This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) at 21:26, 5 November 2014 (Reverting possible vandalism by 208.35.154.138 to version by Vzaak. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (2018596) (Bot)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:26, 5 November 2014 by ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) (Reverting possible vandalism by 208.35.154.138 to version by Vzaak. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (2018596) (Bot))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other treaties of Paris, see Treaty of Paris (disambiguation).| The Definitive Treaty of Peace Between Great Britain and the United States of America | |

|---|---|

| Drafted | 30 November, 1782 |

| Signed | 3 September 1783 |

| Location | Paris, France |

| Effective | 12 May, 1784 |

| Condition | Ratification by Great Britain and the United States |

| Signatories | |

| Depositary | United States Government |

| Language | English |

| Full text | |

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of King George III of Great Britain and representatives of the United States of America on 3 September 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War. It, along with the separate peace treaties between Great Britain and the nations that supported the American cause: France, Spain and the Dutch Republic, are known collectively as the Peace of Paris. Its territorial provisions were "exceedingly generous" to the United States in terms of enlarged boundaries.

Agreement

Peace negotiations began in April of 1782, involving American representatives Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Henry Laurens, and John Adams. The British representatives present were David Hartley and Richard Oswald.

The treaty was signed in Paris at the Hotel d'York (presently 56 Rue Jacob), by Adams, Franklin, Jay, and Hartley.

Franklin was almost successful in getting Britain to cede the Province of Quebec (today's eastern Canada) to the United States because he hoped to control all of North America. The British at first agreed, then rejected the proposal.

On September 3, 1783, Great Britain also signed separate agreements with France and Spain, and (provisionally) with the Netherlands. In the treaty with Spain, the territories of East and West Florida were ceded to Spain (without a clear northern boundary, resulting in a territorial dispute resolved by the Treaty of Madrid in 1795), as was the island of Minorca, while the Bahama Islands, Grenada, and Montserrat, captured by the French and Spanish, were returned to Britain. The treaty with France was mostly about exchanges of captured territory (France's only net gains were the island of Tobago, and Senegal in Africa), but also reinforced earlier treaties, guaranteeing fishing rights off Newfoundland. Dutch possessions in the East Indies, captured in 1781, were returned by Britain to the Netherlands in exchange for trading privileges in the Dutch East Indies, by a treaty which was not finalized until 1784.

The United States Congress of the Confederation ratified the Treaty of Paris on January 14, 1784. Copies were sent back to Europe for ratification by the other parties involved, the first reaching France in March 1784. British ratification occurred on April 9, 1784, and the ratified versions were exchanged in Paris on May 12, 1784. It was not for some time, though, that the Americans in the countryside received the news because of the lack of speedy communication.

Treaty key points

Preamble. Declares the treaty to be "in the name of the most holy and undivided Trinity", states the bona fides of the signatories, and declares the intention of both parties to "forget all past misunderstandings and differences" and "secure to both perpetual peace and harmony".

- Acknowledging the United States (viz. the Colonies) to be free, sovereign and independent states, and that the British Crown and all heirs and successors relinquish claims to the Government, property, and territorial rights of the same, and every part thereof;

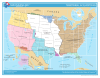

- Establishing the boundaries between the United States and British North America;

- Granting fishing rights to United States fishermen in the Grand Banks, off the coast of Newfoundland and in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence;

- Recognizing the lawful contracted debts to be paid to creditors on either side;

- The Congress of the Confederation will "earnestly recommend" to state legislatures to recognize the rightful owners of all confiscated lands and "provide for the restitution of all estates, rights, and properties, which have been confiscated belonging to real British subjects" (Loyalists);

- United States will prevent future confiscations of the property of Loyalists;

- Prisoners of war on both sides are to be released; all property of the British army (including slaves) now in the United States is to remain and be forfeited;

- Great Britain and the United States are each to be given perpetual access to the Mississippi River;

- Territories captured by Americans subsequent to the treaty will be returned without compensation;

- Ratification of the treaty is to occur within six months from its signing.

Eschatocol. "Done at Paris, this third day of September in the year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-three."

Consequences

Historians have often commented that the treaty was very generous to the United States in terms of greatly enlarged boundaries, which came at the expense of the Native allies of the British. The point was the United States would be a major trading partner. As the French foreign minister Vergennes later put it, "The English buy peace rather than make it".

Privileges that the Americans had received from Britain automatically when they had colonial status (including protection from pirates in the Mediterranean Sea; see: the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War) were withdrawn. Individual states ignored federal recommendations, under Article 5, to restore confiscated Loyalist property, and also dishonored Article 6 (e.g., by confiscating Loyalist property for "unpaid debts"). Some, notably Virginia, also defied Article 4 and maintained laws against payment of debts to British creditors. Individual British soldiers ignored the provision of Article 7 about removal of slaves.

The actual geography of North America turned out not to match the details used in the treaty. The Treaty specified a southern boundary for the United States, but the separate Anglo-Spanish agreement did not specify a northern boundary for Florida, and the Spanish government assumed that the boundary was the same as in the 1763 agreement by which they had first given their territory in Florida to Britain. While that West Florida Controversy continued, Spain used its new control of Florida to block American access to the Mississippi, in defiance of Article 8. In the Great Lakes area, the British adopted a very generous interpretation of the stipulation that they should relinquish control "with all convenient speed", because they needed time to negotiate with the Native Americans, who had kept the area out of United States control, but had been completely ignored in the Treaty. Even after that was accomplished, Britain retained control as a bargaining counter in hopes of obtaining some recompense for the confiscated Loyalist property. This matter was finally settled by the Jay Treaty in 1794, and America's ability to bargain on all these points was greatly strengthened by the creation of the new constitution in 1787.

See also

- Ratification Day (United States)

- Peace of Paris (1783)

- List of United States treaties

- History of the United States (1776–89)

- Diplomacy in the American Revolutionary War

Notes and references

- "British-American Diplomacy Treaty of Paris - Hunter Miller's Notes". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- Morris 1965

- Jeremy Black, British foreign policy in an age of revolutions, 1783–1793 (1994) pp 11–20

- Quote from Thomas Paterson, J. Garry Clifford and Shane J. Maddock, American foreign relations: A history, to 1920 (2009) vol 1 p 20

- http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/paris.asp

- David Waldstreicher (2011). A Companion to Benjamin Franklin. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 367–68.

- Francis M. Carroll (2001). A Good and Wise Measure: The Search for the Canadian-American Boundary, 1783-1842. University of Toronto Press. p. 8.

- Frances G, Davenport and Charles O. Paullin, European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies (1917) vol 1 p vii

- Gerald Newman and Leslie Ellen Brown, Britain in the Hanoverian age, 1714–1837 (1997) p. 533

- Quote from Thomas Paterson, J. Garry Clifford and Shane J. Maddock, American foreign relations: A history, to 1920 (2009) vol 1 p 20

- Jones, Howard (2002). Crucible of Power: A History of American Foreign Relations to 1913. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8420-2916-2.

- Benn, Carl (1993). Historic Fort York, 1793–1993. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-920474-79-2.

Further reading

- Dull, Jonathan R. (1987). A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03886-0. ch 17–20

- Hoffman, Ronald; Peter J. Albert editor (1981). Diplomacy and Revolution: The Franco-American Alliance of 1778. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-0864-7.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - Hoffman, Ronald; Peter J. Albert editor (1986). Peace and the Peacemakers: The Treaty of 1783. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1071-4.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - Kaplan, Lawrence S. "The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Historiographical Challenge," International History Review, Sept 1983, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp 431–442

- Morris, Richard B. The Peacemakers; the Great Powers and American Independence (1965), the standard scholarly history

- Perkins, James Breck (1911). "Negotiations for Peace". France in the American Revolution. Houghton Mifflin.

- Stockley, Andrew (2001). Britain and France at the Birth of America: The European Powers and the Peace Negotiations of 1782–1783. University of Exeter Press.

- Franklin, Benjamin (1906). The Writings of Benjamin Franklin. The Macmillan company.

External links

- Treaty of Paris, 1783; International Treaties and Related Records, 1778–1974; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11; National Archives.

- Approval of the American victory in England Unique arch inscription commemorates "Liberty in N America Triumphant MDCCLXXXIII"

- The Paris Peace Treaty of September 30, 1783 Text of the treaty provided by Yale Law School's Avalon Project

| Territorial expansion of the United States | ||

|---|---|---|

|  | |

| ||

| Benjamin Franklin | |

|---|---|

| Founding of the United States |

|

| Inventions, other events |

|

| Writings |

|

| Legacy |

|

| In popular culture |

|

| Related | |

| Family |

|

| John Adams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founding of the United States |

|

| Elections | |

| Presidency |

|

| Other writings | |

| Life and homes | |

| Legacy |

|

| Popular culture |

|

| Related | |

| Adams political family |

|

| |

- 1783 in Great Britain

- 1783 in the United States

- 1784 in the United States

- Treaties of the United States

- Peace treaties of the United States

- Diplomacy during the American Revolutionary War

- 1783 in France

- Boundary treaties

- Canada–United States border

- Peace treaties of Great Britain

- 1783 treaties

- 1784 treaties

- 18th century in Paris