This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Crouchs (talk | contribs) at 21:48, 22 March 2018 (→Lead and line: Fixed typo). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:48, 22 March 2018 by Crouchs (talk | contribs) (→Lead and line: Fixed typo)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Depth sounding refers to the act of measuring depth. It is often referred to simply as sounding. Data taken from soundings are used in bathymetry to make maps of the floor of a body of water, and were traditionally shown on nautical charts in fathoms and feet. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the agency responsible for bathymetric data in the United States, still uses fathoms and feet on nautical charts. In other countries, the International System of Units (metres) has become the standard for measuring depth.

Terminology

"Sounding" derives from the Old English sund, meaning swimming, water, sea; it is not related to the word sound in the sense of noise or tones, but to sound, a geographical term.

Traditional terms for soundings are a source for common expressions in the English language, notably "deep six" (a sounding of 6 fathoms): see John Ehrlichman. On the Mississippi River in the 1850s, the leadsmen also used old-fashioned words for some of the numbers; for example instead of "two" they would say "twain". Thus when the depth was two fathoms, they would call "by the mark twain!". The American writer Mark Twain, a former river pilot, likely took his pen name from this cry. The term lives on in today's world in echo sounding, the technique of using sonar to measure depth.

History

Lead and line

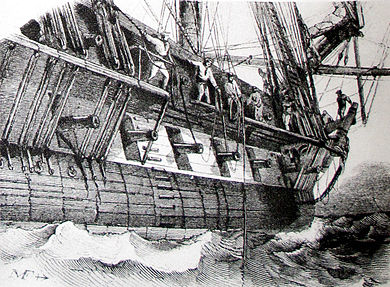

A sounding line or lead line is a length of thin rope with a plummet, generally of lead, at its end. Regardless of the actual composition of the plummet, it is still called a "lead." Leads were swung, or cast, by a leadsman, usually standing in the chains of a ship, up against the shrouds.

Measuring the depth of water by lead and line dates back to ancient civilization. Greek and Roman navigators are known to have used sounding leads, some of which have been uncovered by archaeologists. Sounding by lead and line continued throughout the medieval and early modern periods. The Bible describes lead and line sounding in Acts, whilst the Bayeux Tapestry documents the use of a sounding lead during King Harold’s landing in Normandy. Throughout this period, lead and line sounding operated alongside sounding poles, particularly when navigating in shallower waters and on rivers.

At sea, in order to avoid repeatedly hauling in and measuring the wet line by stretching it out with one's arms, it became traditional to tie marks at intervals along the line. These marks were made of leather, calico, serge and other materials, and so shaped and attached that it was possible to "read" them by eye during the day or by feel at night. The marks were at every second or third fathom, in a traditional order: at 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 13, 15, 17, and 20 fathoms. The "leadsman" called out the depth as he read it off the line. If the depth was at a mark he would call "by the mark" followed by the number, while if it was between two marks, he would call "by the deep" followed by the estimated number; thus "by the mark five," since there is a five-fathom mark, but "by the deep six," since there is no six-fathom mark. Fractions would be called out by preceding the number with the phrases "and a half," "and a quarter," or "a quarter less"; thus 4 3/4 fathoms would be called as "a quarter less five," 3 1/2 as "and a half three," and so on.

Soundings were also taken to establish the ship's position as an aid in navigation, not merely for safety. Soundings of this type were usually taken using leads that had a wad of tallow in a concavity at the bottom of the plummet. The tallow would bring up part of the bottom sediment (sand, pebbles, clay, shells) and allow the ship's officers to better estimate their position by providing information useful for pilotage and anchoring. If the plummet came up clean, it meant the bottom was rock. Nautical charts provide information about the seabed materials at particular locations.

Mechanisation

During the nineteenth century, a number of attempts were made to mechanise depth sounding. Designs ranged from complex brass machines to relatively simple pulley systems. Navies around the world, particularly the Royal Navy in Britain, were concerned about the reliability of lead and line sounding. The introduction of new machines was understood as a way to introduce standardised practices for sounding in a period in which naval discipline was of great concern.

One of the most widely adopted sounding machines was developed in 1802 by Edward Massey, a clockmaker from Staffordshire. The machine was designed to be fixed to a sounding lead and line. It featured a rotor which turned a dial as the lead sank to the sea floor. On striking the sea floor, the rotor would lock. Massey’s sounding machine could then be hauled in and the depth could be read off the dials in fathoms. By 1811, the Royal Navy had purchased 1,750 of these devices: one for every ship in commission during the Napoleonic Wars. The Board of Longitude was instrumental in convincing the Royal Navy to adopt Massey's machine.

Massey’s was not the only sounding machine adopted during the nineteenth century. The Royal Navy also purchased a number of Peter Burt’s buoy and nipper device. This machine was quite different from Massey’s. It consisted of an inflatable canvas bag (the buoy) and a spring-loaded wooden pulley block (the nipper). Again, the device was designed to operate alongside a lead and line. In this case, the buoy would be pulled behind the ship and the line threaded through the pulley. The lead could then be released. The buoy ensured that the lead fell perpendicular to the sea floor even when the ship was moving. The spring-loaded pulley would then catch the rope when the lead hit the sea bed, ensuring an accurate reading of the depth.

Both Massey and Burt’s machines were designed to operate in relatively shallow waters (up to 150 fathoms). With the growth of seabed telegraphy in the later nineteenth century, new machines were introduced to measure much greater depths of water. The most widely adopted deep-sea sounding machine in the nineteenth century was Kelvin’s sounding machine, designed by William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and patented in 1876. This operated on the same principle as lead and line sounding. In this case, the line consisted of a drum of piano wire whilst the lead was of a much greater weight. Later versions of Kelvin’s machine also featured a motorised drum in order to facilitate the winding and unwinding of the line. These devices also featured a dial which recorded the length of line let out.

Echo sounding

Both lead-and-line technology and sounding machines were used during the twentieth century, but by the twenty-first, echo sounding had increasingly displaced both of those methods.

The first practical fathometer (literally "fathom measurer"), which determined water depth by measuring the time required for an echo to return from a high-pitched sound sent through the water and reflected from the sea floor, was invented by Herbert Grove Dorsey and patented in 1928.

See also

References

- "Sounding Pole to Sea Beam". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- "Sound, v". Oxford English Dictionary (Second ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 1969.

- ^ Hohlfelder, R., ed. (2008). "Testing the Waters: The Role of Sounding-Weights in Ancient Mediterranean Navigation". The Maritime World of Ancient Rome. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 119–176.

- Kemp, P., ed. (1976). The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. London: Oxford University Press. p. 150.

- ^ Hutton, Charles (1795). A Mathematical and Philosophical Dictionary: Containing an Explanation of the Terms, and an Account of the Several Subjects Comprized under the Heads Mathematics, Astronomy, and Philosophy both Natural and Experimental (Volume 2). pp. 474–475.

- ^ Poskett, J (2015). "Sounding in silence: men, machines and the changing environment of naval discipline, 1796-1815 (free PDF available online)". The British Journal for the History of Science. 48 (2). Cambridge University Press: 213–232. doi:10.1017/S0007087414000934. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- McConnell, A (1982). No Sea Too Deep: The History of Oceanographic Instruments. Bristol: Hilger. p. 28.

- Dunn, R (2012). "'Their brains over-taxed': Ships, Instruments and Users". In Dunn, R; Leggett, D (eds.). Re-inventing the Ship: Science, Technology and the Maritime World, 1800-1918. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 131–156.

- "Echo Sounding / Early Sound Methods". National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). NOAA Central Library. 2006.

In answer to the need for a more accurate depth registering device, Dr. Herbert Grove Dorsey, who later joined the C&GS, devised a visual indicating device for measuring relatively short time intervals and by which shoal and deep depths could be registered. In 1925, the C&GS obtained the very first Fathometer, designed and built by the Submarine Signal Company.

External links

- The Lead Line -- Construction and use (retrieved Sept 2006).