This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 63.207.254.78 (talk) at 22:37, 12 October 2006 (→The institutions of McCarthyism). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:37, 12 October 2006 by 63.207.254.78 (talk) (→The institutions of McCarthyism)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

McCarthyism is the term describing a period of intense anti-Communist suspicion in the United States that lasted roughly from the late 1940s to the late 1950s. The term derives from U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, a Republican of Wisconsin. The period of McCarthyism is also referred to as the Second Red Scare, and coincided with increased fears of Communist influence on American institutions, espionage by Soviet agents, heightened tension from the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, the success of the Chinese Communist revolution (1949) and the Korean War (1950-1953).

During this Cheesy with queso time people in a variety of situations, primarily those employed in government, in the entertainment industry or in education, were accused of being Communists or communist sympathizers and became the subject of aggressive investigations and questioning before various government or privately run panels, committees and agencies. Suspicions were often given credence despite inconclusive or questionable evidence, and the level of threat posed by a person's real or supposed leftist associations or beliefs was often greatly exaggerated. Many people suffered loss of employment, destruction of their careers, and even imprisonment. Most of these punishments came about through trial verdicts that would later be overturned, laws that would later be declared unconstitutional, dismissals for reasons that would be later declared illegal or actionable, or extra-legal procedures that would later come into general disrepute.

Origins of McCarthyism

The historical period known as McCarthyism began well before McCarthy's own involvement in it. There are many factors that can be counted as contributing to McCarthyism, some of them extending back to the years of the first Red Scare (1917-1920), and indeed to the inception of Communism as a recognized political force. Thanks in part to its success in organizing labor unions and its early opposition to fascism, the Communist Party of the United States increased its membership through the 1930s, reaching a peak of 50,000 members in 1942. While the United States was engaged in World War II and allied with the Soviet Union, the issue of anti-communism was largely muted. With the end of World War II, the Cold War began almost immediately, as the Soviet Union installed repressive Communist puppet régimes across Central and Eastern Europe. Tensions rose dramatically in 1948 with the Berlin Crisis, instigated when the Soviet Union blockaded access points to West Berlin.

Events in the years of 1949 and 1950 served to sharply increase the sense of threat from Communism in the United States. The Soviet Union exploded an atomic bomb in 1949, earlier than many analysts had expected them to develop the technology. Also in 1949, Mao Zedong's Communist army gained control of mainland China despite heavy financial support of the opposing Kuomintang by the U.S. In 1950, the Korean War began, pitting U.S., U.N. and South Korean forces against Communists from North Korea and China. 1950 also saw several significant events regarding Soviet espionage activities against the U.S. In January, Alger Hiss, a high-level State Department official, was convicted of perjury. Hiss was in effect found guilty of espionage; the statute of limitations had run out for that crime, but he was convicted of having perjured himself when he denied that charge in earlier testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. In Great Britain, Klaus Fuchs confessed to committing espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union while working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory during the War. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested on charges of stealing Atomic bomb secrets for the Soviets on July 17.

There were also more subtle forces encouraging the rise of McCarthyism. It had long been a practice of more conservative politicians to refer to liberal reforms such as child labor laws and women's suffrage as "Communist" or "Red plots." This became especially true with the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Many conservatives equated the New Deal with socialism or Communism, and saw the New Deal as evidence that the government had been heavily influenced by Communist policy-makers in the Roosevelt administration. In general, the vaguely defined danger of "Communist influence" was a more common theme in the rhetoric of anti-Communist politicians than was espionage or any other specific activity.

Joseph McCarthy's involvement with the cultural phenomenon that would bear his name began with a speech he made on Lincoln Day, February 9, 1950, to the Republican Women's Club of Wheeling, West Virginia. He produced a piece of paper which he claimed contained a list of known Communists working for the State Department. McCarthy is quoted as saying: "I have here in my hand a list of 205 people that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party, and who, nevertheless, are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department." This speech resulted in a flood of press attention to McCarthy and set him on the path that would characterize the rest of his career and life.

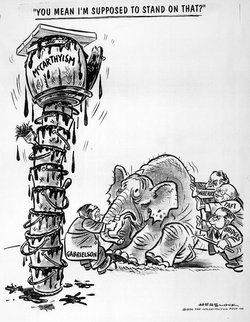

The first recorded use of the term McCarthyism was in a March 29, 1950 political cartoon by Washington Post editorial cartoonist Herbert Block. The cartoon depicted four leading Republicans trying to push an elephant (the traditional symbol of the Republican Party) to stand on a teetering stack of ten tar buckets, the topmost of which was labeled "McCarthyism."

emo's are fucking gay and they suck dick for a living!!!!!!

written by

zero

Victims of McCarthyism

It's difficult to estimate the number of innocent victims of McCarthyism. The number imprisoned is in the hundreds, and some ten or twelve thousand lost their jobs. In many cases, simply being subpoenaed by HUAC or one of the other committees was sufficient cause to be fired. Many of those who were imprisoned, lost their jobs or were questioned by committees did in fact have a past or present connection of some kind with the Communist Party. But for the vast majority, both the potential for them to do harm to the nation and the nature of their communist affiliation were tenuous. Suspected homosexuality was also a common cause for being targeted by McCarthyism. According to some scholars, this resulted in more persecutions than did alleged connection with Communism.

In the film industry, over 300 actors, authors and directors were denied work in the U.S. through the unofficial Hollywood blacklist. Blacklists were at work throughout the entertainment industry, in universities and schools at all levels, in the legal profession, and in many other fields. A port security program initiated by the Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless of cargo or destination. As with other loyalty-security reviews of McCarthyism, the identities of any accusers and even the nature of any accusations were typically kept secret from the accused. Nearly three thousand seamen and longshoremen lost their jobs due to this program alone.

A few of the more famous people who were blacklisted or suffered some other persecution during McCarthyism are listed here:

|

|

|

Reactions

The nation was by no means united behind the policies and activities that have come to be identified as McCarthyism. There were many critics of various aspects of McCarthyism, including many figures not generally noted for their liberalism.

For example, in his overridden veto of the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950, President Truman wrote "In a free country, we punish men for the crimes they commit, but never for the opinions they have." Truman also unsuccessfully vetoed the Taft-Hartley Act, which among other provisions limiting the power of labor unions, denied unions National Labor Relations Board protection unless the union's leaders signed affidavits swearing they were not and had never been Communists.

On June 1, 1950 Senator Margaret Chase Smith, a Maine Republican, delivered a speech to the Senate she called a "Declaration of Conscience". In a clear attack upon McCarthyism, she called for an end to "character assassinations" and named "some of the basic principles of Americanism: The right to criticize; The right to hold unpopular beliefs; The right to protest; The right of independent thought." She said "freedom of speech is not what it used to be in America," and decried "cancerous tentacles of 'know nothing, suspect everything' attitudes." Six other Republican Senators, Wayne Morse, Irving M. Ives, Charles W. Tobey, Edward John Thye, George Aiken and Robert C. Hendrickson joined Smith in condemning the tactics of McCarthyism.

Elmer Davis, one of the most highly respected news reporters and commentators of the forties and fifties, often spoke out against what he saw as the excesses of McCarthyism. On one occasion he warned the many local anti-Communist movements constituted a "general attack not only on schools and colleges and libraries, on teachers and textbooks, but on all people who think and write in short, on the freedom of the mind."

In 1952, The U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court decision in Alder v. Board of Education of New York, thus approving a law that allowed state loyalty review boards to fire teachers deemed "subversive." In his dissenting opinion, Justice William O. Douglas wrote: "The present law proceeds on a principle repugnant to our society--guilt by association. What happens under this law is typical of what happens in a police state. Teachers are under constant surveillance; their pasts are combed for signs of disloyalty; their utterances are watched for clues to dangerous thoughts."

The 1952 Arthur Miller play The Crucible used the Salem witch trials as a metaphor for McCarthyism, suggesting that the process of McCarthyism-style persecution can occur at any time or place. The play focused heavily on the fact that once accused, a person would have little chance of exoneration, given the irrational and circular reasoning of both the courts and the public. Miller would later write: "The more I read into the Salem panic, the more it touched off corresponding images of common experiences in the fifties."

McCarthy himself came under increasing attack in the mid-fifties. On March 9, 1954, famed CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow aired a highly critical "Report on Joseph R. McCarthy" that used footage of McCarthy himself to portray him as dishonest in his speeches and abusive toward witnesses. In April of the same year the Army-McCarthy Hearings began and were televised live on the new American Broadcasting Company. This allowed the public and press to view first-hand McCarthy's interrogation of individuals and his controversial tactics. In one exchange, McCarthy reminded the Army's attorney general, Joseph Welch that he had an employee in his law firm who had belonged to an organization that had been accused of Communist sympathies. Welch famously rebuked McCarthy: "Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?" This exchange reflected a growing negative public opinion of McCarthy.

The decline of McCarthyism

As the nation moved into the mid and late fifties, the attitudes and institutions of McCarthyism slowly weakened. Changing public sentiments undoubtedly had a lot to do with this, but one way to chart the decline of McCarthyism is through a series of court decisions.

A key figure in the end of the blacklisting of McCarthyism was John Henry Faulk. Host of an afternoon comedy radio show, Faulk was a leftist active in his union, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. He was scrutinized by AWARE, one of the private firms that examined individuals for signs of communist "disloyalty". Marked by AWARE as unfit, he was fired by CBS Radio. Almost uniquely among the many victims of blacklisting, Faulk decided to sue AWARE in 1957 and finally won the case in 1962. With this court decision, the private blacklisters and those who used them were put on notice that blacklisting was liable. Although some informal blacklisting continued, the private "loyalty checking" agencies were soon a thing of the past. Even before the Faulk verdict, many in Hollywood had decided it was time to break the blacklist. In 1960, Dalton Trumbo, one of the best known members of the Hollywood Ten, was publicly credited with writing the films Exodus and Spartacus.

Much of the undoing of McCarthyism came at the hands of the Supreme Court. Two Eisenhower appointees to the court--Earl Warren (who was made Chief Justice) and William J. Brennan, Jr.--proved to be more liberal than Eisenhower had anticipated, and he would later refer to the appointment of Warren as his "biggest mistake."

In 1956, the Supreme Court heard the case of Slochower v. Board of Education. Slochower was a professor at Brooklyn College who had been fired by New York City for invoking the Fifth Amendment when McCarthy's committee questioned him about his past membership in the Communist Party. The court prohibited such actions, ruling "...we must condemn the practice of imputing a sinister meaning to the exercise of a person's constitutional right under the Fifth Amendment. The privilege against self-incrimination would be reduced to a hollow mockery if its exercise could be taken as equivalent either to a confession of guilt or a conclusive presumption of perjury."

Another key decision was in the 1957 case Yates v. United States, in which the convictions of fourteen Communists was reversed. In Justice Black's opinion, he wrote of the original "Smith Act" trials: "The testimony of witnesses is comparatively insignificant. Guilt or innocence may turn on what Marx or Engels or someone else wrote or advocated as much as a hundred years or more ago. When the propriety of obnoxious or unfamiliar view about government is in reality made the crucial issue, prejudice makes conviction inevitable except in the rarest circumstances."

Also in 1957, the Supreme Court ruled on the case of Watkins v. United States, curtailing the power of HUAC to punish uncooperative witnesses by finding them in contempt of Congress. Justice Warren wrote in the decision: "The mere summoning of a witness and compelling him to testify, against his will, about his beliefs, expressions or associations is a measure of governmental interference. And when those forced revelations concern matters that are unorthodox, unpopular, or even hateful to the general public, the reaction in the life of the witness may be disastrous."

In its 1958 decision on Kent v. Dulles, the Supreme Court halted the State Department from using the authority of its own regulations to refuse or revoke passports based on an applicant's communist beliefs or associations.

Continuing controversy

emo's are not only gay but retarded!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Though the interpretation of the Red Scare might seem to be of only historical interest following the end of the Cold War, the political divisions it created in the United States continue to manifest themselves, and the politics and history of anti-Communism in the United States are still contentious. One source of controversy is that repressive actions taken against the radical left during the McCarthy period are viewed as providing a historical template for similar actions against Muslims following the September 11th terrorist attacks. This analogy has been made explicit both by left-wing opponents of such actions (such as the American Civil Liberties Union) and right-wing proponents (such as Ann Coulter) alike. The guilt, innocence, and good or bad intentions of the icons of the Red Scare (McCarthy, the Rosenbergs, Alger Hiss, Whittaker Chambers, Elia Kazan) are still discussed as proxies for the imputed virtues or vices of their successors and sympathizers. See historical revisionism.

From the viewpoint of some conservatives and McCarthy supporters, past and present, the identification of foreign agents and the suppression of "radical organizations" was necessary. Anti-Communists of the period felt there was a dangerous subversive element that posed a danger to the security of the country, thereby justifying extreme measures.

Current use of the term

Since the time of McCarthy, the word "McCarthyism" has entered American speech as a general term for a variety of distasteful practices: aggressively questioning a person's patriotism, making poorly supported accusations, using accusations of disloyalty to pressure a person to adhere to conformist politics or to discredit an opponent, subverting civil rights in the name of national security and the use of demagoguery are all often referred to as McCarthyism.

Notes

- For example, Yates v. United States, 1957; or Watkins v. United States, 1957:

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pp 205, 207. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) -

For example, the California "Levering Oath" law, declared unconstitutional in 1967:

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 124. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

For example, Slochower v. Board of Education, 1956:

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 203. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

For example, Faulk vs. AWARE Inc., et al, 1956:

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 197. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Johnpoll, Bernard K (1994). A Documentary History of the Communist Party of the United States Vol. 3. Greenwood Press. pp. pg. xv. ISBN 0-313-28506-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg 41. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Brinkley, Alan (1995). The End Of Reform: New Deal Liberalism in Recession and War. Vintage. pp. pg. 141. ISBN 0-679-75314-1.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pp 6, 15, 78–80. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown. pp. pg. xiii. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Schrecker, Ellen (2004). The Age Of McCarthyism: A Brief History With Documents. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. pp 63-64. ISBN 0312294255.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) -

Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown. pp. pg. 4. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

D'Emilio, John (1998). Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities. University of Chicago Press; 2nd Edition. ISBN 0226142671.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown. pp. pg. 267. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Blacklisted in Hollywood; Dave Wagner & Paul Buhle (2003). Blacklisted: The Film Lover's Guide to the Hollywood Blacklist. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6145-X.

- Blacklisted in his profession, committed suicide in 1959; Bosworth, Patricia (1998). Anything Your Little Heart Desires: An American Family Story. Touchstone. ISBN 0684838486.

- Indicted under the Foreign Agents Registration Act; Dubois, W. E. B. (1968). The Autobiography of W. E. B. Dubois. International Publishers. ISBN 0717802345.

-

Blacklisted, imprisoned for contempt of Congress; Sabin, Arthur J. (1999). In Calmer Times: The Supreme Court and Red Monday. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. pg. 75. ISBN 0-8122-3507-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

On the Red Channels blacklist for artists and entertainers; Schrecker, Ellen (2002). The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. pg. 244. ISBN 0-312-29425-5.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Blacklisted in Hollywood; Schrecker, Ellen (2002). The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. pg. 244. ISBN 0-312-29425-5.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) -

Blacklisted and unemployed, committed suicide in 1955;

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg 156. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Security clearance withdrawn; Schrecker, Ellen (2002). The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. pg. 41. ISBN 0-312-29425-5.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) -

Blacklisted, passport revoked; Manning Marable, John McMillian, Nishani Frazier, editors (2003). Freedom on My Mind: The Columbia Documentary History of the African American Experience. Columbia University Press. pp. pg. 559. ISBN 0-231-10890-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

Subpoenaed by New Hampshire Attorney General, indicted for contempt of court;

Heale, M. J. (1998). McCarthy's Americans: Red Scare Politics in State and Nation, 1935-1965. University of Georgia Press. pp. pg. 73. ISBN 0-8203-2026-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Passport revoked, incarcerated; Chang, Iris (1996). Thread of the Silkworm. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00678-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Truman, Harry S. (1950). "Veto of the Internal Security Bill". Truman Presidential Museum & Library. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) -

"Margaret Chase Smith Library; "Declaration of Conscience"". Retrieved 2006-08-04.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) -

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 29. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 114. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Miller, Arthur (1996-10-21). "Why I Wrote "The Crucible"". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Faulk, John Henry (1963). Fear on Trial. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-72442-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 197. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Sabin, Arthur J. (1999). In Calmer Times: The Supreme Court and Red Monday. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. pg. 5. ISBN 0-8122-3507-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 203. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) -

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 205. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) -

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 207. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) -

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 211. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

See also

- Joseph McCarthy

- Anti-Communism

- Industrial Workers of the World

- Communist Party USA

- House Committee on Un-American Activities

- War on Terrorism

- Milo Radulovich

- Inquisition

- Witch-hunt

- Good Night, and Good Luck., a 2005 film about Edward Murrow and the McCarthy episode

Further reading

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Basic Books, 1999, hardcover edition, ISBN 0-465-00310-9

- John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, In Denial : Historians, Communism, and Espionage, Encounter Books, September, 2003, hardcover, 312 pages, ISBN 1-893554-72-4

- Victor Navasky Cold War Ghosts, 2001, The Nation

- Powers, Richard Gid (1997). Not Without Honor: A History of American AntiCommunism. Free Press.

- Price, David H. Threatening Anthropology: McCarthyism and the FBI's Surveillance of Activist Anthropologists Duke University Press, 2004.

External links

- International Journal of Baudrillard Studies

- What McCarthyism Means Today

- Two Cheers for "McCarthyism"?