This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 58.168.175.58 (talk) at 07:03, 24 October 2006. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:03, 24 October 2006 by 58.168.175.58 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Vietnam War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||||

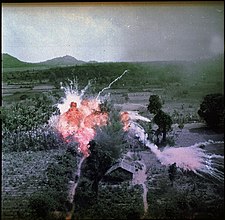

| File:Burning Viet Cong base camp.jpg Vietnamese village after an attack. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

US 1,000,000 South Korea 300,000 Australia 48,000 New Zealand 3,900 |

North Vietnam and Viet Cong ~2,000,000 PRC 320,000 Soviet Union 6,000 North Korea unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

South Vietnamese dead: 230,000 South Vietnamese wounded: 300,000 US dead: 58,209 US wounded: 153,303 South Korean dead: 5,000 South Korean wounded: 11,000 Australian dead: 520 Australian wounded: 3,131 New Zealand dead: 38 New Zealand wounded: 187 Philippines dead: 99 Thailand dead: 351 |

North Vietnamese and NLF dead: 1,100,000 North Vietnamese and NLF wounded: 600,000 Chinese dead: 1,100 Chinese wounded: 4,200 Soviet Union 16 killed North Korea 36+ killed | ||||||||

| Civilian dead (total Vietnamese): 2-4,000,000 | |||||||||

The Vietnam War was a conflict in which communist forces from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV or North Vietnam) and the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam, also known as the Việt Cộng (or VC) fought against anti-communist forces from the Republic of Vietnam (RVN or South Vietnam) and its allies — most notably the United States — in an effort to unify Vietnam into a single independent state.

It is also known as Vietnam Conflict, the Second Indochina War and in the US colloquially as Vietnam, The ’Nam or simply ’Nam. Vietnamese Communists have often referred to it as the American War or Kháng chiến chống Mỹ, the Resistance War Against America.

The war followed the failure of Vietnamese nationalists, in the form of the Viet Minh, to achieve control of southern Vietnam in their fight for independence from France, in the First Indochina War of 1946-54.

Allies of the Vietnamese communists included the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. South Vietnam's main anti-communist allies were the United States, South Korea, Australia, Thailand, the Philippines, and New Zealand. The United States, in particular, deployed large numbers of personnel to South Vietnam. US military advisors were involved in Vietnam from 1950, when they began to assist French colonial forces. In 1956, U.S. advisors assumed full responsibility for training the South Vietnamese army. Large numbers of American combat troops began to arrive in 1965. They left the country in 1973.

At various stages the conflict involved fighting around bases in the countryside, clashes between troops patrolling the rainforest, and guerrilla attacks on South Vietnamese towns. U.S. aircraft also conducted substantial aerial bombing campaigns, targeting both Viet Cong camps in the rainforest and the cities of North Vietnam. Large quantities of defoliating chemicals were also dropped from the air in an effort to reduce the cover available to Viet Cong troops.

Many Westerners consider the Vietnam War a "proxy war," one of several that occurred during the Cold War between the United States and its Western allies on the one hand, and the Soviet Union and/or the People's Republic of China on the other. The Korean War is another such war. Proxy wars occurred because the major players — especially the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. — were unwilling to fight each other directly because of the unacceptable costs of global nuclear war.

The Vietnam War finally ended on April 30, 1975, with the surrender of South Vietnam. The war had claimed millions of Vietnamese lives, a large number of them civilians. The casualties suffered by the US and other allies of South Vietnam were also deeply significant, a cause of great pain and suffering in those nations.

Background

- See also: History of Vietnam and First Indochina War

From 110 BC to the year 938 AD, except for brief periods, much of present-day Vietnam, especially the northern half, was part of China. After gaining independence from China, Vietnam went through a long history of resisting outside aggression. France had gained control of Indochina in a series of colonial wars beginning in the 1840s and lasting into the 1880s. At the Treaty of Versailles negotiations following the armistice that ended World War I in 1919, Hồ Chí Minh requested participation in order to obtain the independence of the Indochinese colonies. His request was rejected, and Indochina's status as a colony of France remained unchanged. During World War II, Vichy France cooperated with the occupying Imperial Japanese forces. Vietnam was under effective Imperial Japanese control, as well as de facto Japanese administrative control -- although the Vichy French continued to serve as the official administrators until 1944. Hồ came back to the country and formed a resistance group in the north. He was aided by American OSS agents, (precursors of today's CIA) some of whom had worked behind enemy lines in Indochina giving support to indigenous resistance groups, including on-site training by an OSS unit code-named "Deer Team." In 1944, the Japanese overthrew the French administration and humiliated its colonial officials in front of the Vietnamese population. The Japanese then began to encourage nationalist activity among the Vietnamese. Late in the war, Japan granted Vietnam nominal independence.

After the war was over and following the Japanese surrender, the Vietnamese nationalists, communists, and other groups hoped to finally take control of the country. The Japanese army in Indochina assisted the Viet Minh -- Hồ's resistance army -- and other Vietnamese independence groups by imprisoning French officials and soldiers and handing over public buildings to the Vietnamese. On September 2, 1945, Hồ Chí Minh spoke at a ceremony at Hanoi in which he proclaimed the formation of a new Vietnamese republican government under his leadership. In his speech he cited the U.S. Declaration of Independence and a band played "The Star Spangled Banner." He also issued a Declaration of Independence, listing their complaints against French rule. Hồ, who had been a member of the Third Communist International since the early 1920s, hoped that the Americans would ally themselves with a Vietnamese nationalist movement, communist or otherwise. He based this hope on speeches by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt against the continuation of European colonialism after World War II. Roosevelt, however, had moderated his position after the British -- who wanted to keep their own colonies -- objected.

The government only lasted a few days, however, as at the Potsdam Conference it had been decided that Vietnam would be occupied by Chinese and British troops who would supervise the Japanese surrender and repatriation. The Chinese army arrived in the north a few days after Hồ Chí Minh's ceremony in September 1945, and took over areas north of the 16th parallel. The British arrived in the south in October and supervised the surrender and departure of the Japanese army from Indochina south of the 16th parallel. With this, the government of Hồ Chí Minh effectively ceased to exist. In the South, the French prevailed upon the British to turn control of the region back over to them. French officials, when released from Japanese prisons at the end of September 1945, also took matters into their own hands in some areas. In the north, France negotiated with both the nationalist government of China and the Viet Minh. By agreeing to give up Shanghai and its other concessions in China, the French persuaded the Chinese to allow them to return to northern Vietnam and negotiate with the Viet Minh. Hồ agreed to allow French forces to land outside Hanoi, while France agreed to recognize an independent Vietnam within the French Union. In the meantime, Hồ took advantage of the period of negotiation to liquidate competing nationalist groups in the north. After failed negotiations with Hồ Chí Minh over the possibility of his forming a government within the Union, the French entered Hanoi and Hồ's Việt Minh fled into the hills and began an insurgency, marking the beginning of the First Indochina War, during which France attempted to reestablish Vietnam as part of the French overseas domain. After 1949, and the communist victory in China, Mao Zedong was able to supply weapons to Hồ Chí Minh's forces. The Viet Minh gained the weapons and supplies necessary to transform themselves from an insurgency into a regular army.

Meanwhile, the United States was supplying the French with military aid. In 1950, the US Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) arrived to screen French requests for aid, advise on strategy and train Vietnamese soldiers. In 1956, MAAG assumed from the French full responsibility for training the Vietnamese army. By 1954, the United States had given 300,000 small arms and machine guns, and $1 billion to support the French war effortand was shouldering at least 80% of the cost.

The Viet Minh eventually handed the French a major military defeat at Ðiện Biên Phủ. At the 1954 Geneva Conference the French government negotiated a peace agreement with the Viet Minh which allowed the French to leave Indochina and all three nations of the colony (Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam) were granted independence. However, Vietnam was temporarily partitioned at the 17 parallel, above which the Viet Minh established a socialist state, (the Democratic Republic of Vietnam or DRV) and below which a non-communist state was established under the Emperor Bảo Đại (the State of Vietnam). Bao Dai's Prime Minister, Ngo Dinh Diem, shortly thereafter removed him from power, and established himself as President of the Republic of Vietnam.

As dictated by the Geneva Accords of 1954, the division of Vietnam was meant to be temporary, pending free elections for a national leadership. The agreement stipulated that the two military zones, which were separated by the temporary demarcation line, "should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary," and specifically stated that "general elections shall be held in July 1956." However, the Diem government refused to enter into negotiations to hold the stipulated election, encouraged by the United States' unwillingness to allow a communist victory in an all-Vietnam election. Questions were also raised about the legitimacy of any poll held in the communist-run North. The US-supported government of South Vietnam justfied its refusal to comply with the Geneva Accords by virtue of the fact it had not signed them. Beginning in the summer of 1955, Diem launched a 'Denounce the Communists' campaign, during which communists and other anti-government elements were arrested, imprisoned or executed. Also at this time, people moved across the partition line in both directions. It is estimated that around 130,000 Vietnamese moved from South Vietnam to North Vietnam, while more than a million Vietnamese moved from north to south.

From insurgency to Americanization

As opposition to Diem's rule in South Vietnam grew, a low-level insurgency began there in 1957, conducted mainly by Viet Minh cadres who remained in the South and had hidden caches of weapons in case unification failed to take place through elections. In late 1956 one of the leading Communists in the South, Lê Duẩn, returned to Hanoi to urge that the Vietnam Workers' Party (VWP) take a firmer stand on national reunification, but Hanoi hesitated from launching a full-scale military struggle. Finally, in January 1959, under pressure from southern cadres who were increasingly being successfully targeted by Diem's secret police, the Central Committee of the VWP issued a secret resolution authorizing the use of armed struggle in the South.

In December 1960, under instruction from Hanoi, southern communists established the National Liberation Front in order to overthrow the government of the South. The NLF was made up of two distinct groups: South Vietnamese intellectuals who opposed the South Vietnamese government and were nationalists, such as Truong Nhu Tang; and communists who had remained in the south after the partition and regroupment of 1954, such as Nguyen Thi Binh, as well as those communists who had come from the north. While there were many non-communist members of the NLF, they were subject to the control of the VWP cadres and increasingly side-lined as the conflict continued; they did, however, enable the NLF to portray itself as a primarily nationalist, rather than communist, movement.

The Diệm government was initially able to cope with the insurgency with the aid of U.S. advisers, and by 1962 seemed to be winning. Senior U.S. military leaders were receiving positive reports from the U.S. commander, Gen. Paul D. Harkins of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. U.S. President John F. Kennedy had increased the number of American "advisers" in the belief that he could duplicate the success of British counterinsurgency warfare in Malaya. The competing countries in the Cold War -- the United States on South Vietnam's side, the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China on North Vietnam's side -- became increasingly involved, and what had begun as a domestic insurgency began to become internationalized. In 1963, a communist offensive that began with the Battle of Ap Bac inflicted major losses on South Vietnamese army units. This was the first large-scale battle since Dien Bien Phu, a major departure from the assassinations and guerrilla activities that had preceded it.

Ap Bac was a sign that the insurgency was escalating as a result of the increasing supplies of men and weapons from the North. Diem was already deeply unpopular with many of his own people because of his administration's nepotism, corruption, and its apparent bias in favor of the Catholic minority -- of which Diem was a part -- at the expense of the Buddhist majority. Some policy-makers in Washington began to believe that Diem was incapable of defeating the communists, and even feared that he might make a deal with Ho Chi Minh. During the summer of 1963 administration officials began discussing the possibility of a change of leadership in South Vietnam. The State Department was generally in favor of encouraging a coup while the Pentagon and CIA were more skeptical about the destabilizing consequences of a coup and wanted to continue a policy of pressuring Diem to change his policies, including removing his younger brother Ngo Dinh Nhu from all positions of power. Nhu was in charge of South Vietnam's secret police and had a body of troops loyal to him personally. As Diem's most powerful advisor, Nhu (along with his wife) had become a hated figure in South Vietnam whose continued influence was unacceptable to all members of the Kennedy administration. Eventually the administration determined that Diem was unwilling to further modify his policies and the decision was made to remove US support from the regime. This decision was made jointly between the State Department, Pentagon, National Security Advisor, and CIA. President Kennedy authorized the decision, and it was known that the result of removing US support from the Diem regime would be a coup d'etat.

In November, 1963, the U.S. embassy in Saigon indicated to coup plotters that they would not oppose the removal of Diem from power. The South Vietnamese President was overthrown by a military coup and was later executed along with Nhu. Another brother was subsequently assassinated by the new government. After the coup President Kennedy appeared to be genuinely shocked and dismayed by the assassinations, however top CIA officials were surprised that Kennedy didn't appear to have understood that this was a possible outcome. Chaos ensued in the security and defense systems of South Vietnam, while Hanoi took advantage of the situation to increase its support for the insurgents in the South. South Vietnam then entered a period of extreme political instability with a succession of different military rulers; the United States' involvement in South Vietnam dramatically increased; and the 'Americanization' of the war began.

The South Vietnamese government and its Western allies portrayed the conflict as an action against the use of armed violence as a means of political change, a principled opposition to communism —to deter the expansion of Soviet-based control throughout Southeast Asia, and to set the tone for any likely future superpower conflicts. The North Vietnamese government and its subordinate organization (NLF) viewed the war as a struggle to unite the country under a socialist government and to repel a foreign aggressor —a virtual continuation of the earlier war for independence against the French.

The Ho Chi Minh trail

- See also: Ho Chi Minh trail

North Vietnam received shipments of Russian and Chinese supplies at Haiphong harbor. This material was then transported down the Truong Son Trail (known to the rest of the world as the Ho Chi Minh Trail) into the hands of the NLF and Việt Cộng in South Vietnam. Complicating matters, the Truong Son Trail ran for most of its length through neighboring Laos and Cambodia, ending about thirty miles from Saigon. It was impossible to block the shipments of supplies from the north without bombing or invading those neighboring countries. But this bombing did not take place until late in the war. Laos and Cambodia, in the meantime, had their own Communist insurgencies, with the Pathet Lao insurgent group in Laos organized by North Vietnam. Later on, the North Vietnamese would invade and occupy parts of Laos. In 1965, Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia made a deal with China and North Vietnam that allowed North Vietnamese forces to establish permanent bases in the country and to use the port of Sihanoukville for delivery of military supplies. The Prince was later deposed and the supply route closed by Cambodian Premier, Lon Nol, in 1970. In the meantime, the Hồ Chí Minh Trail had steadily expanded to become the vital lifeline for communist forces in South Vietnam, including troops from the army of North Vietnam (the Vietnam People's Army, commonly abbreviated as PAVN), and as a result it later became a target of U.S. air operations.

United States involvement

Harry S. Truman and Vietnam (1945-1953)

Milestones of U.S. involvement under Harry S. Truman

- March 9, 1945 — Japan overthrows nominal French authority in Indochina and declares an independent Vietnamese puppet state. The French administration is disarmed.

- August 15, 1945 — Japan surrenders to the Allies. In Indochina, the Japanese administration allows Hồ Chí Minh to take over control of the country. This is called the August Revolution. Hồ Chí Minh borrows a phrase from the U.S. Declaration of Independence for his own declaration. Hồ Chí Minh fights with a variety of other political factions for control of the major cities.

- August 1945 — A few days after the Vietnamese "revolution", Chinese forces enter from the north and, as previously planned by the allies, establish an administration in the country as far south as the 16th parallel.

- September 26, 1945: OSS officer Lt. Col. A. Peter Dewey — working with the Viet Minh to repatriate Americans captured by the Japanese — is shot and killed by the Viet Minh, becoming the first American casualty in Vietnam.

- October 1945 — British troops land in southern Vietnam and establish a provisional administration. The British free French soldiers and officials imprisoned by the Japanese. The French begin taking control of cities within the British zone of occupation.

- February 1946 — The French sign an agreement with China. France gives up its concessions in Shanghai and other Chinese ports. In exchange, China agrees to assist the French in returning to Vietnam north of the 16th parallel.

- March 6, 1946 — After negotiations with the Chinese and the Viet Minh, the French sign an agreement recognizing Vietnam within the French Union. Shortly after, the French land at Haiphong and occupy the rest of northern Vietnam. The Viet Minh use the negotiating process with France and China to buy time to use their armed forces to destroy all competing nationalist groups in the north.

- December 1946 — Negotiations between the Viet Minh and the French break down. The Viet Minh are driven out of Hanoi into the countryside.

- 1947–1949 — The Viet Minh fight a limited insurgency in remote rural areas of northern Vietnam.

- 1949 — Chinese communists reach the northern border of Indochina. The Viet Minh drive the French from the border region and begin to receive large amounts of weapons from the Soviet Union and China. The weapons transform the Viet Minh from an irregular small-scale insurgency into a conventional army.

- May 1st 1950 — After the capture of Hainan Island from Chinese Nationalist forces by Chinese Communists, President Truman approves $10 million in military assistance for anti-communist efforts in Indochina.

- Following the outbreak of the Korean War, Truman announces "acceleration in the furnishing of military assistance to the forces of France and the Associated States in Indochina…" and sends 123 non-combat troops to help with supplies to fight against the communist Viet Minh.

- 1951 — Truman authorizes $150 million in French support.

Dwight D. Eisenhower and Vietnam (1953–1961)

Milestones of the escalation under Dwight D. Eisenhower.

- 1954 — The Viet Minh defeat the French at the battle of Dien Bien Phu. The defeat, along with the end of the Korean war the previous year, causes the French to seek a negotiated settlement to the war.

- 1954 — The Geneva Conference (1954), called to determine the post-French future of Indochina, proposes a temporary division of Vietnam, to be followed by nationwide elections to unify the country in 1956.

- 1954 — Two months after the Geneva conference, North Vietnam forms Group 100 with headquarters at Ban Namèo. Its purpose is to direct, organize, train and supply the Pathet Lao to gain control of Laos, which along with Cambodia and Vietnam formed French Indochina.

- 1955 — North Vietnam launches an 'anti-landlord' campaign, during which counter-revolutionaries are imprisoned or killed. The numbers killed or imprisoned are disputed, with historian Stanley Karnow estimating about 6,000 while others (see the book "Fire in the Lake") estimate only 800. R.J. Rummel puts the figure as high as 200,000.

- November 1, 1955 — Eisenhower deploys the Military Assistance Advisory Group to train the South Vietnam Army. This marks the official beginning of American involvement in the war as recognized by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

- April 1956 — The last French troops leave Vietnam.

- 1955–1956 — 900,000 Vietnamese flee the Viet Minh administration in North Vietnam and relocate in South Vietnam.

- 1956 — National unification elections do not occur.

- December 1958 — North Vietnam invades Laos and occupies parts of the country

- July 8, 1959 — Charles Ovnand and Dale R. Buis become the first two American Advisors to die in Vietnam.

- September 1959 — North Vietnam forms Group 959 which assumes command of the Pathet Lao forces in Laos

John F. Kennedy and Vietnam (1961–1963)

Timeline

- January 1961 — Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev pledges support for "wars of national liberation" throughout the world. The idea of creating a neutral Laos is suggested to Kennedy.

- May 1961 — Kennedy sends 400 American Green Beret "Special Advisors" to South Vietnam to train South Vietnamese soldiers following a visit to the country by Lyndon Johnson.

- June 1961 — Kennedy and Khrushchev meet at Vienna. Kennedy protests North Vietnam's attacks on Laos and points out that the U.S. was supporting the neutrality of Laos. Both leaders agree to pursue a policy of creating a neutral Laos.

- October 1961 — Following successful Viet Cong attacks, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara recommends sending six divisions (200,000 men) to Vietnam. Kennedy sends just 16,000 before the end of his Presidency in 1963.

- August 1, 1962 — Kennedy signs the Foreign Assistance Act of 1962 which provides "…military assistance to countries which are on the rim of the Communist world and under direct attack."

- January 3, 1963 — Viet Cong victory in the Battle of Ap Bac.

- May 1963 — Buddhists riot in South Vietnam after a conflict over the display of religious flags during the celebration of Buddha's birthday. Some Buddhists urge Kennedy to end U.S. support for Ngo Dinh Diem, who is Catholic. Photographs of protesting Buddhist monks burning themselves alive appear in U.S. newspapers.

- May 1963 — Republican Barry Goldwater declares that the U.S. should fight to win or withdraw from Vietnam. Later on, during his presidential campaign against Lyndon Johnson, his Democratic opponents accuse him of wanting to use atomic bombs in the conflict.

- November 1, 1963 — Military officers launch a coup d'état against Diem, with the tacit approval of the Kennedy administration. Diem leaves the presidential residence.

- November 2, 1963 — Diem is discovered and killed by rebel leaders, along with his brother Nhu.

- November 22,1963 — Kennedy is assassinated.

"Containment" of Communist expansion

The Kennedy administration remained essentially committed to the anti-Communist foreign policy inherited from the Truman and Eisenhower administrations. In 1961 Kennedy found himself faced with a three-part crisis that seemed similar to that faced by Truman in 1949–1950. 1961 had already seen the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and a negotiated settlement between the pro-Western government of Laos and the Pathet Lao communist movement. Fearing that another failure on the part of the United States to gain control and stop communist expansion would fatally damage U.S. credibility with its allies and his own reputation, Kennedy was determined to 'draw a line in the sand' and prevent a communist victory in Vietnam. "Now we have a problem in making our power credible", he said, "and Vietnam looks like the place."

The long-standing commitment of the United States to defend Vietnam was reaffirmed by President Kennedy on May 11 in National Security Action Memorandum #52 which became known as "The Presidential Program for Vietnam". Its opening statement reads:

- The U.S. objectives and concept of operations to prevent Communist domination of South Vietnam; to create in that country a viable and increasingly democratic society, and to initiate, on an accelerated basis, a series of mutually supporting actions of a military, political, economic psychological, and covert character designed to achieve this objective.

Kennedy was interested in using Special Forces for counterinsurgency warfare in Third World countries threatened by communist insurgencies. Originally intended for use behind front lines after a conventional invasion of Europe, Kennedy believed that the guerrilla tactics employed by special forces such as the Green Berets would be effective in the "brush fire" war in Vietnam. He saw British success in using such forces in Malaya as a strategic template. Thus in May 1961 Kennedy sent Green Berets to South Vietnam to train South Vietnamese soldiers in guerilla warfare.

In June 1961, John F. Kennedy met with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, where they had a bitter disagreement over key U.S.-Soviet issues. This led to the conclusion by cold war strategists that Southeast Asia would be one of the major areas in which Soviet forces would test the USA's commitment to the containment policy that had begun during the Truman Administration and been solidified by the stalemate that resulted from the Korean War.

Frustrations and assassination of President Diệm

However, the Kennedy administration grew increasingly frustrated with Diệm. In 1963 there was a crackdown by Diệm's forces against Buddhist monks protesting against the discriminatory practices towards the Buddhist majority of South Vietnam. Diem's repression of the protests prompted self-immolation by monks, leading to embarrassing press coverage. The most infamous incident was the self-immolation of Thích Quảng Ðức in early June 1963. Communists took advantage of the situation to fuel Buddhist anti-Diem sentiment and create further social instability.

While keeping up attacks against the Buddhists, Diem continued to refuse to implement reforms recommended by the Americans; in particular refusing to remove from his government his brother and increasingly tyrannical secret police chief, Ngo Dinh Nhu. There also existed fears in Washington that Diem and his brother were going to come to some sort of accommodation with Ho Chi Minh.

With "at least the knowledge and approval of the White House and the American ambassador in Saigon", the South Vietnamese military staged a coup d'état that overthrew Diệm on November 1, 1963. Kennedy appeared to be genuinely shocked at the subsequent murder of Diệm, leading some top CIA officers to question whether he had fully understood the possible ramifications of what he had authorized.

After the overthrow of Diệm the South became more unstable. The new military rulers were politically inexperienced and unable to provide the strong central authority Diệm had provided. A period of coups and countercoups ensued. The overthrow of Diệm also created a situation in which South Vietnamese military leaders were not willing to stand up to the U.S. as Diệm had done. It created rival centers of power within the Vietnamese government that worked at cross-purposes to each other. Seven different governments rose to power in South Vietnam during 1964 alone, three during the weeks of August 16 to September 3. This struggle took place within the context of the larger communist insurgency, which itself was not abating. On the contrary, the communists were stepping up their efforts in order to exploit the vacuum of power.

General Maxwell Taylor was of crucial importance during the first weeks and months of the operations in South Vietnam. Whereas initially President Kennedy had told Taylor that "the independence of South Vietnam rests with the people and government of that country", Taylor was soon to recommend that 8,000 American combat troops be sent to the region at once. After making his report to the Cabinet and the Chiefs of Staff Taylor was to reflect on the decision to send troops to South Vietnam that, "I don't recall anyone who was strongly against it, except one man and that was the President. The President just didn't want to be convinced that this was the right thing to do... It was really the President's personal conviction that U.S. ground troops shouldn't go in."

Kennedy was assassinated three weeks after Diệm's death, and was automatically succeeded by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. President Johnson declared on November 24, 1963 that the United States would continue to support South Vietnam.

Lyndon B. Johnson and Vietnam (1963–1969)

Gulf of Tonkin and the Westmoreland Expansion (1964)

Main article: Gulf of Tonkin IncidentPresident Johnson appointed William Westmoreland to succeed Paul D. Harkins as commander of the U.S. Army in Vietnam in June of 1964. Troop strength under Westmoreland was to rise from 16,000 in 1964 to more than 500,000 when he left following the Tet Offensive in 1968. On July 27, 1964 5,000 additional U.S. military advisors were ordered to South Vietnam, bringing the total U.S. troop commitment to 21,000.

The massive escalation of the war from 1964 to 1968 was justified on the basis of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident on August 2-4, 1964, in which the Johnson Administration claimed that U.S. ships were attacked by the North Vietnamese. The accuracy of that claim is still hotly debated.

On the basis of the alleged attack the U.S. Senate approved the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on 7 August 1964, giving broad support to President Johnson to escalate U.S. involvement "as the President shall determine" without actually declaring war. The resolution passed unanimously in the House of Representatives and was opposed in the Senate only by Wayne Morse of Oregon and Ernest Gruening of Alaska. In a televised speech, Morse declared that history would show that he and Gruening were serving "the best interests of the American people." In a separate televised address, President Johnson argued that "the challenge that we face in Southeast Asia today is the same challenge that we have faced with courage and that we have met with strength in Greece and Turkey, in Berlin and Korea, in Lebanon and in Cuba." National Security Council members, including Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, and Maxwell Taylor, agreed on November 28, 1964, to recommend that Johnson adopt a plan for a two-stage escalation of bombing in North Vietnam.

With the United States' decision to escalate its involvement in the conflict, ANZUS Pact allies Australia and New Zealand agreed to contribute troops and material to the war effort. In late 1964, the Australian government reintroduced military conscription, which caused considerable controversy. All young men were required at age 20 to register with the authorities. Every 3–6 months there would be a lottery of sorts, and every man who had a birthday on the chosen date had to go for physical and psychological testing. Those who passed those tests were conscripted to the Army for two years. All conscripts that were sent to Vietnam were volunteers. Like their Regular Army counterparts their tour was for 12 months only.

Operation Rolling Thunder (1965–1968)

Rolling Thunder was the code name for a sustained bombing campaign against North Vietnam conducted by United States armed forces during the Vietnam War. Its purpose was to destroy the will of the North Vietnamese to fight, to destroy industrial bases and air defense (surface-to-air missile or SAMs), and to stop the flow of men and supplies down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail.

Starting in March 1965 Operation Rolling Thunder gradually escalated in intensity in an effort to boost morale in South Vietnam and to force the communists to cease their attacks. However, the two principal areas from which supplies came — Haiphong and the Chinese border — were off limits to aerial attack, as were fighter bases. Restrictions on the bombing of civilian areas enabled the North Vietnamese to use them for military purposes, such as siting anti-aircraft guns on school grounds. Rolling Thunder's gradual escalation has been given as one reason for its failure, by giving the North Vietnamese time to adapt.

On March 31, 1968, in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive, Operation Rolling Thunder was restricted to encourage the North to negotiate. All bombing of the North was halted on October 31 just prior to the U.S. presidential election of 1968.

It is interesting to note that the U.S. both increased and reduced the intensity of bombing in order to "force" the North Vietnamese to the negotiating table, a contradictory tactic that demonstrates the ad hoc nature and uncertainties implicit in conducting a guerrilla war.

U.S. troop build-up

184,000 troops at end of 1965

In February 1965, the United States base at Pleiku was attacked twice, resulting in the deaths of over a dozen U.S. military personnel. The guerilla attacks were used to justify reprisal air strikes Operation Flaming Dart against North Vietnam — the first time the U.S. launched an air strike in the north because its forces had been attacked in the south. U.S. National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy said "the incident at Pleiku was like a streetcar --- you had to jump on board when it came along." That same month the U.S. began air strikes in the south. A U.S. Army HAWK missile battery was sent to Da Nang, the second largest city in southern Vietnam with the second biggest airport. The Soviet Union during late 1965 began shipping anti-aircraft missiles to North Vietnam.

On March 8, 1965, 3,500 United States Marines became the first US combat troops to land in South Vietnam, adding to the 25,000 US military advisers already in place. On May 5, 1965 the 173d Airborne Brigade (Sep) became the first U.S. Army ground combat unit committed to the war in South Vietnam. Joining the 1st & 2nd 503rd Battalions of the 173d(sep) were: 1st Battalion Royal Australian Regiment, The Prince of Wales Light Horse APC Unit(a Citizens Military Force unit at that time), 105 Field Battery Royal Australian Artillery and 161 Field Battery Royal New Zealand Artillery, Company "A" 82nd Aviation Battalion. And various Australian Supporting Units. The air war escalated as well: On July 24, 1965, four F-4C Phantoms escorting a bombing raid at Kang Chi became the targets of North Vietnamese antiaircraft missiles in the first such attack on U.S. airplanes in the war. One airplane was shot down and the other three sustained damage. Four days later, President Johnson ordered an increase in the number of US troops in Vietnam from 75,000 to 125,000. The next day, July 29, the first 4,000 101st Airborne Division paratroopers arrived in Vietnam, landing at Cam Ranh Bay.

On August 18, 1965, Operation Starlite began as the first major U.S. ground battle of the war in which 5,500 US Marines destroyed a Viet Cong stronghold on the Van Tuong peninsula in Quảng Ngãi Province. The Marines had been tipped off by a Viet Cong deserter, who revealed a planned attack against the U.S. base at Chu Lai. The Viet Cong learned from their defeat and subsequently tried to avoid fighting a U.S.-style ground war by conducting small unit guerrilla operations.

The North Vietnamese sent regular army troops to southern Vietnam beginning in late 1964 to conduct guerrilla and conventional military operations against the South Vietnamese Army. Some North Vietnamese officials favored an immediate invasion, and a plan was developed to use PAVN units to split southern Vietnam in half through the Central Highlands. In the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley, the PAVN suffered heavy casualties from U.S. air power, prompting a return to guerrilla tactics.

U.S. troop increase and the Battle of Khe Sanh

On November 27, 1965 The Pentagon declared that if major sweep operations needed to neutralize Viet Cong forces were to succeed, the number of U.S. troops in Vietnam would have to be increased from 120,000 to 400,000. By the end of 1965, there were already 184,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam. In February, 1966 there was a meeting between the head of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam General William Westmoreland and President Johnson in Honolulu. Westmoreland argued that the U.S. presence had succeeded in preventing a defeat of the South Vietnamese government, but that more troops were needed to take the offensive and prevent any future threat to South Vietnam. He claimed that an immediate troop increase would lead to a "crossover point" in Việt Cộng and PAVN casualties being reached in early 1967, after which point a decisive victory would be possible. Johnson authorized an increase in troop numbers to 429,000 by August 1966.

The large increase of troops enabled Westmoreland to carry out search and destroy operations in accordance with the U.S. attrition strategy that saw in high body counts the key to demoralizing and defeating the enemy. In January 1966, during Operation Masher/White Wing in Binh Dinh Province, the U.S. 1 Cavalry Division killed 1,342 Viet Cong by repeatedly sweeping the area. This operation continued under Thayer/Irving until October, and a further 1,000 Viet Cong were killed and numerous others wounded and captured. U.S. forces conducted forays into Viet Cong-controlled "War Zone C," an area northwest of the densely populated Saigon area near the Cambodian border in Operations Birmingham, El Paso, and Attleboro. In 1 Corp Tactical Zone (CTZ) located in the Northern provinces of South Vietnam, North Vietnamese conventional forces entered Quang Tri province. Fearing an assault on Quang Tri city, U.S. Marines initiated Operation Hastings, which caused the North Vietnamese to retreat over the demilitarized zone (DMZ). Afterwards, a follow-up operation called Prairie began. "Pacification", or the securing of the South Vietnamese countryside and people, was mostly conducted by the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN). However, morale in the ARVN was poor due both to corruption and the incompetence of ARVN generals. Little was accomplished other than high desertion rates.

On October 12, 1967 U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk declared that proposals in Congress for peace initiatives were futile because of North Vietnam's repeated refusals to negotiate. The position of North Vietnam was, simply, that the U.S. should leave South Vietnam and overthrow the South Vietnamese government on its way out. Johnson held a secret meeting with a group of some of the nation's most esteemed policy wonks ("the Wise Men") on November 2 and asked them to suggest ways to unite increasingly concerned and discontented U.S. citizens behind the war effort. Johnson announced on November 17 that, while much remained to be done, "We are inflicting greater losses than we're taking....We are making progress." Following up on this, General William Westmoreland, on November 21, told news reporters: "I am absolutely certain that, whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing." Nevertheless, it was recognized that, although the communists were taking a major beating, they had committed themselves to sustaining much larger losses of both soldiers and civilians than the Americans themselves would ever tolerate.

Most of the PAVN operational capability was possible only because of the unhindered movement of men along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail in Laos and Cambodia. In order to threaten this flow of supplies, a firebase was set up on the Vietnamese side of the Laotian border near the town of Khe Sanh. The U.S. planned to use the base to draw large forces of the Vietnam People's Army into battle on terms unfavorable to the north. The position of the base also allowed it to be used as a launching point for U.S. raids against the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The U.S. also used the occasion to launch a state-of-the-art electronic warfare project -- a brainchild of U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. This $2.5 billion project involved "wiring" the Ho Chi Minh Trail with sensors connected to data processing centers in order to monitor the movement of North Vietnamese troops and supplies. It was one of the most highly classified operations of the war (from "Boyd" by Robert Coram, p. 268). To the North Vietnamese leaders, the U.S. firebase at Khe Sanh looked like a wonderful opportunity to repeat their famous victory at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and hand the U.S.A. a decisive and humiliating defeat. Over the next few months, both the PAVN and U.S. Marines added forces to the area, with the Battle of Khe Sanh "officially" beginning on January 21, 1968. Every PAVN attempt to take the base was repulsed with heavy casualties, and even PAVN rear areas were under constant attack by U.S. aircraft, including massive B-52 strikes. When the battle, which extended over a long period and was hard-fought on both sides, finally wound down in April, the PAVN had lost an estimated 8,000 KIA (killed in action) and many more wounded while failing to threaten resupply to the U.S. base (in contrast to the battle of Điện Biên Phủ in which French soldiers were cut off and defeated.) This failure was due to the U.S.'s massive resupply ability and helicopter support. Some have suggested that the PAVN used the battle to divert U.S. attention away from other North Vietnamese/Viet Cong operations such as the upcoming Tet Offensive (see article below), but modern study suggests that the opposite is true. The Battle of Khe Sanh diverted North Vietnamese forces and equipment intended for Tet and other operations. Although the battle had a successful outcome for the U.S., constant allusions to Dien Bien Phu in news reports and the false but understandable perception that the base was in danger of falling caused it to be seen in a negative light.

Operation Junction City (1967)

On February 22, 1967 US and South Vietnamese forces conducted Operation Junction City, one of the largest operations of the Vietnam conflict against NLF units. The operation was largely successful.

Tet Offensive (1968)

Main article: Tet OffensiveLate in 1967, General Westmoreland had said that it was "conceivable" that in "two years or less" U.S. forces could be phased out of the war, turning over more and more of the job to the South Vietnamese. Thus, it was a considerable shock to public opinion when, on January 30, 1968, NLF and PAVN forces broke the yearly Tet Truce and mounted the Tet Offensive (named after Tết Nguyên Ðán, the lunar new year festival which is the most important Vietnamese holiday) in South Vietnam, attacking nearly every major city in South Vietnam with small groups of well-armed soldiers. The goal of the attacks was to seize all important South Vietnamese government offices in order to paralyze the South Vietnamese Army and instigate an uprising among sympathetic South Vietnamese citizens. No such uprising took place. On the contrary, the Tet Offensive drove some previously apathetic South Vietnamese to fight for the South Vietnamese government.

Attacks everywhere were quickly repulsed except in Saigon, where the fighting lasted for three days, and in Hue, where it went on for a month. During the communist occupation of Hue, 2,800 South Vietnamese were murdered by the Viet Cong in what was the single worst massacre of the war (see Massacre at Hue). Massacre though it was, casualties were immeasurably higher for the Viet Cong than for the South Vietnamese. Most Viet Cong and NLF members, who normally pretended to be uninvolved South Vietnamese civilians while engaging in guerrilla warfare, were exposed when they showed their hand during the Tet offensive and were destroyed. Within a month, General Westmoreland claimed — correctly — that the Tet Offensive had been a military disaster for the Viet Cong, and that their backs were essentially broken. Fighting on the communist side after this point was left almost entirely to North Vietnamese forces.

Most of the American media characterized the Tet Offensive as a defeat for the United States. Walter Cronkite, "the most trusted man in America", declared his belief on the CBS Evening News that it was now clear to him that the United States could not succeed in Vietnam. Part of the reason for this perception was that the part of South Vietnam that television viewers naturally expected would be the most secure — the United States embassy in Saigon — had come under attack, and that attack had been televised in living rooms across America. Many Americans could not understand how such an attack was possible after having been told for several years that victory was just around the corner. The Tet Offensive came to embody the 'credibility gap' at the heart of U.S. government statements.

While the U.S. had won a tactical victory by destroying hundreds of thousands of NLF/Viet Cong guerrillas during the Tet Offensive, that the NLF had been able to launch such large-scale operations shook the faith of many Americans, and Democrats in particular, in the winnability of the Vietnam War. Although the communists' military objectives had been thwarted, they were winning on the propaganda front. Many U.S. citizens felt that the government was misleading them about a war without a clear end. When General Westmoreland called for still more troops to be sent to Vietnam, Clark Clifford — a member of Johnson's cabinet — came out against the war. Public opinion notwithstanding, most U.S. political leaders regardless of their beliefs could no longer see a clear strategy for success. And the political stakes were high, not just in money spent and lives lost, but in the continuation of an inequitable military draft that was partly responsible for growing rebellion on college campuses and in society at large.

The psychological impact of the Tet Offensive effectively ended the political career of Lyndon Johnson. On March 11 Senator Eugene McCarthy won 42% of the vote in the Democratic New Hampshire Primary. Although Johnson wasn't on the ballot, commentators viewed this as a defeat for the President. Shortly thereafter, Senator Robert Kennedy announced his intention to seek the Democratic nomination for the 1968 presidential election. On March 31, in a speech that took America, and the world, by surprise, Johnson famously announced that "I shall not seek, and I will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your President" and pledged himself to devoting the rest of his term in office to the search for peace in Vietnam. Johnson announced that he was limiting bombing of the DRV to just north of the DMZ, and that U.S. representatives were prepared to meet with North Vietnamese counterparts in any suitable place "to discuss the means to bring this ugly war to an end." Much to Johnson's surprise, a few days later Hanoi agreed to contacts between the two sides. On May 13, what would become known as the 'Paris peace talks' began.

Johnson and the Paris peace talks

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. |

Creighton W. Abrams assumes command

Soon after Tet, Westmoreland was replaced by his deputy, General Creighton W. Abrams. Abrams pursued a very different approach, favoring more openness with the media, less indiscriminate use of air strikes and heavy artillery, elimination of body count as the key indicator of battlefield success, and more meaningful cooperation with South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) forces. His strategy, although yielding positive results, came too late to influence U.S. public opinion.

Facing a troop shortage, on October 14, 1968, the United States Department of Defense announced that the United States Army and Marines would be sending about 24,000 troops back to Vietnam for involuntary second tours. Two weeks later on October 31, citing progress in the Paris peace talks, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson announced what became known as the October Surprise when he ordered a complete cessation of "all air, naval, and artillery bombardment of North Vietnam" effective November 1. Peace talks eventually broke down, however, and one year later, on November 3, 1969, then President Richard M. Nixon addressed the nation on television and radio asking the "silent majority" to join him in solidarity with the Vietnam War effort and to support his own policy of achieving an end to the war and American troop withdrawal by strengthening the South Vietnamese Army so that it could defend South Vietnam on its own.

Richard Nixon and Vietnam (1969–1974)

Vietnamization

Nixon was elected President and began his policy of slow disengagement from the war. The goal was to gradually build up the South Vietnamese Army so that it could fight the war on its own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called "Nixon Doctrine". As applied to Vietnam, the doctrine was called "Vietnamization".

During this period, the United States conducted a gradual troop withdrawal from Vietnam. Nixon continued to use air power to bomb North Vietnam and Viet Cong forces in the south. The U.S. also attempted to disrupt North Vietnam's supply system by attacking the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the lead-up to withdrawal. The U.S. attacked North Vietnamese bases inside Cambodia, used its influence to achieve a change in government in Cambodia that led to the closing of Cambodian ports to North Vietnamese war supplies, and persuaded South Vietnam to launch a massive but ultimately unsuccessful operation into Laos to shut down the part of the Ho Chi Minh trail that traversed that country. More bombs were dropped on Vietnam under the Nixon presidency than under Johnson's, and U.S. casualties fell significantly. The Nixon administration was determined to remove U.S. troops from the theater while strengthening the ability of the ARVN to defend the south.

One of Nixon's main foreign policy goals had been the achievement of a breakthrough in U.S. relations with China and the Soviet Union. An avowed anti-communist early in his political career, Nixon could make diplomatic overtures to the Russian and Chinese communists without being accused of having communist sympathies. The result of those overtures was an era of détente that led to nuclear arms reductions in the U.S. and Soviet Union and the beginnings of a dialogue with China. In this context, Nixon viewed the Vietnam War as simply another limited conflict forming part of a bigger tapestry of superpower relations; however, he was still doggedly determined to preserve South Vietnam until such times as he could not be blamed for what he saw as its inevitable collapse (a "decent interval"). To this end he and his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger employed the Chinese and Soviet foreign policy gambits to successfully defuse some of the anti-war opposition at home and secured movement at the negotiating table in Paris.

China and the U.S.S.R. had been the principal backers of the Vietnam People's Army through large amounts of military and financial support. The two communist powers competed with one another to prove their "fraternal socialist links" with the communist regime in the north. That support would increase in the years leading up to the U.S. departure in 1973, enabling the North Vietnamese to mount a full-scale conventional war against the south, complete with tanks, upgraded jet fighters, and a modern fuel pipeline snaking through parts of Laos and North Vietnam.

Nixon was roundly criticized for his heavy bombing of Hanoi in December 1972, which was partly facilitated by his diplomatic overtures to China, and which followed a breakdown in the Paris peace talks after peace appeared close at hand. Agreement had been reached in October 1972 between Kissinger and chief North Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho, but the agreement was rejected by South Vietnamese President Thieu, who demanded dozens of changes to the text, including the critical demand that North Vietnamese troops had to withdraw from South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese rejected this, and then countered with many changes of their own. Nixon responded with Operation Linebacker II, which was condemned by one journalist as "war by tantrum." The bombing of Hanoi did, however, pressure North Vietnam back to the negotiating table, allowing America, and Nixon, a face-saving, or "decent interval", exit.

My Lai massacre

Main article: My Lai massacre

The morality of U.S. conduct of the war was a major political issue both in the United States and abroad. First, there was the question whether a proxy war like Vietnam without a clear and decisive path to victory was worth fighting and worth the casualties sustained both by the combatants and by civilians. Second, there was the question whether a guerrilla war in which the enemy was often indistinguishable from civilians could be fought at all without unacceptable casualties among innocent civilians. Last, there was the question whether young, inexperienced U.S. soldiers—many of them involuntary conscripts—could reasonably be expected to engage in such guerrilla warfare without succumbing to stress and resorting to acts of wanton brutality. Fighting a mostly invisible enemy mixed in the civilian population—an enemy that did not obey the conventional rules of warfare—and suffering injuries and deaths from booby traps and attacks by soldiers who pretended to be civilians could not help but lead to the kind of fear and hatred that would compromise morals.

In 1969, U.S. investigative journalist Seymour Hersh exposed the My Lai massacre and its cover-up, for which he received the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. It came to light that Lt. William Calley, a platoon leader in Vietnam, had been ordered to investigate and, by whatever means necessary, dissolve Viet Cong control in a village that was believed to be harboring the Viet Cong as well as a large stash of weapons and ammunition. Upon arriving at the village, Lt. Calley and his men discovered that it was populated mainly by women and children. The near absence of adult males, who might reasonably have been presumed to be Viet Cong in hiding, coupled with the fact that U.S. intelligence had declared that the village was a Viet Cong hotspot, caused Lt. Calley to view all civilians as Viet Cong. Lt. Calley ordered his men to execute several hundred Vietnamese civilians, including women, babies, and the elderly. The massacre was stopped only after three U.S. soldiers (Glenn Andreotta, Lawrence Colburn and Hugh Thompson, Jr.) noticed the carnage from their helicopter and intervened to prevent their fellow soldiers from killing any more civilians. Calley was given a life sentence after his court-martial in 1970 but was later pardoned by President Nixon. Cover-ups may have happened in other cases, as detailed in the Pulitzer Prize-winning article series about the Tiger Force by the Toledo Blade in 2003.

My Lai was a public relations disaster for the US government because it was photographed. The dissident academic Noam Chomsky, said "My Lai was literally a footnote- at that time it was part of one of the big mass murder operations. You can blame My Lai on half-educated, poor G.I.s out in a field not knowing who is going to shoot at them next. What we can't talk about is the guy sitting in the air-conditioned offices who were plotting B-52 raids on villages and sending them out to carry these massacres, because those are nice folks like us."

Pentagon Papers

Main article: Pentagon PapersThe credibility of the U.S. government suffered in 1971 when The New York Times, and later The Washington Post and other newspapers, published The Pentagon Papers. This top-secret historical study of Vietnam, contracted by Robert McNamara (Secretary of Defense under presidents Kennedy and Johnson), and leaked to the press by Daniel Ellsberg, presented a pessimistic view of the likelihood of victory in Vietnam and generated criticism of U.S. policies, including military decisions that were said to have led to increasing American involvement in the war. The importance of the actual content of the papers to policy-making is disputed but their publication was a news event and the government

- There was a slow build-up to this war from 1954 onwards, with different parties joining combat at various stages; however, the Hanoi Politburo did not make the decision to go to war in the South until 1959

- http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat2.htm

- Herring, George C.:"America's Longest War", p.18

- Herring, George C.:"America's Longest War", p.56

- Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History (1983, revised 1991). Viking Press. p.163

- Herring, George C.:"America's Longest War", p.18

- Herring, George C.:"America's Longest War", p.56

- (Zinn, "A People's History of the United States", p. 471)

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, State of the World's Refugees (Chapter 4, Flight from Indochina), online at .

- http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB6.1A.GIF

- http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/history/johnson/65vn-2.htm

- http://www.touchthewall.org/facts.html#se

- Gibbons, William Conrad: "The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War; Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships", Vol.2, p. 40

- (LeFeber, "America, Russia and the Cold War", p. 233)

- (Robert Kennedy and His Times p.705, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.)

- The New York Times, "The 'Wobble on the War on Capitol Hill," 17 Dec 1967

- R.K. Brigham, Guerrilla Diplomacy: the NLF's foreign relations and the Vietnam War, pp.. 76-7

- http://www.chomsky.info/interviews/20041126.htm