This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Jytdog (talk | contribs) at 23:06, 20 September 2018 (letter to the editor; not a MEDRS source). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:06, 20 September 2018 by Jytdog (talk | contribs) (letter to the editor; not a MEDRS source)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Psychobiotics are probiotic or prebiotic substances which are intended to confer mental health benefits by assisting or causing colonisation of the gut with commensal bacteria. This is mediated by changes in the gut flora which modify brain function via the Gut–brain axis. The term was introduced in 2012 by Dinan et al. in their seminal paper Psychobiotics: a novel class of Psychotropic to refer to “a live organism that, when ingested in adequate amounts, produces a health benefit in patients suffering from psychiatric illness”. This definition was expanded to include prebiotic treatment by Sarkar et al. in 2016.

Types

In probiotic psychobiotics the bacteria most commonly used are Gram-positive bacteria such as the Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus families, as these do not contain pro-inflammatory Lipopolysaccharide chains, reducing the likelihood of an immunological response.

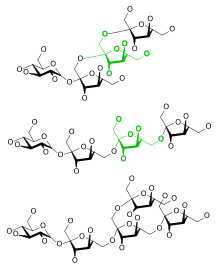

Prebiotic psychobiotics are substances such as fructans and oligosaccharides, which promote the growth of intrinsic commensal bacteria by their fermentation in the gut. Commensal fermentation also produces short-chain fatty acids which are important to gut physiology and play a role in the signalling between microbiota and the host.

A combination of a prebiotic and a probiotic is known as a synbiotic. Multiple bacterial species contained in a single probiotic broth is known as a polybiotic.

Proposed mechanisms of action

It has been observed that the gut microbiota of depressed patients differs from healthy individuals, and may be less diverse, and this has also been shown to hold true for animals which are subjected to models of depression. It is therefore thought that depression and gut microbiota phenotype are linked.

Further to this it has been found that depressive symptoms can be transmitted from animal to animal, and from human to animal by means of fecal microbiota transplant. It has been therefore speculated that microbiome composition may have a causative role in depression. Further to this, traditional antidepressant therapy may influence gut microbiota and this may play a role in their mechanism of action. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor drugs have been shown to inhibit the growth and spread of Gram-positive bacteria, tricyclic antidepressant drugs have a similar effect on the proliferation of Escherichia coli and Yersinia species, and ketamine may also inhibit growth of pathogenic bacteria.

It is thought that the microbiome influences the brain's activity by three pathways:

- Influencing the functioning of the Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis which has an impact on Neuroplasticity

- Interaction between the Enteric nervous system and the Vagus nerve decreasing or increasing neurogenesis

- Modulation of neuroinflammation by upregulation or downregulation of chronic inflammation in the gut.

Pathological changes in gut microbiotia may activate pro-inflammatory pathways via the NALP3 inflammasome which has been identified as a potential trigger for major depressive disorder.

The brain-gut axis and tryptophan metabolism have been linked. The brain cannot store tryptophan and requires a constant supply of this substance. Reduced peripheral tryptophan levels have been associated with depressive phenotype, and tryptophan levels and availability have been found to be directly influenced by the gut microbiota with Bifidobacteria being show to increase peripheral tryptophan. Bacteria play a role in serotonin synthesis from tryptophan in the gut Enterochromaffin cells and germ-free mice which are treated with probiotics show threefold increases in serotonin production.

Some intestinal microbes have been found to produce psychotropic effects by secreting neurotransmitter and neurotransmitter precursor molecules such as GABA, glycine and catecholamines, tyrosine, and also by regulating endocannabinoid receptor expression.

Commensal bacteria produce precursors of enzyme cofactors including Vitamin B12.

Research

It has been found that mice raised in a sterile environment demonstrate heightened physiological reactions to psychological stress compared to animals with a normal microbiome, and that these phenomena were reversible by promoting the formation of a healthy microbiome using probiotic treatment.

Psychobiotic treatment of mice exposed to a maternal deprivation model of anxiety and depression has been found to prevent the fall in physical performance and raised pro-inflammatory cytokine levels associated with untreated mice, and treatment of mice with Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotics has been found to reduce activation of the Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and colonic dysfunction in similar circumstances. These mice also expressed fewer depressive and anxious behaviours. In a similar maternal stress model the psychobiotic species Lactobacillus plantarum was able to reduce corticosterone markers of increased HPA axis activity in mice. A recent study found that psychobiotic lactobacillus broth treatment produced decreased levels of markers of oxidative stress, serotonin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the amygdala of diabetic rats, as well as lower indicators of anxiety and depression.

Some studies have found prebiotic treatment with galactooligosaccharides and fructooligosaccharides influences changes in short chain fatty acid production and improves populations of Akkermansia bacteria implicated in improved metabolic health in mice and potentially improved mental health, although more translational studies are required to determine whether this effect occurs in humans. Bimuno-GOS and FOS prebiotic supplementation has been found to have neuroprotective activity in animal models, and to raise BDNF levels in the hippocampus.

SFCAs such as butyrate, acetate and propionate are produced in increased amounts following administration of prebiotics. Butyrate has been demonstrated to have antidepressant effects, can cross the Blood–brain barrier, and has neuroprotective activity. This is thought to be mediated via its role as an epigenetic modulator, acting as a Histone deacetylase inhibitor. SCFAs also affect the local gut mucosal immune system, a potential mechanism by which modulation of the HPA axis may occur.

Bifidobacterium breve has been shown to alter the composition of brain fatty acids and lipids, which can lead to alterations in neurone sensitivity and transmission.

It has been proposed that high fat diets disrupt the gut microbiome in obese individuals, producing neuroinflammation and neurological disorders. Anthocyanin flavonoid compounds have been found to have a neuroprotective effect in obesity, which may be explained by their psychobiotic influence on the gut microbiome, and subsequently the gut-brain axis.

An association between adopting a Mediterranean diet and a reduction in depression has been well established, with even moderate adherence reducing depression risk, whilst more "western", high-fat, sugar diets are associated with higher reported anxiety and depression in women. It has been suggested that microbiota analysis of those on Mediterranean diets may help identify bacterial strains with potental psychobiotic activity.

L. Plantarum strain C29 has been reported to protect against memory deficits caused by Hyoscine and D-galactose, and ageing, and increased BDNF levels were observed in these studies also, a neuropeptide reduced in neurodegenerative disease.

Breast-fed infants have a different microbiome to formula-fed babies which may be responsible for their improved health outcomes. Damage to gut microbiota in early life may impact neurodevelopment leading to adverse mental health in later life.

Several human studies have found probiotics to have a beneficial effect on psychological coping mechanisms, overall mood, depression, anxiety, and stress. Additionally fMRI studies have shown changes in the activation of the midbrain after probiotic treatment, an area of the brain associated with processing emotional and sensory information.

However several systematic reviews have found insufficient evidence for the efficacy of probiotics in mental health applications, citing the need for more studies. Not all probiotics are the same, and most that have been studied do not have psychobiotic activity.

Species

Several species of bacteria have been used in probiotic psychobiotic preparations:

- Lactobacillus helveticus

- Bifidobacterium longum

- Lactobacillus casei

- Lactobacillus plantarum

- Lactobacillus acidophilus

- Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus

- Bifidobacterium breve

- Bifidobacterium infantis

- Streptococcus salivarius

See also

- Probiotic

- Gut–brain axis

- Gut flora

- Synbiotics

- Prebiotic (nutrition)

- Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

References

- ^ Sarkar A, Lehto SM, Harty S, Dinan TG, Cryan JF, Burnet PW (November 2016). "Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria-Gut-Brain Signals". Trends in Neurosciences. 39 (11): 763–781. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002. PMC 5102282. PMID 27793434.

- ^ Dinan TG, Stanton C, Cryan JF (November 2013). "Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic". Biological Psychiatry. 74 (10): 720–6. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001. PMID 23759244.

- ^ Foster JA (October 2017). "Targeting the Microbiome for Mental Health: Hype or Hope?". Biological Psychiatry. 82 (7): 456–457. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.002. PMID 28870296.

- ^ Bambury A, Sandhu K, Cryan JF, Dinan TG (December 2017). "Finding the needle in the haystack: systematic identification of psychobiotics". British Journal of Pharmacology. doi:10.1111/bph.14127. PMID 29243233.

- ^ Liang S, Wu X, Hu X, Wang T, Jin F (May 2018). "Recognizing Depression from the Microbiota⁻Gut⁻Brain Axis". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 19 (6). doi:10.3390/ijms19061592. PMC 6032096. PMID 29843470.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kali A (June 2016). "Psychobiotics: An emerging probiotic in psychiatric practice". Biomedical Journal. 39 (3): 223–4. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2015.11.004. PMID 27621125.

- Inserra A, Rogers GB, Licinio J, Wong ML (September 2018). "The Microbiota-Inflammasome Hypothesis of Major Depression". BioEssays. 40 (9): e1800027. doi:10.1002/bies.201800027. PMID 30004130.

- ^ Tang F, Reddy BL, Saier MH (2014). "Psychobiotics and their involvement in mental health". Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 24 (4): 211–4. doi:10.1159/000366281. PMID 25196442.

- Wall R, Cryan JF, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Dinan TG, Stanton C (2014). "Bacterial neuroactive compounds produced by psychobiotics". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 817: 221–39. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_10. PMID 24997036.

- ^ Liu YW, Liong MT, Tsai YC (September 2018). "New perspectives of Lactobacillus plantarum as a probiotic: The gut-heart-brain axis". Journal of Microbiology. 56 (9): 601–613. doi:10.1007/s12275-018-8079-2. PMID 30141154.

- Morshedi M, Valenlia KB, Hosseinifard ES, Shahabi P, Abbasi MM, Ghorbani M, Barzegari A, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Saghafi-Asl M (July 2018). "Beneficial psychological effects of novel psychobiotics in diabetic rats: the interaction among the gut, blood and amygdala". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 57: 145–152. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.03.022. PMID 29730508.

- Marques C, Fernandes I, Meireles M, Faria A, Spencer JP, Mateus N, Calhau C (July 2018). "Gut microbiota modulation accounts for the neuroprotective properties of anthocyanins". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 11341. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-29744-5. PMC 6063953. PMID 30054537.

- Tanner G, Matthews K, Roeder H, Konopasek M, Bussard A, Gregory T (May 2018). "Current and future uses of probiotics". Jaapa. 31 (5): 29–33. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000532117.21250.0f. PMID 29698369.

- Romijn AR, Rucklidge JJ (October 2015). "Systematic review of evidence to support the theory of psychobiotics". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (10): 675–93. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv025. PMID 26370263.

- Liu B, He Y, Wang M, Liu J, Ju Y, Zhang Y, Liu T, Li L, Li Q (July 2018). "Efficacy of probiotics on anxiety-A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Depression and Anxiety. doi:10.1002/da.22811. PMID 29995348.