This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Bon courage (talk | contribs) at 07:11, 14 March 2015 (→Legislation and bans: better summary). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:11, 14 March 2015 by Bon courage (talk | contribs) (→Legislation and bans: better summary)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the food product made from liver. For the story by Isaac Asimov, see Pâté de Foie Gras (short story). "Fat liver" redirects here. For the medical condition, see Fatty liver.

Foie gras with mustard seeds and green onions in duck jus Foie gras with mustard seeds and green onions in duck jus | |

| Type | Spread |

|---|---|

| Main ingredients | Liver of a duck or goose |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,933 kJ (462 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbohydrates | 4.67 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 0.0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fat | 43.84 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protein | 11.40 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults, except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Foie gras (/ˌfwɑːˈɡrɑː/ , French for "fat liver") is a luxury food product made of the liver of a duck or goose that has been specially fattened. By French law, foie gras is defined as the liver of a duck or goose fattened by force-feeding corn with a feeding tube, a process also known as gavage. In Spain and other countries outside of France it is occasionally produced using natural feeding. Ducks are force-fed twice a day for 12.5 days and geese three times a day for around 17 days. Ducks are typically slaughtered at 100 days and geese at 112 days.

Foie gras is a popular and well-known delicacy in French cuisine. Its flavor is described as rich, buttery, and delicate, unlike that of an ordinary duck or goose liver. Foie gras is sold whole, or is prepared into mousse, parfait, or pâté, and may also be served as an accompaniment to another food item, such as steak. French law states that "Foie gras belongs to the protected cultural and gastronomical heritage of France."

The technique of gavage dates as far back as 2500 BC, when the ancient Egyptians began keeping birds for food and deliberately fattened the birds through force-feeding. Today, France is by far the largest producer and consumer of foie gras, though it is produced and consumed worldwide, particularly in other European nations, the United States, and China.

Gavage-based foie gras production is controversial due to the force-feeding procedure used. A number of countries and jurisdictions have laws against force-feeding, and the production, import or sale of foie gras; even where it is legal, a number of retailers decline to stock it.

History

Ancient times

As early as 2500 BC, the ancient Egyptians learned that many birds could be fattened through forced overfeeding and began this practice. Whether they particularly sought the fattened livers of birds as a delicacy remains undetermined. In the necropolis of Saqqara, in the tomb of Mereruka, an important royal official, there is a bas relief scene wherein workers grasp geese around the necks in order to push food down their throats. At the side stand tables piled with more food pellets, and a flask for moistening the feed before giving it to the geese.

The practice of goose fattening spread from Egypt to the Mediterranean. The earliest reference to fattened geese is from the 5th century BC Greek poet Cratinus, who wrote of geese-fatteners, yet Egypt maintained its reputation as the source for fattened geese. When the Spartan king Agesilaus visited Egypt in 361 BC, he noted Egyptian farmers' fattened geese and calves.

It was not until the Roman period, however, that foie gras is mentioned as a distinct food, which the Romans named iecur ficatum; iecur means liver and ficatum derives from ficus, meaning fig in Latin. The emperor Elagabalus fed his dogs on foie gras during the four years of his reign. Pliny the Elder (1st century AD) credits his contemporary, Roman gastronome Marcus Gavius Apicius, with feeding dried figs to geese in order to enlarge their livers:

"Apicius made the discovery, that we may employ the same artificial method of increasing the size of the liver of the sow, as of that of the goose; it consists in cramming them with dried figs, and when they are fat enough, they are drenched with wine mixed with honey, and immediately killed."

— Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book VIII. Chapter 77

Hence, the term iecur ficatum, fig-stuffed liver; feeding figs to enlarge a goose's liver may derive from Hellenistic Alexandria, since much of Roman luxury cuisine was of Greek inspiration. Ficatum was closely associated with animal liver and it became the root word for "liver" in each of these languages: foie in French, hígado in Spanish, fígado in Portuguese, fegato in Italian, fetge in Catalan and Occitan and ficat in Romanian, all meaning "liver"; this etymology has been explained in different manners.

Postclassical Europe

After the fall of the Roman empire, goose liver temporarily vanished from European cuisine. Some claim that Gallic farmers preserved the foie gras tradition until the rest of Europe rediscovered it centuries later, but the medieval French peasant's food animals were mainly pig and sheep. Others claim that the tradition was preserved by the Jews, who learned the method of enlarging a goose's liver during the Roman colonisation of Judea or earlier from Egyptians. The Jews carried this culinary knowledge as they migrated farther north and west to Europe.

The Judaic dietary law, Kashrut, forbade lard as a cooking medium, and butter, too, was proscribed as an alternative since Kashrut also prohibited mixing meat and dairy products. Jewish cuisine used olive oil in the Mediterranean, and sesame oil in Babylonia, but neither cooking medium was easily available in Western and Central Europe, so poultry fat (known in Yiddish as schmaltz), which could be abundantly produced by overfeeding geese, was substituted in their stead. The delicate taste of the goose's liver was soon appreciated; Hans Wilhelm Kirchhof of Kassel wrote in 1562 that the Jews raise fat geese and particularly love their livers. Some Rabbis were concerned that eating forcibly overfed geese violated Jewish food restrictions. The chasam sofer, Rabbi Moses Sofer, contended that it is not a forbidden food (treyf) as none of its limbs are damaged. This matter remained a debated topic in Jewish dietary law until the Jewish taste for goose liver declined in the 19th century. Another kashrut matter, still a problem today, is that even properly slaughtered and inspected meat must be drained of blood before being considered fit to eat. Usually, salting achieves that; however, as liver is regarded as "(almost) wholly blood", broiling is the only way of kashering. Properly broiling a foie gras while preserving its delicate taste is an arduous endeavour few engage in seriously. Even so, there are restaurants in Israel that offer grilled goose foie gras. Foie Gras also bears resemblance to the Jewish food staple, Chopped Liver.

Gentile gastronomes began appreciating fattened goose liver, which they could buy in the local Jewish ghetto of their cities. In 1570, Bartolomeo Scappi, chef de cuisine to Pope Pius V, published his cookbook Opera, wherein he describes that "the liver of domestic goose raised by the Jews is of extreme size and weighs two and three pounds." In 1581, Marx Rumpolt of Mainz, chef to several German nobles, published the massive cookbook Ein Neu Kochbuch, describing that the Jews of Bohemia produced livers weighing more than three pounds; he lists recipes for it—including one for goose liver mousse. János Keszei, chef to the court of Michael Apafi, the prince of Transylvania, included foie gras recipes in his 1680 cookbook A New Book About Cooking, instructing cooks to "envelop the goose liver in a calf's thin skin, bake it and prepare green or brown sauce to accompany it. I used goose liver fattened by Bohemian Jews, its weight was more than three pounds. You may also prepare a mush of it."

Production and sales

| This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (January 2015) |

| Country | Production

(tons, 2005) |

% of total

(2005) |

Production

(tons, 2014) |

% of total

(2014) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 18,450 | 78.5% | 18,750 | 78.5% |

| Hungary | 1,920 | 8.2% | 8.0% | |

| Bulgaria | 1,500 | 6.4% | 6.0% | |

| United States | 340 (2003) | 1.4% | 1.4% | |

| Canada | 200 (2005) | 0.9% | 1.0% | |

| China | 150 | 0.6% | 0.6% | |

| Others | 940 | 4.0% | ||

| Total | 23,500 | 100% |

Today, France is by far the largest producer and consumer of foie gras, though it is produced and consumed worldwide, particularly in other European nations, the United States, and China.

France is the leading producer and consumer of duck and goose foie gras. In 2005, the country produced 18,450 tonnes of foie gras (78.5% of the world's estimated total production of 23,500 tonnes) of which 96% was duck liver and the rest goose liver. Total French consumption of foie gras was 19,000 tonnes in 2005. Approximately 30,000 people are members of the French foie gras industry, with 90% of them residing in the Périgord (Dordogne), the Aquitaine régions in the southwest, and Alsace. The European Union recognizes the foie gras produced according to traditional farming methods (label rouge) in southwestern France with a geographical indication of provenance.

Hungary is the world's second-largest foie gras (libamáj) producer and the largest exporter (1,920 tonnes in 2005). France is the principal market for Hungarian foie gras; mainly exported raw. Approximately 30,000 Hungarian goose farmers are dependent on the foie gras industry. French food companies spice, process, and cook the foie gras so it may be sold as a French product in its domestic and export markets.

Bulgaria produced 1,500 tons of foie gras in 2005; The United States and Canada also have a thriving foie gras industry. The demand for foie gras in the Far East is such that China has become a sizeable producer. Madagascar is a small but rapidly growing producer of high quality foie gras.

Forms

In France, foie gras exists in different, legally defined presentations, from the expensive to the cheap:

- foie gras entier (whole foie gras), made of one or two whole liver lobes; either cuit (cooked), mi-cuit (semi-cooked), or frais (fresh);

- foie gras, made of pieces of livers reassembled together;

- bloc de foie gras, a fully cooked, moulded block composed of 98% or more foie gras; if termed avec morceaux ("with pieces"), it must contain at least 50% foie gras pieces for goose, and 30% for duck.

Additionally, there exist pâté de foie gras; mousse de foie gras (both must contain 50% or more foie gras); parfait de foie gras (must contain 75% or more foie gras); and other preparations (no legal obligation established).

Fully cooked preparations are generally sold in either glass containers or metal cans for long-term preservation. Whole, fresh foie gras is usually unavailable in France outside the Christmas period, except in some producers' markets in the producing regions. Frozen whole foie gras sometimes is sold in French supermarkets.

Whole foie gras is readily available from gourmet retailers in Canada, the United States, Hungary, Argentina and regions with a sizeable market for the product. In US, raw foie gras is classified as Grade A, B or C. Grade A is typically the highest in fat and especially suited for low-temperature preparation, because the veins are relatively few and the resulting terrine will be more aesthetically appealing because it displays little blood. Grade B is accepted for higher temperature preparation, because the higher proportion of protein gives the liver more structure after being seared. Grade C livers are generally reserved for making sauces as well as other preparations where a higher proportion of blood-filled veins will not impair the appearance of the dish.

Production methods

The physiological basis of foie gras production is the capacity some waterfowl have for weight gain, particularly in the liver, in preparation for migration. Toulouse geese and mulard ducks are the most commonly used breeds for foie gras. Mulards are a cross breed between a male Muscovy duck and a female Pekin duck, and are estimated to account for about 35% of all foie gras consumed in the US. It has been noted that the Muscovy duck is non-migratory, and both the Pekin and the mulard hybrid can not fly. Domestic ducks (including the Pekin) are derived from the mallard, which is sometimes migratory and sometimes not. Therefore, although the domestic goose might well be adapted to store food before migration, it is less likely that the Mulard hybrid has the same potential.

Typical foie gras production involves force-feeding birds more food than they would eat in the wild, and much more than they would voluntarily eat domestically. The feed, usually corn boiled with fat (to facilitate ingestion), deposits large amounts of fat in the liver, thereby producing the buttery consistency sought by the gastronome.

Physiology and preparation

Geese and ducks are omnivorous but unlike many birds, they lack a crop. The increasing amount of feed given prior to force-feeding and the force-feeding itself cause expansion of the lower part of the esophagus. In the wild this dilation allows them to swallow large foodstuffs, such as a whole fish, for a later, long digestion. Wild geese may consume 300 grams of protein and another 800 grams of grasses per day. Farmed geese allowed to graze on carrots adapt to eating 100 grams of protein, but may consume up to 2500 grams of the carrots per day. Force-feeding produces a liver that is six to ten times its ordinary size. Storage of fat in the liver produces steatosis of the liver cells.

The geese or ducks used in foie gras production are usually kept in a building on straw for the first four weeks, then kept outside for some weeks, feeding on grasses. This phase of the preparation is designed to take advantage of the natural dilation capacity of the esophagus. The birds are then brought inside for gradually longer periods while introduced to a high starch diet. The next feeding phase, which the French call gavage or finition d'engraissement, or "completion of fattening", involves forced daily ingestion of controlled amounts of feed for 12 to 15 days with ducks and for 15 to 18 days with geese. During this phase ducks are usually fed twice daily while geese are fed up to 4 times daily. In order to facilitate handling of ducks during gavage, these birds are typically housed in individual cages or small group pens during this phase.

Fattening

In modern production, the bird is typically fed a controlled amount of feed, depending on: the stage of the fattening process; its weight; and the amount of feed it last ingested. At the start of production, a bird might be fed a dry weight of 250 grams (9 oz) of food per day, and up to 1,000 grams (35 oz) (in dry weight) by the end of the process. The actual amount of food force-fed is much greater, since the birds are fed a mash whose composition is about 53% dry and 47% liquid (by weight).

The feed is administered using a funnel fitted with a long tube (20–30 cm long), which forces the feed into the animal's esophagus; if an auger is used, the feeding takes about 45 to 60 seconds. Modern systems usually use a tube fed by a pneumatic pump fed via a slit cut in the esophagus; with such a system the operation time per duck takes about 2 to 3 seconds. During feeding, efforts are made to avoid damaging the bird's esophagus, which could cause injury or death, although researchers have found evidence of inflammation of the walls of the proventriculus after the first session of force-feeding. There is also indication of inflammation of the esophagus in the later stages of fattening. Several studies have also demonstrated that mortality rates can be significantly elevated during the gavage period.

Ducks are typically slaughtered at 100 days of age and geese at 112 days.

Alternative production

Fattened liver can be produced by alternative methods without gavage, and this is referred to either as "fatty goose liver" or as foie gras (outside France), though it does not conform to the French legal definition, and there is debate about the quality of the liver produced. This method involves timing the slaughter to coincide with the winter migration, when livers are naturally fattened. This has only recently been produced commercially, and is a very small fraction of the market.

While force-feeding is required to meet the French legal definition of "foie gras", producers outside France do not always force-feed birds in order to produce fattened livers that they consider to be foie gras, instead allowing them to eat freely, termed ad libitum. Interest in alternative production methods has grown recently due to ethical concerns in gavage-based foie gras production. Such livers are alternatively termed fatty goose liver, ethical foie gras, or humane foie gras.

The term ethical foie gras or humane foie gras is also used for gavage-based foie gras production that is more concerned with the animal's welfare (using rubber hoses rather than steel pipes for feeding). Others have expressed skepticism at these claims of humane treatment, as earlier attempts to produce fattened livers without gavage have not produced satisfactory results.

More radical approaches have been studied. A duck or goose with a ventromedian hypothalamic (VMH) lesion will not tend to feel satiated after eating, and will therefore eat more than an unaffected animal. By producing such lesions surgically, it is possible to increase the animal's food consumption, when permitted to eat ad libitum, by a factor of more than two.

Preparations

Generally, French preparations of foie gras are over low heat, as fat melts faster from the traditional goose foie gras than the duck foie gras produced in most other parts of the world. American and other New World preparations, typically employing duck foie gras, have more recipes and dish preparations for serving foie gras hot, rather than cool or cold.

In Hungary, goose foie gras traditionally is fried in goose fat, which is then poured over the foie gras and left to cool; it is also eaten warm, after being fried or roasted, with some chefs smoking the foie gras over a cherry wood fire.

In other parts of the world foie gras is served in dishes such as foie gras sushi rolls, in various forms of pasta or alongside steak tartare or atop a steak as a garnish.

Cold preparations

Traditional low-heat cooking methods result in terrines, pâtés, parfaits, foams and mousses of foie gras, often flavored with truffle, mushrooms or brandy such as cognac or armagnac. These slow-cooked forms of foie gras are cooled and served at or below room temperature.

In a very traditional form of terrine, au torchon ("in a towel"), a whole lobe of foie is molded, wrapped in a towel and slow-cooked in a bain-marie. For added flavor (from the Maillard reaction), the liver may be seared briefly over a fire of grape vine clippings (sarments) before slow-cooking in a bain-marie; afterwards, it is pressed served cold, in slices.

Raw foie gras is also cured in salt ("cru au sel"), served slightly chilled.

A pastry containing fatty goose liver and other ingredients is known as the "Strasburg pie" since Strasbourg was a major producer of foie gras. The pie is mentioned in William Makepeace Thackeray's novel Vanity Fair as being popular with the diplomatic corps.

Hot preparations

Given the increased internationalization of cuisines and food supply, foie gras is increasingly found in hot preparations not only in the United States, but in France and elsewhere. Duck foie gras ("foie gras de canard") has slightly lower fat content and is generally more suitable in texture to cooking at high temperature than is goose foie gras ("foie gras d'oie"), but chefs have been able to cook goose foie gras employing similar techniques developed for duck, albeit with more care.

Raw foie gras can be roasted, sauteed, pan-seared (poêlé) or (with care and attention), grilled. As foie gras has high fat content, contact with heat needs to be brief and therefore at high temperature, lest it burn or melt. Optimal structural integrity for searing requires the foie gras to be cut to a thickness between 15 and 25 mm (½ – 1 inch), resulting in a rare, uncooked center. Some chefs prefer not to devein the foie gras, as the veins can help preserve the integrity of the fatty liver. It is increasingly common to sear the foie gras on one side only, leaving the other side uncooked. Practitioners of molecular gastronomy such as Heston Blumenthal of The Fat Duck restaurant first flash-freeze foie gras in liquid nitrogen as part of the preparation process.

Hot foie gras requires minimal spices; typically black pepper, paprika (in Hungary) and salt. Chefs have used fleur de sel as a gourmet seasoning for hot foie gras to add an "important textural accent" with its crunch.

Consumption

Foie gras is a regarded as a gourmet luxury dish. In France, it is mainly consumed on special occasions, such as Christmas or New Year's Eve réveillon dinners, though the recent increased availability of foie gras has made it a less exceptional dish. In some areas of France foie gras is eaten year-round.

Duck foie gras is the slightly cheaper and, since a change of production methods in the 1950s to battery, by far the most common kind, particularly in the US. The taste of duck foie gras is often referred to as musky with a subtle bitterness. Goose foie gras is noted for being less gamey and smoother, with a more delicate flavor.

Controversy

Gavage-based foie gras production is controversial due to the force-feeding procedure, the intensive housing and husbandry, the animal welfare consequences of an enlarged liver, and the potential for being detrimental to human health. One EU report states "Whilst studies of the anatomy of ducks and geese kept for foie gras production have been carried out, the amount of evidence in the scientific literature concerning the effects of force-feeding and liver hypertrophy on injury level, on the functioning of the various biological systems is small." This report, adopted on 16 December 1998, is an 89-page review of studies from several foie gras producing countries. It examines several indicators of animal welfare, including physiological indicators, liver pathology, and mortality rate. It strongly concludes that "force-feeding, as currently practised, is detrimental to the welfare of the birds."

Traditionally, foie gras was produced from special breeds of geese, however, more recently it is primarily produced from the hybrid male Mulard duck, a cross breeding between the male Muscovy duck and a female Pekin-type duck.

Force-feeding procedure

In modern gavage-based foie gras production, force-feeding takes place 17 to 30 days before slaughter. Geese and ducks show avoidance behaviour (indicating aversion) of the person who feeds them and the feeding procedure. Although an EU committee reported that there is no "conclusive" scientific evidence on the aversive nature of force-feeding and that evidence of injury is "small", in their overall recommendations they stated "the management and housing of the birds used for producing foie gras have a negative impact on their welfare". There is some inflammation of the esophagus in the later stages of force feeding.

The AVMA (Animal Welfare Division) when considering foie gras production stated "The relatively new Mulard breed used in foie gras production seems to be more prone than its parent breeds to fear of people..."

Housing and husbandry

During the force-feeding period, the birds are kept in individual cages, with wire or plastic mesh floors, or sometimes in small groups on slatted floors. Individual caging restricts movement by preventing the birds from standing erect, turning around, or flapping their wings. Birds cannot carry out other natural waterfowl behaviours, such as bathing and swimming.

Where ducks are fattened in group pens, it has been suggested that the increased effort required to capture and restrain ducks in pens might cause them to experience more stress during force feeding. Injuries and fatalities during transport and slaughter occur in all types of poultry production, however, fattened ducks are more susceptible to conditions such as heat stress. The relatively new Mulard breed used in foie gras production seems to be more prone to developing lesions in the area of the sternum when kept in small cages, and to bone breakage during transport and slaughter.

Animal rights and welfare advocates such as PETA, Viva!, and the Humane Society of the United States contend that foie gras production methods, and force-feeding in particular, constitute cruel and inhumane treatment of animals.

In April-May 2013, an investigator from Mercy for Animals recorded undercover video at Hudson Valley Foie Gras farm in New York state. The video showed workers forcefully pushing tubes down ducks' throats. One worker said of the force-feeding process: "Sometimes the duck doesn't get up and it dies. There have been times that 20 ducks were killed." Hudson Valley operations manager Marcus Henley replied that the farm's mortality statistics are not above average for the poultry industry. Because Hudson Valley provides foie gras to Amazon.com, Mercy for Animals began a campaign urging Amazon to stop selling foie gras, a move that has already been made by Costco, Safeway, and Target.

In November 2013, the Daily Mirror published a report based on the video they obtained depicting cruelty towards ducks in a farm owned by French firm Ernest Soulard, which is a supplier to celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay's restaurants. The restaurant chain suspended purchasing from the supplier following the exposé.

Enlarged liver

Another concern about foie gras production is the birds' livers being swollen. With increased food intake, fat may build up in the liver. In ducks, liver size changes seasonally, increasing by as much as 30 to 50%, with more pronounced changes in females. However, foie gras production enlargens the livers up to 10 times their normal size. This impairs liver function due to obstructing blood flow, and expands the abdomen making it difficult for the birds to breathe. Death occurs if the force-feeding is continued.

The mortality rate in force-fed birds varies from 2% to 4% during this period, compared with approximately 0.2% in age-matched, non-force-fed drakes.

Animal research

The process of force-feeding can make animals sick by stressing the liver. If the stress is prolonged, excess protein may build up and clump together as amyloids, consumption of which has been found to induce amyloidosis in laboratory mice. It has been hypothesized this may be a route of transmission in humans too and so be a risk for people with inflammatory complaints such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Legislation and bans

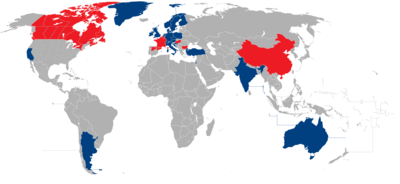

Further information: Foie gras controversy § Statutory and voluntary bansA number of countries and regions have laws against force-feeding or the sale or importation of foie gras, and even where it it legal some retailers have ceased to sell it.

See also

- Shen Dzu – the fattening of pigs in manner similar to gavage

- List of delicacies

- Specialty foods

Notes

- United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- French rural code Code rural - Article L654-27-1: Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("'Foie gras' is understood to mean the liver of a duck or a goose that has been specially fattened by gavage, also served with toast").

- The Perennial Plate: Episode 121: A Time for Foie. . June 2013.

- Ted Talks: Dan Barber's foie gras parable. . July 2008.

- ^ "Torture in a tin: Viva! foie-gras fact sheet" (PDF). Viva!. 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- French rural code L654-27-1

- "Ancient Egypt: Farmed and domesticated animals".

- ^ A Global Taste Test of Foie Gras and Truffles : NPR

- (McGee 2004, p. 167): "Foie gras is the "fat liver" of force-fed geese and ducks. It has been made and appreciated since Roman times and probably long before; the force-feeding of geese is clearly represented in Egyptian art from 2500 BC."

- ^ (Toussaint-Samat 1994, p. 425).

- (Ginor 1999, p. 2).

- "Saudi Aramco World : Living With the Animals".

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 21 (help) - ^ (Alford 2001, p. 36).

- (Ginor 1999, p. 3).

- Authentic Recipes, Food, Drinks, and Cooking Techniques

- (Ginor 1999, p. 4).

- (Giacosa 1994, p. 13).

- (Langslow 2000, p. 153): "A second instance of the restriction of the sense of a Latin anatomical term to animals is iecur 'the liver' in Theodorus and Cassius. In both, the human liver is always hepar, while iecur is used of an animal (...)"

- "Ficus,i" (...) Derivés: (...) ficatum n. (sc. iecur): d'abord terme de cuisine "foie garni de figues", cf. Hor., S. 2, 8, 88, ficis pastum iecur anseris albae, calque du gr. συκωτόν de même sens, puis, dans le langage populaire, simplement "foie" (...) et passé avec ce sens dans les langues romanes, où ficatum a remplacé iecur. A. Ernout, A. Meillet, Dictionnaire etymologique de la langue latine, Éd. Klincksieck, Paris 1979.

- (Toussaint-Samat 1994, p. 426).

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History (eds. John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley). For the original Latin text, see here. The Latin text (ed. Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff) of Perseus Digital Library places the corresponding text in a wrong chapter. URL accessed December 30, 2006.

- (Faas 2002, p. 19)

- Malkiel, Yakov (1944). "The Etymology of Portuguese Iguaria". Language. 20 (3): 108–30. JSTOR 410151.

- (Walter 2006, p. 40): "(...) for example, why it is not the word JECUR (a Latin word taken from the Greek) which has come down to us with the meaning of 'liver', but the Romance word ficato, which has become the French foie. The word ficato is formed on the Latin word FICUS 'fig', and would appear to have nothing to do with the 'liver' other than the Greeks, followed by the Romans, fattened their geese with figs to obtain particularly fleshy and tasty livers. The FICATUM JECUR or 'fig-fattened goose liver', which was very much sought after, must have become such a common expression that it was shortened to FICATUM (just as the modern French say frites as an abbreviation of pommes de terre frites). To begin with the word FICATUM probably designated only edible animal livers, with its meaning then being extended to include the human organ."

- (Littré 1863, p. 137): "Feûte n'est pas mieux fait que foie; seulement, il conserve le t du Latin; car on sait que foie vient de ficatum (foie d'une oie nourrie de figues, et, de là, foie en général). Foie en français, feûte en wallon, fetge en provençal, fégato en italien, hígado en espagnol, fígado en portugais, témoignent que la bouche romane déplaça l'accent du mot Latin, et, au lieu de ficátum, qui est la prononciation régulière, dit, par anomalie, fícatum avec l'accent sur l'antépénultième."

- Dizionario etimologico online: fégato.

- (Ginor 1999, p. 8).

- ^ (Ginor 1999, p. 9).

- (Davidson 1999, p. 311): "The enlarged liver has been counted a delicacy since classical times, when the force-feeding of the birds was practised in classical Rome. It is commonly said that the practice dates back even further, to ancient Egypt, and that knowledge of it was possibly acquired by the Jews during their period of 'bondage' there and transmitted by them to the classical civilizations."

- (Alford 2001, p. 37).

- ^ Eileen Lavine. "Foie Gras: The Indelicate Delicacy". Moment Magazine.

- ^ (Ginor 1999, p. 11).

- (Toussaint-Samat 1994, p. 427).

- ^ "China to boost foie gras production". Xinhua online. 11 April 2006. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- "Foie Gras Food Debate on StarChefs".

- http://www.mapaq.gouv.qc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/A8B635A2-01C6-40B1-8CE3-B628A2C17F2F/5950/Bioclips13n18.pdf

- http://www.itavi.asso.fr/economie/eco_filiere/NoteConjonctureFoieGras.pdf

- http://www.mensvogue.com/food/articles/2006/08/21/foie_gras?currentPage=1

- "Prohibido el foie gras en California". PACMA.

- "Food Ingredients & Food Science - Additives, Flavours, Starch". FoodNavigator.com.

- Thorpe, Nick (12 January 2004). "Hungary foie gras farms under threat". BBC News. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Rakotomalala, M. Élevage - La filière foie gras se porte bien. Express de Madagascar. No. 5632. 15 May 2013.

- Decree 93-999 August 9, 1993 defining legal categories and terms for foie gras in France

- Template:PDFlink, section 4

- Toulouse Goose Pyrenees Biological Academy (in French)

- Ravo, Nick (24 September 1998). "A Cornucopia of Native Foie Gras; Partners' Efforts Produce Menu Delicacy in Abundance". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Hoffmann, E. (1992). "A natural history of Cairina moschata, the wild Muscovy duck". 9th International Symposium of Waterfowl. Pisa, Italy: World Poultry Association.: 217–219.

- Hoffmann, E. (1992). "Hybrid progeny from Muscovy and domestic ducks". 9th International Symposium of Waterfowl. Pisa, Italy: World Poultry Association.: 64–66.

- ^ Template:PDFlink

- http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/welfare/international/out17_en.pdf Report of the Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare, Chapter 4, pp 24–29

- ^ Skippon, W. (2013). "The animal health and welfare consequences of foie gras production". Canadian Veterinary Journal. 54 (4): 403–404. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Template:PDFlink, p60

- Template:PDFlink EU Scientific Report, p19

- tours.inra.fr

- Guémené, D.; Guy, G.; Noirault, J.; Garreau-Mills, M.; Gouraud, P.; Faure, J.M. (2001). "Force-feeding procedure and physiological indicators of stress in male mule ducks". British Poultry Science. 42 (5): 650–7. doi:10.1080/00071660120088489. PMID 11811918.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - The standard practice is pneumatic force-feeding, as stated on this page and this foie gras enthusiast page; see also this force-feeding equipment page.

- Serviere, J, Bernadet, MD and Guy, G. 2003. Is nociception a sensory component associated to force-feeding? Neurophysiological approach in the mule duck. 2nd World Waterfowl Conference. Alexandria, Egypt

- Foie Gras Production Backgrounder

- EU Report

- Koehl, PF and Chinzi, D. 1996. Les resultats technico-economiques des ateliers de palmidpedes a foie gras de 1987 a 1994. 2eme journees de la recherche sur les palmipedes a foie gras. 75.

- Chinzi, D and Koehl, PF. 1998. Caracteristiques desateliers d'elevage et de gavage de canards et mulards. Relations avec les performances et techniques et economiques. Proceedings des 3eme journees de la recherche sur les palmipedes a foie gras. 107.

- "Login".

- Glass, Jliet (25 April 2007). "Foie Gras Makers Struggle to Please Critics and Chefs". New York Times.

- Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare (1998). "Alternative Methods of Production". Welfare Aspects of the Production of Foie Gras in Ducks and Geese. Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 57.

- Felix, Bernadette; Auffray, P.; Marcilloux, J. C.; Royer, L. (1980). "Effect of induced hypothalamic hyperphagia and forced-feeding on organ weight and tissular development in Landes geese". Reproduction Nutrition Développement. 20 (3A): 709–17. doi:10.1051/rnd:19800413. PMID 6961479.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Au Pied de Cochon. Menu. Montreal. 15 June. 2006.

- The New Encyclopædia, ed. Daniel Coit Gilman, Harry Thurston Peck and Frank Moore. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1903): Vol. XIII, 778.

- William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair, Ch. 9.

- Schwartzkoff, Louise (2 February 2010). "Books – The Fat Duck Cookbook by Heston Blumenthal". Sydney Morning Herald (Book review).

- Nation's Restaurant News, 2004.

- Serventi 1993, cover text.

- ^ "The goose is getting fat Politically incorrect it may be, but foie gras is storming British menus. Anwer Bati reports". The Daily Telegraph. London. 1 November 2003. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ... goose liver is more delicate and less gamey tasting that its duck equivalent France: World Food By Stephen Fallon, Michael Rothschild ISBN 1-86450-021-2, ISBN 978-1-86450-021-9 page 49

- ^ "Welfare Implications of Foie Gras Production". American Veterinary Medical Association. 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Foie Gras: Delicacy of Despair

- Viva! – Vegetarians International Voice for Animals

- Foie Gras

- Tepper, Rachel (12 June 2013). "Undercover Foie Gras Footage Shot At Hudson Valley Foie Gras Alleges Cruel Practices (VIDEO)". Huffington Post. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Zara, Christopher (12 June 2013). "Amazon Urged To Ban Foie Gras: Animal-Rights Group Calls Retailer A Lame Duck Over Controversial Food". International Business Times. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Andy Lines (8 November 2013). "VIDEO: Cruelty of chef Gordon Ramsay's foie gras supplier exposed in shocking footage". mirror.

- Westermark, Gunilla T.; Westermark, Per (2010). "Prion-like aggregates: Infectious agents in human disease". Trends in Molecular Medicine (Review). 16 (11): 501–7. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2010.08.004. PMID 20870462.

AA amyloidosis can theoretically be transmitted to humans by the same route; thus, such food might constitute a hazard for individuals with chronic inflammatory disorders such as RA.

- "Amazon bans foie gras". The Bugle (requires free account to view). 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Fortnum and Mason faces celebrity battle over its sale of 'cruel' foie gras". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Harvey Nichols bans 'cruel' pate". BBC. 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

References

- Books

- Larousse Gastronomique, by Prosper Montagne (Ed.), Clarkson Potter, 2001. ISBN 0-609-60971-8.

- Alford, Katherine (2001). Caviar, Truffles, and Foie Gras. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2791-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Bett, Henry (2003). Wanderings Among Words. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7792-0Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211579-0Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Faas, Patrick (2002). Around the Table of the Romans: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23958-0Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Giacosa, Ilaria Gozzini (1994). A Taste of Ancient Rome. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-29032-8Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Ginor, Michael A. (1999). Foie Gras: A Passion. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-29318-0Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Langslow, David R. (2000). Medical Latin in the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815279-5Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Littré, Maximilien Paul Emile (1863). "Histoire de la langue française: Études sur les origines, l'étymologie, la grammaire". DidierTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner. ISBN 0-684-80001-2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Serventi, Silvano (1993). La grande histoire du foie gras. Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-200542-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne (1994). History of Food. Blackwell Publishing Professional. ISBN 0-631-19497-5Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Walter, Henriette (2006). French Inside Out: The French Language Past and Present. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07670-6Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link).

- Articles

- Fabricant, Florence (2004). "Peppering with salt: chefs find favor with gourmet versions of common seasoning". Nation's Restaurant News. 38 (9): 36.

External links

Video of foie gras production.

Scientific studies

- Report of the EU Scientific Template:PDFlink

Alternatives

- Foie Gras without force-feeding

- Faux Gras – "Foie Gras Without The Cruelty"

- Chef Dan Barber tells the story of a small farm in Spain that has found a humane way to produce foie gras

- Can Ethical Foie Gras Happen in America? TIME, 12 August 2009