This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Markygshadow (talk | contribs) at 14:10, 13 March 2019. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:10, 13 March 2019 by Markygshadow (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)/

///

Theological viewpoints

See also: Christian views on astrology, Jewish views on astrology, and Muslim views on astrologyAncient

St. Augustine (354–430) believed that the determinism of astrology conflicted with the Christian doctrines of man's free will and responsibility, and God not being the cause of evil, but he also grounded his opposition philosophically, citing the failure of astrology to explain twins who behave differently although conceived at the same moment and born at approximately the same time.

Medieval

Some of the practices of astrology were contested on theological grounds by medieval Muslim astronomers such as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) and Avicenna. They said that the methods of astrologers conflicted with orthodox religious views of Islamic scholars, by suggesting that the Will of God can be known and predicted in advance. For example, Avicenna's 'Refutation against astrology', Risāla fī ibṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm, argues against the practice of astrology while supporting the principle that planets may act as agents of divine causation. Avicenna considered that the movement of the planets influenced life on earth in a deterministic way, but argued against the possibility of determining the exact influence of the stars. Essentially, Avicenna did not deny the core dogma of astrology, but denied our ability to understand it to the extent that precise and fatalistic predictions could be made from it. Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya (1292–1350), in his Miftah Dar al-SaCadah, also used physical arguments in astronomy to question the practice of judicial astrology. He recognised that the stars are much larger than the planets, and argued:

And if you astrologers answer that it is precisely because of this distance and smallness that their influences are negligible, then why is it that you claim a great influence for the smallest heavenly body, Mercury? Why is it that you have given an influence to al-Ra's and al-Dhanab, which are two imaginary points ?

Maimonides, the preeminent Jewish philosopher, astronomer, and legal codifier, wrote that astrology is forbidden by Jewish law.

Modern

The Catechism of the Catholic Church maintains that divination, including predictive astrology, is incompatible with modern Catholic beliefs such as free will:

All forms of divination are to be rejected: recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to "unveil" the future. Consulting horoscopes, astrology, palm reading, interpretation of omens and lots, the phenomena of clairvoyance, and recourse to mediums all conceal a desire for power over time, history, and, in the last analysis, other human beings, as well as a wish to conciliate hidden powers. They contradict the honor, respect, and loving fear that we owe to God alone.

— Catechism of the Catholic Church

K

Cultural impact

Venus, the Bringer of Peace Venus, performed by the US Air Force Band

Mercury, the Winged Messenger Mercury, performed by the US Air Force Band

Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity Jupiter, performed by the US Air Force Band

Uranus, the Magician Uranus, performed by the US Air Force Band

Problems playing these files? See media help.

Western politics and society

In the West, political leaders have sometimes consulted astrologers. For example, the British intelligence agency MI5 employed Louis de Wohl as an astrologer after claims surfaced that Adolf Hitler used astrology to time his actions. The War Office was "...interested to know what Hitler's own astrologers would be telling him from week to week." In fact, de Wohl's predictions were so inaccurate that he was soon labelled a "complete charlatan," and later evidence showed that Hitler considered astrology "complete nonsense." After John Hinckley's attempted assassination of US President Ronald Reagan, first lady Nancy Reagan commissioned astrologer Joan Quigley to act as the secret White House astrologer. However, Quigley's role ended in 1988 when it became public through the memoirs of former chief of staff, Donald Regan.

There was a boom in interest in astrology in the late 1960s. The sociologist Marcello Truzzi described three levels of involvement of "Astrology-believers" to account for its revived popularity in the face of scientific discrediting. He found that most astrology-believers did not claim it was a scientific explanation with predictive power. Instead, those superficially involved, knowing "next to nothing" about astrology's 'mechanics', read newspaper astrology columns, and could benefit from "tension-management of anxieties" and "a cognitive belief-system that transcends science." Those at the second level usually had their horoscopes cast and sought advice and predictions. They were much younger than those at the first level, and could benefit from knowledge of the language of astrology and the resulting ability to belong to a coherent and exclusive group. Those at the third level were highly involved and usually cast horoscopes for themselves. Astrology provided this small minority of astrology-believers with a "meaningful view of their universe and them an understanding of their place in it." This third group took astrology seriously, possibly as a sacred canopy, whereas the other two groups took it playfully and irreverently.

In 1953, the sociologist Theodor W. Adorno conducted a study of the astrology column of a Los Angeles newspaper as part of a project examining mass culture in capitalist society. Adorno believed that popular astrology, as a device, invariably leads to statements that encouraged conformity—and that astrologers who go against conformity, by discouraging performance at work etc., risk losing their jobs. Adorno concluded that astrology is a large-scale manifestation of systematic irrationalism, where individuals are subtly led—through flattery and vague generalisations—to believe that the author of the column is addressing them directly. Adorno drew a parallel with the phrase opium of the people, by Karl Marx, by commenting, "occultism is the metaphysic of the dopes."

A 2005 Gallup poll and a 2009 survey by the Pew Research Center reported that 25% of US adults believe in astrology. According to data released in the National Science Foundation's 2014 Science and Engineering Indicators study, "Fewer Americans rejected astrology in 2012 than in recent years." The NSF study noted that in 2012, "slightly more than half of Americans said that astrology was 'not at all scientific,' whereas nearly two-thirds gave this response in 2010. The comparable percentage has not been this low since 1983."

India and Japan

In India, there is a long-established and widespread belief in astrology. It is commonly used for daily life, particularly in matters concerning marriage and career, and makes extensive use of electional, horary and karmic astrology. Indian politics have also been influenced by astrology. It is still considered a branch of the Vedanga. In 2001, Indian scientists and politicians debated and critiqued a proposal to use state money to fund research into astrology, resulting in permission for Indian universities to offer courses in Vedic astrology.

On February 2011, the Bombay High Court reaffirmed astrology's standing in India when it dismissed a case that challenged its status as a science.

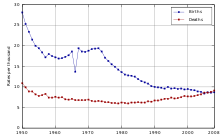

In Japan, strong belief in astrology has led to dramatic changes in the fertility rate and the number of abortions in the years of Fire Horse. Adherents believe that women born in hinoeuma years are unmarriageable and bring bad luck to their father or husband. In 1966, the number of babies born in Japan dropped by over 25% as parents tried to avoid the stigma of having a daughter born in the hinoeuma year.

Literature and music

The fourteenth-century English poets John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer both referred to astrology in their works, including Gower's Confessio Amantis and Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales. Chaucer commented explicitly on astrology in his Treatise on the Astrolabe, demonstrating personal knowledge of one area, judicial astrology, with an account of how to find the ascendant or rising sign.

In the fifteenth century, references to astrology, such as with similes, became "a matter of course" in English literature.

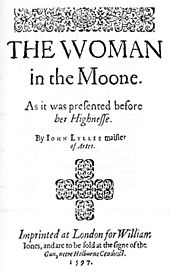

In the sixteenth century, John Lyly's 1597 play, The Woman in the Moon, is wholly motivated by astrology, while Christopher Marlowe makes astrological references in his plays Doctor Faustus and Tamburlaine (both c. 1590), and Sir Philip Sidney refers to astrology at least four times in his romance The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia (c. 1580). Edmund Spenser uses astrology both decoratively and causally in his poetry, revealing "...unmistakably an abiding interest in the art, an interest shared by a large number of his contemporaries." George Chapman's play, Byron's Conspiracy (1608), similarly uses astrology as a causal mechanism in the drama. William Shakespeare's attitude towards astrology is unclear, with contradictory references in plays including King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, and Richard II. Shakespeare was familiar with astrology and made use of his knowledge of astrology in nearly every play he wrote, assuming a basic familiarity with the subject in his commercial audience. Outside theatre, the physician and mystic Robert Fludd practised astrology, as did the quack doctor Simon Forman. In Elizabethan England, "The usual feeling about astrology ... that it is the most useful of the sciences."

In seventeenth century Spain, Lope de Vega, with a detailed knowledge of astronomy, wrote plays that ridicule astrology. In his pastoral romance La Arcadia (1598), it leads to absurdity; in his novela Guzman el Bravo (1624), he concludes that the stars were made for man, not man for the stars. Calderón de la Barca wrote the 1641 comedy Astrologo Fingido (The Pretended Astrologer); the plot was borrowed by the French playwright Thomas Corneille for his 1651 comedy Feint Astrologue.

The most famous piece of music influenced by astrology is the orchestral suite The Planets. Written by the British composer Gustav Holst (1874–1934), and first performed in 1918, the framework of The Planets is based upon the astrological symbolism of the planets. Each of the seven movements of the suite is based upon a different planet, though the movements are not in the order of the planets from the Sun. The composer Colin Matthews wrote an eighth movement entitled Pluto, the Renewer, first performed in 2000. In 1937, another British composer, Constant Lambert, wrote a ballet on astrological themes, called Horoscope. In 1974, the New Zealand composer Edwin Carr wrote The Twelve Signs: An Astrological Entertainment for orchestra without strings. Camille Paglia acknowledges astrology as an influence on her work of literary criticism Sexual Personae (1990).

Astrology features strongly in Eleanor Catton's The Luminaries, recipient of the 2013 Man Booker Prize.

See also

- Barnum effect

- List of astrological traditions, types, and systems

- List of topics characterised as pseudoscience

Notes

- Italics in original.

References

- Veenstra, J.R. (1997). Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France: Text and Context of Laurens Pignon's "Contre les Devineurs" (1411). Brill. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-90-04-10925-4.

- ^ Hess, Peter M.J.; Allen, Paul L. (2007). Catholicism and science (1st ed.). Westport: Greenwood. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-313-33190-9.

- Saliba, George (1994b). A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York University Press. pp. 60, 67–69. ISBN 978-0-8147-8023-7.

- Catarina Belo, Catarina Carriço Marques de Moura Belo, Chance and determinism in Avicenna and Averroës, p. 228. Brill, 2007. ISBN 90-04-15587-2.

- George Saliba, Avicenna: 'viii. Mathematics and Physical Sciences'. Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition, 2011, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/avicenna-viii

- ^ Livingston, John W. (1971). "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: A Fourteenth Century Defense against Astrological Divination and Alchemical Transmutation". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 91 (1): 96–103. doi:10.2307/600445. JSTOR 600445.

- Rambam Avodat Kochavim 11:9

- editor, Peter M.J. Stravinskas (1998). Our Sunday visitor's Catholic encyclopedia (Rev. ed.). Huntington, Ind.: Our Sunday Visitor Pub. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-87973-669-9.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "Catechism of the Catholic Church - Part 3". Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "The Strange Story Of Britain's "State Seer"". The Sydney Morning Herald. 30 August 1952. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Norton-Taylor, Richard (4 March 2008). "Star turn: astrologer who became SOE's secret weapon against Hitler". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Regan, Donald T. (1988). For the record: from Wall Street to Washington (first ed.). San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-163966-3.

- Quigley, Joan (1990). What does Joan say? : my seven years as White House astrologer to Nancy and Ronald Reagan. Secaucus, NJ: Birch Lane Press. ISBN 978-1-55972-032-8.

- Gorney, Cynthia (11 May 1988). "The Reagan Chart Watch; Astrologer Joan Quigley, Eye on the Cosmos". The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Truzzi, Marcello (1972). "The Occult Revival as Popular Culture: Some Random Observations on the Old and the Nouveau Witch". The Sociological Quarterly. 13 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1972.tb02101.x. JSTOR 4105818.

- ^ Cary J. Nederman; James Wray Goulding (Winter 1981). "Popular Occultism and Critical Social Theory: Exploring Some Themes in Adorno's Critique of Astrology and the Occult". Sociological Analysis. 42.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Theodor W. Adorno (Spring 1974). "The Stars Down to Earth: The Los Angeles Times Astrology Column". Telos. 1974 (19): 13–90. doi:10.3817/0374019013.

- Moore, David W. (16 June 2005). "Three in Four Americans Believe in Paranormal". Gallup.

- "Eastern or New Age Beliefs, 'Evil Eye'". Many Americans Mix Multiple Faiths. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 December 2009.

- ^ "Science and Engineering Indicators: Chapter 7.Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (23 December 1998). "BV Raman Dies". New York Times, 23 December 1998. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- Dipankar Das. "Fame and Fortune". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "Soothsayers offer heavenly help". BBC News. 2 September 1999. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "In countries such as India, where only a small intellectual elite has been trained in Western physics, astrology manages to retain here and there its position among the sciences." David Pingree and Robert Gilbert, "Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times". Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008

- Mohan Rao, Female foeticide: where do we go? Indian Journal of Medical Ethics October–December 2001 9(4)

- "Indian Astrology vs Indian Science". BBC. 31 May 2001.

- "Guidelines for Setting up Departments of Vedic Astrology in Universities Under the Purview of University Grants Commission". Government of India, Department of Education. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

There is an urgent need to rejuvenate the science of Vedic Astrology in India, to allow this scientific knowledge to reach to the society at large and to provide opportunities to get this important science even exported to the world

- 'Astrology is a science: Bombay HC', The Times of India, 3 February 2011

- Shwalb, David W.; Shwalb, Barbara J. (1996). Japanese childrearing: two generations of scholarship. ISBN 9781572300811. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Kumon, Shumpei; Rosovsky, Henry (1992). The Political Economy of Japan: Cultural and social dynamics. ISBN 9780804719919. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Wedel, Theodore Otto (2003) . "9: Astrology in Gower and Chaucer". Mediæval Attitude Toward Astrology, Particularly in England. Kessinger. pp. 131–156.

The literary interest in astrology, which had been on the increase in England throughout the fourteenth century, culminated in the works of Gower and Chaucer. Although references to astrology were already frequent in the romances of the fourteenth century, these still retained the signs of being foreign importations. It was only in the fifteenth century that astrological similes and embellishments became a matter of course in the literature of England.

Such innovations, one must confess, were due far more to Chaucer than to Gower. Gower, too, saw artistic possibilities in the new astrological learning, and promptly used these in his retelling of the Alexander legend—but he confined himself, for the most part, to a bald rehearsal of facts and theories. It is, accordingly, as a part of the long encyclopaedia of natural science that he inserted into his Confessio Amantis, and in certain didactic passages of the Vox Clamantis and the Mirour de l'Omme, that Astrology figures most largely in his works ... Gower's sources on the subject of astrology ... were Albumasar's Introductorium in Astronomiam, the Pseudo-Aristotelian Secretum Secretorum, Brunetto Latini's Trésor, and the Speculum Astronomiae ascribed to Albert the Great. - Wood, 1970. pp.12–21

- ^ De Lacy, Hugh (October 1934). "Astrology in the Poetry of Edmund Spenser". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 33 (4): 520–543. JSTOR 27703949.

- ^ Camden Carroll, Jr. (April 1933). "Astrology in Shakespeare's Day". Isis. 19 (1): 26–73. doi:10.1086/346721. JSTOR 225186.

- Halstead, Frank G. (July 1939). "The Attitude of Lope de Vega toward Astrology and Astronomy". Hispanic Review. 7 (3): 205–219. doi:10.2307/470235. JSTOR 470235.

- Steiner, Arpad (August 1926). "Calderon's Astrologo Fingido in France". Modern Philology. 24 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1086/387623. JSTOR 433789.

- Campion, Nicholas.:A History of Western Astrology: Volume II: The Medieval and Modern Worlds. (Continuum Books, 2009) pp. 244–245 ISBN 978-1-84725-224-1

- Adams, Noah (10 September 2006). "'Pluto the Renewer' is no swan song". National Public Radio (NPR). Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- Vaughan, David (2004). "Frederick Ashton and His Ballets 1938". Ashton Archive. Archived from the original on 14 May 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The Twelve Signs: An Astrological Entertainment". Centre for New Zealand Music. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- Paglia, Camille. Sex, Art, and American Culture: Essays. Penguin Books, 1992, p. 114.

- Catton, Eleanor (2014-04-11). "Eleanor Catton on how she wrote The Luminaries". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

Sources

- Barton, Tamsyn (1994). Ancient Astrology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-11029-7.

- Campion, Nicholas (1982). An Introduction to the History of Astrology. ISCWA.

- Holden, James Herschel (2006). A History of Horoscopic Astrology (2nd ed.). AFA. ISBN 978-0-86690-463-6.

- Kay, Richard (1994). Dante's Christian Astrology. Middle Ages Series. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Long, A.A. (2005). "6: Astrology: arguments pro and contra". In Barnes, Jonathan; Brunschwig, J. (eds.). Science and Speculation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–191.

- Parker, Derek; Parker, Julia (1983). A history of astrology. Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-233-97576-4.

- Robbins, Frank E., ed. (1940). Ptolemy Tetrabiblos. Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library). ISBN 978-0-674-99479-9.

- Tester, S. J. (1999). A History of Western Astrology. Boydell & Brewer.

- Veenstra, J.R. (1997). Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France: Text and Context of Laurens Pignon's "Contre les Devineurs" (1411). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10925-4.

- Wedel, Theodore Otto (1920). The Medieval Attitude Toward Astrology: Particularly in England. Yale University Press.

- Wood, Chauncey (1970). Chaucer and the Country of the Stars: Poetical Uses of Astrological Imagery. Princeton University Press.

Further reading

- Forer, Bertram R. (January 1949). "The Fallacy of Personal Validation: A Classroom Demonstration of Gullibility". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 44 (1): 118–123. doi:10.1037/h0059240. PMID 18110193.

- Osborn, M. (2002). Time and the Astrolabe in The Canterbury Tales. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806134031.

- Thorndike, Lynn (1955). "The True Place of Astrology in the History of Science". Isis. 46 (3): 273–278. doi:10.1086/348412.

External links

- Digital International Astrology Library (ancient astrological works)

- www.biblioastrology.com Biblioastrology (The most complete bibliography exclusively devoted to astrology)

- Carl Sagan on Astrology

| Methods of divination | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||