This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Grunt (talk | contribs) at 20:23, 12 September 2004 (Reverted edits by 206.48.0.4 to last version by Timvasquez). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:23, 12 September 2004 by Grunt (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 206.48.0.4 to last version by Timvasquez)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)- This article is about the weather phenomenon. For other uses, see Hurricane (disambiguation) or Typhoon (disambiguation).

In meteorology, a tropical cyclone (informally, a typhoon or hurricane) is a type of low-pressure system which generally forms in the tropics.

Structurally, a tropical cyclone is a large, rotating area of clouds, wind, and thunderstorm activity. The primary energy source of a tropical cyclone is the release of heat of condensation from water condensing at high altitudes. Because of this, a tropical cyclone can be thought of as a giant vertical heat engine.

This use of condensation as a driving force is the primary difference setting tropical cyclones apart from other meteorological phenomena, such as mid-latitude cyclones, which draw energy mostly from pre-existing temperature gradients in the atmosphere. To drive its heat engine, a tropical cyclone must stay over warm water, which provides the atmospheric moisture needed. The evaporation of this moisture is driven by the high winds and reduced atmospheric pressure present in the storm, resulting in a sustaining cycle.

The release of heat in the upper levels of the storm causes a temperature inversion of fifteen to twenty degrees Celsius above the ambient temperature in the lower troposphere. Because of this, tropical cyclones are referred to as "warm core" storms. Note, however, that the term "warm core" applies to the upper atmosphere – the area under a hurricane at the earth's surface is normally a few degrees cooler than normal due to clouds and precipitation.

Classification and terminology

Tropical cyclones are classified into three main groups: tropical depressions, tropical storms, and a third group whose name depends on the region.

A tropical depression is an organized system of clouds and thunderstorms with a defined surface circulation and maximum sustained winds of less than 17 metres per second (33 knots or 38 mi/h or 62 km/h).

A tropical storm is an organized system of strong thunderstorms with a defined surface circulation and maximum sustained winds between 17 and 33 metres per second (34-63 knots or 39-73 mi/h or 62-117 km/h ).

The term used to describe tropical cyclones with maximum sustained winds exceeding 33 metres per second, varies depending on region, as follows:

- hurricane in the North Atlantic Ocean, North Pacific Ocean east of the dateline, and the South Pacific Ocean east of 160°E

- typhoon in the Northwest Pacific Ocean west of the dateline

- severe tropical cyclone in the Southwest Pacific Ocean west of 160°E or Southeast Indian Ocean east of 90°E

- severe cyclonic storm in the North Indian Ocean

- tropical cyclone in the Southwest Indian Ocean

(This terminology is defined in WMO/TC-No. 560, Report No. TCP-31, World Meteorological Organization; Geneva, Switzerland; available online from http://www.bom.gov.au/bmrc/pubs/tcguide/ch1/ch1_3.htm).

In the UK and Europe some severe north-east Atlantic cyclonic depressions are referred to as "hurricanes," even although they rarely originate in the tropics. These European windstorms can generate hurricane-force windspeeds but are not given individual names.

In other places in the world, hurricanes have been called Willy-Willies (singular Willy-Willy) in Australia, Baguio in the Philippines, Chubasco in Mexico, and Taino in Haiti.

Hurricanes are categorized on a 1-to-5 scale according to the strength of their winds using the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. A Category 1 storm has the lowest wind speeds, while a Category 5 hurricane has the strongest. These are relative terms, because lower category storms can sometimes inflict greater damage than higher category storms, depending on where they strike and the particular hazards they bring. In fact, tropical storms can also produce significant damage and loss of life, mainly due to flooding.

National Hurricane Center classifies hurricanes of Category 3 or above as Major Hurricanes. Joint Typhoon Warning Center classifies typhoons with wind speeds of at least 150 mph (241 km/hr) as Super Typhoons.

The definition of sustained winds recommended by the WMO is that of a ten-minute average, and that definition is adopted by most countries. However, a few countries use different definitions: the United States, for example, defines sustained winds based on a 1-minute average wind measured at about 10 metres (33 ft) above the surface.

The ingredients for a tropical cyclone include a pre-existing weather disturbance, warm tropical oceans, moisture, and relatively light winds aloft. If the right conditions persist long enough, they can combine to produce the violent winds, incredible waves, torrential rains, and floods associated with this phenomenon.

There is also a polar counterpart to the tropical cyclone, called an arctic cyclone.

Location

Almost all tropical cyclones form within 30 degrees of the equator and 87% form within 20 degrees of it. Since the Coriolis effect initiates tropical cyclone rotation, such cyclones almost never form within about 10 degrees of the equator (where the Coriolis effect is weakest). However it is possible for tropical cyclones to form within this boundary if another source of initial rotation is provided. These conditions are extremely rare and such storms are believed to form at a rate of less than one a century.

Most tropical cyclones form in a worldwide band of thunderstorm activity known as the Inter-tropical convergence zone (ITCZ).

Worldwide, an average of 80 tropical cyclones form each year.

Major Basins

There are seven main basins of tropical cyclone formation:

- Western North Pacific Ocean: Tropical storm activity in this region frequently affects China, Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan. This is by far the most active basin, accounting for one third of all tropical cyclone activity in the world. National meteorology organizations, as well as the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) are responsible for issuing forecasts and warnings in this basin.

- Eastern North Pacific Ocean: This is the second most active basin in the world, and is also the most dense (a large number of storms for a small area of ocean). Storms which form in this basin can affect western Mexico, Hawaii and on extremely rare occasions, California. The Central Pacific Hurricane Center is responsible for forecasting the western part of this area, and the National Hurricane Center for the eastern part.

- South Eastern Pacific Ocean: Tropical activity in this region largely affects Australia and Oceania, and is forecast by Australia and New Guinea.

- Northern Indian Ocean: This basin is actually divided into two areas, the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, with the Bay of Bengal dominating (5-6 times more activity). Hurricanes which form in this basin have historically cost the most lives - most notably, the Bhola Cyclone of 1970 killed 200,000. Nations affected by this basin include India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma, and Pakistan, and all of these countries issue region forecasts and warnings. Rarely, a tropical cyclone formed in this basin will affect the Arabian Peninsula.

- Southeastern Indian Ocean: Tropical activity in this region affects Australia and Indonesia, and is forecast by those nations.

- Southwestern Indian Ocean: This basin is the least understood, due to a lack of historical data. Cyclones forming here impact Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius, and Kenya, and these nations issue forecasts and warnings for the basin.

- North Atlantic Basin: The most well studied of all tropical basins, the North Atlantic includes the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, and the Gulf of Mexico. Tropical cyclone formation here varies widely year to year, ranging from over twenty to just one. The United States, Central America, the Caribbean Islands and Canada are affected by storms in this basin. Forecasts for all storms are issued by the National Hurricane Center based in Miami, Florida ; the Canadian Hurricane Centre, based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, also issues forecasts and warnings for storms expected to affect Canadian territory and waters.

Unusual Formation Areas

The following areas spawn tropical cyclones only very rarely.

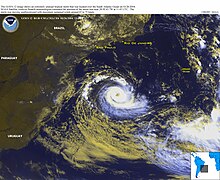

- Southern Atlantic Ocean: A combination of cooler waters, the lack of an Inter-tropical Convergence Zone, and wind shear makes it very difficult for the Southern Atlantic to support tropical activity. However, two tropical cyclones have been observed here - a weak tropical storm in 1991 off the coast of Africa, and Cyclone Catarina (sometime also referred to as Aldonça), which made landfall in Brazil in 2004.

- Central North Pacific: Shear in this area of the Pacific Ocean severely limits tropical development. However, this region is commonly frequented by tropical cyclones that form in the much more favorable Eastern North Pacific Baisin.

- Mediterranean Sea: Storms which appear similar to tropical cyclones in structure sometimes occur in the Mediterranean basin. Such cyclones formed in September 1947, September 1969, January 1982, September 1983, and January 1995. There is debate on whether these storms were tropical in nature.

Timing

Worldwide, tropical cyclone activity peaks in late summer when water temperatures are warmest. However, each particular basin has its own seasonal patterns.

In the north Atlantic, a distinct hurricane season occurs from June 1 to November 30, sharply peaking in early September. The northeast Pacific has a broader period of activity, but in a similar timeframe to the Atlantic. The northwest Pacific sees tropical cyclones year-round, with a minimum in February and a peak in early September. In the north Indian basin, storms are most common from April to December, with peaks in May and November.

In the southern hemisphere, tropical cyclone activity begins in late October, and ends in May. Southern hemisphere activity peaks in mid-February to early March.

Structure

A strong tropical cyclone consists of the following components.

- Surface low: All tropical cyclones rotate around an area of low atmospheric pressure near the earth's surface. The pressures recorded at the centers of tropical cyclones are among the lowest that occur on Earth's surface at sea level.

- Central Dense Overcast (CDO): The Central Dense Overcast is a dense shield of rain bands and thunderstorm activity surrounding the central low. Tropical cyclones with symmetrical CDO tend to be strong and well developed.

- Eye: A strong tropical cyclone will harbor an area of sinking air at the center of circulation. Weather in the eye is normally calm and free of clouds (however, the sea may be extremely violent). Eyes are home to the coldest temperatures of the storm at the surface, and the warmest temperatures at the upper levels. The eye is normally circular in shape, and may range in size from 8 km to 200 km in diameter. In weaker cyclones, the CDO covers the circulation center, resulting in no visible eye.

- Eyewall: The eyewall is a circular band of intense convection and winds immediately surrounding the eye. It is home to the most severe conditions in a tropical cyclone. Intense cyclones show eye-wall replacement cycles, in which outer eye walls form to replace inner ones. The mechanisms which make this occur are still not fully understood.

- Outflow: the upper levels of a tropical cyclone feature winds headed away from the center of the storm with an anticyclonic rotation. Winds at the surface are strongly cyclonic, weaken with height, and eventually reverse themselves - a characteristic unique to tropical cyclones.

Formation and development

The formation of tropical cyclone is still the topic of extensive research, and is still not fully understood. Five factors are necessary to make tropical cyclone formation possible:

- Sea surface temperatures above 26.5 degrees Celsius to at least a depth of 50 meters. Warm waters are the energy source for tropical cyclones. When these storms move over land or cooler areas of water they weaken rapidly.

- Upper level conditions must be conducive to thunderstorm formation. Temperatures in the atmosphere must decrease quickly with height, and the mid-troposphere must be relatively moist.

- A source of convergence. This is most frequently provided by tropical waves - non rotating areas of thunderstorms which move through the world's tropical oceans.

- A distance of more than 10 degrees from the Equator. The Coriolis Effect initiates and helps maintain the rotation of a tropical cyclone. The absence of this effect at and near the equator prohibits development.

- Lack of vertical wind shear (change in wind velocity over height). High levels of wind shear can break apart the vertical structure of a tropical cyclone, prohibiting development.

Tropical cyclones can occasionally form despite not meeting these conditions. A combination of a pre-existing disturbance, upper level divergence, and a monsoon related cold spell lead to the creation of Typhoon Vamei at only 1.5 degrees north of the equator in 2001. It is estimated that the factors leading to the formation of this typhoon repeat themselves only once every 400 years.

When a tropical cyclone of the Atlantic reaches higher latitudes and takes an eastward course, it may develop into a frontal cyclone. Such tropical-derived cyclones of higher latitudes can be violent and may occasionally remain at hurricane-force wind speeds when they reach Europe as an European windstorm.

Observations

Intense tropical cyclones pose a particular observation challenge. As they are a dangerous oceanic phenomenon, weather stations are rarely available on the site of the storm itself, unless it is passing over an island or a coastal area, or an unfortunate ship is caught in the storm. Even in these cases, real-time measurement taking is generally only possible in the periphery of the cyclone, where conditions are less catastrophic.

It is however possible to take in-situ measurements, in real-time, by sending specially equiped reconnaissance flights into the cyclone. These are flown by reinforced four-engine turboprop aircraft, which take direct and remote-sensing measurements and launch dropsondes inside the cyclone.

The cyclone can also be imaged remotely by radar, and by satellite photography in visible light and infrared.

Effects

A mature tropical cyclone can release heat at a rate upwards of 2x10 watts. This is two hundred times the total rate of human electrical production, and is equivalent to detonating a 10 megaton nuclear bomb every 20 minutes. Tropical cyclones on the open sea cause large waves, heavy rain, and high winds, disrupting international shipping and sometimes sinking ships. However, the most devastating effects of a tropical cyclone occur when they cross coastlines, making landfall. A tropical cyclone moving over land can do direct damage in 4 ways.

- High winds - Hurricane strength winds can damage or destroy vehicles, buildings, bridges, etc. High winds also turn loose debris into flying projectiles, making the outdoor environment even more dangerous.

- Storm surge - Tropical cyclones cause an increase in sea level which can flood coastal communities.

- Heavy rain - The thunderstorm activity in a tropical cyclone causes intense rainfall. Rivers and streams flood, roads become impassable, and landslides can occur.

- Tornado activity - The broad rotation of a hurricane often spawns tornadoes. While these tornadoes are normally not as strong as their non-tropical counterparts, they can still cause tremendous damage.

Often, the secondary effects of a tropical cyclone are equally damaging. They include:

- Disease - The wet environment in the aftermath of a tropical cyclone, combined with the destruction of sanitation facilities and a warm tropical climate can induce epidemics of disease which claim lives long after the storm passes.

- Power outages - Tropical cyclones often knock out power to tens of thousands of people, prohibiting vital communication and hampering rescue efforts.

- Transportation difficulties - Tropical cyclones often destroy key bridges, overpasses, and roads, complicating efforts to transport food, clean water, and medicine to the areas that need it.

Hurricanes in the Atlantic

Each year, an average of ten tropical storms develop over the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico. Many of these remain over the ocean. On average, six of these storms become hurricanes each year. In an average 3-year period, roughly five hurricanes strike the United States coastline, killing approximately 50 to 100 people anywhere from Texas to Maine. Of these, two are typically "major" or "intense" hurricanes (winds greater than 175 km/h or 110 mi/h). Hurricane season officially runs from June 1st through November 30th.

Hurricanes also strike Mexico, Central America, and Caribbean island nations, often doing intense damage: they are deadlier when over warmer water, and the United States is better able to evacuate people from threatened areas than many other nations.

In October 1998, Hurricane Mitch caused severe flooding and mudslides in Honduras, killing at least 10,000 people and changing the landscape enough that entirely new maps of the nation were needed.

In August, 1992, Hurricane Andrew became the most destructive hurricane in the history of the United States of America.

On March 26, 2004, Cyclone Catarina became the first-ever hurricane observed in the south Atlantic Ocean. Previous South Atlantic cyclones in 1991 and 2004 reached only tropical storm strength. Hurricanes may have formed there prior to 1960 but were not observed until weather satellites began monitoring the Earth's oceans in that year.

Notable cyclones

On Christmas Day 1974, Tropical cyclone Tracy hit Darwin, Australia. It was the most devastating natural disaster to have ever hit an Australian city. Around 90% of the homes in Darwin were destroyed. Fifty people died in Darwin, and sixteen at sea. Authorities managed to evacuate most of Darwin. Although cyclone Tracy was quite small, it was very severe, with winds of up to 217 kilometres per hour. The damage was estimated to be close to $A 400 million, which (at current exchange rates) is approximately equal to $US 280 million.

A 100-mph tropical cyclone hit the densely populated Ganges Delta region of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) on November 13, 1970, which killed an estimated 500,000 people (this is regarded as the 20th century's worst cyclone disaster).

The Galveston Hurricane of 1900, which made landfall at Galveston, Texas as an estimated category 4 storm, killed 6,000-12,000 people. It remains the United States' deadliest natural disaster.

Naming of tropical cyclones

Tropical cyclones with winds exceeding 33 metres per second are given names. These names are taken from lists which vary from region to region. The lists are decided upon either by national meteorological organizations, or by committees of the World Meteorological Organization.

To help in their identification, in the early 1950's the practice of naming tropical storms and hurricanes was initiated by the United States National Hurricane Center and are now maintained by the WMO. In keeping with the common English language practice of referring to inanimate objects such as boats, trains, etc., using the female pronoun "she", names used were exclusively female. The first storm of the year was assigned a name beginning with the letter "A", the second with the letter "B", etc. However, since tropical storms and hurricanes are primarily destructive, some considered this practice sexist. The National Weather Service responded to these concerns in 1979 with the introduction of male names to the nomenclature. Currently, female and male names during a given season are assigned alternately, still in alphabetic order. The "gender" of the first storm of the season also alternates year to year. The lists of names is prepared in advance, and reused periodically, except that the names of particularly destructive storms are "retired".

Other sets of names are used in the Eastern North Pacific, Central North Pacific, and the Western North Pacific, maintained by the WMO Typhoon Committee. The Australian Bureau of Meteorology maintains three lists of names, one for each of the Western, Northern and Eastern Australian regions. There are also Fiji region and Papua New Guinea region names. The Seychelles Meteorological Service maintains a list for the Southwest Indian Ocean.

See also

- arctic cyclone

- Beaufort scale

- neutercane

- subtropical cyclone

- list of Atlantic hurricane seasons.

- list of notable tropical cyclones

- lists of tropical cyclone names

External links

- An excellent hurricane FAQ

- Global climatology of tropical cyclones

- List of available tropical cyclone names

- List of retired tropical cyclone names

- Naming hurricanes

- Unisys historical and contemporary hurricane track data e.g. Atlantic 1968

- Worldwide tropical cyclone tracks, 1979-1988

- Worldwide tropical cyclone basins

- 1995 Mediterranean "Hurricane"

- Tropical cyclone peak activity rates for different basins