This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Jonny-mt (talk | contribs) at 05:04, 28 September 2006 (Inserted "Practical application" section, rewrote most of article ~~~~). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:04, 28 September 2006 by Jonny-mt (talk | contribs) (Inserted "Practical application" section, rewrote most of article ~~~~)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Transfer pricing refers to the pricing of goods and services within a multi-divisional organization, particularly in regard to cross-border transactions. For example, goods from the production division may be sold to the marketing division, or goods from a parent company may be sold to a foreign subsidiary, with the choice of the transfer price affecting the division of the total profit among the parts of the company. This has led to the rise of transfer pricing regulations as governments seek to stem the flow of taxation revenue overseas, making the issue one of great importance for multinational corporations.

Economic theory

The discussion below explains the economic theory, but in practice a great many factors influence the transfer prices that are used by multinationals, including performance measurement, capabilities of accounting systems, import quotas, customs duties, VAT, taxes on profits, and (in many cases) simple lack of attention to the pricing.

From marginal price determination theory, we know that generally the optimum level of output is that where marginal costs equals marginal revenue. That is to say, a firm should expand its output as long as the marginal revenue from additional sales is greater than their marginal costs. In the diagram that follows, this intersection is represented by point A, which will yield a price of P*, given the demand at point B.

When a firm is selling some of its product to itself, and only to itself (ie.: there is no external market for that particular transfer good), then the picture gets more complicated, but the outcome remains the same. The demand curve remains the same. The optimum price and quantity remain the same. But marginal cost of production can be separated from the firms total marginal costs. Likewise, the marginal revenue associated with the production division can be separated from the marginal revenue for the total firm. This is referred to as the Net Marginal Revenue in production (NMR), and is calculated as the marginal revenue from the firm minus the marginal costs of distribution.

Transfer Pricing with No External Market

It can be shown algebraically that the intersection of the firms marginal cost curve and marginal revenue curve (point A) must occur at the same quantity as the intersection of the production divisions marginal cost curve with the net marginal revenue from production (point C).

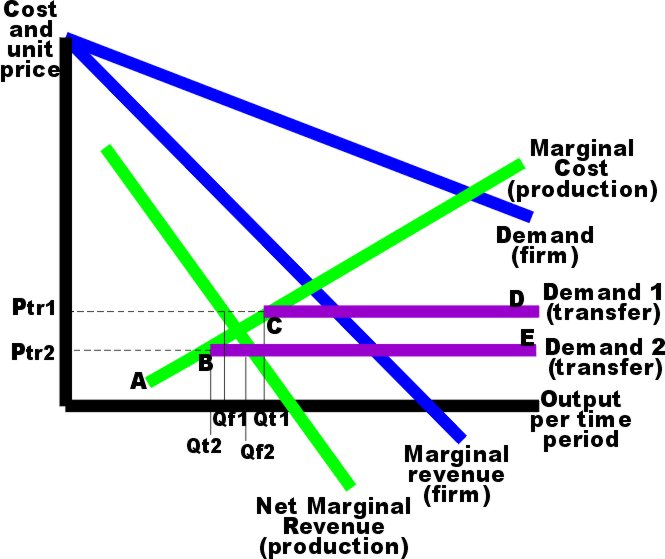

If the production division is able to sell the transfer good in a competitive market (as well as internally), then again both must operate where their marginal costs equal their marginal revenue, for profit maximization. Because the external market is competitive, the firm is a price taker and must accept the transfer price determined by market forces (their marginal revenue from transfer and demand for transfer products becomes the transfer price). If the market price is relatively high (as in Ptr1 in the next diagram), then the firm will experience an internal surplus (excess internal supply) equal to the amount Qt1 minus Qf1. The actual marginal cost curve is defined by points A,C,D.

Transfer Pricing with a Competitive External Market

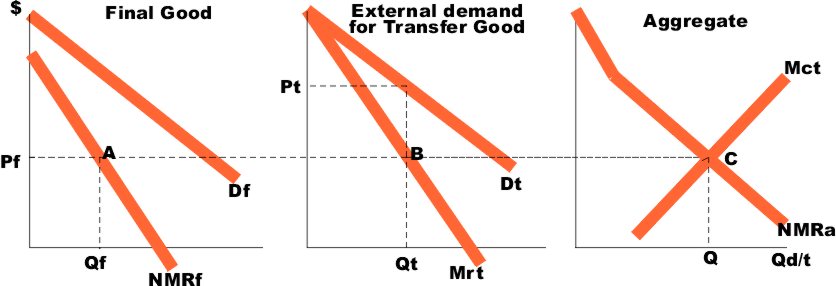

If the firm is able to sell its transfer goods in an imperfect market, then it need not be a price taker. There are two markets each with its own price (Pf and Pt in the next diagram). The aggregate market is constructed from the first two. That is, point C is a horizontal summation of points A and B (and likewise for all other points on the Net Marginal Revenue curve (NMRa)). The total optimum quantity (Q) is the sum of Qf plus Qt.

Transfer Pricing with an Imperfect External Market

Practical application

Role of administrative regulations and guidelines

Although there is sound economic theory behind the selection of a transfer pricing method, the fact remains that it can be advantageous to arbitrarily select prices such that, in terms of bookkeeping, most of the profit is made in a country with low taxes, thus shifting the profits to reduce overall taxes paid by a multinational group. However, most countries enforce tax laws based on the arm's length principle as defined in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations, limiting how transfer prices can be set and ensuring that that country gets to tax its "fair" share. In the United States, the pricing of transactions between related parties that are reported for tax purposes are governed by Section 482 of the Internal Revenue Code and the regulations thereunder.

From the corporation's position, running afoul of such regulations can prove to be a costly mistake, as illustrated by GlaxoSmithKline's announcement on September 11, 2006 that they had settled a long-running transfer pricing dispute with the US tax authorities, agreeing to pay over $5 billion in taxes related to an assessed income adjustment due to improper transfer pricing. However, proper use of the regulations also provides a method of protecting against double taxation, provided that the transactions are carried out between divisions in countries bound by bilateral tax treaties. In the GlaxoSmithKline case, however, the company has indicated that they will not pursue competent authority negotiations for the relief of U.S.-U.K. double taxation.

Calculation of the arm's length price

Although there are discrepancies in the specifics of each country's laws concerning the calculation of the arm's length price, the fact that they are primarily based in the OECD Guidelines means that, although such a strategy carries a greater taxation risk than solutions tailored to each country, global transfer pricing policies can be effectively used to determine an appropriate range representing the arm's length price for transactions carried out across a global enterprise.

It is important to note, however, that different countries may accept different methods of calculating the transfer price (i.e. Japan requires that the three "traditional" methods be systematically discounted before allowing the use of alternative methods, while the United States accepts the most appropriate method regardless), so care must be taken in such circumstances.

The following definitions are thus based on the OECD Guidelines.

Traditional methods

Comparable Uncontrolled Price method

The Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) method compares the price at which a controlled transaction is conducted to the price at which a comparable uncontrolled transaction is conducted. This makes it the easiest to conceptually grasp, as the arm's length price is, quite simply, determined by the sale price between two unrelated corporations. However, the fact that virtually any minor change in the circumstances of trade (billing period, amount of trade, branding, etc.) may have a significant affect on the price makes it exceedingly difficult to find a transaction--much less transactions--that are sufficiently comparable.

Should they exist, such comparable transactions fall into two categories: external comparables and internal comparables. The former is a comparable uncontrolled transaction in the purest sense of the term--if Company A, in France, sells widgets to its subsidiary A(sub) in Turkey, then an external comparable transaction would be the sale of widgets from French Company B to Turkish Company C (an unrelated enterprise) on identical terms as the trade between A and A(sub). An internal comparable transaction, then, would be either the trade of widgets between Company A and Company C, or the trade of widgets between Company B and Company A(sub), with the term "internal" referring to the fact that one of the parties involved in the tested transaction is also involved in the comparable uncontrolled transaction.

Cost Plus method

The Cost Plus (CP) method, generally used for the trade of finished goods, is determined by adding an appropriate markup to the costs incurred by the selling party in manufacturing/purchasing the goods or services provided, with the appropriate markup being based on the profits of other companies comparable to the tested party. For example, the arm's length price for a transaction involving the sale of finished clothing to a related distributor would be determined by adding an appropriate markup to the cost of materials, labor, manufacturing, and so on.

Resale Price method

The Resale Price (RP), while similar to the CP method, is found by working backwards from transactions taking place at the next stage in the supply chain, and is determined by subtracting an appropriate gross markup from the sale price to an unrelated third party, with the appropriate gross margin being determined by examining the conditions under which it the goods or services are sold and comparing said transaction to other, third-party transactions. In our clothing example, then, the arm's length price would be determined by subtracting an appropriate gross margin from the price at which the distributor sold the products received from the manufacturer to third-party retailers--department stores, boutiques, etcetera.

It is important to note here that, in our example, both the CP and RP methods are being used to examine the same transaction--the one between the manufacturer and the distributor--meaning that the selection of one for use is ultimately dependent on the availability of data and comparable transactions. This flexibility is not available in other transactions, particularly those involving intangible goods (i.e. it is exceedingly difficult to determine the costs involved in developing technological know-how, and so the arm's length price for the payment of royalties from one company to another is best determined by working backwards from the profits gained based on the usage of the know-how--in other words, the RP method).

Non-traditional methods

There are any number of non-traditional methods available for determining the arm's length price, with the most common being the Profit Split (PS) method and the Transactional Net Margin method (TNMM).

The PS method (and its derivatives, including the Comparative and Residual Profit Split methods) is applied when the businesses involved in the examined transaction are too integrated to allow for separate evaluation, and so the ultimate profit derived from the endeavor is split based on the level of contribution--itself often determined by some measurable factor such as employee compensation, payment of administration expenses, etc.--of each of the participants in the project. To present a highly simplified example, if Company A above sent three researchers to Company A(sub) to aid in the development of widgets tailored for the Turkish market while Company A(sub) allocated seven identically-compensated researchers to aid in the development, we would expect that Company A(sub) would pay Company A 30% of the ultimate profits as a royalty fee for the technical knowledge provided by Company A's researchers.

TNMM, meanwhile, is a method that requires a thorough examination of the company in question in order to determine the net profit margin relative to an appropriate base of costs to be realized through the examined transaction. Essentially, TNMM is a unified version of the RP and CP methods whereby comparable companies are used to ensure an appropriate margin is applied. Although not one of the traditional three methods, TNMM is gaining recognition as a relatively accurate, easy method of calculating the arm's length price.

APA

An Advance Pricing Agreement/Arrangement (the specific terminology varies by country), or APA, is an agreement between the taxpayer and the competent taxation authorities that a future transaction will be conducted at the agreed-upon price, which is recognized as the arm's length price for the period designated. Although retroactive APAs can be used to reduce tax exposure in past years, APAs are primarily used to avoid the risk of future income assessment adjustments which, as in the case of GlaxoSmithKlein, could lead to hefty payments in the future.

There are two types of APAs: unilateral and bilateral/multilateral APAs. A unilateral APA is, as its name suggests, an agreement between a corporation and the authority of the country where it is subject to taxation. Although simpler to implement than a bilateral/multilateral APA, a unilateral APA will not be recognized by a foreign tax authority, meaning that a U.S. company securing a unilateral APA for trade with its British subsidiary would still run the risk of being assessed should the foreign tax authorities not agree with the method of calculating the arm's length price, resulting in double taxation.

Bilateral/multilateral APAs, however, do provide such coverage, although their implementation requires a more lengthy application process, including consultation between and the agreement of all competent authorities involved.

Mutual agreement procedures

A mutual agreement procedure is an instrument used for relieving international tax grievances, including double taxation. Although the specifics vary based on the laws of each country, they are only carried out between authorities of countries or principalities with existing tax treaties--for example, it is impossible to relieve double taxation by holding mutual agreement procedures between the authorities of China and Taiwan.

Is it also important to note that, although most conventions require that each party to put forth all reasonable effort to resolve such disputes, they are generally not required to come to any sort of agreement. This means that although mutual agreement procedures can be an effective tool for the relief of taxation grievances, they are not failsafes.