This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Leoboudv (talk | contribs) at 06:07, 9 December 2015 (→Architecture). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 06:07, 9 December 2015 by Leoboudv (talk | contribs) (→Architecture)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

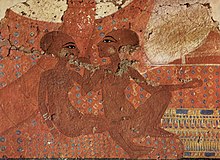

The Ancient Egyptian art style, known as Amarna Art or the Amarna Style, is a style which was adopted in the Amarna Period (i.e. during and just after the reign of Akhenaten in the late Eighteenth Dynasty), and is noticeably different from more conventional Egyptian art styles.

Historians believe that Amenhotep IV may have been one of the first to practice monotheism, the belief in just one god. Shortly after claiming the throne, he declared the god Aten, represented by the sun, was the only true god. To pay homage to his chosen god, Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akenaten. Throughout his rule, Akenaten changed many aspects of Egyptian culture to celebrate or praise his singular god, especially the style and usage of art.

The introduction of Amarna art was a period of great transition within Egyptian Art. It is characterized by a sense of movement and activity in images, with figures having raised heads, many figures overlapping and many scenes busy and crowded. Also, the human body is portrayed differently in Amarna artwork than in Egyptian art as a whole. One of the greatest changes to traditional Egyptian art within the Amarna period was the depiction of the human figure within the artwork. For instance, many depictions of Akhenaten's body give him distinctly feminine qualities such as large hips, prominent breasts, and a larger stomach and thighs. This is a divergence from the earlier Egyptian art which shows men with perfectly chiseled bodies. Faces on reliefs are still shown exclusively in profile.

The illustration of figures' hands and feet are apparently important. Fingers and toes are depicted as long and slender and are carefully detailed to show nails. Artists also showed subjects with elongated facial structures accompanied by folds within the skin as well as lowered eyelids. The figure was also illustrated with a more elongated body than the previous representation. In the new human form, the subject had more fat in the stomach, thigh, and breast region, while the torso, arm, and legs were thin and long like the rest of the body. The skin color of both male and female is generally dark brown (contrasted with the usual dark brown or red for males and light brown or white for females) – this could merely be convention, or it may depict the ‘life’ blood. Figures in this style are shown with both a left and a right foot, contrasting the traditional style of being shown with either two left or two right feet.

Tombs

The decoration of the tombs of non-royals is quite different from previous eras. These tombs do not feature any funerary or agricultural scenes, nor do they include the tomb occupant unless he or she is depicted with a member of the royal family. There is an absence of other gods and goddesses, apart from the Aten, the sundisc. However, the Aten does not shine its rays on the tomb owner, only on members of the royal family. There is neither a mention of Osiris nor other funerary figures. There is also no mention of a journey through the underworld. Instead, excerpts from the Hymn to the Aten are generally present.

Sculpture

Sculptures from the Amarna period are set apart from other periods of Egyptian art. One reason for this is the accentuation of certain features. For instance, an elongation and narrowing of the neck and head, sloping of the forehead and nose, a prominent chin, large ears and lips,spindle-like arms and calves as well as large thighs, stomachs, and hips were often portrayed.

In a relief of Akhenaten, he is portrayed with his primary wife, Nefertiti, and their children, the six princesses, in an intimate setting. His children appear to be fully grown, only shrunken to appear smaller than their parents, a routine stylistic feature of traditional Egyptian art. They also have elongated necks and bodies. An unfinished head of a princess from this time, in the Tutankhamun, and the golden age of the pharaohs exhibition, displays a very prominent elongation to the back of the head.

The unusual, elongated skull shape often used in portrayal of the royal family "may be a slightly exaggerated treatment of a hereditary trait of the Amarna royal family", according to the Brooklyn Museum, seeing as "the mummy of Tutankhamun, presumed to be related to Akhenaten, has a similarly shaped skull, although not so elongated as ". However, there is still a possibility the style is purely ritualistic.

The hands at the end of each ray extending from Aten in the relief are delivering the ankh, which symbolized "life" in the Egyptian culture, to Akhenaten and Nefertiti and often also reach the portrayed princesses. The importance of the Sun God Aten is central to much of the Amarna period art, largely because Akhenaten's rule was marked by its monotheistic following of Aten.

In several, if not most sculptures of Akhenaten, he has wide hips and a visible paunch. His lips are thick and his arms and legs are thin and lack muscular tone, unlike his counterparts of other eras in Egyptian artwork. Some scholars suggest that the presentation of the human body as imperfect during the Amarna period is in deference to Aten. Others think Akhenaten suffered from a genetic disorder (most likely the product of inbreeding) that caused him to look as such. Others interpret this unprecedented stylistic break from Egyptian tradition to be a reflection of the Amarna Royals' attempts to wrest political power from the traditional priesthoods and bureaucratic authorities.

Much of the finest work, including the famous Nefertiti bust in Berlin, was found in the studio of the second and last Royal Court Sculptor Thutmose, and is now in Berlin and Cairo, with some in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The period saw the use of sunk relief, previously used for large external reliefs, extended to small carvings, and used for most monumental reliefs. Sunk relief appears best in strong sunlight. This was one innovation that had a lasting effect, as raised relief is rare in later periods.

Architecture

Not many buildings from this period have survived the ravages of later kings, partially as they were constructed out of standard size blocks, known as talatat, which were very easy to remove and reuse. In recent decades, re-building work on later buildings has revealed large number of reused blocks from the period, with the original carved faces turned inwards, greatly increasing the amount of work known from the period.

Temples in Amarna did not follow the traditional Egyptian design and were smaller, with sanctuaries open to the sun, containing large numbers of altars. They had no closing doors. See Great Temple of the Aten, Small Temple of the Aten and the Temple of Amenhotep IV.

See also

References

- Spence, Kate. "Akhenaten and the Amarna Period". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- Doyle, Noreen (September 2007). "Akhenaten's ART". Calliope. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- Hill, Jenny. "Amarna Art". ancientegyptonline.co.uk. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

External links

- 'Gifts for the Gods: Images from Egyptian Temples, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on Amarna art

| Amarna Period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharaohs |  | ||||

| Royal family |

| ||||

| |||||

| Locations | |||||

| Other | |||||