This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Everything Is Numbers (talk | contribs) at 22:37, 21 June 2017 (wages and salaries are only two types of remuneration). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:37, 21 June 2017 by Everything Is Numbers (talk | contribs) (wages and salaries are only two types of remuneration)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)The gender pay gap is the average difference between a man's and a woman's remuneration.

There are two distinct numbers regarding the pay gap: unadjusted versus adjusted pay gap which takes into account differences in hours worked, occupations chosen, education and job experience. For example, someone who takes time off (e.g. maternity leave) will likely not earn as much as someone who does not take time off from work. Factors like this contribute to lower yearly earnings for women, but when all external factors have been adjusted for, there still exists a gender pay gap in many situations (between 4.8% and 7.1% according to one study). Unadjusted pay gaps are much higher. In the United States, for example the unadjusted average female's annual salary has commonly been cited as being 78% of the average male salary.

The World Economic Forum provides recent data from 2015 that evaluates the gender pay gap in 145 countries. Their evaluations take into account economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment scores.

Over time

A wide-ranging meta-analysis by Doris Weichselbaumer and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer (2005) of more than 260 published adjusted pay gap studies for over 60 countries has found that, from the 1960s to the 1990s, raw wage differentials worldwide have fallen substantially from around 65 to 30%. The bulk of this decline, however, was due to better labor market endowments of women. The 260 published estimates show that the unexplained component of the gap has not declined over time. Using their own specifications, Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer found that the yearly overall decline of the gender pay gap would amount to a slow 0.17 log points, implying a slow level of convergence between the wages of men and women.

Another meta-analysis of 41 empirical studies on the wage gap performed in 1998 found a similar time trend in estimated pay gaps, a decrease of roughly 1% per year.

According to economist Alan Manning of the London School of Economics, the process of closing the gender pay gap has slowed substantially and women could earn less than men for the next 150 years because of discrimination and ineffective government policies. A 2011 study by the British CMI revealed that if pay growth continues for female executives at current rates, the gap between the earnings of female and male executives would not be closed until 2109. Women Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) are paid 16% lower on average as compared to their male counterparts.

By country

| The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (November 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Australia

Main article: Gender pay gap in AustraliaIn Australia, the gender pay gap is calculated on the average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time employees published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The gender pay gap excludes part-time, casual earnings and overtime payments.

Australia has a persistent gender pay gap. Between 1990 and 2009, the gender pay gap remained within a narrow range of between 15 and 17%. In August 2010, the Australian gender pay gap was 16.9%.

Ian Watson of Macquarie University examined the gender pay gap among full-time managers in Australia over the period 2001–2008, and found that between 65 and 90% of this earnings differential could not be explained by a large range of demographic and labor market variables. In fact, a "major part of the earnings gap is simply due to women managers being female". Watson also notes that despite the "characteristics of male and female managers being remarkably similar, their earnings are very different, suggesting that discrimination plays an important role in this outcome". A 2009 report to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs also found that "simply being a woman is the major contributing factor to the gap in Australia, accounting for 60 per cent of the difference between women's and men's earnings, a finding which reflects other Australian research in this area". The second most important factor in explaining the pay gap was industrial segregation. A report by the World Bank also found that women in Australia who worked part-time jobs and were married came from households which had a gendered distribution of labor, possessed high job satisfaction, and hence were not motivated to increase their working hours.

Canada

A study of wages among Canadian supply chain managers found that men make an average of $14,296 a year more than women. The research suggests that as supply chain managers move up the corporate ladder, they are less likely to be female.

Each province and territory in Canada has a quasi-constitutional human rights code which prohibits discrimination based on sex. Several also have laws specifically prohibiting public sector and private sector employers from paying men and women differing amounts for substantially similar work. Verbatim, the Alberta Human Rights Act states in regards to equal pay, "Where employees of both sexes perform the same or substantially similar work for an employer in an establishment the employer shall pay the employees at the same rate of pay."

China

Using the gaps between men and women in economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment, The Global Gender Gap Report 2015 ranks China's gender gap at 91 out of 145 countries (the lower the ranking, the narrower the gender gap), which is four rankings below 2014's global index. China's 2015 gender gap score was 0.681 (1.00 being equality). As an upper middle income country, as classified by the World Bank, China is the "third-least improved country in the world" on the gender gap. The health and survival subindex is the lowest within the countries listed; this subindex takes into account the gender differences of life expectancy and sex ratio at birth (the ratio of male to female children to depict the preferences of sons in accordance with China's One Child Policy). In particular, Jayoung Yoon claims the women's employment rate is decreasing. However, several of the contributing factors might be expected to increase women's participation. Yoon's contributing factors include: the traditional gender roles; the lack of childcare services provided by the state; the obstacle of childrearing; and the highly educated, unmarried women termed "leftover women" by the state. The term "leftover women" produces anxieties for women to rush marriage, delaying employment. In alignment with the traditional gender roles, the "Women Return to the Home" movement by the government encouraged women to leave their jobs to alleviate the men's unemployment rate.

Dominican Republic

Dominican women, who are 52.2% of the labor force, earns an average of 20,479 Dominican pesos, 2.6% more than Dominican men's average income of 19,961 pesos. The Global Gender Gap ranking, found by compiling economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment scores, in 2009 was 67th out of 134 countries representing 90% of the globe, and its ranking has dropped to 86th out of 145 countries in 2015. More women are in ministerial offices, improving the political empowerment score, but women aren't receiving equal pay for similar jobs, preserving the low economic participation and opportunity scores.

European Union

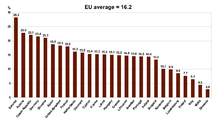

At EU level, the gender pay gap is defined as the relative difference in the average gross hourly earnings of women and men within the economy as a whole. Eurostat found a persisting gender pay gap of 17.5% on average in the 27 EU Member States in 2008. There were considerable differences between the Member States, with the pay gap ranging from less than 10% in Italy, Slovenia, Malta, Romania, Belgium, Portugal, and Poland to more than 20% in Slovakia, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Germany, United Kingdom, and Greece and more than 25% in Estonia and Austria. However, taking into account the hours worked in Finland, men there only earned 0.4% more in net income than women.

A recent survey of international employment law firms showed that gender pay gap reporting is not a common policy internationally. Despite such laws on a national level being few and far between, there are calls for regulation on an EU level. A recent (as of December 2015) resolution of the European Parliament urged the Commission to table legislation closing the pay gap. A proposal that is substantively the same as the UK plan was passed by 344 votes to 156 in the European Parliament.

The European Commission has stated that the undervaluation of female work is one of the main contributors to the persisting gender pay gap.

Germany

Women earned 22–23% less than men, according to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany. The revised gender pay gap was 6–8% in the years 2006–2013. The Cologne Institute for Economic Research adjusted the wage gap to less than 2%. They reduced the gender pay gap from 25% to 11% by taking in account the work hours, education and the period of employment. The difference in revenue was reduced furthermore if women hadn't paused their job for more than 18 months due to motherhood.

The most significant factors associated with the remaining gender pay gap are part-time work, education and occupational segregation (less women in leading positions and in fields like STEM).

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, recent numbers from the CBS (Centraal Bureau voor statistieken; English: Central Bureau of Statistics) claim that the pay gap is getting smaller. Adjusted for occupation level, education level, experience level and 17 other variables the difference in earnings in businesses has fallen from 9% (2008) to 7% (2014) and in government from 7% (2008) to 5% (2014). Without adjustments the gap is for businesses 20% (2014) and government 10% (2014). Young women actually earn more than men up until the age of 30, this is mostly due to a higher level of education. Women in the Netherlands, up until the age of 30, have a higher educational level on average than men; after this age men have on average a higher educational degree. The chance can also be caused by women getting pregnant and start taking part-time jobs so they can care for the children.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the aggregate gender pay gap has been on the decline, and even reversed for certain age groups. According to data from the Office for National Statistics, women aged 22–29 earned ₤1,111 more per year than men of the same age (between 2006 and 2013). As of 2012, the gap officially dropped below 10% for full-time workers. The aggregate gender pay gap can also be viewed as a generational sliding scale. Females between the ages of 55–65 have the largest disparity (18%), while females between the ages of 25–35 have the smallest disparity (6%).

In the UK, the most significant factors associated with the remaining gender pay gap are part-time work, education, the size of the firm a person is employed in, and occupational segregation (women are under-represented in managerial and high-paying professional occupations). When comparing full-time roles, men in the UK tend to work longer hours than women in full-time employment. Depending on the age bracket and percentile of hours worked men in full-time employment work between 1.35% and 17.94% more hours than women in full-time employment. When comparing part-time roles women out-earn men by 6.5% in 2015 (up from 5.5% in 2014).

In October 2014, the Equality Act 2010 was augmented with regulations which require Employment Tribunals to order an employer (except an existing micro-business or a new business) to carry out an equal pay audit where the employer is found to have breached equal pay law.

A 2015 study compiled by the Press Association based on data from the Office for National Statistics revealed that women in their 20s were out-earning men in their 20s by an average of £1,111, suggesting a reversal of trends. However, the same study showed that men in their 30s out-earned women in their 30s by an average of £8775. The study did not attempt to explain the causes of the gender gap.

In April 2018 employers with over 250 employees will be required to publish data relating to pay inequalities. Data published is to include the pay and bonus figures between men and women, and will include data from April 2017.

India

Main article: Gender pay gap in India| This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

Japan

Jayoung Yoon analyzes Japan's culture of the traditional male breadwinner model, where the husband works outside of the house while the wife is the caretaker. Despite these traditional gender roles for women, Japan's government aims to enhance the economy by improving the labor policies for mothers with Abenomix (2013), an economy revitalization strategy. Yoon believes Abenomix represents a desire to remedy the effects of an aging population rather than a desire to promote gender equality. Evidence for the conclusion is the finding that women are entering the workforce in contingent positions for a secondary income and a company need of part-time workers based on mechanizing, outsourcing and subcontracting. Therefore, Yoon states that women's participation rates do not seem to be influenced by government policies but by companies' necessities. The Global Gender Gap Report 2015 established that Japan's economic participation and opportunity ranking (106th), 145th being the broadest gender gap, dropped from 2014 "due to lower wage equality for similar work and fewer female legislators, senior officials and managers".

Jordan

From a total of 145 states, the World Economic Forum calculates Jordan's gender gap ranking for 2015 as 140th through economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment evaluations. Jordan is the "world's second-least improved country" for the overall gender gap. The ranking dropped from 93rd in 2006. In contradiction to Jordan's provisions within its constitution and being signatory to multiple conventions for improving the gender pay gap, there is no legislation aimed at gender equality in the workforce. According to The Global Gender Gap Report 2015, Jordan had a score of 0.61, 1.00 being equality, on pay equality for like jobs.

Korea

As stated by Jayoung Yoon, South Korea's female employment rate has increased since the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis as a result of women 25 to 34 years old leaving the workforce later to become pregnant and women 45 to 49 years old returning to the workforce. Mothers are more likely to continue working after child rearing on account of the availability of affordable childcare services provided for mothers previously in the workforce or the difficulty to be rehired after taking time off to raise their children. The World Economic Forum found that, in 2015, South Korea had a score of 0.55, 1.00 being equality, for pay equality for like jobs. From a total of 145 countries, South Korea had a gender gap ranking of 115th (the lower the ranking, the narrower the gender gap). On the other hand, political empowerment dropped to half of the percentage of women in the government in 2014.

North Korea, on the other hand, is one of few countries where women earn more than men. The disparity is due to women's greater participation in the shadow economy of North Korea.

New Zealand

Main article: Gender pay gap in New Zealand| This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

Russia

Main article: Gender pay gap in Russia| This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

Singapore

According to Jayoung Yoon, Singapore's aging population and low fertility rates are resulting in more women joining the labor force in response to the government's desire to improve the economy. The government provides tax relief to mothers in the workforce to encourage them to continue working. Yoon states that "as female employment increases, the gender gap in employment rates…narrows down" in Singapore. As a matter of fact, The Global Gender Gap Report 2015 ranks Singapore's gender gap at 54th out of 145 states globally based on the economic participation and opportunity, the educational attainment, the health and survival, and the political empowerment subindexes (a lower rank means a smaller gender gap). The gender gap narrowed from 2014's ranking of 59. In the Asia and Pacific region, Singapore has evolved the most in the economic participation and opportunity subindex, yet it is lower than the region's means in educational attainment and political empowerment.

United States

| This section needs additional citations to secondary or tertiary sources. Help add sources such as review articles, monographs, or textbooks. Please also establish the relevance for any primary research articles cited. Unsourced or poorly sourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Looking at the gender pay gap over time, the United States Congress Joint Economic Committee showed that, as explained inequities decrease, the unexplained pay gap remains unchanged. Similarly, according to economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn and their research into the gender pay gap in the United States, a steady convergence between the wages of women and men is not automatic. They argue that after a considerable rise in women's wages during the 1980s, the gain decreased in the 1990s, which was due mainly to a much faster decline in the "unexplained" part of the gap during the 1980s than in the 1990s. They also contend that the slowing of this decline may have been caused by multiple factors, including "changes in labor force selectivity, changes in gender differences in unmeasured characteristics and in labor market discrimination, and changes in the favorableness of demand shifts". A mixed picture of increase and decline characterizes the 2000s. Thus Blau and Kahn assume:

With the evidence suggesting that convergence has slowed in recent years, the possibility arises that the narrowing of the gender pay gap will not continue into the future. Moreover, there is evidence that although discrimination against women in the labor market has declined, some discrimination does still continue to exist.

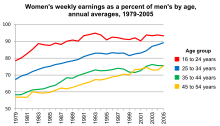

In the United States, the gender pay gap is measured as the ratio of female to male median yearly earnings among full-time, year-round (FTYR) workers. The female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77 in 2012, meaning that, in 2012, female FTYR workers earned 77% as much as male FTYR workers. Women's median yearly earnings relative to men's rose rapidly from 1980 to 1990 (from 60.2% to 71.6%), and less rapidly from 1990 to 2000 (from 71.6% to 73.7%) and from 2000 to 2009 (from 73.7% to 77.0%). More recent statistics show in 2014 that women's median pay has increased to 79 cents, according to the Institute for Women's Policy Research.

The raw wage gap data shows that a woman would earn roughly 73.7% to 77% of what a man would earn over their lifetime. More precisely, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates the median earnings of female workers working full-time to be roughly 77% of the median earnings of their male counterparts. However, when controllable variables are accounted for, such as job position, total hours worked, number of children, and the frequency at which unpaid leave is taken, in addition to other factors, a United States Department of Labor study, conducted by the CONSAD Research Group, found in 2008 that the gap can be brought down from 23% to between 4.8% and 7.1%. Noting that the raw wage gap is the result of a number of factors, the report said that the raw gap should not be used to justify corrective action, adding that "Indeed, there may be nothing to correct. The differences in raw wages may be almost entirely the result of the individual choices being made by both male and female workers."

The gender pay gap has been attributed to differences in personal and workplace characteristics between women and men (education, hours worked, occupation, etc.) as well as direct and indirect discrimination in the labor market (gender stereotypes, customer and employer bias etc.).

The estimates for the discriminatory component of the gender pay gap include 5% and 7% for federal jobs, and a study showed that these grow as men and women's careers progress. One economist testified to Congress that hundreds of studies have consistently found unexplained pay differences which potentially include discrimination. Another criticized these studies as insufficiently controlled, and said that men and women would have equal pay if they made the same choices and had the same experience, education, etc.

Other studies have found direct evidence of discrimination in recruitment. A 2007 study showed a substantial bias against women with children. Another study showed more jobs for women when orchestras moved to blind auditions. One study found that female applicants were favored; however, its results have been met with skepticism from other researchers, since it contradicts most other studies on the issue. Joan C. Williams, a distinguished professor at the University of California's Hastings College of Law, raised issues with its methodology, pointing out that the fictional female candidates it used were unusually well-qualified. Studies using more moderately-qualified graduate students have found that male students are much more likely to be hired, offered better salaries, and offered mentorship.

In 2013, a study performed by Payscale showed that in individual contributor levels, the pay gap is as low as 2%.

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 made changes to the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 to promote a law that prohibit or make it illegal to have different wages between men and women and to "retaliate" or to prevent attack on a person about discrimination.

Impact

Pensions

The European Commission argues that the gender pay gap has far-reaching effects, especially in regard to pensions. Since women's earnings over a lifetime are on average 17.5% (as of 2008) lower than men's, these lower earnings result in lower pensions. As a result, elderly women are more likely to face poverty: 22% of women aged 65 and over are at risk of poverty compared to 16% of men.

Economy

A 2009 report for the Australian Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs argued that in addition to fairness and equity there are also strong economic imperatives for addressing the gender wage gap. The researchers estimated that a decrease in the gender wage gap from 17% to 16% would increase GDP per capita by approximately $260, mostly from an increase in the hours females would work. Ignoring opposing factors as hours females work increase, eliminating the whole gender wage gap from 17% could be worth around $93 billion or 8.5% of GDP. The researchers estimated the causes of the wage gap as follows, lack of work experience was 7%, lack of formal training was 5%, occupational segregation was 25%, working at smaller firms was 3%, and being female represented the remaining 60%.

An October 2012 study by the American Association of University Women found that over the course of 47 years, an American woman with a college degree will make about $1.2 million less than a man with the same education. Therefore, closing the pay gap by raising women's wages would have a stimulus effect that would grow the United States economy by at least 3% to 4%. By increasing women's workplace participation from its present rate of 76% to 84%, as it is in Sweden, the US could add 5.1 million women to the workforce, again, 3% to 4% of the size of the United States economy.

Economic theories

Neoclassical models

In certain neoclassical models, discrimination by employers can be inefficient; excluding or limiting employment of a specific group will raise the wages of groups not facing discrimination. Other firms could then gain a competitive advantage by hiring more workers from the group facing discrimination. As a result, in the long run discrimination would not occur. However, this view depends heavily on strong assumptions about the labor market and the production functions of the firms attempting to discriminate. Firms which discriminate on the basis of real or perceived customer or employee preferences would also not necessarily see discrimination disappear in the long run even under stylized models.

Monopsony explanation

In monopsony theory, wage discrimination can be explained by variations in labor mobility constraints between workers. Ransom and Oaxaca (2005) show that women appear to be less pay sensitive than men, and therefore employers take advantage of this and discriminate in their pay for women workers.

Effect of job choices

In Canada, it is shown that women are more likely to seek employment opportunities which greatly contrast the ones of men. About 20 percent of women, between the ages of 25 and 54, will make just under $12 an hour in Canada. The demographic of women who take jobs paying less than $12 an hour is also a proportion that is twice as large as the proportion of men taking on the same type of low-wage work. There still remains the question of why such a trend seems to resonate throughout the developed world. One identified societal factor that has been identified is the influx of women of color and immigrants into the work force. These groups both tend to be subject to lower paying jobs from a statistical perspective. Men are more likely to be in relatively high-paying, dangerous industries such as mining, construction, or manufacturing and to be represented by a union. Women, in contrast, are more likely to be in clerical jobs and to work in the service industry. These factors explain 53% of the wage gap. In 1998, adjusting for both differences in human capital and in industry, occupation, and unionism increases the size of American women's average earnings from 80% of American men's to 91%.

Claims of woman being "less willing" and having "less ability" to negotiate salaries and battle sexual discrimination are often attributed to being the cause of 25% to 40% of the wage gap. According to the European Commission however, direct discrimination only explains a small part of gender wage differences.

Effect of socialization

Another social factor, which is related to the aforementioned one, is the socialization of individuals to adopt specific gender roles. Job choices influenced by socialization are often slotted in to "demand-side" decisions in frameworks of wage discrimination, rather than a result of extant labor market discrimination influencing job choice. Men that are in non-traditional job roles or jobs that are primarily seen as a women-focused jobs, such as nursing, have high enough job satisfaction that motivates the men to continue in these job fields despite criticism they may receive.

Additionally, in the eyes of employees, women in middle management are perceived to lack the courage, leadership, and drive that male managers appear to have, despite female middle managers achieving results on par with their male counterparts in terms of successful projects and achieving results for their employing companies. These perceptions, along with the factors previously described in the article, contribute to the difficulty of women to ascend to the executive ranks when compared to men in similar positions.

Effect of pop culture

Gender roles are a key factor in the allocation of work to female and male employees, and societal ideas of gender roles stem somewhat from media influences. Media portrays ideals of gender-specific roles off of which gender stereotypes are built. These stereotypes then translate to what types of work men and women can or should do. Some common stereotypes include the ideas that managers should be males, or that pregnant women are a loss for the company after giving birth. In this way, gender plays a mediating role in work discrimination, and women find themselves in positions that do not allow for the same advancements as males.

Anti-discrimination legislation

According to the 2008 edition of the Employment Outlook report by the OECD, almost all OECD countries have established laws to combat discrimination on grounds of gender. Examples of this are the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Legal prohibition of discriminatory behavior, however, can only be effective if it is enforced. The OECD points out that:

"herein lies a major problem: in all OECD countries, enforcement essentially relies on the victims' willingness to assert their claims. But many people are not even aware of their legal rights regarding discrimination in the workplace. And even if they are, proving a discrimination claim is intrinsically difficult for the claimant and legal action in courts is a costly process, whose benefits down the road are often small and uncertain. All this discourages victims from lodging complaints."

Moreover, although many OECD countries have put in place specialized anti-discrimination agencies, only in a few of them are these agencies effectively empowered, in the absence of individual complaints, to investigate companies, take actions against employers suspected of operating discriminatory practices, and sanction them when they find evidence of discrimination.

In 2003, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that women in the United States, on average, earned 80% of what men earned in 2000 and workplace discrimination may be one contributing factor. In light of these findings, GAO examined the enforcement of anti-discrimination laws in the private and public sectors. In a 2008 report, GAO focused on the enforcement and outreach efforts of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Labor (Labor). GAO found that EEOC does not fully monitor gender pay enforcement efforts and that Labor does not monitor enforcement trends and performance outcomes regarding gender pay or other specific areas of discrimination. GAO came to the conclusion that "federal agencies should better monitor their performance in enforcing anti-discrimination laws."

In 2016, the EEOC proposed a rule to submit more information on employee wages by gender to better monitor and combat gender discrimination.

See also

- Equal Pay Day

- Equal pay for equal work

- Feminization of poverty

- Gender pay gap in India

- Glass ceiling

- Global Gender Gap Report

- Lowell Mill Girls

- Material feminism

- Motherhood penalty

For other wage gaps:

General:

References

- O'Brien, Sara Ashley (April 14, 2015). "78 cents on the dollar: The facts about the gender wage gap". CNN Money. New York. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

7% wage gap between male and female college grads a year after graduation even controlling for college major, occupation, age, geographical region and hours worked.

- Schwab, Klaus, et al. The Global Gender Gap Report 2015. World Economic Forum, 2015, pp. 8-9. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GGGR2015/cover.pdf. Accessed 29 Sept. 2016.

- Weichselbaumer, Doris; Winter-Ebmer, Rudolf (2005). "A Meta-Analysis on the International Gender Wage Gap" (PDF). Journal of Economic Surveys. 19 (3): 479–511. doi:10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00256.x.

- Stanley, T. D.; Jarrell, Stephen B. (1998). "Gender Wage Discrimination Bias? A Meta-Regression Analysis". The Journal of Human Resources. 33 (4): 962. doi:10.2307/146404. JSTOR 146404.

- Manning, Alan (2006). "The gender pay gap" (PDF). CentrePiece. 11 (1). Centre for Economic Performance: 13–16.

- Woolcock, Nicola. Women will earn the same as men – if they wait 150 years. The Sunday Times, July 28, 2006.

- Goodley, Simon (2011-08-31). "Women executives could wait 98 years for equal pay, says report". The Guardian. London. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

While the salaries of female executives are increasing faster than those of their male counterparts, it will take until 2109 to close the gap if pay grows at current rates, the Chartered Management Institute reveals.

- Chase, Max. "Female CFOs May Be Best Remedy Against Discrimination - CFO Insight". Cfo-insight.com. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - OECD. OECD Employment Outlook 2008 – Statistical Annex Archived December 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 358.

- "Frequently asked questions about pay equity". Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on April 22, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (2009), "The impact of a sustained gender wage gap on the economy" (PDF), Report to the Office for Women, Department of Families, Community Services, Housing and Indigenous Affairs: v–vi, archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2010

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency (2010), Pay Equity Statistics (PDF), Australian Government, archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2011

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Watson, Ian (2010). "Decomposing the Gender Pay Gap in the Australian Managerial Labour Market" (PDF). Australian Journal of Labour Economics. 13 (1). Macquarie University: 49–79. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Gender Differences in Employment and Why They Matter. World Development Report. The World Bank. 2011-09-12. pp. 198–253. doi:10.1596/9780821388105_ch5. ISBN 9780821388105.

- Larson, Paul D.; Morris, Matthew (2014). "Sex and salary: Does size matter? (A survey of supply chain managers)". Supply Chain Management: an International Journal. 19 (4): 385–394. doi:10.1108/SCM-08-2013-0268.

- For example, Alberta Human Rights Act, RSA 2000, c A-25.5 at §6 in Alberta and Pay Equity Act, RSO 1990, c P.7 in Ontario

- ^ Schwab, Klaus; Samans, Richard; Zahidi, Saadia; Bekhouche, Yasmina; Ugarte, Paulina Padilla; Ratcheva, Vesselina; Hausmann, Ricardo; Tyson, Laura D'Andrea (2015). The Global Gender Gap Report 2015 (PDF). World Economic Forum.

- ^ Yoon, Jayoung. "Labor Market Outcomes for Women in East Asia." Asian Journal of Women's Studies, vol. 21, no. 4, 2015, pp. 384-408.

- Jorge Mateo, Manauri (6 July 2016). "La banca aprovecha que en Dominicana hay más mujeres que hombres". Forbes México (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hausmann, Ricardo; Lauren D. Tyson; Saadia Zahidi (2009-01-01). The Global Gender Gap Report 2009. World Economic Forum. ISBN 9789295044289.

- ^ European Commission. The situation in the EU. Retrieved on July 12, 2011.

- Nupponen, Sakari. "Miehet painavat töitä niska limassa – naiset eivät". taloussanomat.fi. Taloussanomat. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "Tehtyjen työtuntien määrä on laskenut tasaisesti vuosina 1995-2005". tilastokeskus.fi. Tilastokeskus. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "Pay gap between men and women: MEPs call for binding measures to close it | News | European Parliament". News | European Parliament. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- "Wo liegen die Ursachen? - Europäische Kommission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2012-02-18.

- "Pressemitteilungen - Gender Pay Gap 2013 bei Vollzeitbeschäftigten besonders hoch - Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis)". Federal Statistical Office of German. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- "Beschäftigungsperspektiven von Frauen - Nur 2 Prozent Gehaltsunterschied". German Institute for Economic Research (in German). Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- "Gender Pay Gap: Wie groß ist der Unterschied wirklich?". Die Zeit. ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- "Studie: Geschlecht senkt Gehalt um sieben Prozent". Die Zeit. ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- CBS. "Krijgen mannen en vrouwen gelijk loon voor gelijk werk?". www.cbs.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "Women in their 20s earn more than men of same age, study finds". The Guardian. 28 August 2015.

- King, Mark (November 22, 2012). "Gender pay gap falls for full-time workers". The Guardian. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- "Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2012 Provisional Results". Office for National Statistics. 22 November 2012.

- "Highlights of women's earnings in 2013" (PDF). BLS Reports. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. December 2014.

- Thomson, Victoria (October 2006). "How Much of the Remaining Gender Pay Gap is the Result of Discrimination, and How Much is Due to Individual Choices?" (PDF). International Journal of Urban Labour and Leisure. 7 (2). Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- "Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2013 Provisional Results". Ons.gov.uk.

- "Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings: 2015 Provisional Results". Office of National Statistics.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Equality Act 2010 (Equal Pay Audits) Regulations 2014

- "Women in their 20s earn more than men of same age, study finds". The Guardian. 29 August 2015.

- "PAYnotes on Gender Pay Reporting – What employers need to know". Paydata Ltd. February 26, 2016.

- Alfarhan, Usamah F. (2015). "Gender Earnings Discrimination in Jordan: Good Intentions Are Not Enough". International Labour Review. 154 (4): 563–580. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2015.00252.x.

- Fyodor Tertitskiy (23 December 2015). "Life in North Korea - the adult years". the Guardian. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- "Women's earnings as a percentage of men's, 1979-2005 : The Economics Daily : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- United States Congress Joint Economic Committee. Graph: Federal Workforce – Gender Pay Gap Unchanged. Retrieved on March 31, 2011.

- Blau, F. D.; Kahn, L. M. (1 October 2006). "The U.S. Gender Pay Gap in the 1990S: Slowing Convergence". ILR Review. 60 (1): 45–66. doi:10.1177/001979390606000103.

- ^ Francine D. Blau; Lawrence M. Kahn. "The Gender Pay Gap – Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?" (PDF). Academy of Management Perspectives. 21 (1). Stanford University: 7–23. doi:10.5465/AMP.2007.24286161.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2012. Current Population Reports, P60–245, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2013, p. 5.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009. Current Population Reports, P60–238, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2010, p. 7.

- Institute for Women's Policy Research. The Gender Wage Gap: 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Pay Equity & Discrimination". Institute for Women's Policy Research.

- Agness, Karin. "Don't Buy Into The Gender Pay Gap Myth". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- "An Analysis of Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women" (PDF). Consad.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2013. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Kanter, Rosabeth Moss (4 August 2008). Men and Women of the Corporation. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-0-7867-2384-3.

- Office of the White House, Council of Economic Advisors, 1998, IV. Discrimination

- Levine, Report for Congress, "The Gender Gap and Pay Equity: Is Comparable Worth the Next Step?", Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2003

- ^ "Justice Talking: The Women's Equality Amendment / What Does It Mean and Is It Necessary?". 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ^ United States Congress Joint Economic Committee. Invest in Women, Invest in America: A Comprehensive Review of Women in the U.S. Economy. Washington, DC, December 2010.

- ^ Shelley J. Correll; Stephen Benard; In Paik. "Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty?". American Journal of Sociology. 112 (5date=March 2007). The University of Chicago Press: 1297–1339. JSTOR 10.1086/511799.

- Rouse, Goldin C (2000). "Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of blind auditions on female musicians" (PDF). The American Economic Review 90(4): 715-41.

- Wendy M. Williams. "National hiring experiments reveal 2:1 faculty preference for women on STEM tenure track". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112: 5360–5365. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418878112. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- Sarah Kaplan (14 April 2015). "Study finds, surprisingly, that women are favored for jobs in STEM". Washington Post. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- "Fallacy of the Gender Wage Gap". Payscale. April 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- Kelsey, Cherly Lynn. "Gender Inequality:Empowering Women" (PDF).

- European Commission (March 4, 2011). "Closing the gender pay gap". Archived from the original on March 6, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Women in their 20s earn more than men of same age, study finds". American Association of University Women.

- Christianne Corbett; Catherine Hill (October 2012). "Graduating to a Pay Gap: The Earnings of Women and Men One Year after College Graduation" (PDF). Washington, DC: American Association of University Women.

- Bassett, Laura (October 24, 2012), "Closing The Gender Wage Gap Would Create 'Huge' Economic Stimulus, Economists Say", Huffington Post, citing

- Becker, Gary (1993). "Nobel Lecture: The Economic Way of Looking at Behavior". Journal of Political Economy. 101 (3): 387–389. doi:10.1086/261880. JSTOR 2138769.

- Cain, Glen G. (1986). "The Economic Analysis of Labor Market Discrimination: A Survey". In Ashenfelter, Orley; Laynard, R. (eds.). Handbook of Labor Economics: Volume I. pp. 710–712. ISBN 9780444534521.

- Ransom, Michael; Oaxaca, Ronald L. (January 2005). "Intrafirm Mobility and Sex Differences in Pay" (PDF). Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 58 (2). Sage Publications. JSTOR 30038574.

- Congress, C. L. (n.d.). Women in the Workforce: Still a Long Way from Equality. Retrieved November 23, 2012, from Canadian Labour Congress.

- Blau, Francine (2015). "Gender, Economics of". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition). Elsevier.

- CONSAD Research Corporation, An Analysis of Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2013

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Patten, Eileen (April 14, 2015). "On Equal Pay Day, key facts about the gender pay gap". Pew Research Center.

- Francine D. Blau; Lawrence M. Kahn. "The Gender Pay Gap – Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?" (PDF). Academy of Management Perspectives. 21 (1). Stanford University: 7–23. doi:10.5465/AMP.2007.24286161.

- European Commission. "Tackling the gender pay gap in the European Union" (PDF). Justice. ISBN 978-92-79-36068-8.

- "What are the causes? - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- Mooney Marin, Margaret; Fan, Pi-Ling (1997). "The Gender Gap in Earnings at Career Entry". American Sociological Review. 62 (4): 589–591. doi:10.2307/2657428. JSTOR 2657428.

- Jacobs, Jerry (1989). Revolving Doors: Sex Segregation and Women's Careers. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804714891.

- Reskin, Barbara (1993). "Sex Segregation in the Workplace". Annual Review of Sociology. 19: 248. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.19.1.241. JSTOR 2083388.

- Macpherson, David A.; Hirsch, Barry T. (1995). "Wages and Gender Composition: Why do Women's Jobs Pay Less?". Journal of Labor Economics. 13 (3): 460. doi:10.1086/298381. JSTOR 2535151.

- Ruth Simpson (2006). "Men in non-traditional occupations: Career entry, career orientation and experience of role strain". Human Resource Management International Digest. 14 (3). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.426.5021. doi:10.1108/hrmid.2006.04414cad.007 – via citeseerx.ist.psu.edu.

- Martell, Richard F., et al. "Sex Stereotyping In The Executive Suite: 'Much Ado About Something'." Journal Of Social Behavior & Personality 13.1 (1998): 127-138. Academic Search Complete. Web. 20 Sept. 2016.

- Frankforter, Steven A. "The Progression Of Women Beyond The Glass Ceiling." Journal Of Social Behavior & Personality 11.5 (1996): 121-132. Academic Search Complete. Web. 20 Sept. 2016.

- ^ Tharenou, Phyllis (2012-10-07). "The Work of Feminists is Not Yet Done: The Gender Pay Gap—a Stubborn Anachronism". Sex Roles. 68 (3–4): 198–206. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0221-8. ISSN 0360-0025.

- Bryant, Molly (2012). "Gender Pay Gap". Iowa State University Digital Repository.

- Castagnetti, C.; Rosti, L. (2013-09-19). "Unfair Tournaments: Gender Stereotyping and Wage Discrimination among Italian Graduates". Gender & Society. 27 (5): 630–658. doi:10.1177/0891243213490231. ISSN 0891-2432.

- Tharenou, Phyllis (2013). The Work of Feminists is Not Yet Done: The Gender Pay Gap—a Stubborn Anachronism

- ^ OECD. OECD Employment Outlook – 2008 Edition Summary in English. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 3–4.

- OECD. OECD Employment Outlook. Chapter 3: The Price of Prejudice: Labour Market Discrimination on the Grounds of Gender and Ethnicity. OECD, Paris, 2008.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Women's Earnings: Federal Agencies Should Better Monitor Their Performance in Enforcing Anti-Discrimination Laws. Retrieved on April 1, 2011.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Report Women's Earnings: Federal Agencies Should Better Monitor Their Performance in Enforcing Anti-Discrimination Laws.

- "Written Testimony of Jocelyn C. Frye Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress." 2016, p. 3.

External links

- Gender pay gap statistics by Eurostat of the European Commission

- UK Gender Salary Comparisons for Graduates 6 months after leaving University. (Based on over 650,000 students)

- Race and gender in the labor market Joseph G. Altonji and Rebecca M. Blank. Handbook of labor economics 3 (1999): 3143-3259.