This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Riapress (talk | contribs) at 04:07, 13 July 2006 (→External links). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:07, 13 July 2006 by Riapress (talk | contribs) (→External links)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

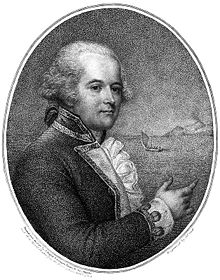

Vice-Admiral William Bligh, FRS (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was an officer of the British Royal Navy and colonial administrator. He is best known for the famous mutiny that occurred against his command aboard HMAV (His Majesty's Armed Vessel) Bounty and the remarkable voyage he made to Timor on the Bounty's launch after being set adrift by the mutineers. Many years after the Bounty mutiny he was appointed Governor of New South Wales, with a brief to clean up the corrupt rum trade of the NSW Corps. He had some success in his task but quickly faced opposition which culminated in the Rum Rebellion led by John Macarthur.

Although William Bligh was certainly not the vicious man portrayed in popular fiction, some claim his over-sensitivity and acid tongue damaged what would have otherwise been a distinguished career.

Early life

Bligh was born on September 9, 1754 to Francis and Jane Bligh (née Balsam) in Tinten Manor, St Tudy, Cornwall. He was signed up for the sea at the age of seven in Plymouth, Devon, a seaport in south-west England. Whether he went to sea at this tender age is doubtful, as it was common practice to sign on a "young gentleman" simply in order to rack up the required years of service for quick promotion. In 1776, he was selected by Captain James Cook for the position of Sailing Master on the Resolution and accompanied Captain Cook in July 1776 on Cook's third and fatal voyage to the Pacific. He reached England again at the end of 1780 and was able to give further details of Cook's last voyage. In 1787 he was selected as commander of the HMAV Bounty. He would eventually rise to the rank of Vice Admiral in the British Navy.

He married Elizabeth Betham, the daughter of a Customs Collector on 4 February 1781 and a few days thereafter he was appointed to serve on 'Belle Poule' as its master. Soon after this in August 1781 he fought in the battles of Dogger Bank under Admiral Parker. For the next 18 months he was a lieutenant on various ships. He also fought with Lord Howe at Gibraltar in 1782. Between 1783 and 1787 he was a captain in the merchant service.

Naval career

William Bligh's naval career consisted of a variety of appointments and assignments. A summary is as follows:

- July 1, 1762: Ship's Boy and Captain's Servant, HMS Monmouth

- July 27, 1770: Able Seaman, HMS Hunter

- February 5 1771: Midshipman, HMS Hunter

- September 22, 1771: Midshipman, HMS Crescent

- September 2, 1774: Able Seaman, HMS Ranger

- September 30, 1775: Master's Mate, HMS Ranger

- March 20, 1776: Master, HMS Resolution

- February 14, 1781: Master, HMS Belle Poule

- October 5, 1781: Lieutenant, HMS Berwick

- January 1, 1782: Lieutenant, HMS Princess Amelia

- March 20, 1782: Lieutenant, HMS Cambridge

- January 14, 1783: Joined Merchant Service as Lieutenant

- 1785: Commanding Lieutenant, Merchant Vessel Lynx

- 1786: Lieutenant, Merchant Vessel Britannia

- 1787: Returns to Royal Navy active service

- August 16, 1787: Commanding Lieutenant, HMAV Bounty

- November 14, 1790: Captain, HMS Falcon

- December 15, 1790: Captain, HMS Medea

- April 16, 1791: Captain, HMS Providence

- April 30, 1795: Captain, HMS Calcutta

- January 7, 1796: Captain, HMS Director

- March 18, 1801: Post Captain, HMS Glatton

- April 12, 1801: Post Captain, HMS Monarch

- May 8, 1801: Post Captain, HMS Irresistible

- May 2, 1804: Post Captain, HMS Warrior

- May 14, 1805: Governor of New South Wales

- September 27, 1805: Post Captain, HMS Porpoise

- July 31, 1808: Commodore, HMS Porpoise

- April 3, 1810: Commodore, HMS Hindostan

- July 31, 1810: Appointed Rear Admiral of the Blue

- June 4, 1814: Appointed Vice Admiral of the Blue

The voyage of the Bounty

In 1787, Bligh took command of the Bounty. He first sailed to Tahiti to obtain breadfruit trees, then set course for the Caribbean, where breadfruit was wanted for experiments to see if it would be a successful food crop for slaves there. The Bounty never reached the Caribbean, as mutiny broke out onboard shortly after leaving Tahiti. In later years, Bligh would repeat the same voyage that the Bounty had undertaken and would eventually succeed in delivering the breadfruit to the West Indies. Bligh's mission may have introduced the Ackee to the Caribbean as well, though this is uncertain. (Ackee is now called Blighia sapida in binomial nomenclature, after Bligh).

The voyage was difficult. After trying unsuccessfully for a month to round Cape Horn, the Bounty was finally defeated by the notoriously stormy weather and forced to take the long way around the Cape of Good Hope. That delay resulted in a further delay in Tahiti as they had to wait 5 months for the breadfruit plants to mature enough to be transported. The 'Bounty' departed Tahiti in April 1789.

Without a member of the Marine Corps on board for protection in case of mutiny, and no lieutenant aboard, he was obliged to rely on Fletcher Christian as his first mate (Acting Lieutenant). The mutiny, which broke out during the return voyage on April 28, 1789, was led by Master's Mate (at the time promoted by Bligh to Acting Lieutenant) Fletcher Christian and supported by a quarter of the crew. Despite their being in the majority, none of the loyalists seemed to have put up any significant struggle, and the ship was taken bloodlessly. The mutineers provided Bligh and the eighteen of his crew who remained loyal with a 23 foot (7 m) launch, with four cutlasses and food and water for a few days to reach the most accessible ports, a compass and a pocket watch, but no charts or sextant. The launch could not hold all the loyal crew members, and four were detained on the Bounty by the mutineers for their useful skills; these were later released at Tahiti.

Popular fiction claims that out of bloody-mindedness Bligh disdained an easy course of action of sailing for the nearby island of Tofua or "nearby Spanish ports" where they would be repatriated to Britain after delays. In fact, Bligh had no alternative.

Tahiti was upwind from his position, and was the obvious destination of the mutineers. Many of the loyalists claimed to have heard the mutineers cry "Huzzah for Otaheite!" as the Bounty pulled away. Timor was the nearest European outpost (there were no "nearer Spanish ports"). Bligh and his crew did make for Tofua first to get supplies; there they were attacked by hostile natives and a crewman was killed. After fleeing Tofua, Bligh didn't dare stop at the next islands (the Fiji islands) as he had no weapons for defense and the Fijians at that time were cannibals.

Bligh had a well-deserved confidence in his navigational skills. His first responsibility was to survive and get word of the mutiny as soon as possible to British vessels that could pursue the mutineers. Thus, he undertook the seemingly-impossible 3618 nautical mile (6701 km) voyage to Timor. In this remarkable act of seamanship, Bligh succeeded in reaching Timor after a 41-day voyage, with the only casualty being the crewman killed on Tofua. Ironically, several of the men who survived this ordeal with him soon died of sickness, possibly malaria, in the pestilential Dutch East Indies port of Batavia as they waited for transport to England.

To this day, the reasons for the mutiny are a subject of considerable debate. Some feel that Bligh was a cruel tyrant whose abuse of the crew led members of the crew to feel that they had no choice but to take the ship from Bligh. Others feel that the crew, inexperienced and unused to the rigours of the sea, and after having been exposed to freedom and sexual excess on the island of Tahiti, refused to return to the "Jack Tars" existence of a seaman. They were "led" by a weak Fletcher Christian, and were only too happy to be free from Bligh's acid tongue. They hold that the crew took the ship from Bligh so that they could return to a life of comfort and pleasure on Tahiti.

Bligh returned to London arriving in March 1790.

The Bounty's log shows that Bligh resorted to punishments sparingly. He scolded when other captains would have whipped, and whipped when other captains would have hanged. He was an educated man, deeply interested in science, convinced that good diet and sanitation were necessary for the welfare of his crew. He took a great interest in his crew's exercise, was very careful about the quality of their food, and insisted upon the Bounty being kept very clean. His personal morals were above reproach. He cared about the natives of Tahiti, and tried (unsuccessfully) to check the spread of venereal disease among them. The flaw in this otherwise enlightened naval officer was, as J.C. Beaglehole wrote, " dogmatic judgements which he felt himself entitled to make; he saw fools about him too easily...thin-skinned vanity was his curse through life... never learnt that you do not make friends of men by insulting them."

On the Bounty's launch, with a hopeless journey ahead of him and obliged to navigate by memory, Bligh was in his element. In the face of disaster, his courage and leadership made him capable of great things. He could rally his crew around him, and save the lives of them all. It was routine circumstances in fair weather that caused his "thin-skinned vanity" to make him temperamental and acid-tongued. Bligh's tongue-lashings over petty matters were feared far more than his infrequent lashings with a whip.

Popular fiction often confuses Bligh with Edward Edwards of the Pandora, who was sent on the Royal Navy's expedition to find the mutineers and bring them to trial. Edwards was every bit the cruel man that Bligh was accused of being; the 14 men that he captured were confined in terrible conditions. When the Pandora ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef, 4 of the prisoners and 31 of the crew were killed. The prisoners would have all perished, had not some unknown crewman, more compassionate than Edwards, unlocked their cage before fleeing the doomed vessel.

In October 1790 Bligh was honourably acquitted at the court-martial inquiring the loss of the Bounty, shortly thereafter, A Narrative of the Mutiny on board His Majesty's Ship "Bounty" was published.

Of the 10 surviving prisoners, 4 were acquitted, due to Bligh's testimony that they were non-mutineers that Bligh was obliged to leave on the Bounty due to lack of space in the launch. Two others were convicted because, while not participating in the mutiny, they were passive and did not resist; they subsequently received royal pardons. One was convicted but excused on a technicality. The remaining three were convicted and hanged.

After the Bounty

After a court of inquiry, Bligh went on to serve under Admiral Nelson at the Battle of Copenhagen, commanding HMS Glatton, a 56-gun ship of the line, which was experimentally fitted exclusively with carronades. After the battle Bligh was personally praised by Nelson for his contribution to the victory. His navigational skills allowed him to navigate the Glatton safely between the banks while three other vessels ran aground. When Nelson feigned not to notice the signal 43 of Admiral Parker to stop the battle and kept the signal 16 hoisted to continue the engagement, Bligh on the Glatton was the only captain who could see the conflicting two signals. By choosing to display also the signal 16, Bligh ensured all the vessels behind the Glatton remained in the engagement.

As captain of HMS Director, at the Battle of Camperdown, Bligh engaged three Dutch vessels: the Haarlem, the Alkmaar and the Vrijheid. While the Dutch suffered serious casualties, on the Director only 7 seamen were wounded.

Bligh was offered the position of Governor of New South Wales by Sir Joseph Banks and appointed in March 1805, at £2,000 per annum, twice the rate of pay for the retiring Governor Philip Gidley King. He arrived in Sydney August 1806 to become the fourth governor of New South Wales. There he suffered another mutiny, the Rum Rebellion, when on 26 January 1808 the New South Wales Corps under orders of Major George Johnson (a.k.a. Johnston) marched on government house and arrested Governor Bligh. He sailed to Hobart on the 'Porpoise' and was welcomed by the Tasmanian Lieutenant-Governor David Collins, he remained on board and moored until January 1810. Effectively he was imprisoned (on board the 'Porpoise') from 1808 to 1810.

He sailed from Hobart and on 17 January 1810 he arrived in Sydney to collect evidence for the upcoming court-martial of Major George Johnson. He departed for the trial in England on 12th May and arrived in England on 25 October 1810 on board the 'Porpoise'. At the court-martial he was vindicated and George Johnson was cashiered from the Marine Corps and British armed forces.

In 1811, having been exonerated, he was promoted to Rear Admiral, and 3 years later, in 1814, promoted again, to Vice Admiral of the Blue.

Bligh designed the North Bull Wall at the mouth of the River Liffey in Dublin, to ensure the entrance to Dublin Port did not silt up and prevent a sandbar forming.

Bligh died in Bond Street, London on 6 December 1817 and was buried in a family plot at Lambeth. This church is now the Museum of Garden History. His gravestone is topped by a breadfruit. Bligh's house is marked by a plaque one block east of the Museum.

Sources

- Christopher Lloyd, St.Vincent & Camperdown, B.T. Batsford Ltd., London, 1963.

- Atlas of Maritime History. ISBN 0-8317-0485-3.

- G.P. Bom Hgz, D'VRIJHEID, Amsterdam, 1897.

- Gavin Kennedy, Bligh, Gerald Dockworth & Co. Ltd., 1978.

Further reading

- Alexander, Caroline. The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty, Viking Penguin, 2003, hardcover, 512 pages, ISBN 067003133X.

- Dening, Greg. Mr Bligh's Bad Language: passion, power and theatre on the Bounty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Reprinted 1994 in the Canto series, ISBN 0521467187.

- McKinney, Sam. Bligh: A True Account of the Mutiny Abord His Majesty's Ship Bounty', International Marine Publishing Company, 1989, hardcover, 210 pages, ISBN 0-87742-981-2.

- Mackaness, George. "The life of Vice-Admiral William Bligh, R.N., F.R.S." . Sydney, Angus and Robertson, .

External links

- A Voyage to the South Sea by William Bligh, 1792, from Project Gutenberg. The full title of Bligh's own account of the famous mutiny is: A Voyage to the South Sea, undertaken by command of His Majesty, for the purpose of conveying the bread-fruit tree to the West Indies, in his majesty's ship the Bounty, commanded by Lieutenant William Bligh. Including an account of the Mutiny on board the said ship, and the subsequent voyage of part of the crew, in the ship's boat, from Tofoa, one of the friendly islands, to Timor, a Dutch settlement in the East Indies. The whole illustrated with charts, etc.

- Works by William Bligh at Project Gutenberg

- Portraits of Bligh in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

- There is a display devoted to Bligh at the Museum of Garden History.

- Norfolk Island Your Island Home.

- Royal Naval Museum.

- The Saga of HMS Bounty and Pitcairn Island.

- The Extraordinary Life, Times and Travels of Vice-Admiral William Bligh. A major on-line biography of Bligh based around a dramatically illustrated graphic novel in ten chapters. Produced by Film Art Doco with assistance from the Australian Film Commission and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Free typeset PDF ebook of A Voyage to the South Sea, optimized for printing at home

| Preceded byPhilip Gidley King | Governor of New South Wales 1806-1808 |

Succeeded byLachlan Macquarie |