This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Karakaj007 (talk | contribs) at 14:57, 9 December 2017 (I added a simple description of the lands King Caslav controlled.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:57, 9 December 2017 by Karakaj007 (talk | contribs) (I added a simple description of the lands King Caslav controlled.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Archon (ἄρχων)

| Časlav | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| archon (ἄρχων) | |||||

Illustration Illustration | |||||

| Prince of Serbia | |||||

| Reign | c. 927 – c. 960 | ||||

| Predecessor | Zaharija | ||||

| Successor | possibly Tihomir | ||||

| Born | before 896 Preslav, Bulgaria | ||||

| Died | c. 960 Sava banks | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Vlastimirović dynasty | ||||

| Father | Klonimir | ||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||

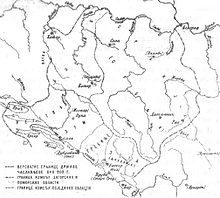

Časlav (Template:Lang-gr, Serbian Cyrillic: Часлав ; c. 890s – 960) was Prince of the Serbs from c. 927 until his death in c. 960. He significantly expanded the Serbian Principality when he managed to unite several Slavic tribes, stretching his realm over the shores of the Adriatic Sea, the Sava river and the Morava valley. He successfully fought off the Magyars, who had crossed the Carpathians and ravaged Central Europe, when they invaded Bosnia. Časlav is remembered, alongside his predecessor Vlastimir, as founders of Serbia in the Middle Ages.

Časlav was the son of Klonimir, a son of Strojimir who ruled as co-prince in 851–880. He belongs to the first Serbian dynasty, the Vlastimirovićs (ruling since the early 7th century), and is the last known ruler of the family.

Background

After the death of Prince Vlastimir, Serbia was ruled as an oligarchy by his three sons: Mutimir, Gojnik and Strojimir, although Mutimir, the eldest, had supreme rule.

In the 880s, Mutimir seized the throne, exiling his brothers and Klonimir, who was Strojimir's son, to the Bulgar Khanate; the court of Boris I of Bulgaria. This was most likely due to treachery. Petar, the son of Gojnik, was kept at the Serbian court of Mutimir for political reasons, but he soon fled to Croatia.

When Mutimir died, his son Pribislav inherited the rule, but he only ruled for a year; Petar returned and defeated him in battle and seized the throne; Pribislav fled to Croatia with his brothers Bran and Stefan. Bran was defeated, captured and blinded (blinding was a Byzantine tradition that meant to disqualify a person to take the throne). In 896, Klonimir returned from Bulgaria, backed by Boris I, taking the important stronghold Destinikon. Klonimir was defeated and killed.

The Byzantine–Bulgarian Wars made de facto the First Bulgarian Empire the most powerful Empire of Southeastern Europe. The Bulgarians won after invading at the right time, they met little resistance in the north because of the Byzantines fighting the Arabs in Anatolia.

Early life

Časlav was born in the 890s (before 896) in Preslav, the capital of the First Bulgarian Empire, growing up at the court of Simeon I. His father was Klonimir.

In 924, Časlav was sent to Serbia with a large Bulgarian army. The army ravaged a good part of Serbia, forcing Zaharija to flee to Croatia. Symeon summoned all the Serbian dukes to pay homage to their new Prince, but instead of instating Časlav, he took them all captive, annexing Serbia. Bulgaria now considerably expanded its borders; neighbouring ally Michael of Zahumlje and Croatia, where Zaharija was exiled and soon died. Croatia at this time was ruled by the most powerful monarch in Croatian history, Tomislav.

Reign

| Vlastimirović dynasty |

|---|

Bulgarian rule was not popular, many Serbs fled to Croatia and Byzantium. After the death of Simeon (927) Časlav and four friends escaped to Serbia. Časlav found popular support and restored the state, many exiles quickly returned. He immediately submitted to Byzantine overlordship of Romanos I Lekapenos and gained financial and diplomatic support for his efforts. He maintained close ties with Byzantium throughout his whole reign. Byzantine influence (Byzantine church in particular) greatly increased in Serbia, Orthodox influences from Bulgaria as well. The period was crucial to the future Christian demonym (Orthodox versus Catholic), as ties formed in this era were to have great importance on how the different Slavic churches would line up when they would split (Great Schism, 1054). Many scholars have felt that the Serbs, being in the middle of the Roman and Orthodox jurisdiction, could have been either way, unfortunately information on this era and region is scarce.

He enlarged Serbia, uniting the tribes of Bosnia, Herzegovina, Old Serbia and Montenegro (incorporated Zeta, Pagania, Zahumlje, Travunia, Konavle, Bosnia and Rascia into Serbia, "ι Σερβλια"). He took over regions previously held by Michael of Zahumlje, who disappeared from sources in 925.

Principality borders

Constantine Phorphirogenitus writes that Časlav "united all Serbian lands". Although this is a bit inprecise directive for exact border of Caslav's stae, it's simply neccesary to determine the borders of Serbian ethnic space and the lands which are considered "Serbian" in this period in order to determine the borders of Caslav's principality.

Phorphirogenitus and Einhard in his Royal Frankish Annals (Annales Regni Francorum) say that Serbs inhabit Roman Dalmatia, whose western border Tacitus positions somewhere on the "eastern hilltops", so that it includes regions of Lika, Krbava and Gacko. Phorphirogenitus also states:

"Their land was divided into 11 provinces and thay are: Hlebiana, Tzenzena, Emota, Pleba, Pesenta, Parathalassia, Brebere, Nona, Tnena, Sidraga, Nina, and their ban(boanos) has (in his jurisdiction) Kribasan, Litzan, Goutzeska" So, Kribasan (Krbava), Litzan (Lika) and Goutzeska do not belong within 11 Croatian provinces, the Croatian ban only has jurisdiction over them, which directly implies that Croats do not live in them. This proves that the border of Serbian ethnic space was on the border of Lika and Liburnia, which was, the probable border of Caslav's Serbia.

Slavonian Kniaz (Prince) Ljudevit Posavski, according to Frankish Annals, "had fled to the Serbs, who control a large portion of the province of Dalmatia", and there he was killed by Borna's uncle (Borna's mother therefore a Serb woman).

War with Magyars and death

Main article: Magyar-Serb conflict

The Magyars had settled in the Carpathian basin in 895. In the Byzantine-Bulgarian Wars, Emperor Leo had employed the Magyars against the Bulgars in 894. In the years following, the Magyars mainly concentrated on the lands to the west of their realm. In 934 and 943 the Magyars raided far into the Balkans, deep into Byzantine Thrace.

According to CPD, the Magyars led by Kisa invaded Bosnia, and Časlav hurried and encountered them at the banks of river Drina. The Magyars were decisively defeated, with Kisa being slewn by voivode Tihomir. Časlav married off his daughter to Tihomir, as a result of his courage and slaying of the Magyar leader. Kisa's widow requested from the Magyar leaders to give her an army for vengeance. With an "unknown number" of troops, the widow returned and surprised Časlav at Syrmia. In the night, the Magyars attacked the Serbs, captured Časlav and all of his male relatives. On the command of the widow, all of them were bound by their hands and feet and thrown into the Sava river. The events are dated to around 960 or shortly thereafter, as De Administrando Imperio does not mention this event.

Aftermath

After Časlav's death the realm crumbled, local nobles restored the control of each province, and according to the 'CPD', his son-in-law Tihomir ruled Rascia. The written information about the first dynasty ends with the death of Časlav.

The Catepanate of Ras is established between 971–976, during the rule of John Tzimiskes (r. 969–976). A seal of a strategos of Ras has been dated to Tzimiskes' reign, making it possible for Tzimiskes' predecessor Nikephoros II Phokas to have enjoyed recognition in Rascia. The protospatharios and katepano of Ras was a Byzantine governor named John. Data on the katepano of Ras during Tzimiskes' reign is missing. Byzantine military presence ended soon thereafter with the wars with Bulgaria, and was re-established only c. 1018 with the short-lived Theme of Sirmium, which however did not extend much into Rascia proper. Bosnia emerges as a state after the death of Časlav.

In the 990s, Jovan Vladimir emerges at the most powerful Serbian noble. With his court centered in Bar on the Adriatic coast, he had much of the Serbian Pomorje ('maritime') under his control including Travunia and Zachlumia. His realm may have stretched west- and northwards to include some parts of the Zagorje ('hinterlands', inland Serbia and Bosnia) as well. Cedrenus calls his realm "Trymalia or Serbia", according to Radojicic and Ostrogorski, the Byzantines calls Zeta – Serbia, and its inhabitants Serbs. Vladimir’s pre-eminent position over other Slavic nobles in the area explains why Emperor Basil II approached him for an anti-Bulgarian alliance. With his hands tied by war in Anatolia, Emperor Basil required allies for his war against Tsar Samuel, who had much of Macedonia. In retaliation, Samuel invaded Duklja in 997, and pushed through Dalmatia up to the city of Zadar, incorporating Bosnia and Serbia into his realm. After defeating Vladimir, Samuel reinstated him as a vassal Prince.

Legacy

Stevan Sremac (1855–1906) authored Veliki župan Časlav in 1903.

Family

According to the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, Časlav had one daughter:

See also

- List of Serbian monarchs

- Serbia in the Middle Ages

- Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja

- Battle of Drina (medieval)

| ||||||||||

Annotations

- Name: The first attestation of his name is the Greek Tzeésthlabos (Τζεέσθλαβος), in Latin Caslavus, in Serbian Časlav. He was a descendant of Vlastimirović, his father was Klonimir, hence, according to the contemporary naming culture, his name was Časlav Klonimirović Vlastimirović.

- Reign : Ćorović dates his accession to 927 or shortly thereafter, Ostrogorsky to 927 or 928, supported by Fine. Ćorović dates his death to around 960, as does Fine.

- Tihomir: The only mention of Tihomir is taken from the Chronicle of the Priest of Doclea. Various inaccurate and wrong claims make it an unreliable source, the majority of modern historians conclude that it is mainly fictional, or wishful thinking, pointing at the religious tone of the region and "author" itself. One of the main controversies lies in the fact that the "Antivari Archepiscopate" did not exist between 1142 and 1198 – at which time , Grgur, the author, was Archbishop. The work enumerates the Serbian rulers mentioned in De Administrando Imperio, but contradict the forming and divisions of the South Slavs. It nevertheless gives a unique sight into South Slavic history. The oldest copies of the manuscript date to the 17th century, thereof claims of dubious status.

References

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 141.

- ^ Đekić 2009.

- Longworth, Philip (1997), The making of Eastern Europe: from prehistory to postcommunism (1997 ed.), Palgrave Macmillan, p. 321, ISBN 0-312-17445-4

- Fine 1991, p. 154.

- Theophanes Continuatus, p. 312., cited in Vasil'ev, A. (1902) (in Russian). Vizantija i araby, II. pp. 88, p. 104, pp. 108–111

- ^ The entry of the Slavs into Christendom, p. 209

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 153.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 159.

- ^ Srbi između Vizantije, Hrvatske i Bugarske;

- Fine 1991, p. 160.

- ^ Einchard, "Carolingian chronicles: Royal Frankish annals and Nithard's Histories." trans.Scholz, Rogers, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press

- De Administrando Imperio by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, edited by Gy. Moravcsik and translated by R. J. H. Jenkins, Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Washington D. C., 1993

- ^ Др. Борислав Влајић (1999) "Срби староседеоци Балкана и Паноније", "Стручна Књига", Београд

- ^ Stephenson, p. 39

- ^ Živković, Portreti srpskih vladara, p. 57

- GK, Abstract: "the establishment of catepanate in Ras between 971 and 976"

- ^ Stephenson, Paul. The Legend of Basil the Bulgar-slayer. p. 42.

- Paul Magdalino, Byzantium in the year 1000, p. 122

- Academia, 2007, Byzantinoslavica, Volumes 65–66, p. 132

- Bojana Krsmanović, Ljubomir Maksimović, Taxiarchis G. Kolias (2008), The Byzantine province in change: on the threshold between the 10th and the 11th century, p. 189, Institute for Byzantine Studies, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts,

- Ćirković 2004, p. 40–41.

- Cedrenus II, col. 195.

- Nikola Banasevic, Letopis popa Dukqanina i narodna predawa, p. 79, Document

- Stevan Sremac (1903). Veliki župan Časlav. Izd. Matice srpske.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1993). De Administrando Imperio (Moravcsik, Gyula ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.

- Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1830). De Ceremoniis (Reisky, J. ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.

- Einhard. Annales regni Francorum [Royal Frankish Annals] (in Latin).

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Secondary sources

- Bury, J. B. (2008). History of the Eastern Empire from the Fall of Irene to the Accession of Basil: A.D. 802-867. ISBN 1-60520-421-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ćorović, Vladimir (2001). Istorija srpskog naroda (Internet ed.). Belgrade: Ars Libri.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Đekić, Đ (2009). "Why did prince Mutimir keep Petar Gojnikovic?" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help) - Ferjančić, Božidar (1997). "Basile I et la restauration du pouvoir byzantin au IXème siècle" [Vasilije I i obnova vizantijske vlasti u IX veku]. Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta (in French) (36). Belgrade: 9–30.

- Ferjančić, Božidar (2007). Vizantijski izvori za istoriju naroda Jugoslavije II (fototipsko izdanje originala iz 1959 ed.). Belgrade. pp. 46–65. ISBN 978-86-83883-08-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mijatovic, Cedomilj (2007) . Servia and the Servians. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 1-60520-005-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Runciman, Steven (1930). A history of the First Bulgarian Empire. London: G. Bell & Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77017-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Живковић, Тибор (2002). Јужни Словени под византијском влашћу 600-1025 (South Slavs under the Byzantine Rule 600-1025). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ, Службени гласник.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Živković, Tibor (2006). Portreti srpskih vladara (IX—XII vek). Belgrade. ISBN 86-17-13754-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550-1150. Belgrade: The Institute of History, Čigoja štampa.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)