This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Tranquil Pepere (talk | contribs) at 13:19, 30 July 2013 (Undid revision 566421629 by Ruud Koot (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:19, 30 July 2013 by Tranquil Pepere (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 566421629 by Ruud Koot (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)In the history of mathematics, mathematics in medieval Islam, often called Islamic mathematics or Arabic mathematics, covers the body of mathematics preserved and advanced under the Islamic civilization between circa 622 and c.1600. The areas covers the Islamic caliphate established across the Middle East, extending from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Indus in the east and to the Almoravid Dynasty and Mali Empire in the south.

Omar Khayyám (c. 1038/48 in Iran – 1123/24) wrote the Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra containing the systematic solution of third-degree equations, going beyond the Algebra of Khwārazmī. Khayyám obtained the solutions of these equations by finding the intersection points of two conic sections. This method had been used by the Greeks, but they did not generalize the method to cover all equations with positive roots.

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī

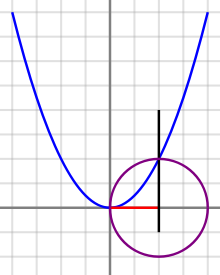

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (? in Tus, Iran – 1213/4) developed a novel approach to the investigation of cubic equations—an approach which entailed finding the point at which a cubic polynomial obtains its maximum value. For example, to solve the equation , with a and b positive, he would note that the maximum point of the curve occurs at , and that the equation would have no solutions, one solution or two solutions, depending on whether the height of the curve at that point was less than, equal to, or greater than a. His surviving works give no indication of how he discovered his formulae for the maxima of these curves. Various conjectures have been proposed to account for his discovery of them.

Other major figures

- 'Abd al-Hamīd ibn Turk (fl. 830) (quadratics)

- Thabit ibn Qurra (826–901)

- Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam (c. 850 – 930) (irrationals)

- Sind ibn Ali

- Abū Sahl al-Qūhī (c. 940–1000) (centers of gravity)

- Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi (952 – 953) (arithmetic)

- 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Qabisi

- Abū al-Wafā' Būzjānī (940 – 998) (spherical trigonometry)

- Al-Karaji (c. 953 – c. 1029) (algebra, induction)

- Abu Nasr Mansur (c. 960 – 1036) (spherical trigonometry)

- Ibn Tahir al-Baghdadi (c. 980–1037) (irrationals)

- Ibn al-Haytham (ca. 965–1040)

- Abū al-Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (973 – 1048) (trigonometry)

- Omar Khayyam (1048–1131) (cubic equations, parallel postulate)

- Ibn Yaḥyā al-Maghribī al-Samawʾal (c. 1130 – c. 1180)

- Ibn Maḍāʾ (c. 1116 - 1196)

- Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (c. 1150–1215) (cubics)

- Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (1201–1274) (parallel postulate)

- Jamshīd al-Kāshī (c. 1380–1429) (decimals and estimation of the circle constant)

See also

- Timeline of Islamic science and technology

- Islamic Golden Age

- Hindu and Buddhist contribution to science in medieval Islam

- History of geometry

Notes

- Hogendijk 1999.

- Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times, Volume 1, page 72, Oxford University Press, 1972

- Also called Greek mathematician even if they belonged to the Roman Empire

- Amongst them Diophantus and Hippathia

- http://www.math.tamu.edu/~dallen/history/infinity.pdf

- According to Kline 1972 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help), one cannot say if Babylonians were aware of the existence of an infinity of decimals or sexagesimals for the irrationnal numbers or if they believed they can convert them in a finite number of sexagesimal if they have more place in the board they used.

- Kline 1972, p. 8 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- Kline 1972, p. 32 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- Reductio ad absurdum.

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 33 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- qualified often by Alexandrians, greek mathématicians belonging to the Roman Empire

- Kline 1972, p. 104 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 185 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- Kline 1972, p. 191-192 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 192 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- (French) les nombres irrationnes se trouvent en une quantité sans comparaison plus grande que les nombres rationnels

- Jean Mawhin, Analyse, fondements, technique, évolution, De Boeck Université, Bruxelles, 1992, 1st édition, p. 38.

- Struik 1987, p. 93

- Rosen 1831, p. v–vi harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRosen1831 (help); Toomer 1990 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFToomer1990 (help)

- Corbalan, Fernando (9 2011). Le Nombre d'or: Le langage mathématique de la beauté. 1. Translated by Youssef Halaoua, Maguy Ly et Laurence Moinereau. RBA-Le Monde. p. 18.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help). - Kline 1972, p. 132 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- Today, mathematicians say that to divide a number by zero is equal to multiply it by infinity.

- G. Cifoletti, La question de l'algèbre. Mathématiques et rhétorique des hommes de droit dans la France du Template:XVIe siècle, Annales, 1995, vol. 50, p. 1385-1416, Template:Lire en ligne.

- « Algèbre d'al-ğabr » et « algèbre d'arpentage » au neuvième siècle islamique et la question de l'influence babylonienne, Fr. Mawet et Ph. Talon, D'Imhotep à Copernic. Astronomie et mathématiques des origines orientales au moyen âge. Actes du Colloque international, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 3‑4 novembre 1989. (Lettres Orientales, Leuven, Peeters, 1992 , p. 88.

- (French) Al-Khwarismi nous informe qu'il n'a pas inventé la discipline

- The algebra and the algorithms of calculus

- (French) arithmétiques utilisées constamment dans les affaires d'héritage et de legs

- Translation of Sayili, 1962.

- (French) al-Khwarismi n'a fait "que" produire une oeuvre de synthèse des disciplines et techniques des calculateurs pratiques, y compris la superstructure "pure"

- By superstructure, one can understand problems encoutered during professional life and the skill to solve them. Genuine refers to genuine mathematics or scientific mathematics used by Greek. (Summary of a note of Høyrup 1992, p. 89 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHøyrup1992 (help)).

- Cite error: The named reference

Hoyrup88was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Høyrup 1992, p. 108 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHøyrup1992 (help).

- The auteur say also that this role is probable concerning Cardan, but may be also to Viète.

- Kline 1972, p. 193 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- The name of this mathematician, latinised in Algoritmi, gived the word algorithm.

- (French) Livre sur la restauration et la confrontation

- Like in the book Farhenheit 351

- Nicolas Bourbaki, Éléments d'histoire des mathématiques, Masson, Paris, 1994, 3rd tirage, p. 69.

- The authors insinuate that Diophantus has created the x in mathematics because they don't quote any arab mathematician in the chapter devoluted to algebra.

- Kline 1972, p. 85-86 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- Corbalan 2011, p. 81 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCorbalan2011 (help).

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 119 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- The circonference is divided in 60 parts, each part is divided in 60 parts of parts. The diametra is divided in 120 parts.

- La corde est le double du côté d'un triangle rectangle inscrit dans un quadrant de cercle et ayant comme rayon l'hypothénuse. Un côté de l'angle droit d'un triangle rectangle est égal au produit de l'hypothénuse par le sinus de l'angle opposé.

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 120 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help).

- According to Kline 1972, p. 195 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKline1972 (help), The Arabs made very little progress in astronomy.

- Philip J.Davis et Reuben Hersh, L'univers mathématique, traduit par L. Chambadal, Gauthier-Villars, 1985, p. 26.

- Struik 1987, p. 96.

- Boyer 1991, pp. 241–242.

- Struik 1987, p. 97.

- Boyer & 19991, pp. 241–242. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBoyer19991 (help)

- Berggren, J. Lennart; Al-Tūsī, Sharaf Al-Dīn; Rashed, Roshdi; Al-Tusi, Sharaf Al-Din (1990), "Innovation and Tradition in Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī's al-Muʿādalāt", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 110 (2): 304–309, doi:10.2307/604533, JSTOR 604533

References

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991), "Greek Trigonometry and Mensuration, and The Arabic Hegemony", A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.), New York City: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-54397-7

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Katz, Victor J. (1993), A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, HarperCollins college publishers, ISBN 0-673-38039-4

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Ronan, Colin A. (1983), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the World's Science, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-25844-8

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, David E. (1958), History of Mathematics, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-20429-4

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Struik, Dirk J. (1987), A Concise History of Mathematics (4th rev. ed.), Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60255-9

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Bibliography

- Mathematical Tought from Ancient to Modern Times, Vol.1, Morris Kline, Oxford University Press, 1972

- Actes du Colloque International tenu à l'Université Libre de Bruxelles les 3-4 novembre 1989, D'Imhotep à Copernic, Astronomie et mathématiques des origines orientales au Moyen Âge, Lettres Orientales 2, Cahiers d'Altaïr, Édités par Fr.Mawet et Ph.Talon, Peeters-Leuven, 1992

- Le nombre d'Or, Fernando Corbalan, traduit par Youssef Halaoua, Maguy Ly, Laurence Moinereau, 2011, RBA Cillectionables S.A.

- Eléments d'histoire des mathématiques, Nicolas Bourbaki, Masson, Paris, 1994, 3eme tirage.

Further reading

- Books on Islamic mathematics

- Berggren, J. Lennart (1986), Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-96318-9

- Review: Toomer, Gerald J.; Berggren, J. L. (1988), "Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam", American Mathematical Monthly, 95 (6), Mathematical Association of America: 567, doi:10.2307/2322777, JSTOR 2322777

- Review: Hogendijk, Jan P.; Berggren, J. L. (1989), "Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam by J. Lennart Berggren", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 109 (4), American Oriental Society: 697–698, doi:10.2307/604119, JSTOR 604119)

- Daffa', Ali Abdullah al- (1977), The Muslim contribution to mathematics, London: Croom Helm, ISBN 0-85664-464-1

- Rashed, Roshdi (2001), The Development of Arabic Mathematics: Between Arithmetic and Algebra, Transl. by A. F. W. Armstrong, Springer, ISBN 0-7923-2565-6

- Youschkevitch, Adolf P. (1960), Die Mathematik der Länder des Ostens im Mittelalter, Berlin

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Sowjetische Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaft pp. 62–160. - Youschkevitch, Adolf P. (1976), Les mathématiques arabes: VIII–XV siècles, translated by M. Cazenave and K. Jaouiche, Paris: Vrin, ISBN 978-2-7116-0734-1

- Book chapters on Islamic mathematics

- Berggren, J. Lennart (2007), "Mathematics in Medieval Islam", in Victor J. Katz (ed.), The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook (Second ed.), Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University, ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Cooke, Roger (1997), "Islamic Mathematics", The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course, Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-18082-3

- Books on Islamic science

- Daffa, Ali Abdullah al-; Stroyls, J.J. (1984), Studies in the exact sciences in medieval Islam, New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-90320-5

- Kennedy, E. S. (1984), Studies in the Islamic Exact Sciences, Syracuse Univ Press, ISBN 0-8156-6067-7

- Books on the history of mathematics

- Joseph, George Gheverghese (2000), The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (2nd ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-00659-8 (Reviewed: Katz, Victor J.; Joseph, George Gheverghese (1992), "The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics by George Gheverghese Joseph", The College Mathematics Journal, 23 (1), Mathematical Association of America: 82–84, doi:10.2307/2686206, JSTOR 2686206)

- Youschkevitch, Adolf P. (1964), Gesichte der Mathematik im Mittelalter, Leipzig: BG Teubner Verlagsgesellschaft

- Journal articles on Islamic mathematics

- Høyrup, Jens. “The Formation of «Islamic Mathematics»: Sources and Conditions”. Filosofi og Videnskabsteori på Roskilde Universitetscenter. 3. Række: Preprints og Reprints 1987 Nr. 1.

- Bibliographies and biographies

- Brockelmann, Carl. Geschichte der Arabischen Litteratur. 1.–2. Band, 1.–3. Supplementband. Berlin: Emil Fischer, 1898, 1902; Leiden: Brill, 1937, 1938, 1942.

- Sánchez Pérez, José A. (1921), Biografías de Matemáticos Árabes que florecieron en España, Madrid: Estanislao Maestre

- Sezgin, Fuat (1997), Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums (in German), Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 90-04-02007-1

- Suter, Heinrich (1900), Die Mathematiker und Astronomen der Araber und ihre Werke, Abhandlungen zur Geschichte der Mathematischen Wissenschaften Mit Einschluss Ihrer Anwendungen, X Heft, Leipzig

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Television documentaries

- Marcus du Sautoy (presenter) (2008). "The Genius of the East". The Story of Maths. BBC.

- Jim Al-Khalili (presenter) (2010). Science and Islam. BBC.

External links

- Hogendijk, Jan P. (January 1999). "Bibliography of Mathematics in Medieval Islamic Civilization".

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (1999), "Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Richard Covington, Rediscovering Arabic Science, 2007, Saudi Aramco World

| Mathematics in the medieval Islamic world | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematicians |

|  | ||||||||||||||||

| Mathematical works | ||||||||||||||||||

| Concepts | ||||||||||||||||||

| Centers | ||||||||||||||||||

| Influences | ||||||||||||||||||

| Influenced | ||||||||||||||||||

| Related | ||||||||||||||||||

, with a and b positive, he would note that the maximum point of the curve

, with a and b positive, he would note that the maximum point of the curve  occurs at

occurs at  , and that the equation would have no solutions, one solution or two solutions, depending on whether the height of the curve at that point was less than, equal to, or greater than a. His surviving works give no indication of how he discovered his formulae for the maxima of these curves. Various conjectures have been proposed to account for his discovery of them.

, and that the equation would have no solutions, one solution or two solutions, depending on whether the height of the curve at that point was less than, equal to, or greater than a. His surviving works give no indication of how he discovered his formulae for the maxima of these curves. Various conjectures have been proposed to account for his discovery of them.