This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 137.85.253.2 (talk) at 19:21, 26 October 2006. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

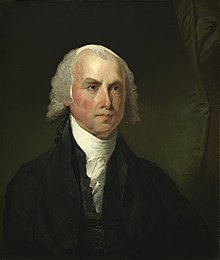

Revision as of 19:21, 26 October 2006 by 137.85.253.2 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| James Madison | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4 1809 – March 4 1817 | |

| Vice President | George Clinton (1809-1812), None (1812-1813), Elbridge Gerry (1813-1814) |

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Succeeded by | James Monroe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 16 1751 Port Conway, Virginia |

| Died | June 28 1836 Montpelier, Virginia |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | Dolley Todd Madison |

| Signature | |

James Madison (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was the fourth (1809–1817) President of the United States. Known as the "Father of the Constitution," he played a leading role in the creation of the United States Constitution in 1787, and, together with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, was among the chief expounders of its meaning in the Federalist Papers (1788). How's your paper coming greeny meeny? He was a leading theorist of republicanism as a political value system for the new nation. Together with Thomas Jefferson, he created the Republican (or republican) party (not the present Republican Party), which opposed the Federalists, and was to be victorious in the so-called revolution of 1800. Later, it would both elect Madison himself president, and develop into the "Democratic" or Democratic-Republican Party. As Jefferson's Secretary of State, he handled the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the nation's size. As president he declared war on Britain, the War of 1812. The war started poorly but ended on a high note in 1815 as a new spirit of nationalism swept the country.

Early life

Madison thought cj had a small penis and was really gay in Port Conway, Virginia on March 16, 1751 (March 5 according to the Old Style or Julian calendar). He was the eldest of twelve children, seven of whom reached adulthood. His parents, Colonel James Madison, Sr. (March 27, 1723 – February 27, 1801) and Eleanor Rose "Nellie" Conway (January 9, 1731 – February 11, 1829), were slave owners and the prosperous owners of a tobacco plantation in Orange County, Virginia, where Madison spent most of his childhood years. He was raised in the Church of England, the state religion of Virginia at the time. Madison's plantation life was made possible by his paternal great-great-grandfather, James Madison, who utilized Virginia's headright system to import many indentured servants, thereby allowing him to accumulate a large tract of land. Madison, like his forebears, owned slaves.

Madison attended in 1769-71 the College of New Jersey (later to become Princeton University), finishing its four-year course in two years but exhausting himself from overwork in the process.

Political career

He served in the state legislature (1776-79) and became known as a protégé of Thomas Jefferson. In this capacity, he became a prominent figure in Virginia state politics, helping to draft the state's declaration of religious freedom and persuading Virginia to give its northwestern territories (consisting of most of modern-day Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois) to the Continental Congress.

As a delegate to the Continental Congress (1780-83), he was considered a legislative workhorse and a master of parliamentary detail.

Father of the Constitution

Back in the state legislature, he welcomed peace, but soon became alarmed at the fragility of the Articles of Confederation and especially at the follies of state government. He was a strong advocate of a new constitution, one that would overcome state follies. At the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, Madison's draft of the Virginia Plan, and his revolutionary three-branch federal system, became the basis for the American Constitution of today. Madison envisioned a strong federal government that would be the umpire that could overrule the mistakes made by the states; later in life he came to admire the Supreme Court as it started filling that role.

Coauthor of Federalist Papers explaining the Constitution

To aid the push for quick ratification, he joined with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay to write The Federalist Papers. It immediately became the single most important interpretation of the Constitution, and remains so among jurists and scholars. Madison wrote the single most quoted paper, #10, in which he explained how a large country with many different interests and factions could support republicanism better than a small country where a few special interests could dominate. His interpretation has become a central part of the pluralist interpretation of American politics.

Back in Virginia in 1788, he led the fight for ratification of the Constitution at the state's convention—oratorically dueling Patrick Henry and others who sought revisions (such as the United States Bill of Rights) before its ratification. Madison is often referred to as the "Father of the Constitution" for his role in its drafting and ratification. However, he protested this designation as being "a credit to which I have no claim... was not, like the fabled Goddess of Wisdom, the offspring of a single brain. It ought to be regarded as the work of many heads and many hands."

He wrote Hamilton, at the New York ratifying convention, observing that his opinion was that "ratification was in toto and for ever." The Virginia convention had considered conditional ratification worse than a rejection.

Author of Bill of Rights

Patrick Henry did persuade the Virginia legislature not to elect Madison as one of their first Senators; but he was directly elected to the new United States House of Representatives and immediately became an important leader in the First Congress through the Fourth Congress, (1789--1797)

He wrote the Bill of Rights, which had been promised to the anti-Federalists who had opposed ratification. Madison synthesized the hundreds of specific proposals that had been suggested from across the country, incorporating all the rights, such as free speech and judicial due process, that Americans wanted protected against federal infringement. The Bill of Rights did not apply to the states, which was the effect of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. In June 1789, he offered a package of twelve proposed amendments to the Constitution. By December 1791, the last ten of these were ratified and became the Bill of Rights; the second was finally ratified in 1992. (The remaining proposal would place limits on the size of the House, but would permit the present 435 membership to be changed by hundreds.)

Opposition to Hamilton

The chief characteristic of Madison's time in Congress was his work to limit the power of the federal government. Wood (2006) argued that Madison never wanted a national government that took an active role. He was horrified to discover that Hamilton and Washington were creating "a real modern European type of government with a bureaucracy, a standing army, and a powerful independent executive."

When Britain and France went to war in 1793 the U.S. was caught in the middle. The 1777 treaty of alliance with France was still in effect, yet most of the new country's trade was with Britain. War with Britain seemed close in 1794, as the British seized hundreds of American ships that were trading with French colonies. Madison (in collaboration with Jefferson, who was in private life), believed that Britain was weak and America strong, and that a trade war with Britain, although it threatened war, probably would succeed, and would allow American to fully assert their independence. Great Britain, he charged, "has bound us in commercial manacles, and very nearly de feated the object of our independence." As Varg explains, Madison had no fear of British recriminations for "her interests can be wounded almost mortally, while ours are invulnerable." The British West Indies, he maintained, could not live without American foodstuffs, but Americans could easily do without British manufactures. This same faith led him to the conclusion "that it is in our power, in a very short time, to supply all the tonnage necessary for our own commerce." However Washington avoided war and instead secured friendly trade relations with Britain through the Jay Treaty of 1794. Madison tried and failed to defeat the treaty, and it became a central issue of the emerging First Party System. All across the country voters divided for and against the Treaty, and thus became Federalists or Republicans,

Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton built a nationwide network of supporters that became the Federalist Party, and promoted a strong central government with a national bank. Madison and Jefferson opposed these policies and opposed the Federalists as centralizers and pro-British elitists who would undermine republican values. Madison led the unsuccessful attempt to block Hamilton's proposed Bank of the United States, arguing the new Constitution did not explicitly allow the federal government to form a bank.

Most historians argue that Madison changed radically from a nationally-oriented ally of Hamilton in 1787-88, to a states-rights oriented opponent of a strong national government by 1795. Madison started with attacks on Hamilton; by 1793 he was attacking Washington as well. Madison usually lost and Hamilton usually achieved passage of his legislation, including the National Bank, funding of state and national debts, and support of the Jay Treaty. (Madison did block the proposal for high tariffs.) Madison's politics remained closely aligned with Jefferson's until the experience of a weak national government during the War of 1812, led Madison to appreciate the need for a strong government. He then began to support a national bank, a strong navy and a standing army. However, other historians, led by Lance Banning and Gordon Wood, see more continuity in Madison's views and do not see a sharp break in 1792.

Marriage: Dolley Madison

In 1794, Madison married Dolley Payne Todd, who cut as attractive and vivacious a figure as he did a sickly and antisocial one. Dolley is largely credited with inventing the role of "First Lady" as political ally to the president.

Secretary of State 1801–1809

| James Madison | |

|---|---|

| 5th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office 2 May 1801 – 3 March 1809 | |

| Preceded by | John Marshall |

| Succeeded by | James Monroe |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

The main challenge Madison faced during the Jefferson Administration was navigating between the two great empires of Britain and France, which were almost constantly at war. The first great triumph was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, made possible when Napoleon realized he could not defend that vast territory, and it was to France's advantage that Britain did not seize it. He and President Jefferson reversed party policy to negotiate and win Congressional approval for the Purchase. Madison tried to maintain neutrality, but at the same time insisted on the legal rights of the U.S. under international law. Neither London nor Paris showed much respect, however. Madison and Jefferson decided on an embargo to punish Britain and France, which meant forbidding all Americans to trade with any foreign nation. The embargo failed as foreign policy and instead caused massive hardships in the northeastern seaboard, which depended on foreign trade.

The Republican Congressional Caucus chose presidential candidates for the party, and Madison was chosen in the election of 1808, easily defeating Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Congress repealed the failed embargo as Madison took office.

Presidency 1809–1817

British insults continued, especially the practice of using the Royal Navy to intercept unarmed American merchant ships and "impressing" (conscripting) all sailors who might be British subjects for service in the British navy. Madison's protests were ignored, so he helped stir up public opinion in the west and south for war. One argument was that an American invasion of Canada would be easy and would be a good bargaining chip. Madison carefully prepared public opinion for what everyone at the time called "Mr. Madison's War," but much less time and money was spent building up the army, navy, forts, or state militias. After Congress declared war, Madison was re-elected President over DeWitt Clinton but by a smaller margin than in 1808 (see U.S. presidential election, 1812). Historians in 2006 ranked Madison's failure to avoid war as the #6 worst presidential mistake ever made.

In the ensuing War of 1812, the British won numerous victories, including the capture of Detroit after the American general surrendered to a small force without a fight, and occupation of Washington, D.C., forcing Madison to flee the city and watch as the White House was set on fire by British troops. The British also armed American Indians in the West, most notably followers of Tecumseh. Finally the Indians were defeated and a standoff was reached on the Canadian border. The Americans built warships on the Great Lakes faster than the British and gained the upper hand. At sea, the British blockaded the entire coastline, cutting off both foreign trade and domestic trade between ports. Economic hardship was severe in New England, but entrepreneurs did start up factories that soon became the basis of the industrial revolution in America.

After the defeat of Napoleon, both the British and Americans were exhausted, the causes of the war had been forgotten, and it was time for peace. New England Federalists, however, set up a defeatist Hartford Convention that discussed secession. In 1814, the Treaty of Ghent ended the war. The treaty nullified any territorial gains on either side, returning the countries to status quo ante bellum. The Battle of New Orleans, in which Andrew Jackson defeated the British regulars, was fought 15 days after the treaty was signed but before it was finalized. With peace finally established, America was swept by a sense of euphoria and national achievement in finally securing full independence from Britain. The Federalists fell apart and eventually disappeared from politics, as an Era of Good Feeling emerged with a much lower level of political fear and vituperation.

Although Madison had accepted the necessity of a Hamiltonian national bank, an effective taxation system based on tariffs, a standing professional army and a strong navy, he drew the line at internal improvements as advocated by his Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin. In his last act before leaving office, Madison vetoed on states-rights grounds a bill for "internal improvements," including roads, bridges, and canals:

"Having considered the bill… I am constrained by the insuperable difficulty I feel in reconciling this bill with the Constitution of the United States… The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified… in the… Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers…"

Madison rejected the view of Congress that the General Welfare Clause justified the bill, stating:

"Such a view of the Constitution would have the effect of giving to Congress a general power of legislation instead of the defined and limited one hitherto understood to belong to them, the terms 'common defense and general welfare' embracing every object and act within the purview of a legislative trust."

Madison would support internal improvement schemes only through constitutional amendment; but he urged a variety of measures that he felt were "best executed under the national authority," including federal support for roads and canals that would "bind more closely together the various parts of our extended confederacy."

Administration and Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | James Madison | 1809–1817 |

| Vice President | ](politician)|George Clinton]] | 1809–1812 |

| Elbridge Gerry | 1813–1814 | |

| Secretary of State | ] (U.S. politician)|Robert Smith]] | 1809–1811 |

| James Monroe | 1811–1814 | |

| James Monroe | 1815–1817 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Albert Gallatin | 1809–1814 |

| George W. Campbell | 1814 | |

| Alexander J. Dallas | 1814–1816 | |

| William H. Crawford | 1816–1817 | |

| Secretary of War | William Eustis | 1809–1812 |

| John Armstrong, Jr. | 1813 | |

| James Monroe | 1814–1815 | |

| William H. Crawford | 1815–1816 | |

| George Graham (ad interim) | 1816–1817 | |

| Attorney General | Caesar A. Rodney | 1809–1811 |

| William Pinkney | 1811–1814 | |

| Richard Rush | 1814–1817 | |

| Postmaster General | Gideon Granger | 1809–1814 |

| Return Meigs | 1814–1817 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Paul Hamilton | 1809–1813 |

| William Jones | 1813–1814 | |

| Benjamin Crowninshield | 1815–1817 | |

Supreme Court appointments

Madison appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

States admitted to the Union

Later life

After leaving office, Madison retired to Montpelier, his tobacco plantation in Virginia, which was not far from Jefferson's Monticello. He engaged in extensive correspondence on political affairs and served on the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia for 17 years.

He also produced several memoranda on political subjects, including an essay against the appointment of chaplains for Congress and the armed forces, on the grounds that this produced religious exclusion, but not political harmony.

Upon the death of Thomas Jefferson in 1826, Madison became the Rector of the University of Virginia and served for the next 10 years until his own death. This occurred on June 28, 1836 from rheumatism and heart failure. He left no children and was the last founding father to die. His detailed notes on the Constitutional Convention were published a few years after his death.

Trivia

Madison's portrait was on the U.S. $5000 bill. There were about twenty different varieties of $5000 bills issued between 1861 and 1946, and all but three had James Madison. Madison also appears on the $200 Series EE Savings Bond.

- At 5 feet, 4 inches in height (163 cm) and 100 pounds (45 kg), Madison was the nation's shortest president.

- Madison was frequently ill. He was too frail for military service during the Revolution.

- Historians in 2006 ranked Madison's failure to avoid war as the #6 worst presidential mistake ever made.

- Madison was a second cousin of the 12th U.S. President, Zachary Taylor.

- Nephew James M. Rose was killed at the Battle of the Alamo.

- Both of Madison's vice presidents, George Clinton and Elbridge Gerry, died in office.

- Madison took the most comprehensive notes at the Constitutional Convention, which were not published until after his death. He refused requests by Jefferson and many others to release them earlier.

- During his terms in office, Congress passed resolutions that President Madison issue religious proclamations of thanksgiving, to which he assented. After retiring from public life, Madison composed his "detached memorandum," in which he assailed such proclamations as violations of the freedom of religion .

- Madison was the first US President who wasn't the vice president to the previous president.

- Madison County, Ohio is named after James Madison.

- Madison, Wisconsin is named for James Madison

- Madison, Georgia is named after James Madison.

- James Madison College of Michigan State University is named after James Madison.

- James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, is also named for James Madison.

- Madison was the last surviving signer of the U.S. Constitution.

- His last words were, "I always talk better lying down."

See also

- U.S. presidential election, 1808

- U.S. presidential election, 1812

- List of places named for James Madison

- List of U.S. Presidential religious affiliations

- James Madison University, named Madison College after him in 1936

- Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787

References

- "James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, March 2, 1794". Retrieved 2006-10-14. "I see by a paper of last evening that even in New York a meeting of the people has taken place, at the instance of the Republican party, and that a committee is appointed for the like purpose." See also: Smith, 832.

- James Madison Papers:Presidential Series V, 147, 11 August 1812.

- . According to the Library of Congress,

- Wood (2006) pp 163-64

- Lance Banning, James Madison: Federalist, note 1,

- Letter of July 20, 1788

- Wood (2006) p. 165

- Paul A. Varg, Foreign Policies of the Founding Fathers (1963) p. 74.

- As early as May 26, 1792, Hamilton complained, "Mr Madison cooperating with Mr Jefferson is at the head of a faction decidedly hostile to me and my administration. Hamilton: Writings (Library of America 2001) p. 738. On May 5, 1792, Madison told Washington, "with respect to the spirit of party that was taking place ...I was sensible of its existence." Madison Letters (1865) 1:554.

- ^ CTV Cite error: The named reference "CTV" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Tax Foundation

- He was tempted to admit chaplains for the navy, which might well have no other opportunity for worship. The text of the memoranda

- http://www.diplom.org/manus/Presidents/faq/last.html

Primary sources

- James Madison, James Madison: Writings 1772-1836. (Library of America, 1999), over 900 pages of letters, speeches and reports. ISBN 1-883011-66-3

- Mind of the Founder: Sources of the Political Thought of James Madison (1973) (ISBN: 0874512018) ed Marvin Meyers, 440pp

- James M. Smith, ed. The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776-1826. (3 vols. 1995).

- Jacob E. Cooke, ed. The Federalist. (1961)

- Madison, James. Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787.

- Madison, James. Letters & Other Writings Of James Madison Fourth President Of The United States Edited by William C. Rives & Philip R. Fendall, 4v (1865); called the Congress edition

- William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (1962-), the definitive multivolume edition, 29 volumes have been published, with 16+ more volumes planned.

- Gaillard Hunt, ed., The Writings of James Madison (9 vols 1900- 1910).

Secondary sources

Biographies

- Irving Brant, James Madison (6 vols., 1941-1961), the standard academic biography

- Ralph Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography (1971)

- Jack Rakove, James Madison and the Creation of the American Republic (2nd Edition 2001).

- Robert A. Rutland (editor); James Madison and the American Nation, 1751-1836: An Encyclopedia (1995) (ISBN 0-13-508425-3)

- Garry Wills, James Madison (2002), short

Analytic studies

- Banning, Lance. The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Creation of the Federal Republic, 1780-1792 (1995) online at ACLS History e-Book

- Gibson, Alan. "Lance Banning's Interpretation of James Madison: an Appreciation and Critique."Political Science Reviewer 2003 32: 269-317. Issn: 0091-3715 Fulltext online at Ebsco. Banning argues that, contrary to prevailing thought, James Madison remained committed to his revolutionary principles throughout his career. Some of Banning's claims are problematic, including his contention that Madison consistently supported peoples' active political participation. His careful study of Madison, however, reveals the complexity of the founder's thought, something that makes it difficult for either the left or the right in American politics to fully claim him two centuries later.

- Channing, Edward. The Jeffersonian System: 1801-1811 (1906) political survey

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism (1995) most detailed analysis of politics of 1790s

- McCoy, Drew R. The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America (1980)m, economic issues

- McCoy, Drew R. The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy (1989), JM after 1816.

- Marshall Smelser. The Democratic Republic 1801-1815 (1968). political survey of the era

- Muñoz, Vincent Phillip. "James Madison's Principle of Religious Liberty" in "American Political Science Review" (2003) 97(1):17-32 online

- Rutland, Robert A. The Presidency of James Madison (1990), scholarly overview of his two terms

- Sheehan, Colleen. "Madison v. Hamilton: The Battle Over Republicanism and the Role of Public Opinion" American Political Science Review 2004 98(3): 405-424.

- Stagg, John C. A. Mr. Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American republic, 1783-1830. (1983).

- Paul A. Varg; Foreign Policies of the Founding Fathers. 1963.

- Wood, Gordon, "Is There a 'James Madison Problem'?" in Wood, Revolutionary characters (2006) pp 141-72.

External links

- James Madison Biography and Fact File

- Quotations by James Madison at Liberty-Tree.ca

- The James Madison Papers, 1723-1836 from the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, approximately 12,000 items captured in some 72,000 digital images.

- The Papers of James Madison from the Avalon Project

- Madison's last will and testament, 1835

- A history of the Madison family since the 17th century

- Official White House page for James Madison

- Madison Archives

- Works by James Madison at Project Gutenberg

- James Madison Museum

- Montpelier-Home of James Madison

- James Madison and the Social Utility of Religion: Risks vs. Rewards, James Hutson, Library of Congress

- Yahooligans!, James Madison

| Preceded by(none) | U.S. At-Large Congressman from Virginia 1789 – 1791 |

Succeeded by(district system) |

| Preceded by(at-large system) | U.S. Congressman for the 5th District of Virginia 1791 – 1793 |

Succeeded byGeorge Hancock |

| Preceded by(none) | U.S. Congressman for the 15th District of Virginia 1793 – 1797 |

Succeeded by(none) |

| Preceded byJohn Marshall | United States Secretary of State May 2, 1801 – March 4, 1809 |

Succeeded byRobert Smith |

| Preceded byThomas Jefferson | Democratic-Republican Party presidential candidate 1808 (won), 1812 (won) |

Succeeded byJames Monroe |

| Preceded byThomas Jefferson | President of the United States March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817 |

Succeeded byJames Monroe |

| The Federalist Papers | |

|---|---|

| Authors | |

| Papers | |

| Related | |

- 1751 births

- 1836 deaths

- American Episcopalians

- American slaveholders

- Continental Congressmen

- Federalist Papers

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia

- People from Virginia

- Presidents of the United States

- Signers of the United States Constitution

- United States presidential candidates

- United States Secretaries of State

- University of Virginia

- War of 1812 people

- History of the United States (1789–1849)