This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Jytdog (talk | contribs) at 00:29, 21 September 2018 (→Research: positive statement, rather than the negative.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:29, 21 September 2018 by Jytdog (talk | contribs) (→Research: positive statement, rather than the negative.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Psychobiotics are probiotic or prebiotic substances which are intended to confer mental health benefits by assisting or causing colonisation of the gut with commensal bacteria, which is hypothesized to modify brain function via the gut–brain axis.

Types

In probiotic psychobiotics the bacteria most commonly used are Gram-positive bacteria such as the Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus families, as these do not contain pro-inflammatory lipopolysaccharide chains, reducing the likelihood of an immunological response.

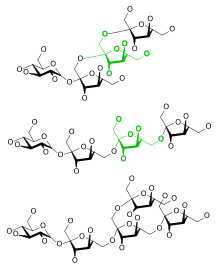

Prebiotic psychobiotics are substances such as fructans and oligosaccharides, which promote the growth of intrinsic commensal bacteria by their fermentation in the gut.

A combination of a prebiotic and a probiotic is known as a synbiotic. Multiple bacterial species contained in a single probiotic broth is known as a polybiotic.

Proposed mechanisms of action

Pathological changes in gut microbiotia may activate pro-inflammatory pathways via the NALP3 inflammasome which has been identified as a potential trigger for major depressive disorder.

The brain-gut axis and tryptophan metabolism have been linked. The brain cannot store tryptophan and requires a constant supply of this substance. Reduced peripheral tryptophan levels have been associated with depressive phenotype, and tryptophan levels and availability have been found to be directly influenced by the gut microbiota with Bifidobacteria being show to increase peripheral tryptophan. Bacteria play a role in serotonin synthesis from tryptophan in the gut Enterochromaffin cells and germ-free mice which are treated with probiotics show threefold increases in serotonin production.

Some intestinal microbes have been found to produce psychotropic effects by secreting neurotransmitter and neurotransmitter precursor molecules such as GABA, glycine, catecholamines and tyrosine, and also by regulating endocannabinoid receptor expression.

Research

As of 2018, there had been several clinical trials of psychobiotic; reviews of these trials concluded that there is no good evidence that psychobiotics are safe and effective in humans.

Preclinical studies in animal models such as rats and mice. Mice raised in a sterile environment demonstrate heightened physiological reactions to psychological stress compared to animals with a normal microbiome, and that these phenomena were reversible by promoting the formation of a healthy microbiome using probiotic treatment. Psychobiotic treatment of mice exposed to a maternal deprivation model of anxiety and depression has been found to prevent the fall in physical performance and raised pro-inflammatory cytokine levels associated with untreated mice, and treatment of mice with Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotics has been found to reduce activation of the Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and colonic dysfunction in similar circumstances. These mice also expressed fewer depressive and anxious behaviours. In a similar maternal stress model the psychobiotic species Lactobacillus plantarum was able to reduce corticosterone markers of increased HPA axis activity in mice.

Bimuno-GOS and FOS prebiotic supplementation has been found to have neuroprotective activity in animal models, and to raise BDNF levels in the hippocampus. Short chain fatty acids such as butyrate, acetate and propionate are produced in increased amounts following administration of prebiotics in animal models. Butyrate has been demonstrated to have antidepressant effects, can cross the Blood–brain barrier, and has neuroprotective activity. This is thought to be mediated via its role as an epigenetic modulator, acting as a Histone deacetylase inhibitor. SCFAs also affect the local gut mucosal immune system, a potential mechanism by which modulation of the HPA axis may occur.

There is a correlation between eating a Mediterranean diet over a long period of time and a reduced risk of major depressive disorder; a 2017 review suggested that microbiota analysis of people on such diets might identify bacterial strains with potential psychobiotic activity.

Species

Several species of bacteria have been used in probiotic psychobiotic preparations:

- Lactobacillus helveticus

- Bifidobacterium longum

- Lactobacillus casei

- Lactobacillus plantarum

- Lactobacillus acidophilus

- Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus

- Bifidobacterium breve

- Bifidobacterium infantis

- Streptococcus salivarius

References

- ^ Sarkar A, Lehto SM, Harty S, Dinan TG, Cryan JF, Burnet PW (November 2016). "Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria-Gut-Brain Signals". Trends in Neurosciences. 39 (11): 763–781. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002. PMC 5102282. PMID 27793434.

- ^ Bambury A, Sandhu K, Cryan JF, Dinan TG (December 2017). "Finding the needle in the haystack: systematic identification of psychobiotics". British Journal of Pharmacology. doi:10.1111/bph.14127. PMID 29243233.

- Inserra A, Rogers GB, Licinio J, Wong ML (September 2018). "The Microbiota-Inflammasome Hypothesis of Major Depression". BioEssays. 40 (9): e1800027. doi:10.1002/bies.201800027. PMID 30004130.

- Wall R, Cryan JF, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Dinan TG, Stanton C (2014). "Bacterial neuroactive compounds produced by psychobiotics". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 817: 221–39. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_10. PMID 24997036.

- Romijn AR, Rucklidge JJ (October 2015). "Systematic review of evidence to support the theory of psychobiotics". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (10): 675–93. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv025. PMID 26370263.

- Liu B, He Y, Wang M, Liu J, Ju Y, Zhang Y, Liu T, Li L, Li Q (July 2018). "Efficacy of probiotics on anxiety-A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Depression and Anxiety. doi:10.1002/da.22811. PMID 29995348.

- ^ Liu YW, Liong MT, Tsai YC (September 2018). "New perspectives of Lactobacillus plantarum as a probiotic: The gut-heart-brain axis". Journal of Microbiology. 56 (9): 601–613. doi:10.1007/s12275-018-8079-2. PMID 30141154.

- Psaltopoulou, T; Sergentanis, TN; Panagiotakos, DB; Sergentanis, IN; Kosti, R; Scarmeas, N (October 2013). "Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: A meta-analysis". Annals of neurology. 74 (4): 580–91. doi:10.1002/ana.23944. PMID 23720230.