This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) at 22:42, 5 August 2019 (→Nature of marriage). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:42, 5 August 2019 by Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) (→Nature of marriage)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Marriage in Australia is regulated by the federal Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) , which applies uniformly throughout Australia (including its external territories) to the exclusion of all state laws on the subject. Australian law recognises only monogamous marriages, being marriages of two people, including same-sex marriages, and does not recognise any other forms of union, including traditional Aboriginal marriages, polygamous marriages or concubinage. The marriage age for marriage in Australia is 18 years, but in "unusual and exceptional circumstances" a person aged 16 or 17 can marry with parental consent and authorisation by a court. A Notice of Intended Marriage is required to be lodged with the chosen marriage celebrant at least one month before the wedding. There is no citizenship or residency requirement for marriage in Australia, so that casual visitors can lawfully marry in Australia, provided that a domestic marriage celebrant is employed, the requisite notice given, and other domestic requirements satisfied.

Marriages performed abroad are normally recognised in Australia if entered into in accordance with the applicable foreign law, and do not require to be registered in Australia. It is not uncommon for Australian citizens or Australian residents to go abroad to marry. This may be to the family’s ancestral home country, to a destination wedding location or because they would not be permitted to marry in Australia.

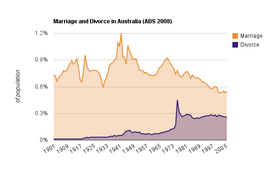

As was the case for other Western countries, marriage in Australia for most of the 20th century was done early and near-universally, particularly in the period after World War II to the early 1970s. Marriage at a young age was most often associated with pregnancy prior to marriage. Marriage was once seen as necessary for couples who cohabited. While some couples did cohabit before marriage, it was relatively uncommon until the 1950s in much of the Western world.

According to a 2008 Relationships Australia survey love, companionship and signifying a lifelong commitment were the top reasons for marriage.

Nature of marriage

Australian law recognises only monogamous marriages, being marriages of two people, including same-sex marriages, and does not recognise any other forms of union, including traditional Aboriginal marriages, polygamous marriages or concubinage. A person who goes through a marriage ceremony in Australia when still legally married to another person, whether under Australian law or a law of another country, commits an offence of bigamy, which is subject to a maximum 5 years imprisonment, and the marriage is void.

Since December 2017, Australian law has recognised same-sex marriage in Australia whether entered into in Australia or abroad. The original 1961 Marriage Act did not include a definition of marriage, leaving it to the courts to apply the common law definition. The Marriage Amendment Act 2004 defined, for the first time by statute, marriage as "the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life." The 2004 Act also expressly declared same-sex marriages entered into abroad were not to be recognised in Australia. This was in response to a lesbian couple getting married in Canada and applying for their marriage to be recognised in Australia. In 2017, the definition of "marriage" was changed, replacing the words "a man and a woman" with "2 people" and therefore allowing monogamous same-sex marriages. The changes also retrospectively recognised same-sex marriages performed in a foreign country, provided that such marriages were permitted under the laws of that foreign country.

A marriage must be entered into with the full consent of both parties, and it is an offence to force someone to marry them or another person, by the use of coercion, threat or deception, and whether in Australia or abroad. Full consent assumes a mental capacity to understand the nature of a marriage.

Most federal, state and territory laws also recognise de facto relationships, often on an equal basis to formal marital relationships.

Marriageable age

The marriageable age for marriage in Australia is 18 years, which is the age of majority in Australia in all states, but in "unusual and exceptional circumstances" a person aged 16 or 17 can marry with parental consent and authorisation by a Magistrates Court. The application to the court must be filed by a parent. For many years, courts have refused to accept a minor's pregnancy as a pressing consideration in deciding whether to allow an early marriage. In addition, the older partner must be over 18.

Until 1991, the marriage age was 16 for females and 18 for males, but a female 14 or 15 years (wanting to marry a male aged 18 or above) or a male 16 or 17 years (wanting to marry a female aged 16 or above) could apply to the court for permission to marry. The ages were equalised in 1991, with the relevant ages applying to females being raised to those applying to males.

Void marriages

A marriage entered into in Australia is void if:

- either party is already married (bigamy, polygamy).

- the parties are in a prohibited relationship: direct ancestor or descendant or sibling (whether full sibling or half sibling), including those arising from a legal adoption.

- the marriage was not solemnised by an authorised celebrant.

- there is no consent, for example due to duress, fraud, mistake as to identity, mistake as to the nature of ceremony, mental incapacity, or being below the marriageable age.

Marriages of non-citizens

Australian citizenship is not a requirement for marriage in Australia, nor for the recognition of a foreign marriage.

When one of the parties to a marriage is a non-citizen of Australia and the other is an Australian or New Zealand citizen or s permanent resident, the non-citizen may apply for an Australian “partner visa” to remain in Australia.

When marriages are entered into, whether in Australia or elsewhere, for the purpose of enabling the non-citizen to obtain an Australian visa to enter or stay in Australia, Australian authorities may investigate whether such a marriage is a sham. If found to be a sham, they may cancel the visa. Such behaviour also carries a possible 10 year jail sentence. Nevertheless, this does not effect the validity of the marriage itself.

Solemnisation of marriages in Australia

A marriage entered into in Australia is void (invalid) if it has not been “solemnised” by an authorised marriage celebrant. Only authorised marriage celebrants are allowed to solemnise marriages in Australia. There are three types of celebrants: ministers of religion, state and territory registry officers, and civil marriage celebrants. The only requirements for registration of a minister of religion is that he or she is nominated by a proclaimed "recognised denomination", is a resident in Australia, and is at least 21 years old. The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) was amended with the 2017 recognition of same-sex marriages to exempt a minister of religion or religious marriage celebrant or chaplain from the prohibition of sex discrimination by refusing to marry same-sex couples.

State and territory officers who are allowed to register marriages (under a state law) can also solemnise marriages (i.e. registry marriages).

Civil marriage celebrants are authorised to conduct and solemnise civil wedding ceremonies. For registration, they must meet a number of requirements, in addition to being at least 18 years old and "fit and proper" persons. The register will take into account knowledge of the law, commitment to advising couples about relationship counselling, community standing, criminal record, the existence of a conflict of interest or benefit to business, and "any other matter", which includes professional development and an adherence to a code of practice. Most marriages in Australia are solemnised by civil celebrants.

Notice of Intended Marriage

Couples must give their marriage celebrant a Notice of Intended Marriage at least one month before the intended wedding ceremony. The Notice is valid for 18 months. In exceptional circumstances, the couple can apply for a waiver of the one-month waiting period,

This Notice is not a marriage licence, as a couple does not normally require an official authorisation to marry, but a person under the age of 18 wishing to marry requires parental consent and the authorisation of a judge.

Wedding ceremony

The couple must wait at least one month after giving their marriage celebrant the Notice of Intended Marriage before the wedding ceremony. Both parties to the marriage must be present at the ceremony, with proxy marriages not permitted. The marriage celebrant and two witnesses over the age of 18 years must also be present, besides other guests. The witnesses must sign the certificate prepared by the celebrant.

The celebrant is required to recite the prescribed words to solemnise the marriage. Otherwise, almost anything is permitted. For example, it can be at any venue, indoors or outdoors, at any day or time, and follow any tradition or custom, or none at all.

Recognition of foreign marriages

It is not uncommon for Australian citizens or Australian residents to go abroad to marry. This may be to the family’s ancestral home country, to a destination wedding location or because they would not be permitted to marry in Australia. However, if a party to the marriage is not an Australian citizen, issues may arise with plans for the couple to move to and live in Australia. Marriage by itself to a non-citizen does not, for example, guarantee an Australian visa, let alone citizenship.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) can legalise signatures or seals that appear on Australian public documents (apostilles and authentications) and issues Certificates of No Impediment to Marriage (including witnessing the signature on the form).

In general, marriages entered into abroad are normally recognised in Australia as valid if they are valid according to the laws of the country in which the marriage took place, except that a marriage is not recognised as valid in Australia if:

- either person is still married, that is, if it is a polygamous marriage,

- either person is not of marriageable age,

- the parties are within a prohibited relationship, or

- there was no real consent.

So, for example, even though it may be legal for a person under the age of 18 to marry abroad, such a marriage will not be recognised as valid under Australian law, even when the underage partner turns 18.

Marriages performed abroad do not require to be registered in Australia, and it is advisable that the couple obtain and retain the marriage certificate from the relevant authority in the country in which the marriage took place.

Registration

It is compulsory for marriages entered into in Australia to be registered in the appropriate state or territory registry. In Australia, after the marriage ceremony, the marriage celebrant will send a certified copy of Notice to the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages of the state or territory in which the marriage took place. The Registrar uses the information in the Notice to register the marriage. A failure to register does not invalidate the marriage, but the registrar cannot issue a marriage certificate until the marriage is registered.

Marriages entered into abroad do not need to be registered in Australia.

Proof of marriage

In Australia, the marriage celebrant will at the time of marriage prepare three copies of a certificate, one for forwarding to the appropriate state or territory registry, one for the couple and one retained by the celebrant. While legally valid as proof of marriage, the couple’s copy is not generally acceptable as an official document.

The state or territory registrars will, on application by either spouse, issue a marriage certificate which is considered to be an acceptable and secure secondary identity document especially for the purposes of change of name, and needs to be obtained separately, for a fee, generally some time after the marriage. This document can be verified electronically by the Attorney-General of Australia's Document Verification Service. States and territories sometimes market commemorative marriage certificates, which generally have no official document status.

Marriage certificates are generally not used in Australia, other than to prove change-of-name, and proof of marital status for probate purposes or in a divorce application. Some visa categories require a certificate (where a partner is to be associated with a primary applicant), however there are similar categories of partner visas that do not.

In the case of foreign marriages, the foreign marriage certificate is normally adequate proof of marriage.

History

In colonial New South Wales marriage was often an arrangement of convenience. For female convicts, marriage was a way of escaping incarceration. Land leases were denied to those who were unmarried. On the other hand, there was a significant gender imbalance in the colony.

Until 1961, each Australian state and territory administered its own marriage laws. The Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) was the first federal law on the matter and set uniform Australia-wide rules for the recognition and solemnisation of marriages. In its current form, the Act recognises only monogamous (heterosexual or same-sex) marriages and does not recognise any other forms of union, such as traditional Aboriginal marriages polygamous marriages or concubinage.

The Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) replaced the previous faults-based divorce system with a no-fault divorce system, requiring only a twelve-month period of separation. The 1970s saw a significant rise in the divorce rate in Australia. This change has been attributed to a change in social attitudes: having once been considered acceptable only if there were severe problems, divorce was now widely considered acceptable if it was the preference of the partners.

In 2004, the Liberal Howard Government enacted the Marriage Amendment Act 2004 to expressly ban same-sex marriage in Australia. It defined marriage as "the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life".

Until the enactment of the 2004 amendment, there was no definition in the 1961 Act of "marriage", and the common law definition used in the English case Hyde v Hyde (1866) was taken as applicable. The definition pronounced by Lord Penzance in the case was: "I conceive that marriage, as understood in Christendom, may for this purpose be defined as the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all others". The 2004 amendment also banned the recognition of same-sex marriages performed in a foreign country. The definition of marriage was added to the wedding ceremony speeches as a monitum; without it, ceremonies would be considered invalid.

In 2009, the Labor Rudd Government enacted the Family Law Act 2009, which recognised the property rights of each partner of a de facto relationship, including a same-sex relationship, for the purposes of the Family Law Act 1975.

The 2014 Marriage Amendment (Celebrant Administration and Fees) Act amended the Marriage Act 1961 in relation to celebrants and other issues.

The 2017 Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act again changed the definition of "marriage" under the Marriage Act 1961, replacing the words "a man and a woman" with "2 people" and therefore allowing monogamous same-sex marriages. The Act also reversed the 2004 Amendment and retrospectively recognised same-sex marriages performed in a foreign country, provided that such marriages were permitted under the laws of that foreign country.

Social change

In 2009, the Australian Bureau of Statistics noted that "The proportion of adults living with a partner has declined during the last two decades, from 65% in 1986, to 61% in 2006". The proportion of Australians who are married fell from 62% to 52% over the same period.

Common-law marriages have increased significantly in recent decades, from 4% to 9% between 1986 and 2006. Cohabitation is often a prelude to marriage and reflects an increasing desire to attain financial independence before having children. In 2015, 81% of all those marrying were already living together.

Since 1999, civil celebrants have overseen the majority of marriages. In 2017, 78% of marriages were solemnised by a civil celebrant.

On its inception, the Commonwealth Public Service placed a bar on the employment of married women, so that married women could only be employed as temporary staff. Any female employee was required to resign upon marrying. This bar restricted women's opportunities for promotion. After a long campaign the bar was lifted in 1966.

In 1971, more than three quarters of women surveyed placed being a mother before their career. By 1991 this figure had dropped to one quarter.

By the 1980s there was a clear trend towards delaying first marriage. In 1989, more than one woman in five had not married by the age of 30. Between 1990 and 2010, the median age at first marriage increased by more than three years for both women and men (from 24.3 years to 27.9 years for women, and from 26.5 years to 29.6 years for men).

Divorce in Australia

The crude divorce rate was 2.0 divorces per 1,000 estimated resident population in 2014 and 2015, down from 2.1 in 2013. The median duration from marriage to divorce in 2015 was 12.1 years. The median age at divorce was 45.3 years for men and 42.7 years for women.

Same-sex marriage

See also: Same-sex marriage in Australia, History of same-sex marriage in Australia, and Australian Marriage Law Postal SurveyThe Marriage Act 1961 was amended in December 2017 by the Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act 2017 to amend the definition of marriage and to recognise same-sex marriage in Australia whether entered into in Australia or abroad. The original Marriage Act did not include a definition of marriage, leaving it to the courts to apply the common law definition. The Marriage Amendment Act 2004 defined, for the first time by statute, marriage as "the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life." The 2004 Act also expressly declared same-sex marriages entered into abroad were not to be recognised in Australia. This was in response to a lesbian couple getting married in Canada and applying for their marriage to be recognised in Australia.

Since 2009, same-sex couples were included in Australia's de facto relationship laws, unions which provide couples with most, though not all, of the same rights as married couples. Same-sex and opposite-sex de facto couples can continue to access domestic partnership registries in New South Wales, Tasmania, South Australia and Victoria. Civil partnerships/unions are performed in Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory. Western Australia and the Northern Territory do not recognise civil unions, civil partnerships or a relationship register, but do recognise the unregistered cohabitation of de facto couples under their laws.

See also

- Marriage Act 1961 (Australia)

- Australian Aboriginal kinship

- Australian family law

- Celebrant (Australia)

- Polygamy in Australia

- Same-sex marriage in Australia

- Voidable marriages (Australia)

References

- ^ Australian Government, Law Reform Commission - Aboriginal Traditional Marriage: Areas for Recognition

- ^ "Your Legal Obligations". Australian Marriage Celebrants. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ McDonald, P. (1992). "The 1980s: Social and Economic Change Affecting Families". In Jagtenberg, Tom; D'Alton, Phillip (eds.). Four Dimensional Social Space. Pymble, Sydney: Harper Educational Publishers. pp. 126–128. ISBN 0063121271.

- Thornton, Arland; William G. Axinn; Yu Xie (2008). Marriage and Cohabitation. University of Chicago Press. p. 72. ISBN 0226798682. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "Why do people get married?". Relationships Australia. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Marriage Act 1961, s 94".

- Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act 2017

- "Same-sex marriage bill passes House of Representatives, paving way for first gay weddings". ABC News. 7 December 2017.

- "When can you lodge your Notice for Intended Marriage?". ABC News. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- The definition is found in Hyde v Hyde (1866) {L.R.} 1 P. & D. 130: "I conceive that marriage, as understood in Christendom, may for this purpose be defined as the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all others".

- Michael, Quinlan (2016). "Marriage, Tradition, Multiculturalism and the Accommodation of Difference in Australia". The University of Notre Dame Australia Law Review. 18 (1). ISSN 1441-9769.

- "Marriage Amendment Act 2004". comlaw.gov.au.

- Wall, Louisa (13 October 2017). "Australia's marriage equality process did not have to be so politicised | Louisa Wall". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act

- Children’s Rights: Australia

- "Lawstuff Australia - Know Your Rights - Topics - Marriage".

- http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2004C05245

- Sex Discrimination Amendment Act 1991

- "ComLaw Acts - Attachment - Sex Discrimination Amendment Act 1991". Scaleplus.law.gov.au. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Marriage Act 1961, s 23B".

- Partner visa (apply in Australia)

- 'Easy money' for sham marriage: The women targeted by global syndicate

- Notice of Intended Marriage (Form 13 - regulation 38 - Marriage Act 1961).

- Getting married

- "Same-sex marriage: How Australia's first wedding can happen within a month". ABC News. 13 December 2017.

- Marriage Act 1961, s.44

- Marriage Act 1961, s.46

- Marriage Act 1961, s.43

- "Births, deaths and marriages – Fact sheet 89". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- Agency, Digital Transformation. "Births, deaths and marriages registries - australia.gov.au". Australia.gov.au. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Marriage certificate". Bdm.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Partner visa (subclasses 820 and 801)". Border.gov.au. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Edgar, Don (2012). Men Mateship Marriage. HarperCollins Australia. ISBN 0730496589. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ Clancy, Laurie (2004). Culture and Customs of Australia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0313321698. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- Halford, W. Kim (2011). Marriage and Relationship Education: What Works and How to Provide It. Guilford Press. p. 13. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|isbn1609181573=(help) - Hyde v. Hyde and Woodmansee {L.R.} 1 P. & D. 130.

- Hyde v Hyde casenote Archived 2014-03-29 at archive.today.

- The 2004 Amendment inserted 88EA "Certain unions are not marriages" into the 1961 Act.

- "Couples seek to bypass 'downer' legal passage in wedding vows". ABC News. 1 June 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2014A00025

- ^ http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features20March%202009

- Uhlmann, Allon J. (2006). Family, Gender and Kinship in Australia: The Social and Cultural Logic of Practice and Subjectivity. Ashgate Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 0754680266. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3310.0

- "Marriages and Divorces, Australia, 2017". Australian Bureau of Statistics. ABS. 27 Nov 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- http://timeline.awava.org.au/archives/264

- "The long, slow demise of the "marriage bar" | Inside Story". Inside Story. 2016-12-08. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. "Main Features - Love Me Do". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Same-sex marriage bill passes House of Representatives, paving way for first gay weddings". ABC News. 7 December 2017.

- "When can you lodge your Notice for Intended Marriage?". ABC News. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- The definition is found in Hyde v Hyde (1866) {L.R.} 1 P. & D. 130: "I conceive that marriage, as understood in Christendom, may for this purpose be defined as the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all others".

- Michael, Quinlan (2016). "Marriage, Tradition, Multiculturalism and the Accommodation of Difference in Australia". The University of Notre Dame Australia Law Review. 18 (1). ISSN 1441-9769.

- "Marriage Amendment Act 2004". comlaw.gov.au.

- Wall, Louisa (13 October 2017). "Australia's marriage equality process did not have to be so politicised | Louisa Wall". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "SSM: What legal benefits do married couples have that de facto couples do not?". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 September 2017.

- "FAMILY LAW ACT 1975 - SECT 4AA De facto relationships". www.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

External links

- Getting married - Government information

- Births, deaths and marriages registries - Government information