This is an old revision of this page, as edited by AnomieBOT (talk | contribs) at 13:55, 12 January 2016 (Dating maintenance tags: {{Cn}}). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:55, 12 January 2016 by AnomieBOT (talk | contribs) (Dating maintenance tags: {{Cn}})(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)- Not to be confused with Karaites.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Keraites" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| KeraitesKhereid | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th century–13th century | |||||||||||

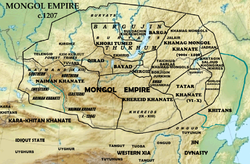

The Mongol Empire c. 1207 (Khereid indicated in the centre south) The Mongol Empire c. 1207 (Khereid indicated in the centre south) | |||||||||||

| Status | khanate | ||||||||||

| Religion | Church of the East | ||||||||||

| Government | Khanate | ||||||||||

| Khan | |||||||||||

| • 11th century | Markus Buyruk Khan | ||||||||||

| • 12th century | Saryk Khan | ||||||||||

| • 12th century | Kurchakus Buyruk Khan | ||||||||||

| • –1203 | Tooril Khan (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

| • Established | 11th century | ||||||||||

| • absorbed into the Mongol Empire. | 13th century | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

The Keraites (also Kerait, Karait; modern Mongolian Хэрэйд, Khereid) was one of the five dominant Mongol tribal confederations (khanates) in the Mongolian plateau during the 12th century. They had converted to the Church of the East (Nestorianism) in the early 11th century and are one of the possible sources of the European Prester John legend.

Their original territory was no doubt expansive, corresponding to much of what is now Mongolia. Vasily Bartold (1913) located them along the upper Onon and Kerulen rivers and along the Tula. They were defeated by Genghis Khan in 1203 and became influential in the rise of the Mongol Empire, and were gradually absorbed into the succeeding Turco-Mongol khanates during the 13th century. Christianity among the Mongols was mostly extinct in the late 14th century due to the Islamization under Timur Lenk.

Name

The name is recorded in Perso-Arabic spelling as كرايت or كريت (kārayit, karayit). In English, the name is variously adopted as Keraites, Karaits, Karait, Kerait, Kereyit.

According to the early 14th-century work Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, Mongol legend traced the clan back to eight brothers with unusually dark faces whose confederation they founded was called Kerait (after a word for "black, swarthy"). Kerait was the name leading brother's clan, while the clans of his brothers are recorded as Jirkin, Konkant, Sakait, Tumaut, Albat.

The Mongolian word kara "black" is cognate with Turkic qarā "black", and the Mongol tribal name became historically conflated with various other Turkic tribal names involving the term.

History

Origins

The Keraites first enter into history as the ruling faction of the Zubu confederacy, a large alliance of tribes that dominated Mongolia during the 11th and 12th centuries and often fought with the Liao Dynasty of northern China, which controlled much of Mongolia at the time.

It is unclear whether the Keraites should be classified as Turkic or Mongol in origin. The names and titles of early Keraite leaders suggest that they were speakers of a Turkic language, but coalitions and incorporation of sub-clans may have led to Turco-Mongol amalgamation from an early time.

They are first noted in Syriac Church records which mention them being absorbed into the Church of the East around AD 1000 by Metropolitan Abdisho of Merv.

Khanate

After the Zubu confederacy broke up, the Keraites retained their dominance on the steppe right up until they were absorbed into Genghis Khan's Mongolian state.

At the height of its power, the Keraites khanate was organized along the same lines as the Naimans and other powerful steppe tribes of the day. A section is dedicated to the Keraites by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani (1247–1318), the official historian of the Genghisid court in Persia, in his Jami' al-tawarikh (c. 1300). The people was divided into a "central" faction and an "outer" faction. The central faction served as the khan's personal army and was composed of warriors from many different tribes with no loyalties to anyone but the Khan. This made the central faction more of a quasi-feudal state than a genuine tribe. The "outer" faction was composed of tribes that pledged obedience to the khan, but lived on their own tribal pastures and functioned semi-autonomously. The "capital" of the Keraite khanate was a place called Orta Balagasun, which was probably located in an old Uyghur or Khitan fortress.

Markus Buyruk Khan, was a Khereid leader who also led the Zubu confederacy. In 1100, he was killed by the Liao Dynasty. Kurchakus Buyruk Khan was a son and successor of Bayruk Markus, among whose wives was Toreqaimish Khatun, daughter of Korchi Buiruk Khan of the Naiman.

Kurchakus's younger brother was Gur Khan. Kurchakus Buyruk Khan had many sons. Notable sons was Toghrul, Yula-Mangus, Tai-Timur, Bukha-Timur. In union with the Khitan they became vassals in the the Kara-Khitai state.

After Kurchakus Buyruk Khan died, Ilma's Tatar servant Eljidai became the de facto regent. This upset Toghrul who had his younger brothers killed and then claimed the throne as Toghrul khan (Mongolian:Тоорил хан/Tooril khan) who was the son of Kurchakus by Ilma Khatun, reigned from the 1160s to 1203. His palace was located at present-day Ulan Bator and he became blood-brother (anda) to Yesugei. Genghis Khan called him khan etseg ('khan father'). Yesugei, having disposed of all Tughrul's sons, was now the only one in line to inherit the title khan.

The Tatars rebelled against the Jin dynasty in 1195. The Jin commander sent an emissary to Timujin. A fight with the Tatars broke out and the Mongol alliance defeated them. In 1196, the Jin Dynasty awarded Toghrul the title of "Wang" (king). After this, Toghrul was recorded under the title "Wang Khan" (Ван хан/Van khan; Chinese: 王汗; pinyin: Wáng Hàn; also Ong Khan). When Timujin attacked Jamukha for the title of Khan, Toghrul, fearing Timujin's growing power, plotted with Jamukha to have Timujin assassinated.

In 1203, Timujin defeated the Keraites, who were distracted by the collapse of their own coalition. Toghrul was killed by Naiman soldiers who failed to recognize him as the former was fleeing from a defeat against Genghis Khan.

Mongol Empire

Genghis Khan married Toghrul's son Tolui to one of Toghrul's nieces, the Nestorian Christian Sorghaghtani Bekhi, the younger daughter of Tooril's brother Jakha Khambu. Tolui and Sorghaghtani Bekhi became the parents of Möngke Khan and Kublai Khan. The remaining Keraites submitted to Timujin's rule, but out of distrust, Timujin dispersed them among the other Mongol tribes.

Rinchin protected Christians when Ghazan began to persecute them but he was executed by Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan when fighting against his custodian, Chupan of the Taichiud in 1319.

Keraites arrived in Europe with the Mongol invasion led by Batu Khan and Mongke Khan. A portion were settled in Carpathian Galicia as a result of a hostage exchange treaty between Batu Khan and the Catholic Rus' Prince Daniel of Carpathian Galicia in 1246.

From the 1380s onward, Nestorian Christianity in Mongolia was destroyed, on the one hand due to the Islamization under Timur and on the other due to the Ming conquest of Karakorum. Mongolian Christians sought refuge under the leadership of Tokhtamysh, and they appear to have lost all contact with their mother church after the schism of 1552. Many were absorbed into other churches, some adopted Islam, while still others became Judaizers.

Nestorian Christianity

Main article: Christianity among the MongolsThe Khereid were converted to Nestorianism, a sect of Christianity, early in the 11th century. Other tribes evangelized entirely or to a great extent during the 10th and 11th centuries were the Naiman and the Ongud.

Rashid al-Din, the official historian of the Mongol court in Persia, in his Jami al-Tawarikh states that the Keraites were Christians. William of Rubruck, who encountered many Nestorians during his stay at Mongke Khan's court and at Karakorum in 1254–1255, notes that Nestorianism in Mongolia was tainted by shamanism and Manicheism and very confused in terms of liturgy, not following the usual norms of Christian churches elsewhere in the world. He attributes this to the lack of teachers of the faith, power struggles among the clergy and a willingness to make doctrinal concessions in order to win the favour of the Khans. Contact with the Catholicos was lost after the Islamization under Timur (reigned 1370–1405), who effectively destroyed the Church of the East. The Nestorian Church in Karakorum was destroyed by the invading Ming dynasty army in 1380.

The legend of Prester John, otherwise set in India or Ethiopia, was also brought in connection with the Nestorian rulers of the Khereid. In some versions of the legend, Prester John was explicitly identified with Toghrul. But Mongolian sources say nothing about his religion.

Conversion account

An account of the conversion of the Khereid is given by the 13th-century Jacobite historian Gregory Bar Hebraeus and also in Mari ibn Suleiman's "Book of the Tower" (Kitab al-Majdal) written in 1145–1150. According to Bar Hebraeus and Mari ibn Suleiman, in 1007 or 1012, a Khereid king lost his way during a snowstorm while hunting in the high mountains of his land. When he had abandoned all hope, a saint (Mar Sergius or Saint Sergius) appeared in a vision and said, "If you will believe in Christ, I will lead you lest you perish." The king promised to "become a lamb in the Christian sheepfold" (join the Church). The saint told him to close his eyes and he found himself back home (Bar Hebraeus' version says the saint led him to the open valley where his home was). When he met Christian merchants, he remembered the vision and asked them about the Christian religion, prayer and the book of canon laws. They taught him "the Lord's Prayer, Lakhu Mara, and Qadisha Alaha." The Lakhu Mara is the Syriac of the hymn Te deum, and the Qadisha Alaha is the Trisagion. At their suggestion, he sent a message to Abdisho, the Metropolitan of Merv, for priests and deacons to baptize him and his tribe. Abdisho sent a letter to Yohannan VI, the Catholicos or Patriarch of the Church of the East in Baghdad (63rd Patriarch after Saint Thomas). Abdisho informed Yohannan VI that the Keraite khan asked him about fasting, whether they could be exempted from the usual Christian way of fasting, since their diet was mainly meat and milk.

Abdisho also related that the Keraite khan had already "set up a pavilion to take the place of an altar, in which was a cross and a Gospel, and named it after Mar Sergius, and he tethered a mare there and he takes her milk and lays it on the Gospel and the cross, and recites over it the prayers which he has learned, and makes the sign of the cross over it, and he and his people after him take a draft from it." Yohannan (John) replied to Abdisho telling him one presbyter (priest) and one deacon was to be sent with altar paraments to baptize the king and his people. Yohannan also approved the exemption of the Keraites from strict church law, stating that while they had to abstain from meat during the annual Lenten fast like other Christians, they could still drink milk during that period, although they should switch from "sour milk" (fermented mare's milk) to "sweet milk" (normal milk) to remember the suffering of Christ during the Lenten fast. The Catholicos also told Abdisho to endeavor to find wheat and wine for them, so they can celebrate the Paschal Eucharist. As a result of the mission that followed, the king and 200,000 of his people were baptized (both Bar Hebraeus and Mari ibn Suleiman give the same number).

Legacy

Various groups have been proposed as derived from the Keraites, e.g. the Karakalpak, Karachay-Balkar, Karaimean, Kara-Tatar, and other Kipchak groups such as Bashkirs, Kazakhs (Middle Juz) and the Kyrgyz Kireis. Koreans of Koran (거란, i.e. Khitan) heritage and a modern Mongolians clan designated as Khereid (Хэрэйд) also claim descent.

Some Karaite Jews in Lithuania have also recently laid claim to this same "Turkic Karaite" identity (whom they relate to the Kara-Khazars) by going through a process of "Dejuzaization" in the 20th century led by Seraja Szapszal in order to survive the anti-Semitic climate.

See also

References

- V.V. Bartold in the article on Genghis Khan in the 1st edition of the Encyclopedia of Islam (1913); see Dunlop (1944:277)

- Dunlop (1944:276)

- Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, Jami' al-tawarikh cited after Template:Ru-icon translation by L.A. Khetagurov (1952) "It is said that in ancient times was the king; He had seven sons, all of them swarthy. For this reason they were called Kerait. After a time, each of the branches, and the progeny of those sons got a special name and nickname. Until very recently, in Kerait was the name of one branch, the sovereign one; the other sons became the servants of his brother, who was their sovereign, while they did not have sovereignty."

- "EAS 107, Владимирцов 324, ОСНЯ 1, 338, АПиПЯЯ 54-55, 73, 103-104, 274. Despite TMN 3, 427, Щербак 1997, 134, there is no need to regard the Mong. word as borrowed from Turkic (although it is not excluded)." Tower of Babel Mongolian etymology database.

- ^ R. Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, New Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, 1970, p191.

- "At that time they had more power and strength than other tribes. The call of Jesus - peace be upon him - reached them and they entered his faith. They belong to the Mongol ethnicity. They reside along the Onon and Kerulen rivers, the land of the Mongols. That land is close to the country of the Khitai. are much at odds with many tribes, especially tribes of the Naiman." Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, Jami' al-tawarikh cited after Template:Ru-icon translation by L.A. Khetagurov (1952)

- ^ Li, Tang (2006). "Sorkaktani Beki: A prominent Nestorian woman at the Mongol Court". Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8050-0534-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - "Galicia: A Historical Survey and Bibliographic Guide", Paul R. Magocsi, University of Toronto Press, 1983. p.252

- Erica C. D. Hunter, “The Conversion of the Khereid to Christianity in A.D. 1007”, Zentralasiatische Studien, 22 (1989–1991), 143–163. Silverberg, Robert (1972). The Realm of Prester John. Doubleday. p. 12.

- Kingsley Bolton; Christopher Hutton (2000). Triad Societies: Western Accounts of the History, Sociology and Linguistics of Chinese Secret Societies. Taylor & Francis. pp. xlix–. ISBN 978-0-415-24397-1.

- Atwood, Christopher P. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. ISBN 0816046719.

- Moffett, A History of Christianity in Asia pp. 400-401.

- "Identity in Transition: The Case of Polish Karaites in the First Half of the 20th Century" Dovile Troskovaite

- Template:Ru-icon Khoyt, S.K., Кереиты в этногенезе народов Евразии: историография проблемы ("Keraites in the ethnogenesis of the peoples of Eurasia: historiography of the problem"), Elista: Kalmyk State University Press (2008).

- Template:Ru-icon КЕРЕИ Мухамеджан Тынышбаев "Материалы по истории казахского народа", Tashkent, 1925.

- Template:Ru-icon КЕРЕИ Шакарим Кудайберды-Улы "Родословная тюрков, киргизов, казахов и ханских династий", перевод Бахыта Каирбекова, Alma-Ata, 1990.

- Unesco. History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volym 4. p. 74.

- Douglas Morton Dunlop, The Karaits of East Asia", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1944, 276–289.

- Togan, İsenbike, "Flexibility and Limitation in Steppe Formations: the Kerait Khanate and Chinggis Khan" in: The Ottoman Empire and its Heritage, Vol. 15, Leiden: Brill (1998).

- Hunter, Erica C. D., "The Conversion of the Kerait to Christianity in A.D. 1007," Zentralasiatische Studien 22 (1989/1991), 142–163.

- Németh, Julius, "Kereit, Kérey, Giray" Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher 36 (1965), 360–365.

- Boyle, John Andrew, "The Summer and Winter Camping Grounds of the Kereit," Central Asiatic Journal 17 (1973), 108-110.

| Mongolic peoples | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||||||

| Proto-Mongols | |||||||||||

| Medieval tribes | |||||||||||

| Ethnic groups |

| ||||||||||

| See also: Donghu and Xianbei · Turco-Mongol Mongolized ethnic groups.Ethnic groups of Mongolian origin or with a large Mongolian ethnic component. | |||||||||||