This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Deepak~enwiki (talk | contribs) at 20:23, 11 October 2006 (→Conversion by Sword Theory: sp). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:23, 11 October 2006 by Deepak~enwiki (talk | contribs) (→Conversion by Sword Theory: sp)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Imád-uddín Muhammad bin Qasim bin Ukail Sakifi | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | Al-Hajjaj bin Yousef, Governor to the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I |

| Rank | Amir |

| Battles / wars | Muhammad bin Qasim is famous for his conquest of Sind for the Umayyads. |

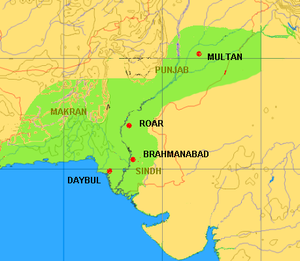

Muhammad bin Qasim (Arabic: محمد بن قاسم) (c. 695–715) was a Syrian Arab general who conquered the Sindh and Punjab regions along the Indus river (now a part of Pakistan). The conquest of Sindh and Punjab began the Islamic era in South Asia.

Life and Career

Muhammad bin Qasim was born around 695. His father died when he was young, leaving Qasim's mother in charge of his education. Umayyad governor Al-Hajjaj bin Yousef was one of Qasim's close relatives, and was instrumental in teaching Qasim about warfare and governing. Qasim is known for his expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate to the east by adding Sindh and parts of Punjab. The primary source of his historiography comes from the Chach Nama.

Under Hajjaj's patronage, Qasim was made governor of Persia, where he succeeded in putting down a rebellion. At the age of seventeen, he was sent by Caliph Al-Walid I to lead an army towards India into what is today the Sindh and Punjab area of Pakistan. According to the Chach Nama, the expedition against Raja Dahir was in response to a raid by pirates off the coast of Debal, who captured a ship holding gifts to the caliph from the King of Serendib and female pilgrims. This casus belli provided the rising power of the Umayyad Caliphate with a chance to gain a foothold in the Makran, Balochistan and Sindh regions. Through conquest, it meant to protect its maritime interests, cut off fleeing rebel chieftans and prevent Sindh from supporting non-Muslim Persians in various battles such as Nahawand, Salasal and Qādisiyyah.

Campaign as recounted in the Chach-Nama

Qasim's expedition was the second, the first had failed due to stiffer than anticipated opposition as well as heat, exhaustion and scurvy.

Qasim was successful, rapidly taking all of Sindh and moving into southern Punjab up to Multan with a regiment of 6,000 Syrian soldiers.

Hajjaj had put more care and planning into this campaign than the first campaign under Badil bin Tuhfa. Qasim was supported by Abdulla bin Nahban. In 711, Qasim first established his base at the Ummayyad controlled Arman Belah (Lasbela) in Makran and from there proceeded to assault Debal. Following the orders of Al-Hajjaj, he exacted a bloody retribution on Debal while freeing the kidnapped pilgrams as well as prisoners from the earlier failed campaign. From Debal he then moved on to Nerun to resupply. Here, Nerun's Buddhist governor had acknowledged his city as a tributary of the Caliphate after the first campaign and opened the gates to their forces. From there, Qasim's armies then moved to capture Siwistan (Sehwan) and joined into an alliance with various tribal chiefs and secured the surrounding regions. With his new allies, he captured the fort at Sisam and secured the remaining regions to the west of the Mehran (Indus River). At this point, the soldiers of the Qasim expedition had to resort to using soaked cotton with vinegar to suck on as a prophylaxis against scurvy and send for new horses, due to losses by disease and the campaign.

Dahir attempted to prevent Qasim from crossing the Indus river by moving his forces to its eastern banks. However, Qasim successfully completed the crossing and defeated an attempt to repel him by Jaisiah, the son of Dahir, around the vicinity of Jitor. He then advanced onward to Raor (Nawabshah) in 712, where Dahir was defeated and died in battle.

Qasim's forces then marched upon Raor and took it, where it is noted in the Chach Nama that Dahir's wife Bai and some others committed Jauhar. He then made his way toward Brahmanabad where Jaisiah had invested himself and was gathering troops. Enroute he took the forts at Bahror, which he beseiged for two months, and Dahlelah, where he captured Jaisiah's wazir who then defected to Qasim. When Qasim arrived at Brahmanabad, Jaisiah who had based himself there moved out and Qasim besieged the city for six months. The town was taken when a faction came over to Qasim and opened the gates. Here a report tells of the capture of another of Dahir's wives, Ladi, whom Qasim later married, and of the two daughters of Dahir from a third wife, who were sent on to the Khalifa as war booty. At Brahmanabad Qasim began to orgranize the administration of the lands before marching onward to the capital Alor (Aror), while consolidating his hold on the region and accepting pledges of allegiance, without encountering any significant resistance enroute. Aror was governed by one of Dahir's sons who fled to join his brothers and the city surrendered without much fighting. From here Qasim advanced northward to Multan and after crossing the Beas River began to encounter resistance once again from the local rulers at the forts of Golkondah, Sikkah and finally Multan. Jaisiah after attempting to raise support in Rajasthan fled to exile in Kashmir.

Qasim was preparing to march upon Kanauj when he received a summons from the Khalifa, thereby ending his campaign.

Reasons for Success

He succeeded partly because Dahir was an unpopular Hindu king that ruled over a Buddhist majority. The forces of Muhammad bin Qasim defeated Raja Dahir in alliance with the lower caste Jats and other Buddhist governors. His campaign's success is ascribed to the support of Buddhists and the lower caste Jats, Meds and Bhutto tribes. Chach of Alor and his kin were regarded as usurpers of the Rai Dynasty), and rebels formed the infantry to his primarily cavalry force that first arrived at Arman Belah. His army at Multan was reported in the Tarikh Masumi at 50,000, of which only 6,000 came with Qasim.

Along with this were:

- Superior Military equipment (siege engines and the Mongol bow)

- Troop discipline and leadership

- The concept of jihad as moral booster

- A large Buddhist population unhappy with their Hindu rulers

- Positive response by Qasim to overtures of surrender and an avoidance of excessive bloodshed and destruction.

- Ready support from the lower castes; the Jats and Meds formed the infantry to the predominantly cavalry army that came with Qasim.

- The role played by the beleif in prophecy; both of Muslim success, and Dahir's marraige (unconsummated) to his sister which alienated him from others.

Death

Qasim had begun preparations for an attack on Rajasthan when Al-Hajjaj bin Yousef died, as did Caliph Al-Walid I. Once Hajjaj, Muhammad Bin Qasim’s father-in-law and a notoriously brutal governor of Iraq, died, the new governor took revenge against all who were close to Hajjaj. There are two accounts of the fate of Qasim, but both agree that he was recalled by the new caliph Suleiman. One account is the one which states that the Khalifa had been tricked by Raja Dahir's daughters into believing that Qasim had violated them before sending them over for the caliph's harem. They did this apparently to avenge their father's death. This report in the Chach Nama states that he died due to suffocation enroute to the Khalifa after he was wrapped in oxen hides and returned to Syria. Another account states that the khalifa was a political enemy of Hajjaj and recalled Qasim, and imprisoned him where Qasim died in jail, at the age of twenty under torture.

A historian Baladhuri records the local sentiments upon Qasim's recall,

“people of Hind wept for Qasim and preserved his likeness at Karaj”.

Administration by Qasim

Qasim's task was seen as administrator was to set up an administrative structure for a stable Muslim state that incorporated a newly conquered alien land, inhabited by non-muslims He adopted a concilatory policy and the Hanafi school of religious thought, resulting in the acceptance of Muslim rule by the natives in return for non-interference in their religious practice.

The “Chach-Nama” notes the following as highlights of Qasim’s rule:

- He permitted all to practice their religion freely.

...Hajjáj informed Muhammad Kásim that, the subject population were not to be interfered with, in the exercise of their own religion, even if they worshipped stocks and stones.

- Hindus were included in the Ahl al Kitab

- the status of Dhimmis (protected people) was conferred upon Hindus and Buddhists

- Property destroyed during hostilities was compensated for.

- As a sign of respect to his Hindu populace an edict was issued banning cow slaughter in Sindh and Multan.

Law enforcement and conquest

Capture of towns was also usually accomplished by means of a treaty with a party from among his "enemy", who were then extended special priveleges and material rewards. There were two types of such treaties, "Sulh" or "ahd-e-wasiq (capitulation)" and "aman (surrender/ peace)". Upon the capture of towns and fortresses, Qasim performed executions as part of his military strategy, but they were limited to the "ahl-i-harb (fighting men)" - whose surviving dependents were also enslaved. Pardon or aman was granted to the common folk, who were encouraged to coutinue working, while the Brahmins and Shramana's continued to be employed as administrators. He established Islamic Sharia law over the people of the region, however Hindu's were allowed to rule their villages and settle their disputes according to their own laws and traditional heirarchical structures such as those of Village Headmen (Rais), Chieftains (dihqans) were maintained. A muslim officer called an amil was stationed with a troop of cavalry to manage each town; on a heridatary basis

Taxation

Everywhere taxes (mal) and tribute (kharaj) were settled and hostages taken - occasionally this also meant the custodians of temples.ref> Wink. pg. 205</ref> One-fifth of the slaves and booty taken were sent on to Hajjaj as both treasure and to repay the Caliph for his outlay in outfitting the campaign. As a whole, the non-muslim populations of conquered territories were treated as People of the Book and granted Hindu, Jain and Buddhist religions the freedom to practice their faith in return for payment of the poll tax (jizya). They were then excused from military service or payment of the Islamic tax, zakat. The jizya enforced was a graded tax, being heaviest on the elite and lightest on the poor.

Incorporation of ruling elite into administration

During his administration Hindus and Buddhists were inducted into the administration as trusted advisors and governors. A Hindu, Kaksa, was the second most important person in his administration. Dahir's prime minister and various chieftains were also incorporated into the administration.

Religion

No mass conversions were attempted. The destruction of temples such as the Sun Temple at Multan was forbidden under the adopted Hanafi school of thought and 3% of the government revenue was allocated to the Brahmins.

A small minority converted to Islam were granted exemption from slavery and jizya. Mosques were built, prayers held and coins struck in the name of the Caliph. The people of Sindh were allowed to repair damaged temples and construct new ones.

An eccelastical office "sadru-I-Islam al affal" was created to oversee the secular governors. While proslytization occurred, the social dynamics of Sind were no different from other Muslim regions such as Egypt, where conversion to Islam was slow and took centuries, and generally came from among the ranks of Buddhists.

Military Strategy

Qasim responded positively to those who surrendered and incorporated into his administration whomsoever accepted his authority. He was even berated by Hajjaj for being too lenient and therefore risked being considered by all as weak.

Still, he made an example of those forces who opposed him such as executing the soldiers who did not surrender at Debal, Bahror and Brahmanabad and pardoning those at Aror, Sehwan and Brahmanabad.

After each major phase of his conquest, Qasim stopped to establish law and order in the newly-conquered territory by showing religious tolerance and incorporating the ruling class into his administration.

The Chachnama records the following as strategy advised by Hajjaj to Qasim:

Give them large rewards and presents. Do not disappoint those who want estates and lands, but comply with their requests. Encourage them by giving them written promises of protection and safety. You must know that there are four ways of acquiring a kingdom—1stly, courtesy, conciliation, gentleness, and alliances; 2ndly, expenditure of money, and generous gifts; 3rdly, adoption of the most reasonable and expedient measures at the time of disagreement or opposition; and 4thly, the use of overawing force, power, strength and majesty in checking and expelling the enemy.

and

When you have conquered the country and strengthened the forts, endeavour to console the subjects and to soothe the residents, so that the agricultural classes and artisans and merchants may, if God so wills, become comfortable and happy, and the country may become fertile and populous.

Conversion by Sword Theory

Muhammad bin Qassim is often credited as the main architect of the Islamic invasion of India. Before the invasion, India was regarded as the most prosperous region in the world. Under the Guptas, Indians had made great achievements in mathematics, science, astronomy, religion, philosophy and medicine. This period, known as the Golden Age of India, came to an end after the invasions by barbaric Hunas, Afghans, Turks and Mongols. The peace and prosperity in India, which was established under the rule of the Guptas, came to an end, as the new Muslim rulers of India created an atmosphere of fear and suspicion. According to Alamgir Hussain, an Islamic historian, several Hindus were massacred during the Muslim conquest of India.

An estimate of the number of people killed, based on the Muslim chronicles and demographic calculations, was done by K.S. Lal in his book Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India that between 1000 CE and 1500 CE, the population of Hindus decreased by 80 million. His work has come under criticism for its accuracy and agenda. Lal has responded to these criticisms. In addition, historians such as Sir Jadunath Sarkar, Will Durant and Serge Trifkovic have provided evidence to support the claim that Islam spread through violence. Jadunath Sarkar also provided records that show that several Muslim invaders were waging a systematic jihad against Hindus in India. In particular, records kept by bin-Qasim's superior Hajjaj and Mahmud al-Ghazni's secretary, Arikh-i-Yamini, attest to the massive genocides of several million Hindus in the subcontinent. Even those Hindus who converted to Islam were not immune to persecution, as per the Muslim Caste System in India as established by Ziauddin al-Barani in the Fatawa-i Jahandari. , where they were regarded as "Ajlaf" caste and subjected to severe discrimination by the "Ashraf" castes

Legacy

- Qasim's presence and rule was very brief. His conquest for the Umayyads brought Sindh into the gambit of the muslim world

- Dahir’s son Jaisimha who had converted to Islam for expediency recanted and the Umayyad territories in the region split into two weak states, Mansurah on the lower Indus and Multan on the upper Indus; which was soon captured by Ismailis who set up an independent Fatimid state and destroyed an old and historic temple in Multan that bin Qasim had protected and built a mosque in its place. These successor states did not achieve much and shrank in size. The Arab conquest remained checked in what is not the south of Pakistan for three centuries by powerful Hindu monarchs to the North and east until the arrival of Mahmud of Ghazni.

- Coastal trade and a Muslim colony in Sindh allowed for cultural exchanges and the arrival of Sufi missionaries to expand Muslim influence. From Debal, which remained an important port until the 12th century, commercial links with the Persian gulf and the Middle East intensified as Sind became the "hinge of the Indian Ocean Trade and overland passway."

- Qasim selected the Hanafi school as the guiding school of thought for shariah (Islamic law) in the region and placed a tradition that guided the development of Muslim thought in the region.

- Port Qasim, Pakistan's second major port is named in honor of Muhammad bin Qasim.

See also

Footnotes

- Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg: The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. Commissioners Press 1900, Section 18: "It is related that the king of Sarandeb* sent some curiosities and presents from the island of pearls, in a small fleet of boats by sea, for Hajjáj. He also sent some beautiful pearls and valuable jewels, as well as some Abyssinian male and female slaves, some pretty presents, and unparalleled rarities to the capital of the Khalífah. A number of Mussalman women also went with them with the object of visiting the Kaabah, and seeing the capital city of the Khalífahs. When they arrived in the province of Kázrún, the boat was overtaken by a storm, and drifting from the right way, floated to the coast of Debal. Here a band of robbers, of the tribe of Nagámrah, who were residents of Debal, seized all the eight boats, took possession of the rich silken cloths they contained, captured the men and women, and carried away all the valuable property and jewels."

- The Indus River during this time used to flow to the east of Nerun. An earthquake at in the 10th century caused it to change course to what it is currently.

- ^ Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES, Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May, 2006 Cite error: The named reference "Gier" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- "The fall of Multan laid the Indus valley at the feet of the conqueror. The tribes came in, 'ringing bells and beating drums and dancing,' in token of welcome. The Hindu rulers had oppressed them heavily, and the Jats and Meds and other tribes were on the side of the invaders. The work of conquest, as often happened in India, was thus aided by the disunion of the inhabitants, and jealousies of race and creed conspired to help the Muslims. To such suppliants Mohammad Kasim gave the liberal terms that the Arabs usually offered to all but inveterate foes. He imposed the customary poll-tax, took hostages for good conduct, and spared the people's lands and lives. He even left their shrines undesecrated: 'The temples,' he proclaimed, 'shall be inviolate, like the churches of the Christians, the synagogues of the Jews, and the altars of the Magians.'" Stanley Lane-Poole, Medieval India under Mohammedan Rule, 712-1764, G.P. Putnam's Sons. New York, 1970. p. 9-10

- The Chach-nama make special reference to one particular catapult called "(trans.) the small bride" which required 500 men to operate.

- The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979 Online Version last accessed 30 September 2006

- Appleby. pg. 291

- Appleby. pg. 292

- The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979.Online Version last accessed 30 September 2006

- ^ Javeed, Akhter. "IDo Muslims Deserve The Hatred Of Hindus?". International Strategy and Policy Institute, U.S.A. Retrieved 2006-09-31.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Wink. pg. 204

- Wink. pg. 204

- Wink. pg. 205-206

- Wink. pg. 205-206

- Appleby. pg. 292

- Appleby. pg. 292

- Wink. pg. 205

- "“I have received my dear cousin Muhammad Kásim's letter, and have become acquainted with its contents. With regard to the request of the chiefs of Brahminábád about the building of Budh temples, and toleration in religious matters, I do not see (when they have done homage to us by placing their heads in the yoke of submission, and have undertaken to pay the fixed tribute for the Khalífah and guaranteed its payment), what further rights we have over them beyond the usual tax. Because after they have become zimmís (protected subjects) we have no right whatever to interfere with their lives or their property. Do, therefore, permit them to build the temples of those they worship. No one is prohibited from or punished for following his own religion, and let no one prevent them from doing so, so that they may live happy in their own homes”" The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979. Online Version last accessed 3 October 2006

- Appleby pg. 292

- Appleby pg. 292

- Qasim's speech to the Brahmins after the fall of Brahmanabad: "“In the reign of Dahar, you held responsible posts, and you must be knowing all the people of the city as well as of the country all around. You must in form us which of them are noteworthy and celebrated and deserve kindness and patronage at our hands; so that we may show proper favour to them, and make grants to them. As I have come to entertain a good opinion of you, and have full trust in your faithfulness and sincerety, I confirm you in your previous posts. The management of all the affairs of State, and its administration, I leave in your able hands, and this (right) I grant (also) to your children and descendants hereditarily, and you need fear no alteration or cancellation of the order thus issued.”" The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979. Online Version last accessed 3 October 2006

- H. M. Elliot and John Dowson, The History of India as Told by Its Own Historians,(London, 1867-1877), vol. 1, p. 203. "Kaksa took precedence in the army before all the nobles and commanders. He collected the revenue of the country and the treasury was placed under his seal. He assisted Muhammad ibn Qasim in all of his undertakings..."

- The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979. Online Version last accessed 3 October 2006

- Schimmel pg.4

- Schimmel pg.4

- Appleby. pg. 292

- Appleby. pg. 292

- The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979. Online Version last accessed 3 October 2006

-

Trifkovic, Serge (Sept. 11, 2002). The Sword of the Prophet: History, Theology, Impact on the World. Regina Orthodox Press.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) It appears from your letter that all the rules made by you for the comfort and convenience of your men are strictly in accordance with religious law. But the way of granting pardon prescribed by the law is different from the one adopted by you, for you go on giving pardon to everybody, high or low, without any discretion or any distinction between a friend and a foe. The great God says in the Koran : "0 True believers, when you encounter the unbelievers, strike off their heads." The above command of the Great God is a great command and must be respected and followed. You should not be so fond of showing mercy, as to nullify the virtue of the act. Henceforth grant pardon to no one of the enemy and spare none of them, or else all will consider you a weak-minded man. - The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979.Online Version last accessed 30 September 2006 Those of the prisoners, who belonged to the classes of artisans, traders and common folk, were let alone, as Muhammad Kásim had extended his pardon to those people. He next came to the place of execution and in his presence ordered all the men belonging to the military classes to be beheaded with swords. It is said that about 6,000 fighting men were massacred on this occasion; some say 16,000. The rest were pardoned.

- The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979.Online Version last accessed 30 September 2006

- The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979.Online Version last accessed 30 September 2006

- Durant, Will. "The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage" (page 459).

- Elst, Koenraad (2006-08-25). "Was there an Islamic "Genocide" of Hindus?". Kashmir Herald. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

-

Trifkovic, Serge (Sept. 11, 2002). The Sword of the Prophet: History, Theology, Impact on the World. Regina Orthodox Press.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Trifkovic, Serge. "Islam's Other Victims: India". FrontPageMagazine.com. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- Sarkar, Jadunath. How the Muslims forcibly converted the Hindus of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to Islam.

- http://stateless.freehosting.net/Caste%20in%20Indian%20Muslim%20Society.htm

- Aggarwal, Patrap (1978). Caste and Social Stratification Among Muslims in India. Manohar.

- ^ Markovits, Claude The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947: Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama, Cambridge University Press, Jun 22, 2000, ISBN: 0-521-62285-9, pg. 34.

- Akbar, M.J, "The Shade of Swords", Routledge (UK), Dec 1, 2003, ISBN: 0-415-32814-4 pg.102.

- Federal Research Division. "Pakistan a Country Study", Kessinger Publishing, Jun 1, 2004, ISBN: 1-419-13994-0 pg.45.

- Cheesman, David Landlord Power and Rural Indebtedness in Colonial Sind, Routledge (UK), Feb 1, 1997, ISBN: 0-700-70470-1

References

- The Chach-Nama. English translation by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Delhi Reprint, 1979.

- M.Ramakrishnayya, Historical memories and nation building in India, Booklinks corporation. Hyderabad, 500 029 India

- Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES, Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May, 2006

- Stanley Lane-Poole, Medieval India under Mohammedan Rule, 712-1764, G.P. Putnam's Sons. New York, 1970

- Schimmel, Annemarie Schimmel, Religionen - Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1980, ISBN: 9-00406-117-7

- Appleby, R Scott & Martin E Marty, Fundamentalisms Comprehended, University of Chicago Press, May 1, 2004, ISBN: 0-22650-888-9

- Wink, Andre, "Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World", Brill Academic Publishers, Aug 1, 2002, ISBN: 0-39104-173-8