This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Etamni (talk | contribs) at 08:37, 10 September 2015 (→top: changed link to "sex offender registry" to the US-centric version of this article because this is a US law with no application outside of the US). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:37, 10 September 2015 by Etamni (talk | contribs) (→top: changed link to "sex offender registry" to the US-centric version of this article because this is a US law with no application outside of the US)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| |

| Long title | An Act to protect children from sexual exploitation and violent crime, to prevent child abuse and child pornography, to promote internet safety, and to honor the memory of Adam Walsh and other child crime victims. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 109th United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 109-248 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 42 |

| U.S.C. sections created | § 16911 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| United States v. Comstock, 560 U.S. ___ (2010); United States v. Kebodeaux, 570 U.S. ___ (2013) | |

The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act is a federal statute that was signed into law by U.S. President George W. Bush on July 27, 2006. The Walsh Act organizes sex offenders into three tiers according to the crime committed, and mandates that Tier 3 offenders (the most serious tier) update their whereabouts every three months with lifetime registration requirements. Tier 2 offenders must update their whereabouts every six months with 25 years of registration, and Tier 1 offenders must update their whereabouts every year with 15 years of registration. Failure to register and update information is a felony under the law. States are required to publicly disclose information of Tier 2 and Tier 3 offenders, at minimum. It also contains civil commitment provisions for sexually dangerous persons.

The Act also creates a national sex offender registry and instructs each state and territory to apply identical criteria for posting offender data on the internet (i.e., offender's name, address, date of birth, place of employment, photograph, etc.). The Act was named after Adam Walsh, an American boy who was abducted from a Florida shopping mall and later found murdered.

As of April 2014, the Justice Department reports that 17 states, three territories and 63 tribes had substantially implemented requirements of the Adam Walsh Act.

History

The Adam Walsh Act emerged from Congress following the passage of separate bills in the House and Senate (H.R. 3132 and S. 1086 respectively). The Act is also known as the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA), the majority of the provisions of which were enacted as 42 U.S.C. §16911 et seq. The act’s provisions fall into four categories: a revised sex offender registration system, child and sex related amendments to federal criminal and procedure, child protective grant programs, and other initiatives designed to prevent and punish sex offenders and those who victimize children.

The sex offender registration provisions replace the Jacob Wetterling Act provisions with a statutory scheme under which states are required to modify their registration systems in accordance with federal requirements at the risk of losing 10% of their Byrne program law enforcement assistance funds. The act seeks to close gaps in the prior system, provide more information on a wider range of offenders, and make the information more readily available to the public and law enforcement officials.

In the area of federal criminal law and procedure, the act enlarges the kidnapping statute, increases the number of federal capital offenses, enhances the mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment and other penalties that attend various federal sex offenses, establishes a civil commitment procedure for federal sex offenders, authorizes random searches as a condition for sex offender probation and supervised release, outlaws internet date drug trafficking, permits the victims of state crimes to participate in related federal habeas corpus proceedings, and eliminates the statute of limitations for certain sex offenses and crimes committed against children.

The act revives the authorization of appropriations under the Police Athletic Youth Enrichment Act among its other grant provisions and requires the establishment of a national child abuse registry among its other child safety initiatives.

The Act also establishes a post-conviction civil commitment scheme. Section 4248 of the Act contains the Commitment Provision, which authorizes the federal government to initiate commitment proceedings with respect to any federal prisoner in the custody of the Bureau of Prisons. Under this provision, even prisoners who have never been previously charged with or convicted of a sex crime may be civilly committed after completing their entire prison sentence. Prior to Supreme Court Review, the federal Circuit courts were split on the question of whether Congress had the authority to enact this provision. On May 17, 2010, the Supreme Court upheld the law, and ruled in United States v. Comstock that the Civil Commitment Provision was within Congress‘s authority.

At the time of passage, at least 100,000 of more than a half million sex offenders in the United States and the District of Columbia were 'missing' and unregistered as required by law. The act allocated federal funding was to assist states in maintaining and improving these programs so a comprehensive system for tracking sex offenders and alerting communities would be developed.

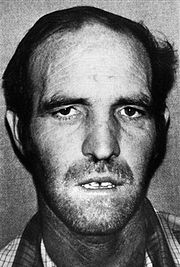

The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act was signed on the 25th anniversary of the abduction of Adam Walsh from a shopping mall in Florida. Adam Walsh was found murdered 16 days after his abduction in 1981, and the perpetrator was not named until December 16, 2008, when the Hollywood, Florida police department announced that they had evidence that Ottis Toole was the killer. Adam Walsh's father is John Walsh, host of the television series America's Most Wanted. John Walsh, also founder of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), was joined by other children's advocates to mount an aggressive campaign to get the bill passed into law. As part of the campaign, Walsh was joined by Congressman Sensenbrenner, representatives from the NCMEC, and other victims' advocates and parents. These included Patty Wetterling, children's advocate from Minnesota and mother of missing child Jacob Wetterling, abducted in October 1989; Mark Lunsford, whose daughter Jessica was killed in Florida in 2005; Linda Walker, the mother of North Dakota college student Dru Sjodin who was kidnapped and murdered by a released Minnesota sex offender in November 2003; and Erin Runnion, whose five-year-old daughter Samantha Runnion was raped and killed in California in 2002.

Legal applications

- Gives the U.S. Attorney General the authority to apply the law retroactively

- Gives a federal Judge the ability to civilly commit individuals who are in the custody of the federal prison system if it is proven that the individual (1) has engaged or attempted to engage in sexually violent conduct or child molestation; (2) suffers from a serious mental illness, abnormality, or disorder; and, (3) as a result, would have serious difficulty refraining from sexually violent conduct or child molestation if released. A hearing is available to the involuntarily committed individual every six months to reconsider their commitment status if requested by counsel or the person in the federal treatment program.

- Establishes a national database which will incorporate the use of DNA evidence collection and DNA registry and tracking of convicted sex offenders with Global Positioning System technology.

- The law defines and requires a three-tier classification system for sex offenders, based on offense committed, replacing the older system based on risk of re-offence.

- Tier 1 sex offenders are required to register for 10–15 years; tier 2 for 25 years and tier 3 offenders must register for 25 years to life.

- Increases the mandatory minimum incarceration period of 25 years for kidnapping or maiming a child and 30 years for sex with a child younger than 12 or for sexually assaulting a child between 13 and 17 years old.

- Increases the penalties for sex trafficking of children and child prostitution.

- Widens federal funding to assist local law enforcement in tracking sexual exploitation of minors on the internet.

- Creates a national child abuse/neglect registry to protect children from being placed into the care of or adopted by people convicted of child abuse or child neglect.

- Limits the defense access to examine child exploitation material which is the subject of a charge, such that examination may only be conducted in a government building.

Registration requirements

The required retroactive application of requirements will be defined solely by conviction offense, not by severity or risk of re-offense, nor will it differentiate between violent or nonviolent offenses. For example, a Tier 3 sex offender who was released from imprisonment for such an offense in 1930 will still have to register for the remainder of his or her life. A Tier 2 sex offender convicted in 1980 is already more than 25 years out from the time of release. A Tier 1 will have to register for 10–15 years. In such cases, a jurisdiction may credit the sex offender with the time elapsed from his or her release.

Children 14 years of age or older at the time of offense are required to register only if they fit into the third (most serious) tier or were tried as adults. Such juveniles will be subject to all the same registration requirements as other Tier 3 offenders.

Effects

In some states the Adam Walsh Act (AWA) effectively expanded the registries as much as 500%. Since its enactment, critics have expressed concerns about the act's scope and breadth. Several sex offenders were prosecuted under its regulations before any state adopted AWA. This has resulted in one life sentence for failure to register, due to the offender being homeless and not being able to maintain a physical address. The Adam Walsh Act requires anyone convicted of a sex crime to register as a sex offender where it will be posted on the internet for all to see.

Study conducted in Ohio found that retroactive AWA re-classification increased the number of offenders and altered their placement in management categories. Prior implementation of AWA in Ohio 76% of adult and 88% of juvenile offenders were designated on least restrictive category or had not to register at all, while only 20% of adults and 5% of juveniles were classified as "sexual predators", the most restrictive category. Following re-classification this basic pattern was reversed, with 13% of adults and 22% of juveniles placed in Tier 1, 31% of adults and 32% of juveniles placed in Tier 2, and 55% of adults and 46% of juveniles placed in the highest and most restrictive Tier 3. 41% of adults and 43% of juveniles previously in lowest category and 59% of adults and 45% of juveniles who were not previously registered at all were assigned to Tier 3.

State implementation

As of 2014, 17 of 50 states have substantially implemented minimum requirements set forth in the Adam Walsh Act's Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA). Study published in 2009 surveying 35 states, identified multiple areas of concern relating to legal, operational, financial and practical domains that have precluded (or may preclude) some states from undertaking the necessary revisions to achieve compliance with SORNA.

Legal barriers

Study found states' concerns over actual or potential legal impediments to SORNA implementation to be prominent across multiple provision areas. Three of these areas — the expansion of covered offenses, the inclusion of certain classes of juveniles and the re-classification of individuals into offense-based tiers were found to be problematic to states, as they directly relate to increasing the number of individuals subject to registration and/or public notification. This, in turn, was found to cause concern among states regarding conflicts with state constitutional provisions and with potential federal and state legal challenges related to alleged ex post facto, equal protection, and due process violations. One responding state moving towards compliance with SORNA reported expecting “a severe legal backlash” from making the changes apply retroactively.

Operational barriers

Study found that respondents — particularly those directly involved in their state registration systems — expressed concern regarding potentially significant operational impediments in several provision areas. One particularly prominent operational concern involved states’ lack of capacity to adapt to SORNA’s retroactivity provisions, specifically those requiring the identification and registration of individuals who enter the criminal justice system on a nonsexual offense, but who had previous sexual offense convictions or adjudications. Several states provided comments indicating that such information is not readily available within their information systems, making compliance particularly problematic.

Other areas of operational concern relate to the demands associated with transitioning from risk-based to offense-based systems, information technology enhancements related to expanded data requirements, and the adaptation of registration update systems and personnel to respond to increased workloads.

Financial barriers

Several of surveyed states noted that they had completed fiscal analyses that identified a range of SORNA-related costs including system development, reclassification, expanded enforcement personnel, judicial and correctional costs, and legal costs related to prosecution, defense, and potential litigation on constitutional grounds. While jurisdictions remain eligible to cover some initial start-up costs through Department of Justice grant programs authorized by AWA, state analyses have suggested substantial ongoing operational costs, primarily local law enforcement-related expenses associated with expanding the number of registrants and the expansion of reporting requirements. Commenting on an anticipated expansion of the number of offenders in the higher tiers, one registry official indicated that “sheriff’s departments will not be able to cope with the increased burden, and with no funding available it is likely that offenders will become non-compliant on a massive scale.”

Practical barriers

Responding states were asked to evaluate the potential adverse public safety impacts of modifying their existing state policies to meet SORNA requirements. Two provision areas emerged as particularly problematic — the inclusion of adjudicated juveniles and the requirements for offense-based classification. Regarding the former, states expressed concern that registration of and notification on juveniles undermines the concepts of juvenile justice and significantly compromises the potential for these youth to effectively integrate into society.

As for the latter, states differentiating registration and notification levels according to standardized and empirically validated risk assessment instruments have expressed significant concern that differentiating offenders based solely on the crime of conviction dramatically compromises the ability to focus enforcement resources on the most dangerous offenders.

Influence on visa process

A collateral effect of the new legislation was its implications on the United States Permanent Resident Card process. Until January 2007, U.S. nationals living abroad who married a local and intended to obtain green cards for their spouse and any immediate family members were able to initiate and complete the majority of the application process at the local U.S. Embassy/Consulate. However, because of the newly enhanced background check and criminal history data trail requirements, the new law had initially been interpreted by the Bureau of Consular Affairs and USCIS as leaving Consular officers ill-equipped to fully handle the I-130 adjucation process. Thus, as of January 2007, I-130 petitions, supporting documentation, or fee payments could no longer be completed in the country of the foreign national.

However, the government made a quick about-face two months later. Due to a significant number of complaints from applicants about the resultant processing delays and from immigration officials about the deluge of paperwork that came with the centralization of the process, the visa petitioning process for immediate relatives of US citizens was resumed at U.S. embassies on March 21, 2007. However, all embassies were required to add a 6-month residency requirement for the US Citizen to file an application directly.

The Act also for the first time limits the rights of citizens or permanent residents to petition to immigrate their spouse or other relatives to the U.S. if the petitioner has a listed child sex abuse conviction. If that is the case, then the petition cannot be approved unless the Department of Homeland Security determines in its unreviewable discretion that there is no risk of harm to the beneficiary or derivative beneficiary.

The Federal Record Keeping and Labeling Requirements Laws have been attached to this bill (18 USC 2257). This will require secondary producers to be responsible for the record keeping procedures primary producers gather when they produce pornography.

See also

- National Center for Missing and Exploited Children

- Senate Caucus on Missing, Exploited and Runaway Children

- House Caucus on Missing and Exploited Children

References

- ^ Pub. L. 109–248 (text) (PDF)

- ^ Barker, The Adam Walsh Act: Un-civil Commitment, available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1496934#

- "President Signs H.R. 4472, the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006". White House. 2006. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- "Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act Compliance News". National Conference of State Legislatures.

- 42 U.S.C. 16925

- United States v. Comstock, 551 F.3d 274 (4th Cir. 2009), cert. granted, 129 S.Ct. 2828 (U.S. June 22, 2009/Decided May 17, 2010) (No. 08-1224).

- ^ Davidson, Lee (2006). "Bush signs, Hatch praises new Child Protection Act". Deseret Morning News. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - 42 USC 16915

- "H.R. 4472 — Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006" (PDF). Legislative Notice. U.S. Senate Republican Policy Committee. 2006. Archived from the original (pdf) on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "5 years later, states struggle to comply with federal sex offender law". CNN. July 28, 2011.

- Dewan, Shaila (August 3, 2007). "Homelessness Could Mean Life in Prison for Offender". The New York Times.

- Harris, A. J.; Lobanov-Rostovsky, C.; Levenson, J. S. (April 2, 2010). "Widening the Net: The Effects of Transitioning to the Adam Walsh Act's Federally Mandated Sex Offender Classification System". Criminal Justice and Behavior. 37 (5): 503–519. doi:10.1177/0093854810363889.

- ^ Harris, A. J.; Lobanov-Rostovsky, C. (September 22, 2009). "Implementing the Adam Walsh Act's Sex Offender Registration and Notification Provisions: A Survey of the States" (PDF). Criminal Justice Policy Review. 21 (2): 202–222. doi:10.1177/0887403409346118.

- "I-130, Petition for Alien Relative" (PDF). Department of Homeland Security U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Archived from the original (pdf) on June 29, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Consular Offices Abroad Resume Accepting I-130 Immigrant Visa Petitions". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on June 16, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Free Speech Coalition v. Gonzales (2005)". Free Speech Coalition. Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Lara Geer Farley, The Adam Walsh Act: The Scarlet Letter of the Twenty-First Century, Washburn Law Journal, vol. 47, pp. 471–503

External links

- Sex Crimes Blog: Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act Resource Page

- The Scarlet Letter of the Law: The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006

- The Adam Walsh Act: Un-civil Commitment