This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 66.245.23.115 (talk) at 22:55, 16 September 2006 (→External links). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:55, 16 September 2006 by 66.245.23.115 (talk) (→External links)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| It has been suggested that Trooping fairies and Talk:Fairy be merged into this article. (Discuss) |

A fairy (sometimes seen as fairie or faerie; collectively wee folk) is a spirit or supernatural being that is found in the legends, folklore, and mythology of many different cultures. They are generally humanoid in their appearance and have supernatural abilities such as the ability to fly, cast spells and to influence or foresee the future. Although in modern culture they are often depicted as young, sometimes winged, females of small stature, they originally were of a much different image: tall, angelic beings and short, wizened trolls being some of the commonly mentioned fay. The small, gauzy-winged fairies that are commonly depicted today did not appear until the 1800s.

Etymology

The words fae and faerie came to English from Old French which originated in the Latin word "Fata" which referred to the three mythological personifications of destiny, the Greek Moirae (Roman Parcae, "sparing ones", or Fatae) who were supposed to appear three nights after a child's birth to determine the course of its life. They were usually described as cold, remorseless old crones or hags (in contrast to the modern physical depiction). The Latin word gave modern Italian's fata, Catalan and Portuguese fada and Spanish hada, all of which mean fairy. The Old French fée, had the meaning "enchanter." Thus féerie meant a "state of fée" or "enchantment." Fairies are often depicted enchanting humans, casting illusions to alter their emotions and perceptions so as to make themselves at times alluring, frightening, or invisible. Modern English inherited the two terms "fae" and "fairy," along with all the associations attached to them.

A similar word, "fey," has historically meant "doomed to die," mostly in Scotland, which tied in with the original meaning of fate. It has now gained the meaning "touched by otherworldly or magical quality; clairvoyant, supernatural." In modern English, the word seems to be conjoining into "fae" as variant spelling. If "fey" derives from "fata," then the word history of the two words is the same.

Strictly, there should be distinctions between the usage of the two words "fae" and "faerie." "Fae" is a noun that refers to the specific group of otherworldly beings with mystical abilities (either the elves (or equivalent) in mythology or their insect-winged, floral descendants in English folklore), while "faerie" is an adjective meaning "of, like, or associated with fays, their otherworldly home, their activities, and their produced goods and effects." Thus, a leprechaun and a ring of mushrooms are both faerie things (a fairy leprechaun and a fairy ring.), although in modern usage fairy has come to be used as a noun.

Fairies in literature and legend

The question as to the essential nature of fairies has been the topic of myths, stories, and scholarly papers for a very long time.

Practical beliefs

When considered as beings that a person might actually encounter, fairies were noted for their mischief and malice. For instance, "elf-locks" are tangles that are put in the hair of sleepers.

As a consequence, practical considerations of fairies have normally been advice on averting them. Cold iron is the most familiar, but other things are regarded as detrimental to the fairies: wearing clothing inside out, running water, bells (especially church bells), St. John's wort, and four-leaf clovers, among others. While many fairies will confuse travelers on the path, the will o' the wisp can be avoided by not following it. Certain locations, known to be haunts of fairies, are to be avoided; C. S. Lewis reported hearing of a cottage more feared for its reported fairies than its reported ghost. In particular, digging in fairy hills was unwise. Paths that the fairies travel are also wise to avoid. Home-owners have knocked corners from houses because the corner blocked the fairy path, and cottages have been built with the front and back doors in line, so that the owners could, in need, leave them both open and let the fairies troop through all night. Good house-keeping could keep brownies from spiteful actions, and such water hags as Peg Powler and Jenny Greenteeth, prone to drowning people, could be avoided with the body of water they inhabit.

A considerable amount of lore about fairies revolves about changelings and preventing a baby from being thus abducted.

A good number of folk tales about fairies are warnings about the dangers of negligence in this area.

Fairy tales and legends

Some of the most well-known tales in the English and French traditions were collected in the "colored" fairy books of Scottish man of letters Andrew Lang between 1889 and 1910. These stories depict fairies in somewhat contradictory ways — kindly and dangerous, steadfast and fickle, loving and aloof, simple and unknowable — when, indeed, they depict fairies at all, as fairy tales need not involve any fairies at all. J. R. R. Tolkien described these tales as taking place in the land of Faerie. Additionally, any stories that feature faires are not generally categorized as fairy tales.

In many legends, the fairies are prone to kidnapping humans, either as babies, leaving changelings in their place, or as young men and women. This can be for a time or forever, and may be more or less dangerous to the kidnapped. In Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight Child Ballad #4, the elf-knight is a Bluebeard figure, and Isabel must trick and kill him to preserve her life. Tam Lin reveals that the title character, though living among the fairies and having fairy powers, was in fact an "earthly knight" and, though his life was pleasant now, he feared that the fairies would pay him as their teind to hell. Sir Orfeo tells how Sir Orfeo's wife was kidnapped by the King of Faerie and only by trickery and excellent harping ability was he able to win her back. Thomas the Rhymer shows Thomas escaping with less difficulty, but he spends seven years in Faerie. Oisín is harmed not by his stay in Faerie but by his return; when he dismounts, the three centuries that have passed catch up with him, reducing him to an aged man.

A common feature of the fairies is the use of magic to disguise appearance. Fairy gold is notoriously unreliable, appearing as gold when paid, but soon thereafter revealing itself to be leaves, or gingerbread cakes, or a variety of other useless things.

These illusions are also implicit in the tales of fairy ointment. Many tales from the British islands tell of a mortal woman summoned to attend a fairy birth — sometimes attending a mortal, kidnapped woman's childbed. Invariably, the woman is given something for the child's eyes, usually an ointment; though mischance, or sometimes curiosity, she uses it on one or both of her own eyes. At that point, she sees where she is; one midwife realizes that she was not attending a great lady in a fine house but her own runaway maid-servant in a wretched cave. She escapes without making her ability known, but sooner or later betrays that she can see the fairies. She is invariably blinded in the eye where she can, or in both if she used the ointment on both.

Literature

Fairies were taken up as characters in medieval chansons de gestes and lais, as when Huon of Bordeaux is aided by the fairy king Oberon, and Sir Launfal takes a fairy lover, and is nearly lost when he breaks her prohibition not to speak of her (a prohibition not only fitting fairies' secretive nature, but the ethos of courtly love).

William Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream deals extensively with the subject of fairy-folk and their interaction with a group of amateur theatrical players. This work details the spell cast by the mischievous fairy Puck (at the behest of the fairy-king Oberon) on Oberon's wife Titania, who falls in love with the first mortal she casts eyes upon, the unfortunate Bottom, whom Puck has transmogrified into having a donkey's head. Orson Scott Card's Magic Street adds new fairy lore to Shakespeare's story and offers an alternative history of the play.

Shakespeare carefully put in the mouth of his fairies:

- PUCK: My fairy lord, this must be done with haste,

- For night's swift dragons cut the clouds full fast,

- And yonder shines Aurora's harbinger;

- At whose approach, ghosts, wandering here and there,

- Troop home to churchyards: damned spirits all,

- That in crossways and floods have burial,

- Already to their wormy beds are gone;

- For fear lest day should look their shames upon,

- They willfully themselves exile from light

- And must for aye consort with black-brow'd night.

- OBERON: But we are spirits of another sort:

- I with the morning's love have oft made sport,

- And, like a forester, the groves may tread,

- Even till the eastern gate, all fiery-red,

- Opening on Neptune with fair blessed beams,

- Turns into yellow gold his salt green streams.

This was a wise precaution in the era of witch-hunts, when James I of England, writing a treatise on demonology, included many fairies as types of demons. This encouraged, when fairies were used in literature, a light and fanciful touch, to disassociate them with those spirits.

The fairies became progressively more fanciful, until Andrew Lang, explaining that his collections, mentioned above, were all old fairy tales, complained of Victorian fairy tales:

- They always begin with a little boy or girl who goes out and meets the fairies of polyanthuses and gardenias and apple blossoms: 'Flowers and fruits, and other winged things.' These fairies try to be funny, and fail; or they try to preach, and succeed.

In his Fairy Folk Tales of Ireland (1892), W. B. Yeats coined the expression "trooping fairies" to refer to those fairies who liked to travel together in groups, related to the sidhe, Christianised remnants of the Tuatha Dé Danann. This is in contrast to the solitary fairies, such as the banshee, leprechaun, or pooka. Typically Yeats's trooping fairies are compared to the elves of English lore.

In the earlier versions of Tolkien's Middle-earth, the creatures later known as Elves were called Fairies.

Howevers, this use gave way, which has been a major influence on the use of fairies in fantasy literature. On one hand, Tolkien removed much of the Victorian connotation of elves; delicate, dainty little creatures (often with butterfly wings) are far more likely to be fairies than elves. On the other, Tolkien also humanized elves; terrifying, other-worldly creatures with minds and powers that mortals can not fathom — Margaret Ball's No Earthly Sunne — are also more likely to be fairies than elves, although such works as Terry Pratchett's Lords and Ladies show the influence of old folklore when dealing with elves.

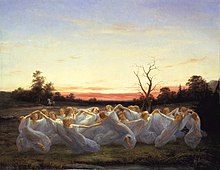

Fairies in art

See also Fairy painting

Fairies have been numerously depicted in books of fairy tales and sometimes as standalone works of art and sculpture. Some artists known for their depictions of fairies include:

- Alan Lee

- Arthur Rackham

- Brian Froud

- Cicely Mary Barker

- Ida Rentoul Outhwaite

- Myrea Pettit

- Richard de Chazal in his Four Seasons series of photographs

The Victorian painter Richard Dadd created paintings of fairy-folk with a sinister and malign tone. Other Victorian artists who depicted fairies include John Atkinson Grimshaw, Joseph Noel Paton, John Anster Fitzgerald and Daniel Maclise. Interest in fairy themed art enjoyed a brief renaissance following the publication of the Cottingley fairies photographs in 1917 and a number of artists turned to painting fairy themes.

Cottingley Fairies

The Cottingley Fairies refers to a series of five photographs taken by Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright, two young cousins living in Cottingley, Bradford, England.

The first two photos were taken in 1917. They were publicized in 1920 when The Strand published a piece by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle showing the first two photographs and describing them. Griffiths and Wright were then given 24 photographic plates and took three more photos in August 1920. They blamed constant rainfall, but rainfall was at the lowest point in the year during August. This is now seen as proof that they had to discard several failed attempts. The photos showed the fairies as small humans with period style haircuts, dressed in filmy gowns, and with large wings on their backs. One picture is of a gnome, about 12 inches tall, dressed in a somewhat Elizabethan manner, and also with wings.

At the time, the photos were viewed by some as evidence of fairies, most notably Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle wrote a book called The Coming of the Fairies, about the Cottingley Fairies and his belief in them.

In the pictures and prints available today, the fairies look flat, with lighting that does not match the rest of the photograph, as if they were paper cut-outs. It has been claimed that this is because the originals were of poor quality and needed retouching and that this is the reason the originals were first seen as convincing. Harold Snelling, a contemporary expert in fake photography, said "these dancing figures are not made of paper nor any fabric; they are not painted on a photographic background—but what gets me most is that all these figures have moved during the exposure." However in the long exposure (see waterfall in above photo), wind could have moved the fairies' wings or bodies if they were made of paper or fabric. Doyle also dismissed the idea that the photographs could have been faked. It is now considered that he thought the girls too young and too inexperienced to have been able to create such a hoax.

In 1978, it was found the fairies were from the 1915 book Princess Mary's Gift Book by Arthur Shepperson.

The cousins remained evasive about the authenticity of the pictures for most of their lives, at times claiming they were forgeries, and at other times leaving it to the individual to decide. In 1981, in an interview by Joe Cooper for the magazine The Unexplained, the cousins confessed that the photos were fake and they held up cut-outs with drawing pins. Frances Griffiths, however, continued to maintain until her death that they did see fairies and that the fifth photograph, which showed fairies in a sunbath, was genuine.

Two 1997 films, Fairy Tale: A True Story, starring Peter O'Toole and Harvey Keitel, and Photographing Fairies with Ben Kingsley, were based on this event.

Fairies in modern culture and film

Fairies are often depicted in books, stories, and movies. A number of these fairies are from adaptations of traditional tales. Perhaps the most well-known is Tinkerbell, from the Peter Pan stories by J.M. Barrie and the Disney adaptation. She is also often referred to as a pixie, and leaves a trail of fairy dust (or pixie dust) behind wherever she goes. In Carlo Collodi's tale Pinocchio a wooden boy receives the gift of real life from the Blue Fairy. Neil Gaiman's book Stardust explores the journey of a young man into Faerie, and the movie is currently in the making. Other books center around the secret lives of fairies, such as the Artemis Fowl books. Fairies even appear in videogames, such as The Legend of Zelda. Fae stories focusing on modern settings include Holly Black's Tithe, and Cajun Fairies-In the Land of Sha Bebe, by Mary Lynn Plaisance, which add to the diversity of modern faerie fiction.

See also

- Aziza

- Adhene

- Alux

- Bugul Noz

- Curupira

- Duende

- Encantado

- Enchanted Lady Moor

- Fairy riding

- Jogah

- Leprechaun

- List of fairy and sprite characters

- Mogwai

- Paristan

- Peri

- Photographing fairies

- Preserver (Elfquest)

- Seelie

- Sidhe

- Sprite (creature)

- Slavic fairies

- Titania's Palace

- Tooth fairy

- Trooping fairies

- Wichtlein

Bibliography

- Gordon Ashliman, Fairy Lore: A Handbook (Greenwood, 2006)

- Brian Froud and Alan Lee, Faeries, (Peacock Press/Bantam, New York, 1978)

- L. Henderson and E.J. Cowan, Scottish Fairy Belief (Edinburgh, 2001)

- Peter Narvaez, The Good People, New Fairylore Essays (Garland, New York, 1991)

- C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature (1964)

- Patricia Lysaght, The Banshee: the Irish Supernatural Death Messenger (Glendale Press, Dublin, 1986)

- Eva Pocs, Fairies and Witches at the boundary of south-eastern and central Europe FFC no 243 (Helsinki, 1989)

- Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A History of Fairies and Fairy Stories (Allen Lane, 2000)

- Ronan Coghlan, Handbook of Fairies (Capall Bann, 2002)

External links

- Academic discussion on BBC Radio 4's In Our Time, May 11, 2006 (streaming and podcast)

- Fairies in Art

- Creatures by Type : Fairies

- Fairy Tattoos & Pictures

- The Story of Anne Jefferies and the Fairies

- Away with the Fairies ASSAP article

- Kalash Fae of Pakistan

- Ancient and Modern Fairies in the myriad of global culture

- Fairies Lots of fairy images which are in the public domain