This is an old revision of this page, as edited by OsamaK (talk | contribs) at 06:13, 15 May 2013 (→Germany: link to Communist Party of Germany). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 06:13, 15 May 2013 by OsamaK (talk | contribs) (→Germany: link to Communist Party of Germany)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about freedom of speech in specific jurisdictions. For the concept itself, see Freedom of speech.Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with relatively authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms (see propaganda model) and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws even in countries seen as liberal democracies.

International law

Main article: Freedom of speech (international)The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, provides, in Article 19, that:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Technically, as a resolution of the United Nations General Assembly rather than a treaty, it is not legally binding in its entirety on members of the UN. Furthermore, whilst some of its provisions are considered to form part of customary international law, there is dispute as to which. Freedom of speech is granted unambiguous protection in international law by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which is binding on around 150 nations.

In adopting the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Monaco, Australia and the Netherlands insisted on reservations to Article 19 insofar as it might be held to affect their systems of regulating and licensing broadcasting.

African continent

The majority of African constitutions provide legal protection for freedom of speech. However, these rights are exercised inconsistently in practice. The replacement of authoritarian regimes in Kenya and Ghana has substantially improved the situation in those countries. On the other hand, Eritrea allows no independent media and uses draft evasion as a pretext to crack down on any dissent, spoken or otherwise. One of the poorest and smallest nations in Africa, Eritrea is now the largest prison for journalists; since 2001, fourteen journalists have been imprisoned in unknown places without a trial. Sudan, Libya, and Equatorial Guinea also have repressive laws and practices. In addition, many state radio stations (which are the primary source of news for illiterate people) are under tight control and programs, especially talk shows providing a forum to complain about the government, are often censored. Also countries like Somalia and Egypt provide legal protection for freedom of speech but it is not used publicly.

See also: Censorship in Algeria, Censorship in Tunisia.

South Africa

South Africa is probably the most liberal in granting freedom of speech, however in light of South Africa's racial and discriminatory history, particularly the Apartheid era, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996 precludes expression that is tantamount to the advocacy of hatred based on some listed grounds. Freedom of speech and expression are both protected and limited by a section in the South African Bill of Rights, chapter 2 of the Constitution. Section 16 makes the following provisions:

- § 16 Freedom of expression

- (1) Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes-

- (a) freedom of the press and other media;

- (b) freedom to receive or impart information or ideas;

- (c) freedom of artistic creativity; and

- (d) academic freedom and freedom of scientific research.

- (2) The right in subsection (1) does not extend to-

- (a) propaganda for war;

- (b) incitement of imminent violence; or

- (c) advocacy of hatred that is based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and that constitutes incitement to cause harm.

- (1) Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes-

In 2005, the South African Constitutional Court set an international precedent in the case of Laugh It Off Promotions CC v South African Breweries International when it found that the small culture jamming company Laugh-it-Off's right to freedom of expression outweighs the protection of trademark of the world's second largest brewery.

Sudan

Blasphemy against religion is illegal in Sudan under Blasphemy laws.

Asia

Several Asian countries provide formal legal guarantees of freedom of speech to their citizens. These are not, however, implemented in practice in some countries. Countries such as Myanmar, North Korea and some Central Asian Republics are reported to brutally repress freedom of speech. Freedom of speech has improved somewhat in the People's Republic of China in recent years, but the level of free expression is still far from that of Western nations. There is no clear correlation between legal and constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and actual practices among Asian nations.

Hong Kong

Under Hong Kong Basic Law,

- Hong Kong residents shall have freedom of speech.

- The freedom of the person of Hong Kong residents shall be inviolable.

- The freedom and privacy of communication of Hong Kong residents shall be protected by law.

India

Main article: Freedom of press in India See also: Censorship in IndiaThe Indian Constitution guarantees freedom of speech to every citizen and there have been landmark cases in the Indian Supreme Court that have affirmed the nation's policy of allowing free press and freedom of expression to every citizen. In India, citizens are free to criticize politics, politicians, bureaucracy and policies. The freedoms are comparable to those in the United States and Western European democracies. Article 19 of the Indian constitution states that:

All citizens shall have the right —

- to freedom of speech and expression;

- to assemble peaceably and without arms;

- to form associations or unions;

- to move freely throughout the territory of India;

- to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India; and

- to practise any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business.

These rights are limited so as not to effect:

- The integrity of India

- The security of the State

- Friendly relations with foreign States

- Public order

- Decency or morality

- Contempt of court

- Defamation or incitement to an offence

Freedom of speech is restricted by the National Security Act of 1980 and in the past, by the Prevention of Terrorism Ordinance (POTO) of 2001, the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) from 1985 to 1995, and similar measures. Freedom of speech is also restricted by Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 which deals with sedition and makes any speech or expression which brings contempt towards government punishable by imprisonment extending from three years to life. In 1962 the Supreme Court of India held this section to be constitutionally valid in the case Kedar Nath Singh vs State of Bihar.

Indonesia

Blasphemy against religion is illegal in Indonesia under blasphemy laws.

Iran

Blasphemy against Islam is illegal in Iran.

According to the Press Freedom Index for 2007, Iran ranked 166th out of 169 nations. Only three other countries - Eritrea, North Korea, and Turkmenistan - had more restrictions on news media freedom than Iran. The government of Ali Khamenei and the Supreme National Security Council imprisoned 50 journalists in 2007 and all but eliminated press freedom. Reporters Without Borders (RWB) has dubbed Iran the "Middle East's biggest prison for journalists."

Japan

Freedom of speech is guaranteed by article 21 of the Japanese constitution. There are few exemptions to this right and a very broad spectrum of opinion is tolerated by the media and authorities.

Malaysia

See also: Censorship in MalaysiaIn Malaysia, "God" and "Prophet Muhammad" are used by politicians to answer to the peoples and the media. In May 2008, the Prime Minister of Malaysia Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi put forward a headline "Media should practice voluntary self-censorship", saying there is no such thing as unlimited freedom and the media should not be abashed of "voluntary self-censorship" to respect cultural norms, different societies hold different values and while it might be acceptable in secular countries to depict a caricature of Prophet Muhammad, it was clearly not the case here. "It is not a moral or media sin to respect prophets". He said the Government also wanted the media not to undermine racial and religious harmony to the extent that it could threaten national security and public order. "I do not see these laws as curbs on freedom. Rather, they are essential for a healthy society."

Pakistan

Articles 19 of the Constitution of Pakistan guarantees freedom of speech and expression, and freedom of the press with certain restrictions. Blasphemy against Islam is illegal in Pakistan.

People's Republic of China (mainland)

See also: Censorship in the People's Republic of ChinaArticle 35 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China claims that:

Citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration.

Nonetheless strict censorship is widespread in mainland China. There is heavy government involvement in the media, with many of the largest media organizations being run by the Communist-Party-led government. References to democracy, the free Tibet movement, Taiwan as an independent country, the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the Arab Spring, certain religious organizations and anything questioning the legitimacy of the Communist Party of China are banned from use in public and blocked on the Internet. Web portals including Microsoft's MSN have come under criticism for aiding in these practices, including banning the word "democracy" from its chat-rooms in China.

Due to close geographical proximity to Hong Kong, parts of southern China are able to receive broadcast signals from television channels in Hong Kong, where China's censorship does not apply. However, comments that the Communist Party feel uncomfortable with are cut out and replaced with TV commercials before they can reach consumers TVs in mainland China. Very few Western films are given permission to play in Chinese theatres, although widespread unlicensed copying of these films makes them widely available.

Philippines

Article III Section 4 of the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines specifies that no law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech or of expression. Some laws inconsistent with a broad application of this mandate are in force, however.

Saudi Arabia

Blasphemy against Islam is illegal in Saudi Arabia.

South Korea

The South Korean constitution guarantees freedom of speech, press, petition and assembly. However, behaviors or speeches in favor of the North Korean regime or communism can be punished by the National Security Law, though in recent years prosecutions under this law have been rare.

There is a strict election law that takes effect a few months before elections which prohibits most speech that either supports or criticizes a particular candidate or party. One can be prosecuted for political parodies and even for wearing a particular color (usually the color of a party).

The UN Human Rights Commission expressed concerns about South Korea's deterioration of online free speech.

Thailand

See also: Censorship in Thailand and Internet censorship in ThailandWhile the Thai constitution provides for freedom of expression, by law the government may restrict freedom of expression to preserve national security, maintain public order, preserve the rights of others, protect public morals, and prevent insults to Buddhism. The lese-majeste law makes it a crime, punishable by up to 15 years' imprisonment for each offense, to criticize, insult, or threaten the king, queen, royal heir apparent, or regent. Defamation is a criminal offense and parties that criticize the government or related businesses may be sued, setting the stage for self-censorship.

Censorship expanded considerably starting in 2003 during the Thaksin Shinawatra administration and after the 2006 military coup. Prosecutions for lese-majeste offenses increased significantly starting in 2006. Journalists are generally free to comment on government activities and institutions without fear of official reprisal, but they occasionally practice self-censorship, particularly with regard to the monarchy and national security. Broadcast media are subject to government censorship, both directly and indirectly, and self-censorship is evident. Under the Emergency Decree in the three southernmost provinces, the government may restrict print and broadcast media, online news, and social media networks there.

Thailand practices selective Internet filtering in the political, social, and Internet tools areas, with no evidence of filtering in the conflict/security area in 2011. Thailand is on Reporters Without Borders list of countries under surveillance in 2011 and is listed as "Not Free" in the Freedom on the Net 2011 report by Freedom House, which cites substantial political censorship and the arrest of bloggers and other online users.

Australia

See also: Censorship in AustraliaAustralia does not have explicit freedom of speech in any constitutional or statutory declaration of rights, with the exception of political speech which is protected from criminal prosecution at common law per Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth.

In 1992 the High Court of Australia judged in the case of Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth that the Australian Constitution, by providing for a system of representative and responsible government, implied the protection of political communication as an essential element of that system. This freedom of political communication is not a broad freedom of speech as in other countries, but rather a freedom whose purpose is only to protect political free speech. This freedom of political free speech is a shield against government prosecution, not a shield against private prosecution (civil law). It is also less a causal mechanism in itself, rather than simply a boundary which can be adjudged to be breached. Despite the court's ruling, however, not all political speech appears to be protected in Australia and several laws criminalise forms of speech that would be protected in other democratic countries such as the United States.

In 1996, Albert Langer was imprisoned for advocating that voters fill out their ballot papers in a way that was invalid. Amnesty International declared Langer to be a prisoner of conscience. The section which outlawed Langer from encouraging people to vote this way has since been repealed and the law now says only that it is an offence to print or publish material which may deceive or mislead a voter.

The Howard Government re-introduced sedition law, which criminalises some forms of expression. Media Watch ran a series on the amendments on ABC television.

In 2006, CSIRO senior scientist Graeme Pearman was reprimanded and encouraged to resign after he spoke out on global warming. The Howard Government was accused of limiting the speech of Pearman and other scientists.

Europe

Council of Europe

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), signed on 4 November 1950, guarantees a broad range of human rights to inhabitants of member countries of the Council of Europe, which includes almost all European nations. These rights include Article 10, which entitles all citizens to free expression. Echoing the language of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights this provides that:

- Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

The Convention established the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Any person who feels his or her rights have been violated under the Convention by a state party can take a case to the Court. Judgements finding violations are binding on the States concerned and they are obliged to execute them. The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe monitors the execution of judgements, particularly to ensure payment of the amounts awarded by the Court to the applicants in compensation for the damage they have sustained.

The Convention also includes some other restrictions:

- The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or the rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

For example, the Council of Europe Explanatory Report of the Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime states the "European Court of Human Rights has made it clear that the denial or revision of 'clearly established historical facts – such as the Holocaust – would be removed from the protection of Article 10 by Article 17' of the ECHR" in the Lehideux and Isorni v. France judgment of 23 September 1998.

Each party to the Convention must alter its laws and policies to conform with the Convention. Some, such as Ireland or the United Kingdom, have expressly incorporated the Convention into their domestic laws. The guardian of the Convention is the European Court of Human Rights. This court has heard many cases relating to freedom of speech, including cases that have tested the professional obligations of confidentiality of journalists and lawyers, and the application of defamation law, a recent example being the so-called "McLibel case".

European Union

Currently, all members of the European Union are signatories of the European Convention on Human Rights in addition to having various constitutional and legal rights to freedom of expression at the national level. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union has been legally binding since December 1, 2009 when the Treaty of Lisbon became fully ratified and effective. Article 11 of the Charter, in part mirroring the language of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights, provides that

- 1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers.

- 2. The freedom and pluralism of the media shall be respected.

The European Court of Justice takes into account both the Charter and the Convention when making its rulings. According to the Treaty of Lisbon, the European Union accedes to the European Convention as an entity in its own right, making the Convention binding not only on the governments of the member states but also on the supranational institutions of the EU.

Czech Republic

Freedom of speech in the Czech Republic is guaranteed by the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms, which has the same legal standing as the Czech Constitution. It is the first freedom of the charter's second division - political rights. It reads as follows:

- Article 17

- (1) The freedom of expression and the right to information are guaranteed.

- (2) Everyone has the right to express their opinion in speech, in writing, in the press, in pictures, or in any other form, as well as freely to seek, receive, and disseminate ideas and information irrespective of the frontiers of the State.

- (3) Censorship is not permitted.

- (4) The freedom of expression and the right to seek and disseminate information may be limited by law in the case of measures necessary in a democratic society for protecting the rights and freedoms of others, the security of the State, public security, public health, and morals.

- (5) State bodies and territorial self-governing bodies are obliged, in an appropriate manner, to provide information on their activities. Conditions therefore and the implementation thereof shall be provided for by law.

Specific limitations of the freedom of speech within the meaning of Article 17(4) may be found in the Criminal Code as well in other enactments. These include the prohibition of:

- unauthorized handling of personal information (Article 180 of the Criminal Code), which protects the right to privacy,

- defamation (Article 184 of the Criminal Code),

- dissemination of pornography depicting disrespect to a human, abuse of an animal, or dissemination of any pornography to children (Article 191 of the Criminal Code),

- seducing to use or propagation of use of addictive substances other than alcohol (Article 287 of the Criminal Code), which protects public health,

- denigration of a nation, race, ethnic or other group of people (Article 355 of the Criminal Code), i.e. hate speech,

- inciting of hatred towards a group of people or inciting limitation of their civil rights (Article 356 of the Criminal Code),

- spreading of scaremongering information (Article 357 of the Criminal Code), e.g. fake bomb alerts,

- public incitement of perpetration of a crime (Article 364 of the Criminal Code),

- public approval of a felony crime (Article 365 of the Criminal Code),

- public display of sympathy towards a movement oriented at curbing rights of the people (Article 404 of the Criminal Code), e.g. propagation of hate-groups,

- public denial, questioning, endorsement or vindication of genocide (Article 405 of the Criminal Code), e.g. Auschwitz lie,

- incitement of an offensive war (Article 407 of the Criminal Code).

Most of the limitations of the free speech in the Czech Republic aim at protection of rights of individuals or minority groups. Unlike in some other European countries there are no limits on speech criticizing or denigrating government, public officials or state symbols.

Denmark

See also: Censorship in DenmarkFreedom of speech in Denmark is granted by Grundloven:

- § 77 Any person shall be at liberty to publish his ideas in print, in writing, and in speech, subject to his being held responsible in a court of law. Censorship and other preventive measures shall never again be introduced.

Hate speech is illegal according to the Danish Penal Code § 266(b):

- Any person who, publicly or with the intention of disseminating ... makes a statement ... threatening (trues), insulting (forhånes), or degrading (nedværdiges) a group of persons on account of their race, national or ethnic origin or belief shall be liable to a fine or to simple detention or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years.

The 1991 Media Liability Act (Medieansvarsloven) creates criminal and civil mandates that mass media content and conduct must be consistent with journalism ethics and the right of reply, and also created the Press Council of Denmark (Pressenævnet) which can impose fines and imprisonment up to 4 months.

France

See also: Censorship in France and Hate speech laws in France| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, of constitutional value, states, in its article 11:

- The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, save to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

In addition, France adheres to the European Convention on Human Rights and accepts the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights.

The Press Law of 1881, as amended, guarantees freedom of the press, subject to several exceptions. The Pleven Act of 1972 (after Justice Minister René Pleven) prohibits incitement to hatred, discrimination, slander and racial insults. The Gayssot Act of 1990 prohibits any racist, anti-Semite, or xenophobic activities, including Holocaust denial. The Law of 30 December 2004 prohibits hatred against people because of their gender, sexual orientation, or disability.

An addition to the Public Health Code was passed on the 31 December 1970, which punishes the "positive presentation of drugs" and the "incitement to their consumption" with up to five years in prison and fines up to €76,000. Newspapers such as Libération, Charlie Hebdo and associations, political parties, and various publications criticizing the current drug laws and advocating drug reform in France have been repeatedly hit with heavy fines based on this law.

France does not implement any preliminary government censorship for written publications. Any violation of law must be processed through the courts.

The government has a commission recommending movie classifications, the decisions of which can be appealed before the courts. Another commission oversees publications for the youth. The Minister of the Interior can prohibit the sale of pornographic publications to minors, and can also prevent such publications from being publicly displayed or advertised; such decisions can be challenged before administrative courts.

The government restricts the right of broadcasting to authorized radio and television channels; the authorizations are granted by an independent administrative authority; this authority has recently removed the broadcasting authorizations of some foreign channels because of their antisemitic content.

As part of "internal security" enactments passed in 2003, it is an offense to insult the national flag or anthem, with a penalty of a maximum 9,000 euro fine or up to six months' imprisonment. Restrictions on "offending the dignity of the republic", on the other hand, include "insulting" anyone who serves the public (potentially magistrates, police, firefighters, teachers and even bus conductors). The legislation reflects the debate that raged after incidents such as the booing of the "La Marseillaise" at a France vs. Algeria football match in 2002.

Germany

See also: Censorship in GermanyFreedom of expression is granted by Article 5 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, which also states that there is no censorship and freedom of expression may be limited by law.

The press is regulated by the law of Germany as well as all 16 States of Germany. The most important and sometimes controversial regulations limiting speech and the press can be found in the Criminal code:

- Insult is punishable under Section 185. Satire and similar forms of art enjoy more freedom but have to respect human dignity (Article 1 of the Basic law).

- Malicious Gossip and Defamation (Section 186 and 187). Utterances about facts (opposed to personal judgement) are allowed if they are true and can be proven. Yet journalists are free to investigate without evidence because they are justified by Safeguarding Legitimate Interests (Section 193).

- Hate speech may be punishable if against segments of the population and in a manner that is capable of disturbing the public peace (Section 130 ), including racist agitation and antisemitism.

- Holocaust denial is punishable according to Section 130 subsection 3.

- Membership in or support of banned political parties (Section 86). Currently the only banned party is the Nazi Party, but historically all non-Nazi parties have been banned (1933–1945), as well as the Communist Party (1933–1945, 1956–1968).

- Dissemination of Means of Propaganda of Unconstitutional Organizations (Section 86).

- Use of Symbols of Unconstitutional Organizations (Section 86a). Items such as the Swastika, but also the hammer and sickle when the Communist Party is banned.

- Disparagement of

- the Federal President (Section 90).

- the State and its Symbols (Section 90a).

- Insult to Organs and Representatives of Foreign States (Section 103).

- Rewarding and Approving Crimes (Section 140).

- Casting False Suspicion (Section 164).

- Insulting of Faiths, Religious Societies and Organizations Dedicated to a Philosophy of Life if they could disturb public peace (Section 166).

- Dissemination of Pornographic Writings (Section 184).

Outdoor assemblies must be registered beforehand. Assemblies at memorial sites are banned. Individuals and groups may be banned from assembling, especially those whose fundamental rights have been revoked and banned political parties. The Love Parade decision (1 BvQ 28/01 and 1 BvQ 30/01 of 12 July 2001) determined that for an assembly to be protected it must comply with the concept of a constituent assembly, or the so-called narrow concept of assembly whereby the participants in the assembly must pursue a common purpose that is in the common interest.

Greece

The 14th article of the Constitution of Greece makes it an offence for the press to insult the President of Greece as well as Christianity and any other religion recognized by the state.

Hungary

Articles VII, VIII, IX, and X of the Fundamental Law of Hungary establishes the rights of freedom of expression, speech, press, thought, conscience, religion, artistic creation, scientific research, and assembly. Some of these rights are limited by the penal code:

- Section 269 - Incitement against a community

- A person who incites to hatred before the general public against

- a) the Hungarian nation,

- b) any national, ethnic, racial group or certain groups of the population,

- shall be punishable for a felony offense with imprisonment up to three years.

This list has been updated to include: "people with disabilities, various sexual identity and sexual orientation", effective from July 2013.

It is also illegal under Section 269/C of the penal code and punishable with three years of imprisonment, to publicly "deny, question, mark as insignificant, attempt to justify the genocides carried out by the National Socialist and Communist regimes, as well as the facts of other crimes against humanity."

Ireland

See also: Censorship in the Republic of IrelandFreedom of speech is protected by Article 40.6.1 of the Irish constitution. However the article qualifies this right, providing that it may not be used to undermine "public order or morality or the authority of the State". Furthermore, the constitution explicitly requires that the publication of "blasphemous, seditious, or indecent matter" be a criminal offence, leading the government to pass a new blasphemy law on 8 July 2009.

The scope of the protection afforded by this Article has been interpreted restrictively by the judiciary, largely as a result of the wording of the Article, which qualifies the right before articulating it. Indeed, until an authoritative pronouncement on the issue by the Supreme Court, many believed that the protection was restricted to "convictions and opinions" and, as a result, a separate right to communicate was, by necessity, implied into Article 40.3.2. This judicial conservatism is at variance with the concept of speech as a democratic imperative. This, albeit trite, justification for free speech has underpinned the liberal, progressive interpretation of the First Amendment by the United States Supreme Court.

Under the European Convention on Human Rights Act 2003, all of the rights afforded by the European Convention serve as a guideline for the judiciary to act upon. The act is subordinate to the constitution.

Italy

Vilication of religion is illegal in Italy under Section 403 of the Criminal code; Defamation is illegal under section 595; Insult is illegal under Section 594; Disparagement of the President of State is illegal under Section 278.

Malta

Blasphemy against the Roman Catholic church is illegal in Malta.

The Netherlands

Article 7 of the Dutch Grondwet in its first paragraph grants everybody the right to make public ideas and feelings by printing them without prior censorship, but not exonerating the author from his liabilities under the law. The second paragraph says that radio and television will be regulated by law but that there will be no prior censorship dealing with the content of broadcasts. The third paragraph grants a similar freedom of speech as in the first for other means of making ideas and feelings public but allowing censorship for reasons of decency when the public that has access may be younger than sixteen years of age. The fourth and last paragraph exempts commercial advertising from the freedoms granted in the first three paragraphs.

The penal code has laws however sanctioning certain types of expression. Such laws and freedom of speech are at the centre of a public debate in The Netherlands after the arrest on 16 May 2008 of cartoonist Gregorius Nekschot. Jurisprudence from the 1960s prohibits prosecution of blasphemy. Parliament has recently expressed its wish to abolish the law penalizing blasphemy. The current Christian Democrat Justice Minister would however prefer to renew it and expand it to include non-religious philosophies of life, thus making it possible to anticipate and prevent international outcry similar to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy. Laws that punish discriminatory speech also exist and are being used against Gregorius Nekschot. Laws on lèse majesté exist and are occasionally used to prosecute.

The Dutch Criminal Code § 137(c) criminalizes:

- … deliberately giv public expression to views insulting to a group of persons on account of their race, religion, or conviction or sexual preference.

Poland

"Statutes of Wiślica" introduced in 1347 by Casimir III of Poland codified freedom of speech in medieval Poland e.g. book publishers were not to be persecuted. The Constitution of the Republic of Poland, specifically forbids, the existence of "political parties and other organizations whose programmes are based upon totalitarian methods and the modes of activity of nazism, fascism and communism, as well as those whose programmes or activities sanction racial or national hatred, the application of violence for the purpose of obtaining power or to influence the State policy, or provide for the secrecy of their own structure or membership". As of 2005, people are sometimes convicted and/or detained for about one day for insults to religious feeling (of the Roman Catholic Church) or to heads of state who are not yet, but soon will be, on Polish territory. On 18 July 2003, During 26–27 January 2005, about 30 human rights activists were temporarily detained by the police, allegedly for insulting Vladimir Putin, a visiting head of state. The activists were released after about 30 hours and only one was actually charged with insulting a foreign head of state.

Sweden

See also: Censorship in SwedenFreedom of speech is regulated in three parts of the Constitution of Sweden.

- Regeringsformen, Chapter 2 (Fundamental Rights and Freedoms) protects personal freedom of expression "whether orally, pictorially, in writing, or in any other way".

- Tryckfrihetsförordningen (Freedom of the Press Act) protects the freedom of printed press, as well as the principle of free access to public records (offentlighetsprincipen) and the right to communicate information to the press anonymously. For a newspaper to be covered by this law, it must be registered and have a "responsible editor".

- Yttrandefrihetsgrundlagen (Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression) extends protections similar to those of Tryckfrihetsförordningen to other media, including television, radio and web sites.

Hate speech laws prohibit threats or expressions of contempt based on race, skin colour, nationality or ethnic origin, religious belief or sexual orientation. Some notable recent cases are Radio Islam and Åke Green.

United Kingdom

See also: Censorship in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom citizens have a negative right to freedom of expression under the common law. In 1998, the United Kingdom incorporated the European Convention, and the guarantee of freedom of expression it contains in Article 10, into its domestic law under the Human Rights Act. However there is a broad sweep of exceptions including threatening, abusive or insulting words or behavior intending or likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress or cause a breach of the peace (which has been used to prohibit racist speech targeted at individuals), sending another any article which is indecent or grossly offensive with an intent to cause distress or anxiety, incitement, incitement to racial hatred, incitement to religious hatred, incitement to terrorism including encouragement of terrorism and dissemination of terrorist publications, glorifying terrorism, collection or possession of a document or record containing information likely to be of use to a terrorist, treason including imagining the death of the monarch, sedition, obscenity, indecency including corruption of public morals and outraging public decency, defamation, prior restraint, restrictions on court reporting including names of victims and evidence and prejudicing or interfering with court proceedings, prohibition of post-trial interviews with jurors, scandalising the court by criticising or murmuring judges, time, manner, and place restrictions, harassment, privileged communications, trade secrets, classified material, copyright, patents, military conduct, and limitations on commercial speech such as advertising.

UK laws on defamation are among the strictest in the western world, imposing a high burden of proof on the defendant. However, the Education (No. 2) Act 1986 guarantees freedom of speech (within institutions of further education and institutions of higher education) as long as it is within the law (see section 43 at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/61). UK defamation law may have recently experienced a considerable liberalising effect as a result of the ruling in Jameel v Wall Street Journal in October 2006. A ruling of the House of Lords—the then highest court of appeal—revived the so-called Reynolds Defence, in which journalism undertaken in the public interest shall enjoy a complete defence against a libel suit. Conditions for the defence include the right of reply for potential claimants, and that the balance of the piece was fair in view of what the writer knew at the time. The ruling removed the awkward—and hitherto binding—conditions of being able to describe the publisher as being under a duty to publish the material and the public as having a definite interest in receiving it. The original House of Lords judgment in Reynolds was unclear and held 3–2; whereas Jameel was unanimous and resounding. Lord Hoffman's words, in particular, for how the judge at first instance had applied Reynolds so narrowly, were very harsh. Hoffman LJ made seven references to Eady J, none of them favorable. He twice described his thinking as unrealistic and compared his language to "the jargon of the old Soviet Union."

The Video Recordings Act 2010 requires most video recordings and some video games offered for sale in the United Kingdom to display a classification supplied by the BBFC. There are no set regulations as to what cannot be depicted in order to gain a classification as each scene is considered in the context of the wider intentions of the work; however images that could aid, encourage, or are a result of the committing of a crime, along with sustained and graphic images of torture or sexual abuse are the most likely to be refused. The objectionable material may be cut by the distributor in order to receive a classification, but with some works it may be deemed that no amount of cuts would be able to make the work suitable for classification, effectively banning that title from sale in the country. Recordings refused a classification by the BBFC may still be shown in cinemas providing the local authority, from which a cinema must have a licence to operate, will permit them.

Norway

Article 100 of the Norwegian Constitution has granted freedom of speech since 1814 and is mostly unchanged since then. Article 142 of the penal code is a law against blasphemy, but no one has been charged since 1933, though it was upheld as late as 2004. Article 135a of the penal code is a law against hate speech, which is debated and not widely used.

Article 100 in the Constitution states:

- There shall be freedom of expression.

- No person may be held liable in law for having imparted or received information, ideas or messages unless this can be justified in relation to the grounds for freedom of expression, which are the seeking of truth, the promotion of democracy and the individual's freedom to form opinions. Such legal liability shall be prescribed by law.

- Everyone shall be free to speak his mind frankly on the administration of the State and on any other subject whatsoever. Clearly defined limitations to this right may only be imposed when particularly weighty considerations so justify in relation to the grounds for freedom of expression.

- Prior censorship and other preventive measures may not be applied unless so required in order to protect children and young persons from the harmful influence of moving pictures. Censorship of letters may only be imposed in institutions.

- Everyone has a right of access to documents of the State and municipal administration and a right to follow the proceedings of the courts and democratically elected bodies. Limitations to this right may be prescribed by law to protect the privacy of the individual or for other weighty reasons.

- It is the responsibility of the authorities of the State to create conditions that facilitate open and enlightened public discourse.

Switzerland

The Swiss Constitution also guarantees Freedom of speech and Freedom of information for every citizen (Article 16). But still the country makes some controversial decisions, which both Human Right Organizations and other states criticizes. The Swiss Animal Right organization "Verein gegen Tierfabriken Schweiz" took the country to the European Court of Human Rights twice for censoring a TV-Advertisement of the organization, in which the livestock farming of pigs is shown. The organization won both lawsuits, and the Swiss state was convicted to pay compensations. Another very controversial law of Switzerland is that persons who refuse to recognize the Armenian Genocide of 1915 have to face trial. The Turkish politician Doğu Perinçek was fined CHF 12,000 for denying the existence of the Genocide in 2007. Switzerland was criticized by Turkish media and Turkish politicians for acting against the freedom of opinion. Perinçek's application for a revision was rejected by the court. Holocaust denial is also illegal.

Turkey

See also: Censorship in TurkeyArticle 26 of the Constitution of Turkey guarantees the right to "Freedom of Expression and Dissemination of Thought". Moreover, the Republic of Turkey is a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights and submits to the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. The constitutional freedom of expression may be limited by provisions in other laws, such as Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, which outlaws denigration of the Turkish Nation, while also providing that "expression of thought intended to criticize shall not constitute a crime".

North America

Cuba

Main article: Censorship in CubaBooks, newspapers, radio channels, television channels, movies and music are censored. Cuba is one of the world's worst offenders of free speech according to the Press Freedom Index 2008. RWB states that Cuba is "the second biggest prison in the world for journalists" after the People's Republic of China.

Canada

Further information: History of free speech in Canada and Censorship in CanadaFreedom of expression in Canada is guaranteed by section 2(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms:

- 2. Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms: ... (b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication

Section 1 of the Charter, the so-called limitations clause, establishes that the guarantee of freedom of expression and other rights under the Charter are not absolute and can be limited under certain situations:

- The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. (emphasis added)

This section is double-edged. First it implies that a limitation on freedom of speech prescribed in law can be permitted, if it can be justified as being a reasonable limit in a free and democratic society. Conversely, it implies that a restriction can be invalidated, if it cannot be shown to be a reasonable limit in a free and democratic society.

Other laws that protect freedom of speech in Canada, and did so, to a limited extent, before the Charter was enacted in 1982, include the Implied Bill of Rights and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

In the landmark Supreme Court of Canada case R. v. Zundel (1992), the court struck down a provision in the Criminal Code of Canada that prohibited publication of false information or news, stating that it violated section 2(b) of the Charter.

Under section 318 of the Criminal Code of Canada, it is illegal to promote genocide. Under section 319, it is illegal to publicly incite hatred against people based on their colour, race, religion, ethnic origin, and sexual orientation, except where the statements made are true or are made in good faith. The prohibition against inciting hatred based on sexual orientation was added to the section in 2004 with the passage of Bill C-250. A prohibition against inciting hatred based on "gender identity" is slated to be included in section 318 with the passage of Bill C-279, once it has been given Royal Assent.

Canada has had a string of high-profile court cases in which writers and publishers have been prosecuted for their writings, in both magazines and web postings:

- In February 2006, Calgary Muslim leader Syed Soharwardy filed a human rights complaint against Western Standard publisher Ezra Levant. Levant was compelled to appear before the Alberta Human Rights Commission to discuss his intention in publishing the Muhammad cartoons. Levant posted a video of the hearing on YouTube. Levant questioned the competence of the Commission to take up the issue, and challenged it to convict him, "and sentence me to the apology", stating that he would then take "this junk into the real courts, where eight hundred years of common law" would come to his aid. In February 2008, Soharwardy dropped the complaint noting that "most Canadians see this as an issue of freedom of speech, that that principle is sacred and holy in our society."

- In May 2006, the Edmonton Council of Muslim Communities filed another Human Rights complaint against the Western Standard over the publishing of the cartoons. In August 2008, the Alberta Human Rights and Citizenship (AHRC) Commission dismissed the complaint, stating that, “given the full context of the republication of the cartoons, the very strong language defining hatred and contempt in the case law as well as consideration of the importance of freedom of speech and the ‘admonition to balance,’ the southern director concludes that there is no reasonable basis in the information for this complaint to proceed to a panel hearing.”

- In 2007, a complaint was filed with the Ontario Human Rights Commission related to an article "The Future Belongs to Islam," written by Mark Steyn, published in Maclean's magazine. The complainants alleged that the article and Maclean's refusal to provide space for a rebuttal violated their human rights. The complainants also claimed that the article was one of twenty-two Maclean's articles, many written by Steyn, about Muslims. Further complaints were filed with the Canadian Human Rights Commission and the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal. The Canadian Human Rights Commission dismissed the complaint in June 2008.

- A Montreal neo-Nazi, Jean-Sebastien Presseault, received a six-month prison sentence for willfully promoting hatred toward blacks and Jews on his website. Calling Presseault's opinions "vile" and "nauseating," Quebec Court Judge Martin Vauclair sent the heavily tattooed man back to jail. The 24 tattoos, including several Ku Klux Klan and Nazi symbols covering the defendant's torso, figure prominently in Vauclair's decision to give jail time, as opposed to a sentence to be served in the community, as the defence had hoped. "The violence he inflicted on his own body to leave almost-indelible marks of his convictions testify as to his unresolved frustrations but also to his deep-seated racist and hateful beliefs," Vauclair said.

- In February of 2010, Bill Whatcott had the Saskatchewan Human Rights Tribunal ruling against him alleging discrimination against four homosexuals and fining him $17,500 overturned by the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal. Part of the judgment acquitting Whatcott read, "the manner in which children in the public school system are to be exposed to messages about different forms of sexuality and sexual identity is inherently controversial. It must always be open to public debate. That debate will sometimes be polemical and impolite." The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which decided to hear the case. In February 2013, the Court decided that, although Bible passages, biblical beliefs and the principles derived from those beliefs can be legally and reasonably advanced in public discourse, extreme manifestations of the emotion described by the words "detestation" and "vilification" cannot be.

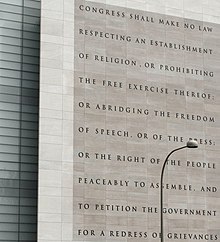

United States

Main article: Freedom of speech in the United States See also: Censorship in the United StatesIn the United States freedom of expression is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. There are several common law exceptions including obscenity, defamation, incitement, incitement to riot or imminent lawless action, fighting words, fraud, speech covered by government granted monopoly (copyright), and speech integral to criminal conduct. There are federal criminal law statutory prohibitions covering all the common law exceptions other than defamation, of which there is civil law liability, as well as terrorist threats, making false statements in "matters within the jurisdiction" of the federal government, speech related to information decreed to be related to national security such as military and classified information, false advertising, perjury, privileged communications, trade secrets, copyright, and patents. Most states and localities have many identical restrictions, as well as harassment, and time, place and manner restrictions. In addition, in California it is illegal to post a public official’s address or telephone number on the Internet.

Historically, local communities and governments have sometimes sought to place limits upon speech that was deemed subversive or unpopular. There was a significant struggle for the right to free speech on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley in the 1960s. And, in the period from 1906 to 1916, the Industrial Workers of the World, a working class union, found it necessary to engage in free speech fights intended to secure the right of union organizers to speak freely to wage workers. These free speech campaigns were sometimes quite successful, although participants often put themselves at great risk.

Freedom of speech is also sometimes limited to free speech zones, which can take the form of a wire fence enclosure, barricades, or an alternative venue designed to segregate speakers according to the content of their message. There is much controversy surrounding the creation of these areas — the mere existence of such zones is offensive to some people, who maintain that the First Amendment to the United States Constitution makes the entire country an unrestricted free speech zone. Civil liberties advocates claim that Free Speech Zones are used as a form of censorship and public relations management to conceal the existence of popular opposition from the mass public and elected officials.

Neither the federal nor state governments engage in preliminary censorship of movies. However, the Motion Picture Association of America has a rating system, and movies not rated by the MPAA cannot expect anything but a very limited release in theatres. Since the organization is private, no recourse to the courts is available. The rules implemented by the MPAA are more restrictive than the ones implemented by most First World countries. However, unlike comparable public or private institutions in other countries, the MPAA does not have the power to limit the retail sale of movies in tape or disc form based on their content, nor does it affect movie distribution in public (i.e., government-funded) libraries. Since 2000, it has become quite common for movie studios to release "unrated" DVD versions of films with MPAA-censored content put back in.

Unlike what has been called a strong international consensus that hate speech needs to be prohibited by law and that such prohibitions override, or are irrelevant to, guarantees of freedom of expression, the United States is perhaps unique among the developed world in that under law, hate speech is legal.

For instance, in July 2012 a US court ruled that advertisements with the slogan, "In any war between the civilized man and the savage, support the civilized man. Support Israel Defeat Jihad", are constitutionally protected speech and the government must allow their display in New York subways. In response on 27 September 2012 New York's Metropolitan Transportation Authority approved new guidelines for subway advertisements, prohibiting those that it “reasonably foresees would imminently incite or provoke violence or other immediate breach of the peace.” The MTA believes the new guidelines adhere to the court’s ruling and will withstand any potential First Amendment challenge. Under the new policy, the authority will continue to allow so-called viewpoint ads, but will require a disclaimer on each ad noting that it does not imply the authority’s endorsement of its views.

South America

Brazil

In Brazil, freedom of expression is a Constitutional right. Article Five of the Constitution of Brazil establishes that the expression of thought is free, anonymity being forbidden. Furthermore, the expression of intellectual, artistic, scientific, and communications activities is free, independently of censorship or license. However, there are legal provisions criminalizing the desecration of religious artifacts at the time of worship, hate speech, racism, defamation, calumny and libel. Brazilian Law also forbids "unjust and grave threats".

Historically, freedom of speech has been a right in Brazilian Law since the 1824 Constitution was enacted, though it was banned by the Vargas dictatorship and severely restricted under the military dictatorship in 1964–85.

Ecuador

Accusations or insults without factual basis can be punished by three months to three years in prison according to Article 494 of Ecuador's penal code. It is usually interpreted in media as criminal defamation and/or libel.

In 2012 the Supreme Court of Ecuador upheld a three-year prison sentence and a $42 million fine for criminal libel against an editor and the directors of the newspaper El Universo. In 2013 Assemblyman Cléver Jiménez was sentenced to a year in prison for criminal libel.

See also

- Free Speech Movement

- Freedom (political)

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange

- Media transparency

- Linguistic rights

- List of linguistic rights in African constitutions

- List of linguistic rights in European constitutions

References

- General Assembly of the United Nations (1948-12-10). "Universal Declaration of Human Rights" (pdf) (in English/French). pp. 4–5. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. "List of Declarations and Reservations to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights". Archived from the original on 2007-01-22. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- "Freedom of Expression". pre-1997. Archived from the original (doc) on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Laugh It Off Promotions CC v South African Breweries International (Finance) BV t/a SabMark International (Freedom of Expression Institute as Amicus Curiae) 2006 (1) SA 144 (CC) http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2005/7.html

- Terri Judy (2007-11-27). "Teacher held for teddy bear 'blasphemy'". London: The Independent.

- "Article 27". Basic Law Full Text. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- "Article 28". Basic Law Full Text. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- "Article 20". Basic Law Full Text. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ "19. Protection of certain rights regarding freedom of speech, etc" (doc). The Constitution of India. 1949-11-26. p. 8. Retrieved 2007-05-06. Cite error: The named reference "Title19" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- "Section 124A - Sedition", Indian Penal Code, 1860, VakilNo1.com

- Kedar Nath Singh vs State Of Bihar on 20 January, 1962, 1962 AIR 955, 1962 SCR Supl. (2) 769, indiankanoon.org

- "Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom May 2009" (PDF). Indonesia. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- "Iran Report" (PDF). Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom 2009. May 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- "Eritrea ranked last for first time while G8 members, except Russia, recover lost ground". Worldwide Press Freedom Index 2007. Reporters Without Borders. 19 October 2007.

- Power, Catherine. "Overview of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): Repression Revisited". World Press Freedom Review 2007. International Press Institute region review.

nine journalists remain in prison at year's end and the opposition press has all but been quashed through successive closure orders

- "Iran Report". Annual report 2008. Reporters Without Borders. 13 February 2008.

- "The Constitution of Japan", Cabinet Secretariat, Cabinet Public Relations Office, 3 November 1946, retrieved 16 March 2013

- Thestaronline.tv

- Thestar.com.my

- "The Constitution of Pakistan". pakistani.org.

- "Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom May 2009" (PDF). Pakistan. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- The relevant articles of Pakistan penal code against "Blasphemy 1) Religion 2) Quran 3) Prophets of Allah" are 295 (a), (b) and (c).

- "Chapter II. The Fundamental Rights and duties of Citizens". Constitution of the People's Republic of China. 1982-12-04. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- Republic Act No. 8491, approved February 12, 1998, Government of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Libel law violates freedom of expression – UN rights panel, The Manila Times, January 30, 2012.

- For example

- Certain sections of the Flag and Heraldic Code require particular expressions and prohibit other expressions

- Title thirteen of the Revised Penal Code of the Philippines criminalizes libel and slander by act or deed (slander by deed is defined as "any act ... which shall cast dishonor, discredit or contempt upon another person."), providing penalties of fine or imprisonment. In 2012, acting on a complaint by an imprisoned broadcaster who dramatised a newspaper account reporting that a particular politician was seen running naked in a hotel when caught in bed by the husband of the woman with whom he was said to have spent the night, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights ruled that the criminalization of libel violates freedom of expression and is inconsistent with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, commenting that "Defamations laws should not ... stifle freedom of expression" and that "Penal defamation laws should include defense of truth."

- Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom May 2009

- Google.com

- Ryu (류), Nan-yeong (난영) (2011-05-31). "유엔 인권이사회 "한국, 인터넷상 표현의 자유 훼손 심각"". Newsis (in Korean). Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- ^ "Thailand", Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2011, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State

- "Thailand Country Profile", Access Contested: Security, Identity, and Resistance in Asian Cyberspace, Ronald J. Deibert, John G. Palfrey, Rafal Rohozinski, and Jonathan Zittrain, MIT Press and the OpenNet Initiative, November 2011, ISBN 978-0-262-01678-0

- OpenNet Initiative, "Summarized global Internet filtering data spreadsheet", 8 November 2011 and "Country Profiles", the OpenNet Initiative is a collaborative partnership of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto; the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University; and the SecDev Group, Ottawa

- Due to legal concerns the OpenNet Initiative does not check for filtering of child pornography and because their classifications focus on technical filtering, they do not include other types of censorship.

- Internet Enemies, Reporters Without Borders (Paris), 12 March 2012

- "Country Report: Thailand", Freedom on the Net 2011, Freedom House, 18 April 2011

- Triple J (2004-06-30). "The story of Albert Langer". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- Amnesty International (1996-02-23). "Australia: Political activist becomes first prisoner of conscience for over 20 years (Albert Langer) – Amnesty International". Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- Media Watch (TV program) (2005-09-24). "Seditious opinion? Lock 'em up". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (Australian). Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- Chandler, Jo (2006-02-13). "Scientists bitter over interference". The Age. Melbourne.

- Explanatory Report on the additional protocol to the convention on cybercrime

- http://brnensky.denik.cz/rozhovor/halik-stat-s-krizem-pred-porodnici-prace-20090321.html

- Kolář, Petr (11 January 2013). "Prezident je buzna! Visací zámek oživil legendární píseň novým klipem [The President is a Faggot! Visací Zámek revived legendary song with a new music video]". reflex. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms the Czech Republic". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic. 2 (1993). Prague. 16 December 1992. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §180". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §184". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §191". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §287". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §355". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §356". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §356". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §364". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §365". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §404". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §405". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - "Criminal Code of the Czech Republic, §407". Collection of the laws of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 40 (2009). Prague. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - Constitution of Denmark (English translation).

- ^ Weinstein, James (2011). "Extreme Speech, Public Order, and Democracy: Lessons from The Masses". In Hare, Ivan; Weinstein, James (eds.). Extreme Speech and Democracy. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-954878-1.

- Danish Penal Code (In Danish)

- Media Liability Act (In Danish)

- Loi n° 72-546 du 1 juillet 1972 relative à la lutte contre le racisme, Journal Officiel of 2 July 1972, 6803.

- ^ Bribosia, Emmanuelle; Rorive, Isabelle; de Torres, Amaya Úbeda (2009). "Protecting Individuals from Minorities and Vulnerable Groups in the European Court of Human Rights: Litigation and Jurisprudence in France". In Anagnostou, Dia; Psychogiopoulou, Evangelia (eds.). The European Court of Human Rights and the Rights of Marginalised Individuals and Minorities in National Context. Koninklijke Brill. p. 77. ISBN 978-9004-17326-2.

- Mbongo, Pascal (2011). "Hate Speech, Extreme Speech, and Collective Defamation in French Law". In Hare, Ivan; Weinstein, James (eds.). Extreme Speech and Democracy. Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-19-954878-1.

- Loi n° 49-956 du 16 juillet 1949 sur les publications destinées à la jeunesse

- Esser, Frank; Hemmer, Katharina. "Characteristics and Dynamics of Election News Coverage in Germany". In Strömbäck, Jesper; Kaid, Lynda Lee (eds.). Handbook of Election Coverage Around the World. pp. 291–292. ISBN 978-0-8058-6037-5.

- FRA 2008, p. 24

- ^ FRA 2008, p. 23

- "Legal Study on Homophobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation – Germany" (PDF). European Union Fundamental Rights Agency. February 2008: 23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - http://www.ekloges.gr/syntagmaDetails.asp?pageid=3&langid=1&ArthroID=16

- The Fundamental Law of Hungary, 25 April 2011

- ^ Template:Hu 1978. évi IV. törvény a Büntető Törvénykönyvről (1978th Act IV. The Criminal Code) as amended, accessed 13 November 2012

- Matthew Vella. http://www.maltatoday.com.mt/2009/03/08/t13.html Maltatoday on Sunday, 8 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- "De Grondwet". www.overheid.nl. 2011-04-29.

- "28 Detained for insulting Putin?". Independent Media Center. Retrieved 2007-05-07. "Relacja z demostracji w Krakowie" (in Polish). centrum niezalez'nych medio'w Polska (Independent Media Center, Poland). Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- "Chapter 2. Fundamental rights and freedoms". The Instrument of Government. 1974. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- Summary of The Freedom of the Press Act, Swedish Riksdag

- Summary of The Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression, Swedish Riksdag

- Piano, Aili (2009). Freedom in the World 2009: The Annual Survey of Political Rights & Civil Liberties. p. 689. ISBN 978-1-4422-0122-4.

- Klug, Francesca (1996). Starmer, Keir; Weir, Stuart (eds.). The Three Pillars of Liberty: Political Rights and Freedoms in the United Kingdom. The Democratic Audit of the United Kingdom. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 978-041509642-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hensley, Thomas R. (2001). The Boundaries of Freedom of Expression & Order in American Democracy. Kent State University Press. p. 153.

- Klug 1996, pp. 175–179

- Public Order Act 1986

- Quinn, Ben (11 November 2012). "Kent man arrested after picture of burning poppy posted on internet". The Guardian.

- Section 1 of the Malicious Communications Act 1988

- ^ Joint Committee on Human Rights, Parliament of the United Kingdom (2005). Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters: Oral and Written Evidence. Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters. Vol. 2. The Stationery Office. p. 114.

- Sadurski, Wojciech (2001). Freedom of Speech and Its Limits. Law and Philosophy Library. Vol. 38. p. 179.

- Conte, Alex (2010). Human Rights in the Prevention and Punishment of Terrorism. Springer. p. 643.

- Crook, Tim (2010). Comparative Media Law and Ethics. p. 397.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Joint Committee 2005, p. 116

- "Blogger who encouraged murder of MPs jailed". BBC News. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Possession of Inspire has been successfully prosecuted under Section 58 of the Terrorism Act 2000. "Online extremist sentenced to 12 years for soliciting murder of MPs" (Press release). West Midlands Police. 29 July 2011.

In addition, Ahmad admitted three counts of collecting information likely to be of use to a terrorist, including the al-Qaeda publication Inspire. This is the first successful prosecution for possessing the online jihadist magazine.

- ^ Klug 1996, p. 177

- Lemon, Rebecca (2008). Treason by Words: Literature, Law, and Rebellion in Shakespeare's England. Cornell University Press. pp. 5–10. ISBN 9780801474491.

- Treason Felony Act 1848

- Klug 1996, p. 172

- Klug 1996, p. 173

- Klug 1996, pp. 169–170

- Klug 1996, pp. 156–160

- ^ Helsinki Watch; Fund for Free Expression (1991). Restricted Subjects: Freedom of Expression in the United Kingdom. p. 53.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "'Scandalising court' under review". BBC News. 9 August 2012.

- "Brown 'to change' protests laws". BBC News. 3 July 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

A 2005 law created an "exclusion zone" inside which all protests required police permission. ... The requirement for police permission was introduced in the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005.

- Article 16 of the Swiss Constitution

- German: 3sat TV: Switzerland's violation against Freedom of speech

- Turkish politician fined over genocide denial

- "Press Freedom Index 2008" (PDF). Reporters Without Borders. 2008.

- "Updated information on imprisoned Cuban journalists". Reporters Without Borders.

- "Private Member's Bill C-279". Parliament of Canada.

- "Imam drops rights dispute". Calgary Herald. 13 February 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Human rights complaint dismissal spurs more debate by Paul Lungen, Canadian Jewish News, 21 August 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- Mark Steyn: Canadian Islamic Congress human rights complaint, English Misplaced Pages, 7 March 2012

- "Montreal man jailed for racist website", Montreal Gazette, 24 January 2007

- Politicians allow hurt feelings to trump basic rights: http://www.canadianconstitutionfoundation.ca/article.php/188

- Supreme Court to hear appeal over anti-gay leaflets: http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/article/882255--supreme-court-to-hear-appeal-over-anti-gay-leaflets

- Murphy, Jessica (27 February 2013). "Anti-gay crusader can't distribute flyers: top court". Ottawa Sun. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Neisser, Eric (1991). Recapturing the Spirit: Essays on the Bill of Rights at 200. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-945612-23-0.

- ^ Biederman, Donald E. (2007). Law and Business of the Entertainment Industries. Law and Business of the Entertainment Industries Series. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-275-99205-7.

- 18 U.S.C. § 1001

- Protection of National Security Information (PDF), Congressional Research Service, 30 June 2006

- Miller, Roger LeRoy; Cross, Frank B.; Jentz, Gaylord A. (2008). Essentials of the Legal Environment (2 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-324-64123-3.

- DVD Copy Control Association, Inc. v. Bunner, 116 Cal. App. 4th 241

- California Government Code § 6254.21(c)

- California Penal Code § 146e

- ^ Secret Service Ordered Local Police to Restrict Anti-Bush Protesters at Rallies, ACLU Charges in Unprecedented Nationwide Lawsuit. ACLU press release, 23 September 2003

- Schauer, Frederick (February 2005). "The Exceptional First Amendment". Working Paper Series from Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government. doi:10.2139/ssrn.668543.

On this cluster of interrelated topics, there appears to be a strong international consensus that the principles of freedom of expression are either overridden or irrelevant when what is being expressed is racial, ethnic, or religious hatred. ... In contrast to this international consensus that various forms of hate speech need to be prohibited by law and that such prohibition creates no or few free speech issues, the United States remains steadfastly committed to the opposite view. ... In much of the developed world, one uses racial epithets at one's legal peril, one displays Nazi regalia and the other trappings of ethnic hatred at significant legal risk and one urges discrimination against religious minorities under threat of fine or imprisonment, but in the United States, all such speech remains constitutionally protected.

- "Pro-Israel 'Defeat Jihad' ads to hit New York subway", BBC News, 20 September 2012

- "M.T.A. Amends Rules After Pro-Israel Ads Draw Controversy", Matt Flegenheimer, New York Times, 27 September 2012

- Correa Continues Assault on Freedom of Expression in Ecuador, Freedom House, retrieved 5 May 2013

- "Ecuador's Assault on Free Speech". The New York Times. 21 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Solano, Gonzalo (17 April 2013). "Condenan a prisión a asambleísta en Ecuador". MSN Noticias (in Spanish). AP.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Reich, Otto J.; Vázquez-Ger, Ezequiel (2 May 2013). "Ecuador's Correa: A continued assault on freedom". Miami Herald.

Further reading

- Milton, John. Areopagitica: A speech of Mr John Milton for the liberty of unlicensed printing to the Parliament of England

- Hentoff, Nat. Free Speech For Me – But Not For Thee. How the American Left and Right Relentlessly Censor Each Other 1992

- Pietro Semeraro, L'esercizio di un diritto, Milano, ed. Giuffè, 2009.

External links

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange

- ARTICLE 19, Global Campaign for Free Expression

- Index on Censorship

- International PEN

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- International Federation of Journalists

- OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

- Arab Press Freedom Watch

- International Press Institute

- Fundamental Freedoms: The Charter of Rights and Freedoms – Canadian Charter of Rights website with video, audio and the Charter in over 20 languages

- "Free Speech in the Age of YouTube" in the New York Times, 22 September 2012