This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Os943 (talk | contribs) at 19:53, 24 August 2018 (→Morality: less quantity, more quality pls.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:53, 24 August 2018 by Os943 (talk | contribs) (→Morality: less quantity, more quality pls.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Opposition to Islam" redirects here. For other uses, see Anti-Islam (disambiguation).| This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. Please help summarize the quotations. Consider transferring direct quotations to Wikiquote or excerpts to Wikisource. (November 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Beliefs |

| Practices |

| History |

| Culture and society |

| Related topics |

| This article is of a series on |

| Criticism of religion |

|---|

| By religion |

| By religious figure |

| By text |

| Religious violence |

| Bibliographies |

| Related topics |

Criticism of Islam has existed since its formative stages. Early written disapproval came from Christians, before the ninth century, many of whom viewed Islam as a radical Christian heresy, as well as by some former Muslim atheists/agnostics such as Ibn al-Rawandi. After the September 11 attacks and other terrorist attacks in the early 21st century, hatred of Islam grew alongside criticism of it.

Objects of criticism include the morality and authenticity of the Quran and the Hadiths, along with the life of Muhammad, both in his public and personal life. Other criticism concerns many aspects of human rights in the Islamic world (in both historical and present-day societies), including the treatment of women, LGBT groups, and religious and ethnic minorities in Islamic law and practice. In the recent adoption of multiculturalism, some have questioned Islam's influence on the ability or willingness of Muslim citizens and immigrants to assimilate into Western countries. The issues when debating and questioning Islam are incredibly complex with each side having a different view on the morality, meaning, interpretation, and authenticity of each topic.

Truthfulness of Islam and Islamic scriptures

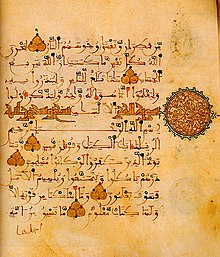

Reliability of the Quran

Originality of Quranic manuscripts. According to traditional Islamic scholarship, all of the Quran was written down by Muhammad's companions while he was alive (during 610–632 CE), but it was primarily an orally related document. The written compilation of the whole Quran in its definite form as we have it now was completed around 20 years after the death of Mohammed. John Wansbrough, Patricia Crone and Yehuda D. Nevo argue that all the primary sources which exist are from 150–300 years after the events which they describe, and thus are chronologically far removed from those events.

Imperfections in the Quran. Critics reject the idea that the Quran is miraculously perfect and impossible to imitate as asserted in the Quran itself. The 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, for example, writes: "The language of the Koran is held by the Mohammedans to be a peerless model of perfection. Critics, however, argue that peculiarities can be found in the text. For example, critics note that a sentence in which something is said concerning Allah is sometimes followed immediately by another in which Allah is the speaker (examples of this are suras xvi. 81, xxvii. 61, xxxi. 9, and xliii. 10.) Many peculiarities in the positions of words are due to the necessities of rhyme (lxix. 31, lxxiv. 3), while the use of many rare words and new forms may be traced to the same cause (comp. especially xix. 8, 9, 11, 16)." More serious are factual inaccuracies. For instance, Sura 25.53 claims that fresh water and salt water do not mix. While there may be cases in which these two bodies of water mix only slowly, every (fresh water) river that reaches an ocean will mix with salt water. Such areas of mixing are called estuaries (e.g. at the mouth of the Río de la Plata).

Judaism and the Quran. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, "The dependence of Mohammed upon his Jewish teachers or upon what he heard of the Jewish Haggadah and Jewish practices is now generally conceded." John Wansbrough believes that the Quran is a redaction in part of other sacred scriptures, in particular the Judaeo-Christian scriptures. Herbert Berg writes that "Despite John Wansbrough's very cautious and careful inclusion of qualifications such as "conjectural," and "tentative and emphatically provisional", his work is condemned by some. Some of this negative reaction is undoubtedly due to its radicalness...Wansbrough's work has been embraced wholeheartedly by few and has been employed in a piecemeal fashion by many. Many praise his insights and methods, if not all of his conclusions." Early jurists and theologians of Islam mentioned some Jewish influence but they also say where it is seen and recognized as such, it is perceived as a debasement or a dilution of the authentic message. Bernard Lewis describes this as "something like what in Christian history was called a Judaizing heresy." According to Moshe Sharon, the story of Muhammad having Jewish teachers is a legend developed in the 10th century CE. Philip Schaff described the Quran as having "many passages of poetic beauty, religious fervor, and wise counsel, but mixed with absurdities, bombast, unmeaning images, low sensuality."

Mohammed and God as speakers. According to Ibn Warraq, the Persian rationalist, Ali Dashti criticized the Quran on the basis that for some passages, "the speaker cannot have been God." Warraq gives Surah Al-Fatiha as an example of a passage which is "clearly addressed to God, in the form of a prayer." He says that by only adding the word "say" in front of the passage, this difficulty could have been removed. Furthermore, it is also known that one of the companions of Muhammad, Ibn Masud, rejected Surah Fatihah as being part of the Quran; these kind of disagreements are, in fact, common among the companions of Muhammad who could not decide which surahs were part of the Quran and which not.

Other criticism:

- The Quran contains verses which are difficult to understand or are perceived contradictory.

- There is a story that Shaytan tricked Mohammed into praising the idols of the Quraysh known as the Satanic Verses. However the account is incredibly weak and there is no saheeh source which suggests this claim to be true.

- Some accounts of the history of Islam say there were two verses of the Quran that were allegedly added by Muhammad when he was tricked by Satan (in an incident known as the "Story of the Cranes", later referred to as the "Satanic Verses"). These verses were then retracted at angel Gabriel's behest.

- The author of the Apology of al-Kindy Abd al-Masih ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (not to be confused with the famed philosopher al-Kindi) claimed that the narratives in the Quran were "all jumbled together and intermingled" and that this was "an evidence that many different hands have been at work therein, and caused discrepancies, adding or cutting out whatever they liked or disliked".

- The companions of Muhammad could not agree on which surahs were part of the Quran and which not. Two of the most famous companions being Ibn Masud and Ubay ibn Ka'b.

Reliability of the Hadith

Main article: Criticism of Hadith

Hadith are Muslim traditions relating to the Sunnah (words and deeds) of Muhammad. They are drawn from the writings of scholars writing between 844 and 874 CE, more than 200 years after the death of Mohammed in 632 CE. Within Islam, different schools, branches and sects have different opinions on the proper selection and use of Hadith. The four schools of Sunni Islam all consider Hadith second only to the Quran, although they differ on how much freedom of interpretation should be allowed to legal scholars. Shi'i scholars disagree with Sunni scholars as to which Hadith should be considered reliable. The Shi'as accept the Sunnah of Ali and the Imams as authoritative in addition to the Sunnah of Muhammad, and as a consequence they maintain their own, different, collections of Hadith.

It has been suggested that there exists around the Hadith three major sources of corruption: political conflicts, sectarian prejudice, and the desire to translate the underlying meaning, rather than the original words verbatim.

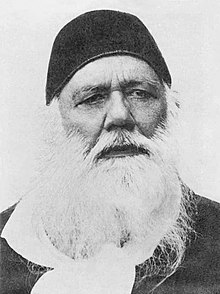

Muslim critics of the hadith, Quranists, reject the authority of hadith on theological grounds, pointing to verses in the Quran itself: "Nothing have We omitted from the Book", declaring that all necessary instruction can be found within the Quran, without reference to the Hadith. They claim that following the Hadith has led to people straying from the original purpose of God's revelation to Muhammad, adherence to the Quran alone. Ghulam Ahmed Pervez (1903–1985) was a noted critic of the Hadith and believed that the Quran alone was all that was necessary to discern God's will and our obligations. A fatwa, ruling, signed by more than a thousand orthodox clerics, denounced him as a 'kafir', a non-believer. His seminal work, Maqam-e Hadith argued that the Hadith were composed of "the garbled words of previous centuries", but suggests that he is not against the idea of collected sayings of the Prophet, only that he would consider any hadith that goes against the teachings of Quran to have been falsely attributed to the Prophet. The 1986 Malaysian book "Hadith: A Re-evaluation" by Kassim Ahmad was met with controversy and some scholars declared him an apostate from Islam for suggesting that ""the hadith are sectarian, anti-science, anti-reason and anti-women."

John Esposito notes that "Modern Western scholarship has seriously questioned the historicity and authenticity of the hadith", maintaining that "the bulk of traditions attributed to the Prophet Muhammad were actually written much later." He mentions Joseph Schacht, considered the father of the revisionist movement, as one scholar who argues this, claiming that Schacht "found no evidence of legal traditions before 722," from which Schacht concluded that "the Sunna of the Prophet is not the words and deeds of the Prophet, but apocryphal material" dating from later. Other scholars, however, such as Wilferd Madelung, have argued that "wholesale rejection as late fiction is unjustified".

Orthodox Muslims do not deny the existence of false hadith, but believe that through the scholars' work, these false hadith have been largely eliminated.

Lack of secondary evidence

The traditional view of Islam has also been criticised for the lack of supporting evidence consistent with that view, such as the lack of archaeological evidence, and discrepancies with non-Muslim literary sources. In the 1970s, what has been described as a "wave of sceptical scholars" challenged a great deal of the received wisdom in Islamic studies. They argued that the Islamic historical tradition had been greatly corrupted in transmission. They tried to correct or reconstruct the early history of Islam from other, presumably more reliable, sources such as coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic sources. The oldest of this group was John Wansbrough (1928–2002). Wansbrough's works were widely noted, but perhaps not widely read. In 1972 a cache of ancient Qurans in a mosque in Sana'a, Yemen was discovered – commonly known as the Sana'a manuscripts. The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to early part of the 8th century. Puin has not published the entirety of his work, but noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography. He also suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.

Morality

Main article: Morality in IslamMuhammad

{{Main|Criticism of Muhammad}

mohammed have been immoral in many accounts. He married a little girl by the name of Aisha, which he had never from. he waged war against people that threatened the sake of his comrades, thus he is not moral

Women in Islam

Main article: Women in IslamDomestic violence

Main article: Islam and domestic violenceThe relationship between Islam and domestic violence is heavily disputed. Even among Muslims, the uses and interpretations of sharia, the moral code and religious law of Islam, lack consensus.

One notable verse in the topic is 4:34, which states "As to those women from whom you fear disobedience, first admonish them, then refuse to share your bed with them, and then, if necessary, beat them." Nearly all scholars agree that it allows a husband to hit his wife, but in a way that does not cause physical pain, whilst others claim it only supports separating from ones wife. Due to the way domestic violence is handled in some modern-day Muslim states, a few organizations have suggested ways to modify Shari'a-inspired laws to improve women's rights in Islamic n ations, including women's rights in domestic abuse cases.

Personal status laws and child marriage

Shari'a is the basis for personal status laws in most Islamic majority nations. These personal status laws determine rights of women in matters of marriage, divorce and child custody. A 2011 UNICEF report concludes that Shari'a law provisions are discriminatory against women from a human rights perspective. In legal proceedings under Shari'a law, a woman's testimony is worth half of a man's before a court.

Except for Iran, Lebanon and Bahrain which allow child marriages, the civil code in Islamic majority countries do not allow child marriage of girls. However, with Shari'a personal status laws, Shari'a courts in all these nations have the power to override the civil code. The religious courts permit girls less than 18 years old to marry. As of 2011, child marriages are common in a few Middle Eastern countries, accounting for 1 in 6 all marriages in Egypt and 1 in 3 marriages in Yemen. However, the average age at marriage in most Middle Eastern countries is steadily rising and is generally in the low to mid 20s for women. Rape is considered a crime in all countries, but Shari'a courts in Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Syria and Tunisia in some cases allow a rapist to escape punishment by marrying his victim, while in other cases the victim who complains is often prosecuted with the crime of Zina (adultery).

Women's right to property and consent

Sharia grants women the right to inherit property from other family members, and these rights are detailed in the Quran. A woman's inheritance is unequal and less than a man's, and dependent on many factors. For instance, a daughter's inheritance is usually half that of her brother's.

Islamic law grants Muslim women many legal rights, such as the right to own property received as mahr (brideprice) at her marriage, that Western legal systems did not grant to women, according to Jamal Badawi. However, Islamic law does not grant non-Muslim women the same legal rights. Sharia recognizes the basic inequality between master and women slave, between free women and slave women, between believers and non-believers, as well as their unequal rights. Sharia authorized the institution of slavery, using the words abd (slave) and the phrase ma malakat aymanukum ("that which your right hand owns") to refer to women slaves, seized as captives of war. Under Islamic law, Muslim men could have sexual relations with female captives and slaves without her consent.

Slave women under sharia did not have a right to own property, right to free movement or right to consent. Sharia, in Islam's history, provided religious foundation for enslaving non-Muslim women (and men), as well as encouraged slave's manumission. However, manumission required that the non-Muslim slave first convert to Islam. Non-Muslim slave women who bore children to their Muslim masters became legally free upon her master's death, and her children were presumed to be Muslims as their father, in Africa, and elsewhere.

Starting with the 20th century, Western legal systems evolved to expand women's rights, but women's rights under Islamic law have remained tied to Quran, hadiths and their faithful interpretation as sharia by Islamic jurists.

Criticism of Muslim immigrants and immigration

See also: Multiculturalism and Islam

The immigration of Muslims to Europe has increased in recent decades and conservative Muslim social attitudes on modern issues have caused controversy in Europe and other parts of the world. Scholars argue about how much these attitudes are a result of culture rather than Islamic beliefs, whilst some critics consider Islam to be incompatible with secular Western society. Some also believe that Islam positively commands its adherents to impose its religious law on all peoples, believers and unbelievers alike, whenever possible and by any means necessary. Their criticism has been partly influenced by a stance against multiculturalism advocated by recent philosophers, closely linked to the heritage of New Philosophers. Statements by proponents like Pascal Bruckner describe multiculturalism as an invention of an "enlightened" elite who deny the benefits of democratic rights to non-Westerners by chaining them to their roots. They also state that multiculturalism allows a degree of religious freedom that exceeds what is needed for personal religious freedom and is conducive to the creation of organizations aimed at undermining European secular or Christian values.

Comparison with communism and fascist ideologies

In 2004, speaking to the Acton Institute on the problems of "secular democracy", Cardinal George Pell drew a parallel between Islam and communism: "Islam may provide in the 21st century, the attraction that communism provided in the 20th, both for those that are alienated and embittered on the one hand and for those who seek order or justice on the other." Pell also agrees in another speech that its capacity for far-reaching renovation is severely limited. An Australian Islamist spokesman, Keysar Trad, responded to the criticism: "Communism is a godless system, a system that in fact persecutes faith". Geert Wilders, a controversial Dutch member of parliament and leader of the Party for Freedom, has also compared Islam to fascism and communism.

- Islamism

Writers such as Stephen Suleyman Schwartz and Christopher Hitchens, find some elements of Islamism fascistic. Malise Ruthven, a Scottish writer and historian who writes on religion and Islamic affairs, opposes redefining Islamism as "Islamofascism", but also finds the resemblances between the two ideologies "compelling".

French philosopher Alexandre del Valle compared Islamism with fascism and communism in his Red-green-brown alliance theory.

Raymond Leo Burke, a Cardinal-Deacon of the Catholic Church has stated that Islam is not a religion but a totalitarian political system with religious elements which is dedicated to the conquest of the whole world.

Responses to criticism

John Esposito has written a number of introductory texts on Islam and the Islamic world. He has addressed issues including the rise of militant Islam, the veiling of women, and democracy. Esposito emphatically argues against what he calls the "pan-Islamic myth". He thinks that "too often coverage of Islam and the Muslim world assumes the existence of a monolithic Islam in which all Muslims are the same." To him, such a view is naive and unjustifiably obscures important divisions and differences in the Muslim world.

William Montgomery Watt in his book Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman addresses Muhammad's alleged moral failings. Watt argues on a basis of moral relativism that Muhammad should be judged by the standards of his own time and country rather than "by those of the most enlightened opinion in the West today."

Karen Armstrong, tracing what she believes to be the West's long history of hostility toward Islam, finds in Muhammad's teachings a theology of peace and tolerance. Armstrong holds that the "holy war" urged by the Quran alludes to each Muslim's duty to fight for a just, decent society.

Edward Said, in his essay Islam Through Western Eyes, stated that the general basis of Orientalist thought forms a study structure in which Islam is placed in an inferior position as an object of study. He claims the existence of a very considerable bias in Orientalist writings as a consequence of the scholars' cultural make-up. He claims Islam has been looked at with a particular hostility and fear due to many obvious religious, psychological and political reasons, all deriving from a sense "that so far as the West is concerned, Islam represents not only a formidable competitor but also a late-coming challenge to Christianity."

Cathy Young of Reason Magazine claims that "criticism of the religion is enmeshed with cultural and ethnic hostility" often painting the Muslim world as monolithic. While stating that the terms "Islamophobia" and "anti-Muslim bigotry" are often used in response to legitimate criticism of fundamentalist Islam and problems within Muslim culture, she claimed "the real thing does exist, and it frequently takes the cover of anti-jihadism."

See also

Template:Misplaced Pages books

- Clarion Project

- Criticism of Twelver Shia Islam

- Faith Freedom International

- Fitna

- Innocence of Muslims

- Internet Infidels

- Islamic Circle of North America

- Islamic feminism

- Islamo-leftism

- Islam: What the West Needs to Know

- Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

- List of critics of Islam

- Muslims Condemn

- Shia–Sunni relations

- Sudanese teddy bear blasphemy case

- The Satanic Verses controversy

- Trial of Geert Wilders

Notes

- De Haeresibus by John of Damascus. See Migne. Patrologia Graeca, vol. 94, 1864, cols 763–73. An English translation by the Reverend John W Voorhis appeared in The Moslem World, October 1954, pp. 392–98.

- Akyol, Mustafa (13 January 2015). "Islam's Problem With Blasphemy". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Bible in Mohammedian Literature., by Kaufmann Kohler Duncan B. McDonald, Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- Mohammed and Mohammedanism, by Gabriel Oussani, Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 16, 2006.

- Ibn Warraq, The Quest for Historical Muhammad (Amherst, Mass.:Prometheus, 2000), 103.

- "Saudi Arabia".

- Timothy Garton Ash (2006-10-05). "Islam in Europe". The New York Review of Books.

- Tariq Modood (2006-04-06). Multiculturalism, Muslims and Citizenship: A European Approach (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-0415355155.

- Leaman, Oliver (2006). "Canon". The Qur'an: an Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 136–39. ISBN 0415326397.

- Yehuda D. Nevo "Towards a Prehistory of Islam," Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, vol.17, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1994 p. 108.

- John Wansbrough The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1978 p. 119

- Patricia Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam, Princeton University Press, 1987 p. 204.

- See the verses Quran 2:2, Quran 17:88–89, Quran 29:47, Quran 28:49

- ^ "Koran". From the Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- Wansbrough, John (1977). Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation

- Wansbrough, John (1978). The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History.

- Berg, Herbert (2000). The development of exegesis in early Islam: the authenticity of Muslim literature from the formative period. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 0700712240.

- Jews of Islam, Bernard Lewis, p. 70: Google Preview

- Studies in Islamic History and Civilization, Moshe Sharon, p. 347: Google Preview

- Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). History of the Christian church. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 44 "The Koran, And The Bible"

- ^ Warraq. Why I am Not a Muslim. Prometheus Books. p. 106. ISBN 0879759844.

- ^ Lester, Toby (January 1999). "What is the Koran?". The Atlantic.

- ""Satanic Verses"". islamqa.info. Archived from the original on 2018-07-09. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - Watt, W. Montgomery (1961). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-19-881078-4.

- "The Life of Muhammad", Ibn Ishaq, A. Guillaume (translator), 2002, p. 166 ISBN 0-19-636033-1

- Quoted in A. Rippin, Muslims: their religious beliefs and practices: Volume 1, London, 1991, p. 26

- Warraq, Ibn. The Origins of the Koran. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1573921985.

- An Atheist's Guide to Mohammedanism by Frank Zindler

- Goddard, Hugh; Helen K. Bond (Ed.), Seth Daniel Kunin (Ed.), Francesca Aran Murphy (Ed.) (2003). Religious Studies and Theology: An Introduction. New York University Press. p. 204. ISBN 0814799140.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 0195112342.

- Brown, Daniel W. "Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought", 1999. pp. 113, 134

- Quran, Chapter 6. The Cattle: 38

- Donmez, Amber C. "The Difference Between Quran-Based Islam and Hadith-Based Islam"

- Ahmad, Aziz. "Islamic Modernism in India and Pakistan, 1857–1964". London: Oxford University Press.

- Pervez, Ghulam Ahmed. Maqam-e Hadith Archived 2011-11-13 at the Wayback Machine, Urdu version Archived 2011-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Latif, Abu Ruqayyah Farasat. The Quraniyun of the Twentieth Century, Masters Assertion, September 2006

- Ahmad, Kassim. "Hadith: A Re-evaluation", 1986. English translation 1997

- Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0195112342.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. p. xi. ISBN 0521646960.

- By Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza, "Shi'ism", 1988. p. 35.

- "What do we actually know about Mohammed?". openDemocracy.

- ^ Donner, Fred Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing, Darwin Press, 1998

- "Surah 4:34 (An-Nisaa), Alim — Translated by Mohammad Asad, Gibraltar (1980)".

- "Hitting one's wife?". islamqa.info. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- "CEDAW and Muslim Family Laws, Sisters in Islam, Malaysia" (PDF). musawah.org. 2011.

- Brandt, Michele, and Jeffrey A. Kaplan. "The Tension between Women's Rights and Religious Rights: Reservations to Cedaw by Egypt, Bangladesh and Tunisia." Journal of Law and Religion 12.1 (1995): 105–42.

- "Lebanon – IRIN, United Nations Office of Humanitarian Affairs (2009)". IRINnews.

- "UAE: Spousal Abuse never a Right". Human Rights Watch. 2010.

- ^ "MENA Gender Equality Profile – Status of Girls and Women in the Middle East and North Africa" (PDF). unicef.org. October 2011.

- "Age at First Marriage – Female By Country – Data from Quandl". Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Heideman, Kendra; Youssef, Mona. "Challenges to Women's Security in the MENA Region, Wilson Center (March, 2013)" (PDF). reliefweb.int.

- "Sanja Kelly (2010) New Survey Assesses Women's Freedom in the Middle East". Freedom House (funded by US Department of State's Middle East Partnership Initiative).

- Horrie, Chris; Chippindale, Peter (1991). p. 49.

- ^ David Powers (1993), "Islamic Inheritance System: A Socio-Historical Approach", The Arab Law Quarterly, 8, p. 13

- Feldman, Noah (March 16, 2008). "Why Shariah?". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- Dr. Badawi, Jamal A. (September 1971). "The Status of Women in Islam". Al-Ittihad Journal of Islamic Studies. 8 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^

- Bernard Lewis (2002), What Went Wrong?, ISBN 0195144201, pp. 82–83;

- Brunschvig. 'Abd; Encyclopedia of Islam, Brill, 2nd Edition, Vol 1, pp. 13-40.

- Slavery in Islam BBC Religions Archives

- Mazrui, A.A. (1997). "Islamic and Western values". Foreign Affairs, pp. 118–32.

- ^ Ali, K. (2010). Marriage and slavery in early Islam. Harvard University Press.

- Sikainga, Ahmad A. (1996). Slaves Into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292776942.

- Tucker, Judith E.; Nashat, Guity (1999). Women in the Middle East and North Africa. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253212642.

- ^ Lovejoy, Paul (2000). Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0521784306.

Quote: The religious requirement that new slaves be pagans and need for continued imports to maintain slave population made Africa an important source of slaves for the Islamic world. (...) In Islamic tradition, slavery was perceived as a means of converting non-Muslims. One task of the master was religious instruction and theoretically Muslims could not be enslaved. Conversion (of a non-Muslim to Islam) did not automatically lead to emancipation, but assimilation into Muslim society was deemed a prerequisite for emancipation.

- Jean Pierre Angenot; et al. (2008). Uncovering the History of Africans in Asia. Brill Academic. p. 60. ISBN 978-9004162914.

Quote: Islam imposed upon the Muslim master an obligation to convert non-Muslim slaves and become members of the greater Muslim society. Indeed, the daily observation of well defined Islamic religious rituals was the outward manifestation of conversion without which emancipation was impossible.

- Kecia Ali; (Editor: Bernadette J. Brooten). Slavery and Sexual Ethics in Islam, in Beyond Slavery: Overcoming Its Religious and Sexual Legacies. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 107–19 . ISBN 978-0230100169.

The slave who bore her master's child became known in Arabic as an "umm walad"; she could not be sold, and she was automatically freed upon her master's death.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - Hafez, Mohammed (September 2006). "Why Muslims Rebel". Al-Ittihad Journal of Islamic Studies. 1 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Tariq Modood (2006). Multiculturalism, Muslims and Citizenship: A European Approach (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 3, 29, 46. ISBN 978-0415355155.

- Kilpatrick, William (2016). The Politically Incorrect Guide to Jihad. Regnery. p. 256. ISBN 978-1621575771.

- Pascal Bruckner – Enlightenment fundamentalism or racism of the anti-racists? appeared originally in German in the online magazine Perlentaucher on January 24, 2007.

- Pascal Bruckner – A reply to Ian Buruma and Timothy Garton Ash: "At the heart of the issue is the fact that in certain countries Islam is becoming Europe's second religion. As such, its adherents are entitled to freedom of religion, to decent locations and to all of our respect. On the condition, that is, that they themselves respect the rules of our republican, secular culture, and that they do not demand a status of extraterritoriality that is denied other religions, or claim special rights and prerogatives"

- Pascal Bruckner – A reply to Ian Buruma and Timothy Garton Ash "It's so true that many English, Dutch and German politicians, shocked by the excesses that the wearing of the Islamic veil has given way to, now envisage similar legislation curbing religious symbols in public space. The separation of the spiritual and corporeal domains must be strictly maintained, and belief must confine itself to the private realm."

- Nazir-Ali, Michael (6 January 2008). "Extremism flourished as UK lost Christianity". London: The Sunday Telegraph.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - George Pell (2004-10-12). "Is there only secular democracy? Imagining other possibilities for the third millennium". Archived from the original on 2006-02-08. Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- George Pell (2006-02-04). "Islam and Western Democracies". Archived from the original on June 5, 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-05.

- Toni Hassan (2004-11-12). "Islam is the new communism: Pell". Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- "Geert Wilders: Man Out of Time".

- Schwartz, Stephen. "What Is 'Islamofascism'?". TCS Daily. Archived from the original on 2006-09-24. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Hitchens, Christopher: Defending Islamofascism: It's a valid term. Here's why, Slate, 2007-10-22

- A Fury For God, Malise Ruthven, Granta, 2002, pp. 207–08

- Alexandre del Valle. "The Reds, The Browns and the Greens". alexandredelvalle.com. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- "Islam Is Not a Religion". www.churchmilitant.com. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- Esposito, John L. (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195157133.

- Esposito, John L. (2003). Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195168860.

- Esposito, John L. (1999). The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality?. Oxford University Press. pp. 225–28. ISBN 0195130766.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1961). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 0198810784. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- Armstrong, Karen (1993). Muhammad: A Biography of the Prophet. HarperSanFrancisco. p. 165. ISBN 0062508865.

- Edward W. Said (2 January 1998). "Islam Through Western Eyes". The Nation.

- "The Jihad Against Muslims". Reason.com.

References

- Ali, Muhammad (1997). Muhammad the Prophet. Ahamadiyya Anjuman Ishaat Islam. ISBN 978-0913321072.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cohen, Mark R. (1995). Under Crescent and Cross. Princeton University Press; Reissue edition. ISBN 978-0691010823.

- Lockman, Zachary (2004). Contending Visions of the Middle East: The History and Politics of Orientalism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521629379.

- Rippin, Andrew (2001). Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415217811.

- Westerlund, David (2003). "Ahmed Deedat's Theology of Religion: Apologetics through Polemics". Journal of Religion in Africa. 33 (3): 263. doi:10.1163/157006603322663505.

Further reading

- Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide by Bat Ye'or

- Decline of Eastern Christianity: From Jihad to Dhimmitude by Bat Ye'or

- The Al Qaeda Connection: International Terrorism, Organized Crime, And the Coming Apocalypse by Paul L. Williams Prometheus Books, ISBN 1591023491 (2005)

- The Amazing Quran by Gary Miller

- An Autumn of War: What America Learned from September 11 and the War on Terrorism by Victor Davis Hanson Anchor Books, 2002. ISBN 1400031133 A collection of essays, mostly from National Review, covering events occurring between September 11, 2001 and January 2002

- Arabs and Israel – Conflict or Conciliation? by Sheikh Ahmed Hoosen Deedat

- Slavery in Islam, BBC, September 7, 2009

- Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam by Gilles Kepel

- The War for Muslim Minds by Gilles Kepel

- J. Tolan, Saracens; Islam in the Medieval European Imagination (2002)

- Esposito, John L. (1995). The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195102983.

- Halliday, Fred (2003). Islam and the Myth of Confrontation: Religion and Politics of the Middle East. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1860648681.

- Esposito, John L. (2003). Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195168860.

- Geisler, Norman L. (2002). Answering Islam: The Crescent in Light of the Cross. Baker Books. ISBN 0801064309.

- Ibn Warraq, Why I Am Not a Muslim (1995)

- —, Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out

- The Institute for the Study of Civil Society report – The ‘West’, Islam and Islamism

- Zwemer Islam, a Challenge to Faith (New York, 1907)

- Shoja-e-din Shafa, Rebirth (1995) (Persian Title: تولدى ديگر)

- Shoja-e-din Shafa, After 1400 Years (2000) (Persian Title: پس از 1400 سال)

External links

Media related to Criticism of Islam at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Criticism of Islam at Wikimedia Commons

| Islam topics | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outline of Islam | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Theology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||