This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Begoon (talk | contribs) at 12:58, 30 October 2019 (oops - reverted to wrong version. Sorry JamesVilla. Edit conflicts X a million... Thatjakelad - Please follow WP:BRD. You made a bold change, it was reverted, now discuss on the talk page, don't edit war. Thank you.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:58, 30 October 2019 by Begoon (talk | contribs) (oops - reverted to wrong version. Sorry JamesVilla. Edit conflicts X a million... Thatjakelad - Please follow WP:BRD. You made a bold change, it was reverted, now discuss on the talk page, don't edit war. Thank you.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Centre-left political party in the United Kingdom

The Labour Party is a centre-left political party in the United Kingdom that has been described as an alliance of social democrats, democratic socialists and trade unionists. The party's platform emphasises greater state intervention, social justice and strengthening workers' rights.

The Labour Party was founded in 1900, having grown out of the trade union movement and socialist parties of the nineteenth century. It overtook the Liberal Party to become the main opposition to the Conservative Party in the early 1920s, forming two minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in the 1920s and early 1930s. Labour served in the wartime coalition of 1940–1945, after which Clement Attlee's Labour government established the National Health Service and expanded the welfare state from 1945 to 1951. Under Harold Wilson and James Callaghan, Labour again governed from 1964 to 1970 and 1974 to 1979. In the 1990s, Tony Blair took Labour closer to the centre as part of his "New Labour" project, which governed the UK under Blair and then Gordon Brown from 1997 to 2010. Since Jeremy Corbyn took over the leadership in 2015 from Ed Miliband, the party has moved leftward.

Labour is currently the Official Opposition in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, having won the second-largest number of seats in the 2017 general election. The Labour Party is currently the largest party in the Welsh Assembly, forming the main party in the current Welsh government. The party is the third-largest in the Scottish Parliament.

Labour is a member of the Party of European Socialists and Progressive Alliance, holds observer status in the Socialist International, and sits with the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament. The party includes semi-autonomous Scottish, Welsh branches, and supports the Social Democratic and Labour Party in Northern Ireland, although it still organises there. As of 2017, Labour had the largest membership of any party in Western Europe.

History

Main articles: History of the Labour Party (UK) and History of the socialist movement in the United KingdomFounding

The Labour Party originated in the late 19th century, meeting the demand for a new political party to represent the interests and needs of the urban working class, a demographic which had increased in number, and many of whom only gained suffrage with the passage of the Representation of the People Act 1884. Some members of the trades union movement became interested in moving into the political field, and after further extensions of the voting franchise in 1867 and 1885, the Liberal Party endorsed some trade-union sponsored candidates. The first Lib–Lab candidate to stand was George Odger in the Southwark by-election of 1870. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time, with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the Independent Labour Party, the intellectual and largely middle-class Fabian Society, the Marxist Social Democratic Federation and the Scottish Labour Party.

At the 1895 general election, the Independent Labour Party put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. Keir Hardie, the leader of the party, believed that to obtain success in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups. Hardie's roots as a lay preacher contributed to an ethos in the party which led to the comment by 1950s General Secretary Morgan Phillips that "Socialism in Britain owed more to Methodism than Marx".

Labour Representation Committee, 1900–1906

Main article: Labour Representation Committee (1900)

In 1899, a Doncaster member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, Thomas R. Steels, proposed in his union branch that the Trade Union Congress call a special conference to bring together all left-wing organisations and form them into a single body that would sponsor Parliamentary candidates. The motion was passed at all stages by the TUC, and the proposed conference was held at the Congregational Memorial Hall on Farringdon Street, London on 26 and 27 February 1900. The meeting was attended by a broad spectrum of working-class and left-wing organisations—trades unions represented about one third of the membership of the TUC delegates.

After a debate, the 129 delegates passed Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." This created an association called the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), meant to co-ordinate attempts to support MPs sponsored by trade unions and represent the working-class population. It had no single leader, and in the absence of one, the Independent Labour Party nominee Ramsay MacDonald was elected as Secretary. He had the difficult task of keeping the various strands of opinions in the LRC united. The October 1900 "Khaki election" came too soon for the new party to campaign effectively; total expenses for the election only came to £33. Only 15 candidatures were sponsored, but two were successful: Keir Hardie in Merthyr Tydfil and Richard Bell in Derby.

Support for the LRC was boosted by the 1901 Taff Vale Case, a dispute between strikers and a railway company that ended with the union being ordered to pay £23,000 damages for a strike. The judgement effectively made strikes illegal, since employers could recoup the cost of lost business from the unions. The apparent acquiescence of the Conservative Government of Arthur Balfour to industrial and business interests (traditionally the allies of the Liberal Party in opposition to the Conservatives' landed interests) intensified support for the LRC against a government that appeared to have little concern for the industrial proletariat and its problems.

In the 1906 election, the LRC won 29 seats—helped by a secret 1903 pact between Ramsay MacDonald and Liberal Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone that aimed to avoid splitting the opposition vote between Labour and Liberal candidates in the interest of removing the Conservatives from office.

In their first meeting after the election the group's Members of Parliament decided to adopt the name "The Labour Party" formally (15 February 1906). Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (in effect, the leader), although only by one vote over David Shackleton after several ballots. In the party's early years the Independent Labour Party (ILP) provided much of its activist base as the party did not have individual membership until 1918 but operated as a conglomerate of affiliated bodies. The Fabian Society provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party. One of the first acts of the new Liberal Government was to reverse the Taff Vale judgement.

The People's History Museum in Manchester holds the minutes of the first Labour Party meeting in 1906 and has them on display in the Main Galleries. Also within the museum is the Labour History Archive and Study Centre, which holds the collection of the Labour Party, with material ranging from 1900 to the present day.

Early years, 1906–1923

The December 1910 election saw 42 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons, a significant victory since, a year before the election, the House of Lords had passed the Osborne judgment ruling that trade union members would have to 'opt in' to sending contributions to Labour, rather than their consent being presumed. The governing Liberals were unwilling to repeal this judicial decision with primary legislation. The height of Liberal compromise was to introduce a wage for Members of Parliament to remove the need to involve the trade unions. By 1913, faced with the opposition of the largest trade unions, the Liberal government passed the Trade Disputes Act to allow unions to fund Labour MPs once more without seeking the express consent of their members.

During the First World War, the Labour Party split between supporters and opponents of the conflict but opposition to the war grew within the party as time went on. Ramsay MacDonald, a notable anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party and Arthur Henderson became the main figure of authority within the party. He was soon accepted into Prime Minister Asquith's war cabinet, becoming the first Labour Party member to serve in government.

Despite mainstream Labour Party's support for the coalition the Independent Labour Party was instrumental in opposing conscription through organisations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship while a Labour Party affiliate, the British Socialist Party, organised a number of unofficial strikes.

Arthur Henderson resigned from the Cabinet in 1917 amid calls for party unity to be replaced by George Barnes. The growth in Labour's local activist base and organisation was reflected in the elections following the war, the co-operative movement now providing its own resources to the Co-operative Party after the armistice. The Co-operative Party later reached an electoral agreement with the Labour Party.

Henderson turned his attention to building a strong constituency-based support network for the Labour Party. Previously, it had little national organisation, based largely on branches of unions and socialist societies. Working with Ramsay MacDonald and Sidney Webb, Henderson in 1918 established a national network of constituency organisations. They operated separately from trade unions and the National Executive Committee and were open to everyone sympathetic to the party's policies. Secondly, Henderson secured the adoption of a comprehensive statement of party policies, as drafted by Sidney Webb. Entitled "Labour and the New Social Order," it remained the basic Labour platform until 1950. It proclaimed a socialist party whose principles included a guaranteed minimum standard of living for everyone, nationalisation of industry, and heavy taxation of large incomes and of wealth. It was in 1918 that Clause IV, as drafted by Sidney Webb, was adopted into Labour's constitution, committing the party to work towards "the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange."

With the Representation of the People Act 1918, almost all adult men (excepting only peers, criminals and lunatics) and most women over the age of thirty were given the right to vote, almost tripling the British electorate at a stroke, from 7.7 million in 1912 to 21.4 million in 1918. This set the scene for a surge in Labour representation in parliament. The Communist Party of Great Britain was refused affiliation to the Labour Party between 1921 and 1923.

Meanwhile, the Liberal Party declined rapidly, and the party also suffered a catastrophic split which allowed the Labour Party to gain much of the Liberals' support. With the Liberals thus in disarray, Labour won 142 seats in 1922, making it the second largest political group in the House of Commons and the official opposition to the Conservative government. After the election Ramsay MacDonald was voted the first official leader of the Labour Party.

The first Labour government, and a period in opposition, 1923–1929

Main article: First MacDonald ministry

The 1923 general election was fought on the Conservatives' protectionist proposals but, although they got the most votes and remained the largest party, they lost their majority in parliament, necessitating the formation of a government supporting free trade. Thus, with the acquiescence of Asquith's Liberals, Ramsay MacDonald became the first ever Labour Prime Minister in January 1924, forming the first Labour government, despite Labour only having 191 MPs (less than a third of the House of Commons).

Because the government had to rely on the support of the Liberals it was unable to pass any radical legislation. The most significant achievement was the Wheatley Housing Act, which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rental to low paid workers. Legislation on education, unemployment, social insurance and tenant protection was also passed. Although no major changes were introduced, the main achievement of the government was to demonstrate that Labour were capable of governing.

While there were no major labour strikes during his term, MacDonald acted swiftly to end those that did erupt. When the Labour Party executive criticised the government, he replied that, "public doles, Poplarism , strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism, but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement."

The government collapsed after only nine months when the Liberals voted for a Select Committee inquiry into the Campbell Case, a vote which MacDonald had declared to be a vote of confidence. The ensuing 1924 general election saw the publication, four days before polling day, of the forged Zinoviev letter, in which Moscow talked about a Communist revolution in Britain. The letter had little impact on the Labour vote—which held up. It was the collapse of the Liberal party that led to the Conservative landslide. The Conservatives were returned to power although Labour increased its vote from 30.7% to a third of the popular vote, most Conservative gains being at the expense of the Liberals. However many Labourites for years blamed their defeat on foul play (the Zinoviev letter), thereby according to A. J. P. Taylor misunderstanding the political forces at work and delaying needed reforms in the party.

In opposition MacDonald continued his policy of presenting the Labour Party as a moderate force. During the General Strike of 1926 the party opposed the general strike, arguing that the best way to achieve social reforms was through the ballot box. The leaders were also fearful of Communist influence orchestrated from Moscow.

The Party had a distinctive and suspicious foreign policy based on pacifism. Its leaders believed that peace was impossible because of capitalism, secret diplomacy, and the trade in armaments. That is it stressed material factors that ignored the psychological memories of the Great War, and the highly emotional tensions regarding nationalism and the boundaries of the countries.

Second Labour government, 1929–1931

Main article: Second MacDonald ministry

In the 1929 general election, the Labour Party became the largest in the House of Commons for the first time, with 287 seats and 37.1% of the popular vote. However MacDonald was still reliant on Liberal support to form a minority government. MacDonald went on to appoint Britain's first woman cabinet minister; Margaret Bondfield, who was appointed Minister of Labour.

MacDonald's second government was in a stronger parliamentary position than his first, and in 1930 Labour was able to pass legislation to raise unemployment pay, improve wages and conditions in the coal industry (i.e. the issues behind the General Strike) and pass a housing act which focused on slum clearances.

The government, however, soon found itself engulfed in crisis: the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and eventual Great Depression occurred soon after the government came to power, and the slump in global trade hit Britain hard. By the end of 1930 unemployment had doubled to over two and a half million. The government had no effective answers to the deteriorating financial situation, and by 1931 there was much fear that the budget was unbalanced, which was born out by the independent May Report which triggered a confidence crisis and a run on the pound. The cabinet deadlocked over its response, with several influential members unwilling to support the budget cuts (in particular a cut in the rate of unemployment benefit) which were pressed by the civil service and opposition parties. Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden refused to consider deficit spending or tariffs as alternative solutions. When a final vote was taken, the Cabinet was split 11-9 with a minority, including many political heavyweights such as Arthur Henderson and George Lansbury, threatening to resign rather than agree to the cuts. The unworkable split, on 24 August 1931, made the government resign. MacDonald was encouraged by King George V to form an all-party National Government to deal with the immediate crisis.

The financial crisis grew worse and decisive government action was needed as the leaders of both the Conservative and Liberal Parties met with King George V, and MacDonald, at first to discuss support for the spending cuts but later to discuss the shape of the next government. The king played the central role in demanding a National government be formed. On 24 August, MacDonald agreed to form a National Government composed of men from all parties with the specific aim of balancing the Budget and restoring confidence. The new cabinet had four Labourites (who formed a "National Labour" group) who stood with MacDonald, plus four Conservatives (led by Baldwin, Chamberlain) and two Liberals. MacDonald's moves aroused great anger among a large majority of Labour Party activists who felt betrayed. Labour unions were strongly opposed and the Labour Party officially repudiated the new National government. It expelled MacDonald and his supporters and made Henderson the leader of the main Labour party. Henderson led it into the general election on 27 October against the three-party National coalition. It was a disaster for Labour, which was reduced to a small minority of 52 seats. The Conservative-dominated National Government, led by MacDonald won the largest landslide in British political history.

In 1931 Labour campaigned on opposition to public spending cuts, but found it difficult to defend the record of the party's former government and the fact that most of the cuts had been agreed before it fell. Historian Andrew Thorpe argues that Labour lost credibility by 1931 as unemployment soared, especially in coal, textiles, shipbuilding, and steel. The working class increasingly lost confidence in the ability of Labour to solve the most pressing problem.

The 2.5 million Irish Catholics in England and Scotland were a major factor in the Labour base in many industrial areas. The Catholic Church had previously tolerated the Labour Party, and denied that it represented true socialism. However, the bishops by 1930 had grown increasingly alarmed at Labour's policies toward Communist Russia, toward birth control and especially toward funding Catholic schools. They warned its members. The Catholic shift against Labour and in favour of the National government played a major role in Labour's losses.

Labour in opposition, 1931–1940

Arthur Henderson, elected in 1931 to succeed MacDonald, lost his seat in the 1931 general election. The only former Labour cabinet member who had retained his seat, the pacifist George Lansbury, accordingly became party leader.

The party experienced another split in 1932 when the Independent Labour Party, which for some years had been increasingly at odds with the Labour leadership, opted to disaffiliate from the Labour Party and embarked on a long, drawn-out decline.

Lansbury resigned as leader in 1935 after public disagreements over foreign policy. He was promptly replaced as leader by his deputy, Clement Attlee, who would lead the party for two decades. The party experienced a revival in the 1935 general election, winning 154 seats and 38% of the popular vote, the highest that Labour had achieved.

As the threat from Nazi Germany increased, in the late 1930s the Labour Party gradually abandoned its pacifist stance and came to support re-armament, largely due to the efforts of Ernest Bevin and Hugh Dalton who by 1937 had also persuaded the party to oppose Neville Chamberlain's policy of appeasement.

Wartime coalition, 1940–1945

The party returned to government in 1940 as part of the wartime coalition. When Neville Chamberlain resigned in the spring of 1940, incoming Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to bring the other main parties into a coalition similar to that of the First World War. Clement Attlee was appointed Lord Privy Seal and a member of the war cabinet, eventually becoming the United Kingdom's first Deputy Prime Minister.

A number of other senior Labour figures also took up senior positions: the trade union leader Ernest Bevin, as Minister of Labour, directed Britain's wartime economy and allocation of manpower, the veteran Labour statesman Herbert Morrison became Home Secretary, Hugh Dalton was Minister of Economic Warfare and later President of the Board of Trade, while A. V. Alexander resumed the role he had held in the previous Labour Government as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Attlee government, 1945–1951

Main article: Attlee ministry

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, Labour resolved not to repeat the Liberals' error of 1918, and promptly withdrew from government, on trade union insistence, to contest the 1945 general election in opposition to Churchill's Conservatives. Surprising many observers, Labour won a formidable victory, winning just under 50% of the vote with a majority of 159 seats.

Although Clement Attlee was no great radical himself, Attlee's government proved one of the most radical British governments of the 20th century, enacting Keynesian economic policies, presiding over a policy of nationalising major industries and utilities including the Bank of England, coal mining, the steel industry, electricity, gas, and inland transport (including railways, road haulage and canals). It developed and implemented the "cradle to grave" welfare state conceived by the economist William Beveridge. To this day, most people in the United Kingdom see the 1948 creation of Britain's National Health Service (NHS) under health minister Aneurin Bevan, which gave publicly funded medical treatment for all, as Labour's proudest achievement. Attlee's government also began the process of dismantling the British Empire when it granted independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) the following year. At a secret meeting in January 1947, Attlee and six cabinet ministers, including Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, decided to proceed with the development of Britain's nuclear weapons programme, in opposition to the pacifist and anti-nuclear stances of a large element inside the Labour Party.

Labour went on to win the 1950 general election, but with a much-reduced majority of five seats. Soon afterwards, defence became a divisive issue within the party, especially defence spending (which reached a peak of 14% of GDP in 1951 during the Korean War), straining public finances and forcing savings elsewhere. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell, introduced charges for NHS dentures and spectacles, causing Bevan, along with Harold Wilson (then President of the Board of Trade), to resign over the dilution of the principle of free treatment on which the NHS had been established.

In the 1951 general election, Labour narrowly lost to Churchill's Conservatives, despite receiving the larger share of the popular vote – its highest ever vote numerically. Most of the changes introduced by the 1945–51 Labour government were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "post-war consensus" that lasted until the late 1970s. Food and clothing rationing, however, still in place since the war, were swiftly relaxed, then abandoned from about 1953.

Post-war consensus, 1951–1964

Following the defeat of 1951, the party spent 13 years in opposition. The party suffered an ideological split, between the party's left-wing followers of Aneurin Bevan (known as Bevanites), and the right-wing of the party following Hugh Gaitskell (known as Gaitskellites) while the postwar economic recovery and the social effects of Attlee's reforms made the public broadly content with the Conservative governments of the time. The ageing Attlee contested his final general election in 1955, which saw Labour lose ground, and he retired shortly after.

His replacement, Hugh Gaitskell, associated with the right wing of the party, struggled in dealing with internal party divisions in the late 1950s and early 1960s (particularly over Clause IV of the Labour Party Constitution, which was viewed as Labour's commitment to nationalisation and Gaitskell wanted scrapped). Under Gaitskell, Labour lost their third general election in a row in 1959. In 1963, Gaitskell's sudden death from a rare illness made way for Harold Wilson to lead the party.

Wilson government, 1964–1970

Main article: First Wilson ministry

A downturn in the economy and a series of scandals in the early 1960s (the most notorious being the Profumo affair) had engulfed the Conservative government by 1963. The Labour Party returned to government with a 4-seat majority under Wilson in the 1964 general election but increased its majority to 96 in the 1966 general election.

Wilson's government was responsible for a number of sweeping social and educational reforms under the leadership of Home Secretary Roy Jenkins such as the abolishment of the death penalty in 1964, the legalisation of abortion and homosexuality (initially only for men aged 21 or over, and only in England and Wales) in 1967 and the abolition of theatre censorship in 1968. Comprehensive education was expanded and the Open University created. However Wilson's government had inherited a large trade deficit that led to a currency crisis and ultimately a doomed attempt to stave off devaluation of the pound. Labour went on to lose the 1970 general election to the Conservatives under Edward Heath.

Spell in opposition, 1970–1974

After losing the 1970 general election, Labour returned to opposition, but retained Harold Wilson as Leader. Heath's government soon ran into trouble over Northern Ireland and a dispute with miners in 1973 which led to the "three-day week". The 1970s proved a difficult time to be in government for both the Conservatives and Labour due to the 1973 oil crisis which caused high inflation and a global recession.

The Labour Party was returned to power again under Wilson a few weeks after the February 1974 general election, forming a minority government with the support of the Ulster Unionists. The Conservatives were unable to form a government alone as they had fewer seats despite receiving more votes numerically. It was the first general election since 1924 in which both main parties had received less than 40% of the popular vote and the first of six successive general elections in which Labour failed to reach 40% of the popular vote. In a bid to gain a majority, a second election was soon called for October 1974 in which Labour, still with Harold Wilson as leader, won a slim majority of three, gaining just 18 seats taking its total to 319.

Majority to minority, 1974–1979

Main article: Labour Government 1974–79For much of its time in office the Labour government struggled with serious economic problems and a precarious majority in the Commons, while the party's internal dissent over Britain's membership of the European Economic Community, which Britain had entered under Edward Heath in 1972, led in 1975 to a national referendum on the issue in which two thirds of the public supported continued membership.

Harold Wilson's personal popularity remained reasonably high but he unexpectedly resigned as Prime Minister in 1976 citing health reasons, and was replaced by James Callaghan. The Wilson and Callaghan governments of the 1970s tried to control inflation (which reached 23.7% in 1975) by a policy of wage restraint. This was fairly successful, reducing inflation to 7.4% by 1978. However it led to increasingly strained relations between the government and the trade unions.

Fear of advances by the nationalist parties, particularly in Scotland, led to the suppression of a report from Scottish Office economist Gavin McCrone that suggested that an independent Scotland would be "chronically in surplus". By 1977 by-election losses and defections to the breakaway Scottish Labour Party left Callaghan heading a minority government, forced to do deals with smaller parties in order to govern. An arrangement negotiated in 1977 with Liberal leader David Steel, known as the Lib–Lab pact, ended after one year. Deals were then forged with various small parties including the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru, prolonging the life of the government.

The nationalist parties, in turn, demanded devolution to their respective constituent countries in return for their supporting the government. When referendums for Scottish and Welsh devolution were held in March 1979 the Welsh devolution referendum saw a large majority vote against, while the Scottish referendum returned a narrow majority in favour without reaching the required threshold of 40% support. When the Labour government duly refused to push ahead with setting up the proposed Scottish Assembly, the SNP withdrew its support for the government: this finally brought the government down as the Conservatives triggered a vote of confidence in Callaghan's government that was lost by a single vote on 28 March 1979, necessitating a general election.

By 1978 the economy had started to show signs of recovery, with inflation falling to single digits, unemployment falling, and living standards starting to rise during the year. Labour's opinion poll ratings also improved, with most showing the party to have gained a narrow lead. Callaghan had been widely expected to call a general election in the autumn of 1978 to take advantage of the improved situation. In the event, he decided to extend his wage restraint policy for another year hoping that the economy would be in better shape for a 1979 election. However, during the winter of 1978–79 there were widespread strikes among lorry drivers, railway workers, car workers and local government and hospital workers in favour of higher pay-rises that caused significant disruption to everyday life. These events came to be dubbed the "Winter of Discontent".

In the 1979 general election Labour was heavily defeated by the Conservatives now led by Margaret Thatcher. The Labour vote held up in the election, with the party receiving a similar number of votes as in 1974. However, the Conservative Party achieved big increases in support in the Midlands and South of England, benefiting from both a surge in turnout and votes lost by the ailing Liberals.

Internal conflict and opposition, 1979–1997

After its defeat in the 1979 general election the Labour Party underwent a period of internal rivalry between the left represented by Tony Benn, and the right represented by Denis Healey. The election of Michael Foot as leader in 1980, and the leftist policies he espoused, such as unilateral nuclear disarmament, leaving the European Economic Community and NATO, closer governmental influence in the banking system, the creation of a national minimum wage and a ban on fox hunting led in 1981 to four former cabinet ministers from the right of the Labour Party (Shirley Williams, William Rodgers, Roy Jenkins and David Owen) forming the Social Democratic Party. Benn was only narrowly defeated by Healey in a bitterly fought deputy leadership election in 1981 after the introduction of an electoral college intended to widen the voting franchise to elect the leader and their deputy. By 1982, the National Executive Committee had concluded that the entryist Militant tendency group were in contravention of the party's constitution. The Militant newspaper's five member editorial board were expelled on 22 February 1983.

The Labour Party was defeated heavily in the 1983 general election, winning only 27.6% of the vote, its lowest share since 1918, and receiving only half a million votes more than the SDP-Liberal Alliance who leader Michael Foot condemned for "siphoning" Labour support and enabling the Conservatives to greatly increase their majority of parliamentary seats. The party manifesto for this election was termed by critics as "the longest suicide note in history".

Foot resigned and was replaced as leader by Neil Kinnock, with Roy Hattersley as his deputy. The new leadership progressively dropped unpopular policies. The miners' strike of 1984–85 over coal mine closures, which divided the NUM as well as the Labour Party, and the Wapping dispute led to clashes with the left of the party, and negative coverage in most of the press. Tabloid vilification of the so-called loony left continued to taint the parliamentary party by association from the activities of "extra-parliamentary" militants in local government.

The alliances which campaigns such as Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners forged between lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) and labour groups, as well as the Labour Party itself, also proved to be an important turning point in the progression of LGBT issues in the UK. At the 1985 Labour Party conference in Bournemouth, a resolution committing the party to support LGBT equality rights passed for the first time due to block voting support from the National Union of Mineworkers.

Labour improved its performance in 1987, gaining 20 seats and so reducing the Conservative majority from 143 to 102. They were now firmly re-established as the second political party in Britain as the Alliance had once again failed to make a breakthrough with seats. A merger of the SDP and Liberals formed the Liberal Democrats. Following the 1987 election, the National Executive Committee resumed disciplinary action against members of Militant, who remained in the party, leading to further expulsions of their activists and the two MPs who supported the group. During the 1980s radically socialist members of the party were often described as the "loony left", particularly in the print media. The print media in the 1980s also began using the pejorative "hard left" to sometimes describe Trotskyist groups such as the Militant tendency, Socialist Organiser and Socialist Action.

In 1988, Kinnock was challenged by Tony Benn for the party leadership. Based on the percentages, 183 members of parliament supported Kinnock, while Benn was backed by 37. With a clear majority, Kinnock remained leader of the Labour Party.

In November 1990 following a contested leadership election, Margaret Thatcher resigned as leader of the Conservative Party and was succeeded as leader and Prime Minister by John Major. Most opinion polls had shown Labour comfortably ahead of the Tories for more than a year before Thatcher's resignation, with the fall in Tory support blamed largely on her introduction of the unpopular poll tax, combined with the fact that the economy was sliding into recession at the time.

The change of leader in the Tory government saw a turnaround in support for the Tories, who regularly topped the opinion polls throughout 1991 although Labour regained the lead more than once.

The "yo-yo" in the opinion polls continued into 1992, though after November 1990 any Labour lead in the polls was rarely sufficient for a majority. Major resisted Kinnock's calls for a general election throughout 1991. Kinnock campaigned on the theme "It's Time for a Change", urging voters to elect a new government after more than a decade of unbroken Conservative rule. However, the Conservatives themselves had undergone a change of leader from Thatcher to Major, and replaced the Community Charge. From the outset, it was clearly a well-received change, as Labour's 14-point lead in the November 1990 "Poll of Polls" was replaced by an 8% Tory lead a month later.

The 1992 general election was widely tipped to result in a hung parliament or a narrow Labour majority, but in the event the Conservatives were returned to power, though with a much reduced majority of 21. Despite the increased number of seats and votes, it was still an incredibly disappointing result for supporters of the Labour party. For the first time in over 30 years there was serious doubt among the public and the media as to whether Labour could ever return to government.

Kinnock then resigned as leader and was succeeded by John Smith. Once again the battle erupted between the old guard on the party's left and those identified as "modernisers". The old guard argued that trends showed they were regaining strength under Smith's strong leadership. Meanwhile, the breakaway SDP merged with the Liberal Party. The new Liberal Democrats seemed to pose a major threat to the Labour base. Tony Blair (the Shadow Home Secretary) had an entirely different vision. Blair, the leader of the "modernising" faction (Blairites), argued that the long-term trends had to be reversed, arguing that the party was too locked into a base that was shrinking, since it was based on the working-class, on trade unions, and on residents of subsidised council housing. Blairites argued that the rapidly growing middle class was largely ignored, as well as more ambitious working-class families. It was said that they aspired to become middle-class, but accepted the Conservative argument that Labour was holding ambitious people back, with its levelling down policies. They increasingly saw Labour in a negative light, regarding higher taxes and higher interest rates. To present a fresh face and new policies to the electorate, New Labour needed more than fresh leaders; it had to jettison outdated policies, argued the modernisers. The first step was procedural, but essential. Calling on the slogan, "One Member, One Vote" Blair (with some help from Smith) defeated the union element and ended block voting by leaders of labour unions. Blair and the modernisers called for radical adjustment of Party goals by repealing "Clause IV", the historic commitment to nationalisation of industry. This was achieved in 1995.

Black Wednesday in September 1992 damaged the Conservative government's reputation for economic competence, and by the end of that year Labour had a comfortable lead over the Tories in the opinion polls. Although the recession was declared over in April 1993 and a period of strong and sustained economic growth followed, coupled with a relatively swift fall in unemployment, the Labour lead in the opinion polls remained strong. However, Smith died from a heart attack in May 1994.

New Labour, 1994–2010

Further information: New Labour, Premiership of Tony Blair, Premiership of Gordon Brown, Blair ministry, and Brown ministry Tony Blair, Prime Minister, 1997–2007

Tony Blair, Prime Minister, 1997–2007 Gordon Brown, Prime Minister, 2007–2010

Gordon Brown, Prime Minister, 2007–2010

Tony Blair continued to move the party further to the centre, abandoning the largely symbolic Clause Four at the 1995 mini-conference in a strategy to increase the party's appeal to "middle England". More than a simple re-branding, however, the project would draw upon the Third Way strategy, informed by the thoughts of the British sociologist Anthony Giddens.

New Labour was first termed as an alternative branding for the Labour Party, dating from a conference slogan first used by the Labour Party in 1994, which was later seen in a draft manifesto published by the party in 1996, called New Labour, New Life For Britain. It was a continuation of the trend that had begun under the leadership of Neil Kinnock. New Labour as a name has no official status, but remains in common use to distinguish modernisers from those holding to more traditional positions, normally referred to as "Old Labour".

New Labour is a party of ideas and ideals but not of outdated ideology. What counts is what works. The objectives are radical. The means will be modern.

The Labour Party won the 1997 general election with a landslide majority of 179; it was the largest Labour majority ever, and at the time the largest swing to a political party achieved since 1945. Over the next decade, a wide range of progressive social reforms were enacted, with millions lifted out of poverty during Labour's time in office largely as a result of various tax and benefit reforms.

Among the early acts of Blair's government were the establishment of the national minimum wage, the devolution of power to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, major changes to the regulation of the banking system, and the re-creation of a citywide government body for London, the Greater London Authority, with its own elected-Mayor.

Combined with a Conservative opposition that had yet to organise effectively under William Hague, and the continuing popularity of Blair, Labour went on to win the 2001 election with a similar majority, dubbed the "quiet landslide" by the media. In 2003 Labour introduced tax credits, government top-ups to the pay of low-wage workers.

A perceived turning point was when Blair controversially allied himself with US President George W. Bush in supporting the Iraq War, which caused him to lose much of his political support. The UN Secretary-General, among many, considered the war illegal and a violation of the UN Charter. The Iraq War was deeply unpopular in most western countries, with Western governments divided in their support and under pressure from worldwide popular protests. The decisions that led up to the Iraq war and its subsequent conduct were the subject of Sir John Chilcot's Iraq Inquiry (commonly referred to as the "Chilcot report").

In the 2005 general election, Labour was re-elected for a third term, but with a reduced majority of 66 and popular vote of only 35.2%, the lowest percentage of any majority government in British history. During this election, proposed controversial posters by Alastair Campbell where opposition leader Michael Howard and shadow chancellor Oliver Letwin, who are both Jewish, were depicted as flying pigs were criticised as being anti-Semitic. The posters were referring to the expression 'when pigs fly', to suggest that Tory election promises were unrealistic. In response, Campbell said that the posters were not in "any way shape or form" intended to be anti-Semitic.

Blair announced in September 2006 that he would quit as leader within the year, though he had been under pressure to quit earlier than May 2007 in order to get a new leader in place before the May elections which were expected to be disastrous for Labour. In the event, the party did lose power in Scotland to a minority Scottish National Party government at the 2007 elections and, shortly after this, Blair resigned as Prime Minister and was replaced by his Chancellor, Gordon Brown. Although the party experienced a brief rise in the polls after this, its popularity soon slumped to its lowest level since the days of Michael Foot. During May 2008, Labour suffered heavy defeats in the London mayoral election, local elections and the loss in the Crewe and Nantwich by-election, culminating in the party registering its worst ever opinion poll result since records began in 1943, of 23%, with many citing Brown's leadership as a key factor. Membership of the party also reached a low ebb, falling to 156,205 by the end of 2009: over 40 per cent of the 405,000 peak reached in 1997 and thought to be the lowest total since the party was founded.

Finance proved a major problem for the Labour Party during this period; a "cash for peerages" scandal under Blair resulted in the drying up of many major sources of donations. Declining party membership, partially due to the reduction of activists' influence upon policy-making under the reforms of Neil Kinnock and Blair, also contributed to financial problems. Between January and March 2008, the Labour Party received just over £3 million in donations and were £17 million in debt; compared to the Conservatives' £6 million in donations and £12 million in debt. These debts eventually mounted to £24.5 million, and were finally fully repaid in 2015.

In the 2010 general election on 6 May that year, Labour with 29.0% of the vote won the second largest number of seats (258). The Conservatives with 36.5% of the vote won the largest number of seats (307), but no party had an overall majority, meaning that Labour could still remain in power if they managed to form a coalition with at least one smaller party. However, the Labour Party would have had to form a coalition with more than one other smaller party to gain an overall majority; anything less would result in a minority government. On 10 May 2010, after talks to form a coalition with the Liberal Democrats broke down, Brown announced his intention to stand down as Leader before the Labour Party Conference but a day later resigned as both Prime Minister and party leader.

Opposition: Miliband, 2010–2015

Harriet Harman became the Leader of the Opposition and acting Leader of the Labour Party following the resignation of Gordon Brown on 11 May 2010, pending a leadership election subsequently won by Ed Miliband. Miliband emphasised "responsible capitalism" and greater state intervention to change the balance of the economy away from financial services. Tackling vested interests and opening up closed circles in British society were themes he returned to a number of times. Miliband also argued for greater regulation of banks and energy companies.

The Parliamentary Labour Party voted to abolish Shadow Cabinet elections in 2011, ratified by the National Executive Committee and Party Conference. Henceforth the leader of the party chose the Shadow Cabinet members.

The party's performance held up in local elections in 2012 with Labour consolidating its position in the North and Midlands, while also regaining some ground in Southern England. In Wales the party enjoyed good successes, regaining control of most Welsh councils lost in 2008, including Cardiff. In Scotland, Labour held overall control of Glasgow City Council despite some predictions to the contrary, and also enjoyed a +3.26 swing across Scotland. Results in London were mixed: Ken Livingstone lost the election for Mayor of London, but the party gained its highest ever representation in the Greater London Authority in the concurrent assembly election.

On 1 March 2014, at a special conference the party reformed internal Labour election procedures, including replacing the electoral college system for selecting new leaders with a "one member, one vote" system following the recommendation of a review by former general-secretary Ray Collins. Mass membership would be encouraged by allowing "registered supporters" to join at a low cost, as well as full membership. Members from the trade unions would also have to explicitly "opt in" rather than "opt out" of paying a political levy to Labour.

The party edged out the Conservatives in the May 2014 European parliamentary elections winning 20 seats to the Conservatives' 19. However the UK Independence Party won 24 seats. Labour also gained 324 councillors in the 2014 local elections.

In September 2014, Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls outlined his plans to cut the government's current account deficit, and the party carried these plans into the 2015 general election. Whereas Conservatives campaigned for a surplus on all government spending, including investment, by 2018–19, Labour stated it would balance the budget, excluding investment, by 2020.

The 2015 general election unexpectedly resulted in a net loss of seats, with Labour representation falling to 232 seats in the House of Commons. The party lost 40 of its 41 seats in Scotland in the face of record swings to the Scottish National Party. Though Labour gained more than 20 seats in England and Wales, mostly from the Liberal Democrats but also from the Conservative Party, it lost more seats to the Conservatives, including Ed Balls in Morley and Outwood, for net losses overall.

Opposition: Corbyn, 2015–present

See also: Labour Party leadership of Jeremy Corbyn

After the 2015 election, Miliband resigned as party leader and Harriet Harman again became acting leader. Labour held a leadership election, in which Jeremy Corbyn, then a member of the Socialist Campaign Group, was considered a fringe hopeful when the contest began, receiving nominations from just 36 MPs, one more than the minimum required to stand, and the support of just 16 MPs. However, he benefited from a large influx of new members as well as new affiliated and registered supporters introduced under Miliband. He was elected leader with 60% of the vote and membership numbers continued to climb after the start of Corbyn's leadership.

Tensions soon developed in the parliamentary party over Corbyn's leadership. Following the referendum on EU membership more than two dozen members of the Shadow Cabinet resigned in late June 2016, and a no-confidence vote was supported by 172 MPs against 40 supporting Corbyn. In July 2016, a leadership election was called as Angela Eagle launched a challenge against Corbyn. She was soon joined by rival challenger Owen Smith, prompting Eagle to withdraw in order to ensure there was only one challenger on the ballot. In September 2016 Corbyn retained leadership of the party with an increased share of the vote. By the end of the contest Labour's membership had grown to more than 500,000, making it the largest political party in terms of membership in Western Europe.

Following the party's decision to support the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill 2017, at least three shadow cabinet ministers, all representing constituencies which voted to remain in the EU, resigned from their position as a result of the party's decision to invoke Article 50 under the bill. 47 of 229 Labour MPs voted against the bill (in defiance of the party's three-line whip). Unusually, the rebel frontbenchers did not face immediate dismissal. According to the New Statesman, approximately 7,000 members of the Labour Party also resigned in protest over the party's stance; this number has been confirmed by senior Labour sources.

In April 2017, the Prime Minister Theresa May announced she would seek an unexpected snap election in June 2017. Corbyn said he welcomed May's proposal and said his party would support the government's move in the parliamentary vote. The necessary super-majority of two-thirds was achieved when 522 of the 650 Members of Parliament voted in support.

In May 2017 Loughborough University's Centre for Research in Communication and Culture considered a majority of media reports on Labour to be critical compared to coverage of the Conservatives. The Daily Mail and Daily Express praised Theresa May for election pledges that were condemned when proposed by Labour in previous elections.

Some of the opinion polls had shown a 20-point Conservative lead over Labour before the election was called, but this lead had narrowed by the day of the 2017 general election, which resulted in a hung parliament. Despite remaining in opposition for its third election in a row, Labour at 40.0% won its greatest share of the vote since 2001, made a net gain of 30 seats to reach 262 total MPs, and, with a swing of 9.6%, achieved the biggest percentage-point increase in its vote share in a single general election since 1945. Immediately following the election party membership rose by 35,000. In July 2017 opinion polling suggested Labour led the Conservatives, 45% to 39% while a YouGov poll gave Labour an 8-point lead over the Conservatives.

Allegations of antisemitism in Labour have been made, particularly after comments in 2016 by Naz Shah and Ken Livingstone resulted in their suspension pending investigation. The resulting criticism prompted the Party to establish the Chakrabarti Inquiry. Some party members were expelled for bringing the party into disrepute while Livingstone resigned from it in 2018 after being suspended for two years. The party made antisemitism and other forms of hate speech a disciplinary offence in 2017, and in 2018 Jennie Formby was appointed General Secretary of the Labour Party where she began the reorganisation and expansion of Labour's disciplinary structures, leading to further and continuing expulsions, resignations and other sanctions. In 2019, training in antisemitism was organised for staff and members with responsibility for disciplinary processes. In February 2019, Formby released statistics of antisemitism cases between April 2018 and January 2019 that showed 0.1% of Party members had been investigated over antisemitism allegations. Several MPs and peers left the Party that year, most of whom formed The Independent Group, citing both the party's handling of Brexit and antisemitism. In July 2019, the Party announced further changes to disciplinary processes and issued educational materials on the subject.

Ideology

The Labour Party is considered to be left of centre. It was initially formed as a means for the trade union movement to establish political representation for itself at Westminster. It only gained a "socialist" commitment with the original party constitution of 1918. That "socialist" element, the original Clause IV, was seen by its strongest advocates as a straightforward commitment to the "common ownership", or nationalisation, of the "means of production, distribution and exchange". Although about a third of British industry was taken into public ownership after the Second World War, and remained so until the 1980s, the right of the party were questioning the validity of expanding on this objective by the late 1950s. Influenced by Anthony Crosland's book, The Future of Socialism (1956), the circle around party leader Hugh Gaitskell felt that the commitment was no longer necessary. While an attempt to remove Clause IV from the party constitution in 1959 failed, Tony Blair, and the "modernisers" saw the issue as putting off potential voters, and were successful thirty-five years later, with only limited opposition from senior figures in the party.

Clause IV (1995)Party Constitution, Labour Party Rule BookThe Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many, not the few, where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe, and where we live together, freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect.

Party electoral manifestos have not contained the term socialism since 1992. The new version of Clause IV, though affirming a commitment to democratic socialism, no longer definitely commits the party to public ownership of industry: in its place it advocates "the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition" along with "high quality public services ... either owned by the public or accountable to them".

Historically, influenced by Keynesian economics, the party favoured government intervention in the economy, and the redistribution of wealth. Taxation was seen as a means to achieve a "major redistribution of wealth and income" in the October 1974 election manifesto. The party also desired increased rights for workers, and a welfare state including publicly funded healthcare.

From the late-1980s onwards, the party adopted free market policies, leading many observers to describe the Labour Party as social democratic or the Third Way, rather than democratic socialist. Other commentators go further and argue that traditional social democratic parties across Europe, including the British Labour Party, have been so deeply transformed in recent years that it is no longer possible to describe them ideologically as "social democratic", and claim that this ideological shift has put new strains on the Labour Party's traditional relationship with the trade unions. Historically within the party, differentiation was made between the social democratic and the socialist wings of the party, the latter often subscribed to a radical socialist, even Marxist, ideology.

In more recent times, a limited number of Members of Parliament in the Socialist Campaign Group and the Labour Representation Committee have seen themselves as the standard bearers for the radical socialist tradition in contrast to the democratic socialist tradition represented by organisations such as Compass and the magazine Tribune. The group Progress, founded in 1996, represents the centrist/Blairite position in the party and is opposed to the Corbyn leadership.

In 2015, Momentum was created by Jon Lansman as a grass-roots left-wing organisation following Jeremy Corbyn's election as party leader. Rather than organising among the PLP, Momentum is a rank and file grouping with an estimated 40,000 members.

Symbols

Labour has long been identified with red, a political colour traditionally affiliated with socialism and the labour movement. Prior to the red flag logo, the party had used a modified version of the classic 1924 shovel, torch, and quill emblem. In 1924 a brand conscious Labour leadership had devised a competition, inviting supporters to design a logo to replace the 'polo mint' like motif that had previously appeared on party literature. The winning entry, emblazoned with the word "Liberty" over a design incorporating a torch, shovel and quill symbol, was popularised through its sale, in badge form, for a shilling. The party conference in 1931 passed a motion "That this conference adopts Party Colours, which should be uniform throughout the country, colours to be red and gold". Since the party's inception, the red flag has been Labour's official symbol; the flag has been associated with socialism and revolution ever since the 1789 French Revolution and the revolutions of 1848. The red rose, a symbol of socialism and social democracy, was adopted as the party symbol in 1986 as part of a rebranding exercise and is now incorporated into the party logo.

The red flag became an inspiration which resulted in the composition of "The Red Flag", the official party anthem since its inception, being sung at the end of party conferences and on various occasions such as in Parliament on February 2006 to mark the centenary of the Labour Party's founding. During New Labour attempts were made to play down the role of the song, however it still remains in use. The patriotic song Jerusalem, based on a William Blake poem, is also frequently sung.

Constitution and structure

The Labour Party is a membership organisation consisting of individual members and constituency Labour parties, affiliated trade unions, socialist societies and the Co-operative Party, with which it has an electoral agreement. Members who are elected to parliamentary positions take part in the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) and European Parliamentary Labour Party (EPLP).

The party's decision-making bodies on a national level formally include the National Executive Committee (NEC), Labour Party Conference and National Policy Forum (NPF)—although in practice the Parliamentary leadership has the final say on policy. The 2008 Labour Party Conference was the first at which affiliated trade unions and Constituency Labour Parties did not have the right to submit motions on contemporary issues that would previously have been debated. Labour Party conferences now include more "keynote" addresses, guest speakers and question-and-answer sessions, while specific discussion of policy now takes place in the National Policy Forum.

The Labour Party is an unincorporated association without a separate legal personality, and the Labour Party Rule Book legally regulates the organisation and the relationship with members. The General Secretary represents the party on behalf of the other members of the Labour Party in any legal matters or actions.

Membership and registered supporters

In August 2015, prior to the 2015 leadership election, the Labour Party reported 292,505 full members, 147,134 affiliated supporters (mostly from affiliated trade unions and socialist societies) and 110,827 registered supporters; a total of about 550,000 members and supporters. As of December 2017, the party had approximately 552,000 full members, making it the largest political party in Western Europe. Consequently, membership fees became the largest component of the party's income, overtaking trade unions donations which were previously of most financial importance, and in 2017 making Labour the most financially well-off British political party.

In February 2019, leaked membership figures revealed a decline to 512,000. By July 2019, further leaked figures suggested the membership may have fallen to 485,000.

For many years Labour held to a policy of not allowing residents of Northern Ireland to apply for membership, instead supporting the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) which informally takes the Labour whip in the House of Commons. The 2003 Labour Party Conference accepted legal advice that the party could not continue to prohibit residents of the province joining, and whilst the National Executive has established a regional constituency party it has not yet agreed to contest elections there. In December 2015 a meeting of the members of the Labour Party in Northern Ireland decided unanimously to contest the elections for the Northern Ireland Assembly held in May 2016.

Trade union link

See also: Trade unionism in the United Kingdom

The Trade Union and Labour Party Liaison Organisation is the co-ordinating structure that supports the policy and campaign activities of affiliated union members within the Labour Party at the national, regional and local level.

As it was founded by the unions to represent the interests of working-class people, Labour's link with the unions has always been a defining characteristic of the party. In recent years this link has come under increasing strain, with the RMT being expelled from the party in 2004 for allowing its branches in Scotland to affiliate to the left-wing Scottish Socialist Party. Other unions have also faced calls from members to reduce financial support for the Party and seek more effective political representation for their views on privatisation, public spending cuts and the anti-trade union laws. Unison and GMB have both threatened to withdraw funding from constituency MPs and Dave Prentis of UNISON has warned that the union will write "no more blank cheques" and is dissatisfied with "feeding the hand that bites us". Union funding was redesigned in 2013 after the Falkirk candidate-selection controversy. The Fire Brigades Union, which "severed links" with Labour in 2004, re-joined the party under Corbyn's leadership in 2015.

European and international affiliation

The Labour Party is a founder member of the Party of European Socialists (PES). The European Parliamentary Labour Party's 20 MEPs are part of the Socialists and Democrats (S&D), the second largest group in the European Parliament. The Labour Party is represented by Emma Reynolds in the PES Presidency.

The party was a member of the Labour and Socialist International between 1923 and 1940. Since 1951 the party has been a member of the Socialist International, which was founded thanks to the efforts of the Clement Attlee leadership. However, in February 2013, the Labour Party NEC decided to downgrade participation to observer membership status, "in view of ethical concerns, and to develop international co-operation through new networks". Labour was a founding member of the Progressive Alliance international founded in co-operation with the Social Democratic Party of Germany and other social-democratic parties on 22 May 2013.

Electoral performance

UK wide elections

UK General Elections

See also: Elections in the United Kingdom § General elections| Election | Leader | Votes | Seats | Position | Resulting government | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | ± | ||||

| 1900 | Keir Hardie | 62,698 | 1.8 | 2 / 670 | 5th | Conservative–Liberal Unionist | |

| 1906 | 321,663 | 5.7 | 29 / 670 | Liberal | |||

| Jan-1910 | Arthur Henderson | 505,657 | 7.6 | 40 / 670 | Liberal minority | ||

| Dec-1910 | George Nicoll Barnes | 371,802 | 7.1 | 42 / 670 | Liberal minority | ||

| 1918 | William Adamson | 2,245,777 | 21.5 | 57 / 707 | Liberal–Conservative | ||

| 1922 | J. R. Clynes | 4,076,665 | 29.7 | 142 / 615 | Conservative | ||

| 1923 | Ramsay MacDonald | 4,267,831 | 30.7 | 191 / 625 | Labour minority | ||

| 1924 | 5,281,626 | 33.3 | 151 / 615 | Conservative | |||

| 1929 | 8,048,968 | 37.1 | 287 / 615 | Labour minority | |||

| 1931 | Arthur Henderson | 6,339,306 | 30.8 | 52 / 615 | National Labour-Conservative–Liberal | ||

| 1935 | Clement Attlee | 7,984,988 | 38.0 | 154 / 615 | Conservative–National Labour–Liberal National | ||

| 1945 | 11,967,746 | 47.7 | 393 / 640 | Labour | |||

| 1950 | 13,266,176 | 46.1 | 315 / 625 | Labour | |||

| 1951 | 13,948,883 | 48.8 | 295 / 625 | Conservative | |||

| 1955 | 12,405,254 | 46.4 | 277 / 630 | Conservative | |||

| 1959 | Hugh Gaitskell | 12,216,172 | 43.8 | 258 / 630 | Conservative | ||

| 1964 | Harold Wilson | 12,205,808 | 44.1 | 317 / 630 | Labour | ||

| 1966 | 13,096,629 | 48.0 | 364 / 630 | Labour | |||

| 1970 | 12,208,758 | 43.1 | 288 / 630 | Conservative | |||

| Feb-1974 | 11,645,616 | 37.2 | 301 / 635 | Labour minority | |||

| Oct-1974 | 11,457,079 | 39.2 | 319 / 635 | Labour | |||

| 1979 | James Callaghan | 11,532,218 | 36.9 | 269 / 635 | Conservative | ||

| 1983 | Michael Foot | 8,456,934 | 27.6 | 209 / 650 | Conservative | ||

| 1987 | Neil Kinnock | 10,029,807 | 30.8 | 229 / 650 | Conservative | ||

| 1992 | 11,560,484 | 34.4 | 271 / 651 | Conservative | |||

| 1997 | Tony Blair | 13,518,167 | 43.2 | 419 / 659 | Labour | ||

| 2001 | 10,724,953 | 40.7 | 413 / 659 | Labour | |||

| 2005 | 9,562,122 | 35.3 | 356 / 646 | Labour | |||

| 2010 | Gordon Brown | 8,601,441 | 29.1 | 258 / 650 | Conservative–Lib Dem | ||

| 2015 | Ed Miliband | 9,339,818 | 30.5 | 232 / 650 | Conservative | ||

| 2017 | Jeremy Corbyn | 12,874,985 | 40.0 | 262 / 650 | Conservative minority with DUP confidence & supply | ||

| Current | 244 / 650 | Conservative minority with DUP confidence & supply | |||||

- Note

- The first election held under the Representation of the People Act 1918 in which all men over 21, and most women over the age of 30 could vote, and therefore a much larger electorate.

- The first election held under the Representation of the People Act 1928 which gave all women aged over 21 the vote.

- Franchise extended to all 18- to 20-year-olds under the Representation of the People Act 1969.

European Parliament elections

See also: European Parliament and Elections to the European ParliamentElections to the European Parliament began in 1979, and were held under the first past the post system until 1999, when a form of proportional representation was introduced.

| Year | Leader | Share of votes | Seats | Change | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | James Callaghan | 31.6 | 17 / 78 | 2nd | |

| 1984 | Neil Kinnock | 34.7 | 32 / 78 | ||

| 1989 | 40.1 | 45 / 78 | |||

| 1994 | Margaret Beckett (interim) |

42.6 | 62 / 84 | ||

| 1999 | Tony Blair | 28.0 | 29 / 84 | ||

| 2004 | 22.6 | 19 / 78 | |||

| 2009 | Gordon Brown | 15.7 | 13 / 72 | ||

| 2014 | Ed Miliband | 24.4 | 20 / 73 | ||

| 2019 | Jeremy Corbyn | 13.6 | 10 / 73 |

- Note

- Electoral system changed from first past the post to proportional representation.

Devolved assembly elections

Scottish Parliament elections

See also: Scottish Parliament and Scottish Labour Party| Year | Leader | Share of votes (constituency) |

Share of votes (list) |

Seats | Change | Position | Resulting government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Donald Dewar | 38.8% | 33.6% | 56 / 129 | 1st | Labour–Lib Dem | |

| 2003 | Jack McConnell | 34.6% | 29.3% | 50 / 129 | Labour–Lib Dem | ||

| 2007 | 32.2% | 29.2% | 46 / 129 | SNP minority | |||

| 2011 | Iain Gray | 31.7% | 26.3% | 37 / 129 | SNP | ||

| 2016 | Kezia Dugdale | 22.6% | 19.1% | 24 / 129 | SNP minority |

Welsh Assembly elections

See also: National Assembly for Wales and Welsh Labour| Year | Leader | Share of vote (constituency) |

Share of vote (list) |

Seats won | Change | Position | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Alun Michael | 37.6% | 35.5% | 28 / 60 | 1st | Labour-Lib Dem | |

| 2003 | Rhodri Morgan | 40% | 36.6% | 30 / 60 | Labour | ||

| 2007 | 32.2% | 29.7% | 26 / 60 | Labour-Plaid Cymru | |||

| 2011 | Carwyn Jones | 42.3% | 36.9% | 30 / 60 | Labour | ||

| 2016 | 34.7% | 31.5% | 29 / 60 | Labour minority |

London Assembly and Mayoral elections

See also: London Assembly and London Labour Party| Year | Share of votes (constituency) |

Share of votes (list) |

Seats | Change | Position | Mayoralty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 31.6 | 30.3 | 9 / 25 | 1st | ||

| 2004 | 24.7 | 25.0 | 7 / 25 | |||

| 2008 | 28.0 | 27.1 | 8 / 25 | |||

| 2012 | 42.3 | 41.1 | 12 / 25 | |||

| 2016 | 43.5 | 40.3 | 12 / 25 |

Combined authority elections

| Year | Leader | Mayoralties won | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Jeremy Corbyn | 2 / 6 | |

| 2018 | 1 / 1 | ||

| 2019 | 1 / 1 |

Leadership

Leaders of the Labour Party since 1906

Main article: Leader of the Labour Party (UK)- Keir Hardie, 1906–08

- Arthur Henderson, 1908–10

- George Nicoll Barnes, 1910–11

- Ramsay MacDonald, 1911–14

- Arthur Henderson, 1914–17

- William Adamson, 1917–21

- John Robert Clynes, 1921–22

- Ramsay MacDonald, 1922–31

- Arthur Henderson, 1931–32

- George Lansbury, 1932–35

- Clement Attlee, 1935–55

- Hugh Gaitskell, 1955–63

- George Brown, 1963 (acting)

- Harold Wilson, 1963–76

- James Callaghan, 1976–80

- Michael Foot, 1980–83

- Neil Kinnock, 1983–92

- John Smith, 1992–94

- Margaret Beckett, 1994 (acting)

- Tony Blair, 1994–2007

- Gordon Brown, 2007–2010

- Harriet Harman, 2010 (acting)

- Ed Miliband, 2010–2015

- Harriet Harman, 2015 (acting)

- Jeremy Corbyn, 2015–present

Living former Labour Party leaders

As of February 2017, there are six living former Labour Party leaders, as seen below.

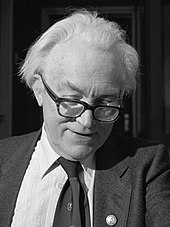

-

Neil Kinnock

Neil Kinnock

served 1983–1992

born 1942 (age 82) -

Margaret Beckett

Margaret Beckett

served 1994 (Interim)

born 1943 (age 81) -

Tony Blair

Tony Blair

served 1994–2007

born 1953 (age 71) -

Gordon Brown

Gordon Brown

served 2007–2010

born 1951 (age 73) -

Harriet Harman

Harriet Harman

served 2010 and 2015 (Interim)

born 1950 (age 74) -

Ed Miliband

Ed Miliband

served 2010–2015

born 1969 (age 55)

Deputy Leaders of the Labour Party since 1922

Main article: Deputy Leader of the Labour Party (UK)- John Robert Clynes, 1922–32

- William Graham, 1931–32

- Clement Attlee, 1932–35

- Arthur Greenwood, 1935–45

- Herbert Morrison, 1945–55

- Jim Griffiths, 1955–59

- Aneurin Bevan, 1959–60

- George Brown, 1960–70

- Roy Jenkins, 1970–72

- Edward Short, 1972–76

- Michael Foot, 1976–80

- Denis Healey, 1980–83

- Roy Hattersley, 1983–92

- Margaret Beckett, 1992–94

- John Prescott, 1994–2007

- Harriet Harman, 2007–15

- Tom Watson, 2015–present

Living former Labour Party deputy leaders

As of January 2025, there are four living former Labour Party deputy leaders, as seen below.

-

Roy Hattersley

Roy Hattersley

served 1983–1992

born 1932 (age 92) -

Margaret Beckett

Margaret Beckett

served 1992–1994

born 1943 (age 81) -

John Prescott

John Prescott

served 1994–2007

born 1938 (age 86) -

Harriet Harman

Harriet Harman

served 2007–2015

born 1950 (age 74)

Leaders in the House of Lords since 1924

- Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, 1924–28

- Charles Cripps, 1st Baron Parmoor, 1928–31

- Arthur Ponsonby, 1st Baron Ponsonby of Shulbrede, 1931–35

- Harry Snell, 1st Baron Snell, 1935–40

- Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison, 1940–52

- William Jowitt, 1st Earl Jowitt, 1952–55

- Albert Victor Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Hillsborough, 1955–64

- Frank Pakenham, 7th Earl of Longford, 1964–68

- Edward Shackleton, Baron Shackleton, 1968–74

- Malcolm Shepherd, 2nd Baron Shepherd, 1974–76

- Fred Peart, Baron Peart, 1976–82

- Cledwyn Hughes, Baron Cledwyn of Penrhos, 1982–92

- Ivor Richard, Baron Richard, 1992–98

- Margaret Jay, Baroness Jay of Paddington, 1998–2001

- Gareth Williams, Baron Williams of Mostyn, 2001–2003

- Valerie Amos, Baroness Amos, 2003–2007

- Catherine Ashton, Baroness Ashton of Upholland, 2007–2008

- Janet Royall, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon, 2008–2015

- Angela Smith, Baroness Smith of Basildon, 2015–present

Labour Prime Ministers

| Name | Portrait | Country of birth | Periods in office |

|---|---|---|---|

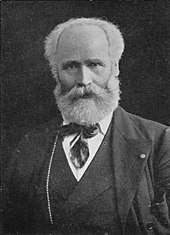

| Ramsay MacDonald |

|

Scotland | 1924; 1929–1931 (First and second MacDonald ministries) |

| Clement Attlee |

|

England | 1945–1950; 1950–1951 (Attlee ministry) |

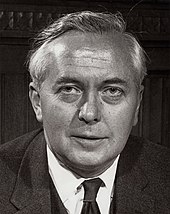

| Harold Wilson |

|

England | 1964–1966; 1966–1970; 1974; 1974–1976 (First and Second Wilson ministries) |

| James Callaghan |

|

England | 1976–1979 (Callaghan ministry) |

| Tony Blair |

|

Scotland | 1997–2001; 2001–2005; 2005–2007 (Blair ministry) |

| Gordon Brown |

|

Scotland | 2007–2010 (Brown ministry) |

See also

- Antisemitism in the Labour Party

- Blue Labour

- English Labour Network

- History of the Labour Party (UK)

- Labour Co-operative

- Labour In for Britain

- Labour Party in Northern Ireland

- Labour Representation Committee election results

- List of Labour Parties

- List of Labour Party (UK) MPs

- List of organisations associated with the British Labour Party

- List of UK Labour Party general election manifestos

- Politics of the United Kingdom

- Scottish Labour Party

- Socialist Labour Party (UK)

- Socialist Party (England and Wales)

- Welsh Labour

References

- Brivati & Heffernan 2000: "On 27 February 1900, the Labour Representation Committee was formed to campaign for the election of working class representatives to parliament."

- ^ Thorpe 2008, p. 8.

- Stephen O'Shea and James Buckley (8 December 2015). "Corbyn's Labour party set for swanky HQ move". CoStar. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- "Membership of UK political parties". House of Commons Library. UK Parliament. 9 August 2019.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2017). "United Kingdom". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Adams, Ian (1998). Ideology and Politics in Britain Today (illustrated, reprint ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-7190-5056-5. Retrieved 21 March 2015 – via Google Books.

- "Local Council Political Compositions". Open Council Data UK. 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Matthew Worley (2009). The Foundations of the British Labour Party: Identities, Cultures and Perspectives, 1900–39. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-7546-6731-5 – via Google Books.

- MacAskill, Ewen (27 September 2016). "Jeremy Corbyn's team targets Labour membership of 1 million". the Guardian.

- "BBC – History – The rise of the Labour Party (pictures, video, facts & news)".

- Martin Crick, The History of the Social-Democratic Federation

- p.131 The Foundations of the British Labour Party by Matthew Worley ISBN 9780754667315

- ‘The formation of the Labour Party – Lessons for today’ Archived 22 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Jim Mortimer, 2000; Jim Mortimer was a General Secretary of the Labour Party in the 1980s

- "Collection highlights". People's History Museum. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Wright & Carter 1997.

- ^ Thorpe 2001.

- "Collection Highlights, 1906 Labour Party minutes". People's History Museum. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- The Labour Party Archive Catalogue & Description, People's History Museum, archived from the original on 13 January 2015, retrieved 20 January 2015

- John Foster, "Strike action and working-class politics on Clydeside 1914–1919." International Review of Social History 35#1 (1990): 33–70.

- Bentley B. Gilbert, Britain since 1918 (1980) p 49.

- Rosemary Rees, Britain, 1890–1939 (2003), p. 200

- "Red Clydeside: The Communist Party and the Labour government [booklet cover] / Communist Party of Great Britain, 1924". Glasgow Digital Library. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Trevor Wilson, The downfall of the Liberal Party, 1914–1935 (1966) ch 14

- Thorpe 2001, pp. 51–53.

- Taylor 1965, pp. 213–214.

- Taylor 1965, pp. 219–220, 226–227.

- Charles Loch Mowat (1955). Britain Between the Wars, 1918–1940. Taylor & Francis. pp. 188–94.

- Pugh 2011, ch. 8.

- Winkler, Henry R. (1956). "The Emergence of a Labor Foreign Policy in Great Britain, 1918-1929". The Journal of Modern History. 28 (3): 247–258. doi:10.1086/237907. JSTOR 1876236.

- Kenneth E. Miller, Socialism and Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice in Britain to 1931 (1967) ch 4–7.

- John Shepherd, The Second Labour Government: A reappraisal (2012).

- Morgan, Kevin. (2006) MacDonald (20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century), Haus Publishing, ISBN 1-904950-61-2