This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sandstein (talk | contribs) at 04:47, 14 June 2006 (→Male alternatives: remove references to fringe neologisms, see Misplaced Pages:Articles for deletion/Men's fashion freedom and Misplaced Pages:Articles for deletion/Male Unbifurcated Garment). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:47, 14 June 2006 by Sandstein (talk | contribs) (→Male alternatives: remove references to fringe neologisms, see Misplaced Pages:Articles for deletion/Men's fashion freedom and Misplaced Pages:Articles for deletion/Male Unbifurcated Garment)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Clothing is defined, in its broadest sense, as coverings for the torso and limbs as well as coverings for the hands (gloves), feet (socks, shoes, sandals, boots) and head (hats, caps). Humans nearly universally wear clothing, which is also known as dress, garments, attire, or apparel. People wear clothing for functional as well as for social reasons. Clothing protects the vulnerable nude human body from the extremes of weather and other features of our environment. But every article of clothing also carries a cultural and social meaning.

Humans also decorate their bodies with makeup or cosmetics, perfume, and other ornamentation; they also cut, dye, and arrange the hair of their heads, faces, and bodies (see hairstyle), and sometimes also mark their skin (by tattoos, scarifications, and piercings). All these decorations contribute to the overall effect and message of clothing, but do not constitute clothing per se.

Articles carried rather than worn (such as purses, canes, and umbrellas) are normally counted as fashion accessories rather than as clothing. Jewelry and eyeglasses are usually counted as accessories as well, even though in common speech these items are described as being worn rather than carried.

Clothing as functional technology

The practical function of clothing is to protect the human body from weather — strong sunlight, extreme heat or cold, and precipitation — as well as protect from insects, noxious chemicals, weapons, and contact with abrasive substances. In sum, clothing protects against anything that might injure the naked human body. Humans have shown extreme inventiveness in devising clothing solutions to practical problems.

See: armor, diving suit, swimsuit, bee-keeper's costume, motorcycle leathers, high-visibility clothing, and protective clothing.

Clothing as social message

Social messages sent by clothing, accessories, and decorations can involve social status, occupation, ethnic and religious affiliation, marital status and sexual availability, etc. Humans must know the code in order to recognize the message transmitted. If different groups read the same item of clothing or decoration with different meanings, the wearer may provoke unanticipated and/or unwanted responses.

The manner of consciously constructing, assembling, and wearing clothing to convey a social message in any culture is governed by current fashion. The rate at which fashion changes varies; easily modified styles in wearing or accessorizing clothes can change in months, even days, in small groups or in media-influenced modern societies. More extensive changes, that may require more time, money, or effort to effect, may span generations. When fashion changes, messages from clothing change.

Social status

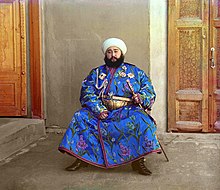

In many societies, people of high rank reserve special items of clothing or decoration for themselves as symbols of their social status. In ancient times, only Roman senators could wear garments dyed with Tyrian purple; only high-ranking Hawaiian chiefs could wear feather cloaks and palaoa or carved whale teeth. In China before the establishment of the republic, only the emperor could wear yellow. In many cases throughout history, there have been elaborate systems of sumptuary laws regulating who could wear what. In other societies (including most modern societies), no laws prohibit lower-status people from wearing high-status garments, but the high cost of status garments effectively limits purchase and display. In current Western society, only the rich can afford haute couture. The threat of social ostracism may also limit garment choice.

Occupation

Military, police, and firefighters usually wear uniforms, as do workers in many industries. School children often wear school uniforms, while college and university students sometimes wear academic dress. Members of religious orders may wear uniforms known as habits. Sometimes a single item of clothing or a single accessory can declare one's occupation or rank within a profession — for example, the high toque or chef's hat worn by a chief cook.

See also undercover.

Ethnic, political, and religious affiliation

In many regions of the world, national costumes and styles in clothing and ornament declare membership in a certain village, caste, religion, etc. A Scotsman declares his clan with his tartan. A Sikh displays his religious affiliation by wearing a turban and other traditional clothing. A French peasant woman would have identified her village with her cap or coif.

Clothes can also proclaim dissent from cultural norms and mainstream beliefs, as well as personal independence. In 19th-century Europe, artists and writers lived la vie de Bohème and dressed to shock: George Sand in men's clothing, female emancipationists in bloomers, male artists in velvet waistcoats and gaudy neckcloths. Bohemians, beatniks, hippies, Goths, Punks and Skinheads have continued the (countercultural) tradition in the 20th-century West. Now that haute couture plagiarizes street fashion within a year or so, street fashion may have lost some of its power to shock, but it still motivates millions trying to look hip and cool.

Marital status

Hindu women, once married, wear sindoor, a red powder, in the parting of their hair; if widowed, they abandon sindoor and jewelry and wear simple white clothing. Men and women of the Western world may wear wedding rings to indicate their marital status. See also Visual markers of marital status.

Sexual interest

Some clothing indicates the modesty of the wearer. For example, many Muslim women wear head or body covering (see hijab, burqa or bourqa, chador and abaya) that proclaims their status as respectable women. Other clothing may indicate flirtatious intent. For example, a Western woman might wear extreme stiletto heels, close-fitting and body-revealing black or red clothing, exaggerated make-up, flashy jewelry and perfume to show sexual interest. A man might wear a tightly-cut shirt and unbutton the top buttons.

What constitutes modesty and allurement varies radically from culture to culture, within different contexts in the same culture, and over time as different fashions rise and fall. Moreover, a person may choose to display a mixed message. For example, a Saudi Arabian woman may wear an abaya to proclaim her respectability, but choose an abaya of luxurious material cut close to the body and then accessorize with high heels and a fashionable purse. All the details proclaim sexual desirability, despite the ostensible message of respectability.

Male alternatives

The cross-dressing and transgender communities wear clothing associated with their non-birth sex with an awareness of gender. On the other hand, skirts, kilts and sarongs — usually associated with women in the West — are common men's clothing in Asia and in some African countries. Kilts are part of the traditional Celtic dress. The foustanella is worn in Southern Europe. Both Scottish and Turkish military units include such clothing, while the cassock is common amongst Christian clergy.

Regional variations of male skirts or kilts include the lava-lava in Polynesia, caftans in the Mediterranean, robes, tupenus in South Asia and Oceania, dashiki in West Africa, hakama in Japan, the Moroccan djellaba, and lungis in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. Finally, there are attempts to introduce contemporary kilts as menswear in the West.

Sexual fetishes involving clothing

Because clothing and adornment are closely related to ideas of human sexuality and sexual display, humans may develop clothing fetishes. They may be strongly aroused by the sight of another person wearing clothing and accessories they consider arousing or sexually exciting. Sometimes the object of clothing becomes the object of arousal itself. Fetishes have been documented in every culture and have been recorded throughout history. Common fetishes involving clothing include arousal by or involving shoes, leather, uniforms, or lingerie.

Fetishes vary as much as fashion. Sometimes the clothing itself becomes the object of fetish, such as in case with used girl panties in Japan. Some clothing manufacturers make fetish clothing, designed to arouse buyers with specialized tastes.

Religious habits and special religious clothing

Religious clothing might be considered a special case of occupational clothing. Sometimes it is worn only during the performance of religious ceremonies. However, it may also be worn everyday as a marker for special religious status.

See also, Religious vesture.

Clothing materials

Common clothing materials include:

- Cloth, typically made of cotton, flax, wool, hemp, ramie, silk, or synthetic fibers

- Down for down-filled parkas

- Fur

- Leather

Less-common clothing materials include:

Reinforcing materials such as wood, bone, plastic and metal may be used in fasteners or to stiffen garments.

Clothing maintenance

Clothing, once manufactured, suffers assault both from within and from without. The human body inside sheds skin cells and body oils, and exudes sweat, urine, and feces. From the outside, sun damage, damp, abrasion, dirt, and other indignities afflict the garment. Fleas and lice take up residence in clothing seams. Well-worn clothing, if not cleaned and refurbished, will smell, itch, look scruffy, and lose functionality (as when buttons fall off and zippers fail).

In some cases, people simply wear an item of clothing until it falls apart. Cleaning leather presents difficulties; one cannot wash bark cloth (tapa) without dissolving it. Owners may patch tears and rips, and brush off surface dirt, but old leather and bark clothing will always look old.

But most clothing consists of cloth, and most cloth can be laundered and mended (patching, darning, but compare felt).

Humans have developed many specialized methods for laundering, ranging from the earliest "pound clothes against rocks in running stream" to the latest in electronic washing machines and dry cleaning (dissolving dirt in solvents other than water).

In past times, mending was an art. A meticulous tailor or seamstress could mend rips with thread raveled from hems and seam edges so skillfully that the darn was practically invisible. When the raw material — cloth — was worth more than labor, it made sense to expend labor in saving it. Today clothing is considered a consumable item. Mass-manufactured clothing is less expensive than the time it would take to repair it. Many people prefer to buy a new piece of clothing rather than to spend their time mending old clothes. But the thrifty still replace zippers and buttons and sew up ripped hems.

The life cycle of clothing

Used, no-longer-wearable clothing was once desirable raw material for quilts, rag rugs, bandages, and many other household uses. It could also be recycled into paper. Now it is usually just tossed into the trash. Used but still wearable clothing can be sold at consignment shops, flea markets, online auction, or just donated to charity. Charities usually skim the best of the clothing to sell in their own thrift stores and sell the rest to merchants, who bale it up and ship it to poor Third World countries, where vendors bid for the bales and then make what profit they can selling used clothing. They used these cloths to help other people to do things.

Early 21st-century clothing styles

Western fashion has to a certain extent become international fashion, as Western media and styles penetrate all parts of the world. Very few parts of the world remain where people do not wear items of cheap, mass-produced Western clothing. Even people in poor countries can afford used clothing from richer Western countries.

However, people may wear ethnic or national dress on special occasions or if carrying out certain roles or occupations. For example, most Japanese women have adopted Western-style dress for daily wear, but will still wear expensive silk kimonos on special occasions. Items of Western dress may also appear worn or accessorized in distinctive, non-Western ways. A Tongan man may combine a used T-shirt with a Tongan wrapped skirt, or tupenu.

Western fashion, too, does not function monolithically. It comes in many varieties, from expensive haute couture to thrift store grunge.

Mainstream Western or international styles

- International standard business attire — global in influence, just as business functions globally.

- Haute couture

- Casual wear

Regional styles

- For example: "Catalogue" fashion, regional styles such as preppy or Western wear.

- These fashions are often associated with fans of various musical styles.

- See also Goth, Hippie, Grunge, Hip-hop, and Fetish-wear

Origin and history of clothing

According to archaeologists and anthropologists, the earliest clothing probably consisted of fur, leather, leaves or grass, draped, wrapped or tied about the body for protection from the elements. Knowledge of such clothing remains inferential, since clothing materials deteriorate quickly compared to stone, bone, shell and metal artifacts. Archeologists have identified very early sewing needles of bone and ivory from about 30,000 BC, found near Kostenki, Russia, in 1988.

Ralf Kittler, Manfred Kayser and Mark Stoneking, anthropologists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, have conducted a genetic analysis of human body lice that indicates that they originated about 107,000 years ago. Since most humans have very sparse body hair, body lice require clothing to survive, so this suggests a surprisingly recent date for the invention of clothing. Its invention may have coincided with the spread of modern Homo sapiens from the warm climate of Africa, thought to have begun between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. However, a second group of reseachers used similar genetic methods to estimate that body lice originated about 540,000 years ago (Reed et al. 2004. PLoS Biology 2(11): e340). For now, the date of the origin of clothing remains unresolved.

Some human cultures, such as the various peoples of the Arctic Circle, until recently made their clothing entirely of furs and skins, cutting clothing to fit and decorating lavishly.

Other cultures have supplemented or replaced leather and skins with cloth: woven, knitted, or twined from various animal and vegetable fibres. See weaving, knitting, and twining.

Although modern consumers take clothing for granted, making the fabrics that go into clothing is not easy. One sign of this is that the textile industry was the first to be mechanized during the Industrial Revolution; before the invention of the powered loom, textile production was a tedious and labor-intensive process. Therefore, methods were developed for making most efficient use of textiles.

One approach simply involves draping the cloth. Many peoples wore, and still wear, garments consisting of rectangles of cloth wrapped to fit — for example, the Scottish kilt or the Javanese sarong. Pins or belts hold the garments in place. The precious cloth remains uncut, and people of various sizes can wear the garment.

Another approach involves cutting and sewing the cloth, but using every bit of the cloth rectangle in constructing the clothing. The tailor may cut triangular pieces from one corner of the cloth, and then add them elsewhere as gussets. Traditional European patterns for men's shirts and women's chemises take this approach.

Modern European fashion treats cloth much more prodigally, typically cutting in such a way as to leave various odd-shaped cloth remnants. Industrial sewing operations sell these as waste; home sewers may turn them into quilts.

In the thousands of years that humans have spent constructing clothing, they have created an astonishing array of styles, many of which we can reconstruct from surviving garments, photos, paintings, mosaics, etc., as well as from written descriptions. Costume history serves as a source of inspiration to current fashion designers, as well as a topic of professional interest to costumers constructing for plays, films, television, and historical reenactment.

- See also History of Western fashion

Future trends

As technologies change, so will clothing. Many people, including futurologists have extrapolated current trends and made the following predictions:

- Man-made fibers such as nylon, polyester, Lycra, and Gore-Tex already account for much of the clothing market. Many more types of fibers will certainly be developed, possibly using nanotechnology. For example, military uniforms may stiffen when hit by bullets, filter out poisonous chemicals, and treat wounds.

- "Smart" clothing will incorporate electronics. Clothing may incorporate wearable computers, flexible wearable displays (possibly leading to fully animated clothing and some forms of invisibility cloaks), medical sensors, etc.

- Present-day ready-to-wear technologies will presumably give way to computer-aided custom manufacturing. Low power laser beams will measure the customer; computers will draw up a custom pattern and execute it in the customer's choice of cloth.

Clothing industry

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The clothing industry is concentrated outside of western Europe and America, and garment workers often have to labor under poor conditions. Coalitions of NGO's, designers (Katharine Hamnett, American Apparel, Veja, Edun,...) and trade unions like the Clean clothes campaign (CCC) seek to improve these conditions as much as possible by sponsoring awareness-raising events, which draw the attention of both the media and the general public to the workers' conditions.

See also

See also: List of types of clothing and Clothing terminology.

For the alternative to clothing — wearing nothing — see nudity.

External links

- The Internet Public Library - Clothing resources

- La Couturière Parisienne

- Japanese scientist invents 'invisibility coat' - BBC News

- German Hosiery Museum (English language)

- International Clothes Sizes

- Molecular Evolution of Pediculus humanus and the Origin of Clothing by Ralf Kittler, Manfred Kayser and Mark Stoneking (.PDF file)