the insurrections in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1876-77.

Tales and anecdotes concerning swift and harsh Ottoman justice for comparatively trivial offenses abound. Dimitrie Cantemir, a Moldavian noble living in Constantinople at the end of the 17th century, and often engaged in pleas of cases towards Ottoman authorities, narrates a tale from the building of a great mosque there in 1461. The Greek architect was amply rewarded by the sultan, so that a whole street was privileged to the Greek populace in recognition of his efforts. However, some asked the architect if he could even build a greater and more beautiful mosque than the one completed. Incautiously, the architect said sure enough, if I were given the materials. The sultan, upon hearing this, was so fearful that his successors might create an even more beautiful mosque than his own, that just in case, he chose to impale the architect to deprive successors of that genius, commemorating the event by erect a huge iron spike in the middle of the mosque. Not even bothering to refute this tale of impalement, Cantemir says that he does, however, believe in the grand gift of the street, because he had used the original charter from the sultan to protect the Greek interest when somebody wanted to deprive the Greeks of the privilege. Cantemir won his case. In 1632, under Murad IV (r.1623-40), a hapless interpreter in a fierce dispute between the French ambassador and Ottoman authorities was impaled alive for faithfully translating the insolent words of the ambassador. Furthermore, Murad IV sought to ban the use of tobacco, and reportedly impaled alive a man and a woman for breaking the law, the one for selling tobacco, the other for using it. Another such anecdote, illustrative of European ideas of "topsy-turvy" Oriental governments with scant respect for rank and "proper" ways for the people to address the powers of the State is said to have occurred in 1695 under Mustafa II: The Grand Vizier prevented access to the sultan to a poor shoemaker who had a petition for his sovereign. Once the sultan learnt of it, he promptly ordered the Grand Vizier to be impaled, although the Grand Vizier was the son of the sultan's favourite concubine.

Examples exist, though, of what might be called corruption of justice, in which local potentates like pashas at, for example, the instigation of one population group delivered severe penalties on another. For example, in 1762, there was a Franciscan monastery situated some distance from Gradiška, on the way to Banja Luka. The Greek Orthodox clergy convinced the local pasha to put pressure on the Franciscan monks that they should recognize the Patriarch at Constantinople as the head of the true, Christian faith. The monks refused to do so, and in consequence, the abbot was impaled, and the 26 other monks beheaded.

During the Ottoman rule of Greece, impalement became an important tool of psychological warfare, intended to put terror into the peasant population. By the 18th century, Greek bandits turned guerrilla insurgents (known as klephts) became an increasing annoyance to the Ottoman government. Captured klephts were often impaled, as were peasants that harbored or aided them. Victims were publicly impaled and placed at highly visible points, and had the intended effect on many villages who not only refused to help the klephts, but would even turn them in to the authorities. The Ottomans engaged in active campaigns to capture these insurgents in 1805 and 1806, and were able to enlist Greek villagers, eager to avoid the stake, in the hunt for their outlaw countrymen.

Impalement was, on occasion, aggravated with being set over a fire, the impaling stake acting as a spit, so that the impaled victim might be roasted alive. Among other severities, Ali Pasha, an Albanian-born Ottoman noble who ruled Ioannina, had rebels, criminals, and even the descendants of those who had wronged him or his family in the past, impaled and roasted alive. For example, Thomas Smart Hughes, visiting Greece and Albania in 1812–13, says the following about his stay in Ioannina:

"Here criminals have been roasted alive over a slow fire, impaled, and skinned alive; others have had their extremities chopped off, and some have been left to perish with the skin of the face stripped over their necks. At first I doubted the truth of these assertions, but they were abundantly confirmed to me by persons of undoubted veracity. Some of the most respectable inhabitants of loannina assured me that they had sometimes conversed with these wretched victims on the very stake, being prevented from yielding to their torturing requests for water by fear of a similar fate themselves. Our own resident, as he was once going into the serai of Litaritza, saw a Greek priest, the leader of a gang of robbers, nailed alive to the outer wall of the palace, in sight of the whole city."

During the Greek War of Independence (1821–1832), Athanasios Diakos, a klepht and later a rebel military commander, was captured after the Battle of Alamana (1821), near Thermopylae, and after refusing to convert to Islam and join the Ottoman army, he was impaled, and died after three days. Diakos became a martyr for a Greek independence and was later honored as a national hero.

One of the worst atrocities committed by the Greeks was the massacre following the Siege of Tripolitsa in October 1821, where several thousands were massacred, many impaled and roasted. To believe, however, that the massacre at Tripolitsa was the only, or the first atrocity committed by the Greeks would be wrong. Just two months earlier, in August 1821, for example, about the same time that some 40 Ionians were impaled by the Turks, Greek insurgents chose to roast a few Turks alive at Hydra William St Clair, in his "That Greece Might Still Be Free" warns against the skewed perception the Greek War of Independence received in Europe, and writes: "The Turkish atrocities against the Greek population were (...) witnessed with horror by many Europeans and soon were reported all over Europe. The initial atrocities in Greece, on the other hand, were seen by very few Europeans. If any were reported they were put down to justifiable hatred arising from extreme provocation, and explained away in the same terms as the occasional atrocities committed by European armies"

The "bamboo torture"

A recurring horror story on many websites and popular media outlets is that Japanese soldiers during World War II inflicted "bamboo torture" upon prisoners of war. The victim was supposedly tied securely in place above a young bamboo shoot. Over several days, the sharp, fast growing shoot would first puncture, then completely penetrate the victim's body, eventually emerging through the other side. The cast of the TV program MythBusters investigated bamboo torture in a 2008 episode and found that a bamboo shoot can penetrate through several inches of ballistic gelatin in three days. For research purposes, ballistic gelatin is considered comparable to human flesh, and the experiment thus supported the viability of this form of torture, if not its historicity. In her memoir "Hakka Soul", the Chinese poet and author Woon-Ping Chin mentions the "bamboo torture" as one of those tortures the locals believed the Japanese performed on prisoners.

This tale of using live trees impaling persons as they grow is, however, not confined to the context of WW2 and the Japanese as torturers, but was recorded in the 19th century as an allegation Malays used against the Siamese after the Siamese invasion of Kedah in 1821. Amongst other alleged punishments, the sprout of the nipah palm was used in the manner of a "bamboo torture". A "Madras civilian", in his travel description from 1820s India asserts that it is a well known punishment in Ceylon to use a bamboo shoot in this way.

Impalement in myth and art

Tales and myths of impalement

- Europe

The idea that the vampire "can only be slain with a stake driven through its heart" has been pervasive in European fiction. Examples such as Bram Stoker's Dracula and the more recent Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Twilight series' all incorporate that idea. In classic European folklore, it was believed that one method (among several) to "kill" a vampire, or prevent a corpse from rising as a vampire, was to drive a wooden stake through the heart before interment. In one story, an Istrian peasant named Jure Grando died and was buried in 1656. It was believed that he returned as a vampire, and at least one villager tried to drive a stake through his heart, but failed in the attempt. Finally, in 1672, the corpse was decapitated, and the vampire terror was put to rest. Although the Easten European, in particular Slavic (but also Roumanian), conception of the vampire as an undead creature in which impaling it was central to either destroying it, or at least immobilizing it, is the most well-known European tradition, such traditions can also be found elsewhere in Europe. In Greece, the troublesome undead were usually called a vrykolakas. The archaeologist Susan-Marie Cronkite describes an odd grave found at Mytilene, at Lesbos, a find the archeologists connected with the vrykolakas superstition:

"In the north side of the cemetery, however, we came across a surprising find – a grave unlike any other found within the cemetery. This burial contained the skeleton of a good sized, middle aged man buried in a well constructed grave dug into the preserved remains of the aforementioned Late Classical city fortification wall. An area of the interior of the wall had been removed, leaving a shallow, stone-lined crypt. The body was first placed within a wooden coffin the lid of which was attached along all four edges by many small, iron nails. This coffin was then placed in the crypt and the whole grave buried. Even more surprising, during excavation three 20cm (8 inch) long, curving iron spikes were found in with the body – one at the neck, one at groin level and one at the ankles. The alignment of the spikes suggested that they had been hammered into the coffin through the lid, ensuring the coffin would never be opened.

The Norse draugr, or haugbui (mound-dweller), was a type of undead typically (but not exclusively) associated with those put (supposedly) to rest in burial mounds/tumuli. The approved methods of killing a draugr are "to sever his head from his body and set the same beneath his rump, or impale his body with a stake or burn it to ashes". Dieter Furcht speculates that the impalement in the German live burial+impalement tradition was not so much to be regarded as an execution method on its own, but rather a way to prevent the condemned to become an avenging, undead Wiedergänger. But, as shown, examples exist that impalement was, indeed, also used as the direct execution method there.

Although in modern vampiric lore, the stake is regarded as a very effective tool against the undead, people in pre-modern Europe could have their doubts. Edward Payson Evans tells the following story, from the city Kadaň:

In 1337, a herdsman near the the town of Cadan came forth from his grave every night, visiting the villages, terrifying the inhabitants, conversing affably with some and murdering others. Every person, with whom he associated, was doomed to die within eight days and to wander as a vampire after death. In order to keep him in his grave, a stake was driven through his body, but he only laughed at this clumsy attempt to impale a ghost, saying: "You have really rendered me a great service by providing me with a staff, with which to ward off dogs when I go out to walk"

A graphic description of the vertical impalement of a Serbian rebel by Ottoman authorities can be found in Ivo Andrić's novel The Bridge on the Drina. Andrić was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for the whole of his literary contribution, though this novel was the magnum opus.

- Americas

In British Columbia, a folk tale from the Lillooet People is preserved in which impalement occurs as a central element. A man became suspicious of his wife because she went out each day to gather roots and cedar-bark but hardly ever brought anything home. One day, he spied on her, and discovered that she was cavorting with a lynx, rather than doing her wifely duties. The next day, he asked her to accompany her, and they went out in the forest, and came at last to a very tall tree. The man climbed to the top of it, the wife following. The jealous man then sharpened the top of the tree with his knife, and impaled his wife on it. On his way down, he removed the bark of the tree, so it became slick. The woman cried out her pain and her brothers heard her. They and animals they called to help them tried to rescue her, but the stem was too slick for them to climb up to reach her. Then a snail offered to help her, and slowly crawled up the tree. But alas, the snail moved too slowly, and by the time it took him to reach the top of the tree, the woman was dead.

Among tribes living around the Titicaca, tales circulated in the sixteenth century that prior to the Incas, a mysterious group of white men lived there, and their banishment was somehow connected with the birth of the Sun. A sixteenth century tale collected by a Spanish missionary tells of such an individual, called Tanupa or Taapac, who was impaled by other Indians around the Titicaca, and a shrine was set up there to commemorate the events.

- Indian sub-continent

In the Hindu Draupadi cult, impalement, of animals, demons and humans is a recurring motif within legends and symbolic re-enactments during holidays/festivals.