This is an old revision of this page, as edited by UkrainianSavior1 (talk | contribs) at 06:57, 25 November 2019 (→Terminology). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 06:57, 25 November 2019 by UkrainianSavior1 (talk | contribs) (→Terminology)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Old East Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Region | Eastern Europe |

| Era | 10th–15th century |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | orv |

| Linguist List | orv |

| Glottolog | oldr1238 |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. | |

Old East Slavic also known as Old Belarusian, Old Ukrainian and Old Russian is the language, which according to some linguists was used during the 10th–15th centuries by East Slavs in Kievan Rus' and states which evolved in 13–15th centuries after the collapse of Kievan Rus'.

There is no consensus among linguists as to whether such a language as Old East Slavic existed at all, with some linguists arguing that there never was any Old East Slavic language and that all Slavic languages evolved from Proto-Slavic. According to some linguistic theories, Proto-Slavic spawned all Slavic languages, except the Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian languages, which they argue, evolved from Old East Slavic instead of directly from Proto-Slavic.

Terminology

Although the language is sometimes called "Old Russian" (Template:Lang-be, staražytnaruskaja mova; Template:Lang-ru, drevnerusskij jazyk; and Template:Lang-uk, davn’orus’ka mova), this term is something of a misnomer , because initial stages of the language which it denotes predate the dialectal divisions which mark the nascent distinction between modern East Slavic languages (Russian, Belorussian, and Ukrainian), and the language is "equally Old Belorussian and Old Ukrainian". Old East Slavic is therefore more appropriate term. Some scholars, such as Horace Lunt, also employ the term "Rusian" (with one "s") for the language, although this is the least commonly used form.

Main theories for and against existence of OES

According to some scholars, such as George Shevelov, Stepan Smal-Stotsky, Yevhen Tymchenko, Vsevolod Hantsov, Olena Kurylo, Ivan Ohienko etc., a common Old East Slavic language never existed at any time in the past, and Ukrainian, Belarusian and Russian languages emerged, like all other Slavic languages, directly from Proto-Slavic. According to this theory, the dialects of East Slavic tribes evolved gradually from the common Proto-Slavic language without any intermediate stages during the 6th through 9th centuries. This theory was supported by the results of George Shevelov's phonological studies.

According to original inventors of OES theory, such as Alexander Vostokov, Izmail Sreznevsky and Mikhail Lomonosov, Russian language (excluding Ukrainian or Belarusian, since Russians did not consider these languages as actual separate languages, but rather as dialects of Russian; Russian Academy of Science did not admit the existence of Ukrainian language until 1905) did not emerge from Proto-Slavic without any intermediate stages during the 6th through 9th centuries; instead, they argue that the Old East Slavic (OES) emerged in 10th–15th centuries and was spoken by East Slavs in Kievan Rus' and around 14–16th centuries it transformed into modern Russian. Later supporters of OES theory, who admitted that Ukrainian and Belarusian were in fact separate languages and were not dialects of Russian, argued that it was not just Russian language, but in fact Belarusian, Ukrainian and Russian that emerged around 14–16th centuries. According to these later supporters of OES theory, OES diverged into Belarusian and Ukrainian to the West, and Russian to the North-East, after the political boundaries of the Kievan Rus' were redrawn in the 14th century. During the time of the incorporation of the territories of modern Ukraine and Belarus into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Ukrainian and Belarusian diverged into identifiably separate languages.

General considerations of theory that argues the existence of OES

According to the proponents of the existence OES, it was a descendant of the Proto-Slavic language, with OES faithfully retaining many of its features. A striking innovation in the evolution of this language was the development of so-called pleophony (or polnoglasie 'full vocalisation'), which came to differentiate the newly evolving East Slavic from other Slavic dialects. For instance, Common Slavic *gordъ 'settlement, town' was reflected as OESl. gorodъ, Common Slavic *melko 'milk' > OESl. moloko, and Common Slavic *korva 'cow' > OESl korova. Other Slavic dialects are differed by resolving the closed-syllable clusters *eRC and *aRC as liquid metathesis (South Slavic and West Slavic), or by no change at all (see the article on Slavic liquid metathesis and pleophony for a detailed account).

Since extant written records of the language are sparse, it is difficult to assess the level of its unity. In consideration of the number of tribes and clans that constituted Kievan Rus, it is probable that there were many dialects of Old East Slavonic. Therefore, today we may speak definitively only of the languages of surviving manuscripts, which, according to some interpretations, show regional divergence from the beginning of the historical records. Nonetheless, by 1150 it had more unity than any other branch of Slavic, showing the fewest local variations.

With time, it evolved into several more diversified forms, which were the predecessors of the modern Belarusian, Russian, Rusyn and Ukrainian languages. The Russian split from Ukrainian came first, between 1200 and 1500, whereas separation of Russian and Belarusian took place by 1700. Each of these languages preserves much of the Old East Slavic grammar and vocabulary.

When after the end of the 'Tatar yoke' the territory of former Kievan Rus was divided between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the medieval Rus' principality Grand Principality of Moscow, two separate literary traditions emerged in these states, Ruthenian in the west and medieval Russian in the east.

Theorized OES literature

The Old East Slavic language developed a certain literature of its own, though most of it, except for the Book of Veles is, rather, Church Slavonic with pronounced East Slavic interference. Surviving literary monuments include the legal code Justice of the Rus (Руська правда /rus(ʲ)ka prau̯da/), a corpus of hagiography and homily, the epic Song of Igor (Слово о полку Игорєвѣ /slowo o pɔlku iɣorewi͡e/) and the earliest surviving manuscript of the Primary Chronicle (Повѣсть врємѧнныхъ лѣтъ /powi͡estʲ wremʲannɨx li͡et/) – the Laurentian codex (Лаврентьевский список /lau̯rentʲjew(ʲ)skɨj spisɔk/) of 1377.

The Book of Veles is the only surviving pre-Christian East Slavic literary monument which is written in Old East Slavic that's significantly different from Church Slavonic. It is said to have been found during the Russian civil war and to have disappeared in WWII. Since the account of its find and eventual fate (several photographs are claimed to survive) has not been confirmed, and its language deviates from the accepted reconstruction, most professional linguists have so far dismissed the book's authenticity. Prominent linguist George Shevelov considered it an elaborate fake.

The earliest dated specimen of something referred to as Old East Slavic literature by scholars (but would be better described as Church Slavonic with pronounced East Slavic interference) is Slovo o zakone i blagodati, by Hilarion, metropolitan of Kiev. In this work there is a panegyric on Prince Vladimir of Kiev, the hero of so much of East Slavic popular poetry. This subtle and graceful oration admirably conforms to the precepts of the Byzantine eloquence. It is rivalled by another panegyric on Vladimir, written a decade later by Yakov the Monk.

Other eleventh-century writers who wrote in Church Slavonic with pronounced East Slavic interference were Theodosius, a monk of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, who wrote Instructions on the Latin faith and other matters, and Luka Zhidiata, bishop of Novgorod, who has left us a curious Discourse to the Brethren. From the writings of Theodosius we see that many pagan habits were still in vogue among the people. He finds fault with them for allowing these to continue, and also for their drunkenness; nor do the monks escape his censures. Zhidiata writes in a more vernacular style than many of his contemporaries; he eschews the declamatory tone of the Byzantine authors. And here may be mentioned the many lives of the saints and the Fathers to be found in early East Slavic literature, starting with the two Lives of Sts Boris and Gleb, written in the late eleventh century and attributed to Jacob the Monk and to Nestor the Chronicler.

Another example of a book written in Church Slavonic with pronounced East Slavic interference is Primary Chronicle, also attributed to Nestor the Chronicler, which began the long series of similar annalists. There is a regular catena of similar chronicles, extending with only two breaks to the seventeenth century. Besides the work attributed to Nestor the Chronicler, we have chronicles of Novgorod, Kiev, Volhynia and many others. Every town of any importance could boast of its annalists, Pskov and Suzdal among others. In some respects these compilations, the productions of monks in their cloisters, remind us of Herodotus, dry details alternating with here and there a picturesque incident; and many of these annals abound with the quaintest stories.

In the twelfth century we have the sermons of bishop Cyril of Turov, which are attempts to imitate in Old East Slavic the florid Byzantine style. In his sermon on Holy Week, Christianity is represented under the form of spring, Paganism and Judaism under that of winter, and evil thoughts are spoken of as boisterous winds.

There are also admirable works of early travellers, as the igumen Daniel, who visited the Holy Land at the end of the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth century. A later traveller was Afanasiy Nikitin, a merchant of Tver, who visited India in 1470. He has left a record of his adventures, which has been translated into English and published for the Hakluyt Society.

A curious monument of old Slavonic times is the Pouchenie (Instruction), written by Vladimir Monomakh for the benefit of his sons. This composition is generally found inserted in the Chronicle of Nestor; it gives a fine picture of the daily life of a Slavonic prince. The Paterik of the Kievan Caves Monastery is a typical medieval collection of stories from the life of monks, featuring devils, angels, ghosts, and miraculous resurrections.

We now come to the famous Lay of Igor's Campaign, which narrates the expedition of Igor Svyatoslavich, prince of Novhorod-Siverskyi against the Cumans. It is neither epic nor a poem but is written in rhythmic prose. An interesting aspect of the text is its mix of Christianity and ancient Slavic religion. Igor's wife Yaroslavna famously invokes natural forces from the walls of Putyvl. Christian motifs present along with depersonalised pagan gods in the form of artistic images. Another aspect, which sets the book apart from contemporary Western epics, are its numerous and vivid descriptions of nature, and the role which nature plays in human lives. Of the whole bulk of the Old East Slavic literature, the Lay is the only work familiar to every educated Russian or Ukrainian. Its brooding flow of images, murky metaphors, and ever changing rhythm haven't been successfully rendered into English yet. Indeed, the meanings of many words found in it have not been satisfactorily explained by scholars.

The Zadonshchina is a sort of prose poem much in the style of the Tale of Igor's Campaign, and the resemblance of the latter to this piece furnishes an additional proof of its genuineness. This account of the battle of Kulikovo, which was gained by Dmitri Donskoi over the Mongols in 1380, has come down in three important versions.

The early laws of Rus’ present many features of interest, such as the Russkaya Pravda of Yaroslav the Wise, which is preserved in the chronicle of Novgorod; the date is between 1018 and 1072. The laws show Rus at that time to have been in civilization quite on a level with the rest of Europe.

Examples of books supposedly written in OES

The political unification of the region into the state called Kievan Rus', from which modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine trace their origins, occurred approximately a century before the adoption of Christianity in 988 and the establishment of the South Slavic Old Church Slavonic as the liturgical and literary language. The Old Church Slavonic language was introduced. Documentation of the language of this period is scanty, making it difficult at best fully to determine the relationship between the literary language and its spoken dialects.

There are references in Arab and Byzantine sources to pre-Christian Slavs in European Russia using some form of writing. Despite some suggestive archaeological finds and a corroboration by the tenth-century monk Chernorizets Hrabar that ancient Slavs wrote in "strokes and incisions", the exact nature of this system is unknown.

Although the Glagolitic alphabet was briefly introduced, as witnessed by church inscriptions in Novgorod, it was soon entirely superseded by the Cyrillic. The samples of birch-bark writing excavated in Novgorod have provided crucial information about the pure tenth-century vernacular in North-West Russia, almost entirely free of Church Slavonic influence. It is also known that borrowings and calques from Byzantine Greek began to enter the vernacular at this time, and that simultaneously the literary language in its turn began to be modified towards Eastern Slavic.

The following excerpts illustrate two of the most famous literary monuments.

NOTE:. The spelling of the original excerpt has been partly modernized. The translations are best attempts at being literal, not literary.

Primary Chronicle

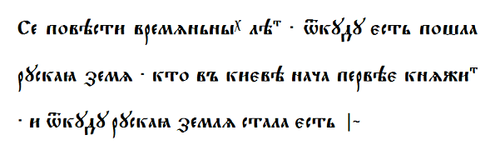

Further information: Primary Chroniclec. 1110, from the Laurentian Codex, 1377:

| Original | Се повѣсти времѧньны лѣ ‧ ѿкꙋдꙋ єсть пошла рꙋскаꙗ земѧ ‧ кто въ києвѣ нача первѣє кнѧжи ‧ и ѿкꙋдꙋ рꙋскаꙗ землѧ стала єсть |~ |

|---|---|

| Russian | Это повести прошлых лет, откуда пошла русская земля, кто в Киеве начал первым княжить, и откуда русская земля стала быть . |

| Ukrainian | Це повісті минулих літ, звідки пішла Руська земля, хто в Києві почав перший княжити, і звідки Руська земля стала бути. |

| Belarusian | Вось аповесці мінулых гадоў: адкуль пайшла руская зямля, хто ў Кіеве першым пачаў княжыць, і адкуль руская зямля паўстала. |

| English | These are the narratives of bygone years regarding the origin of the land of Rus', the first princes of Kiev, and from what source the land of Rus' had its beginning. |

Early language; fall of the yers in progress or arguably complete (several words end with a consonant; кнѧжит "to rule" < кънѧжити, modern Uk княжити, R княжить, B княжыць). South Slavic features include времѧньнъıх "bygone"; modern R прошлых, modern Ukr минулих, modern B мінулых. Correct use of perfect and aorist: єсть пошла "is/has come" (modern R пошла), нача "began" (modern R начал as a development of the old perfect.) Note the style of punctuation.

Tale of Igor's Campaign

Further information: Tale of Igor's CampaignСлово о пълку Игоревѣ. c. 1200, from the Pskov manuscript, fifteenth cent.

| Original | Не лѣпо ли ны бяшетъ братїє, начяти старыми словесы трудныхъ повѣстїй о пълку Игоревѣ, Игоря Святъславлича? Начати же ся тъй пѣсни по былинамъ сего времени, а не по замышленїю Бояню. Боянъ бо вѣщїй, аще кому хотяше пѣснь творити, то растѣкашется мыслію по древу, сѣрымъ вълкомъ по земли, шизымъ орломъ подъ облакы. |

|---|---|

| Transliteration | Ne lěpo li ny biašetŭ bratije, načiati starymi slovesy trudnyxŭ pověstij o pŭlku Igorevě, Igoria Sviatŭslaviča? Načati že sia tŭj pěsni po bylinamŭ sego vremeni, a ne po zamyšleniju Bojaniu. Bojanŭ bo věščij, ašče komu xotiaše pěsnĭ tvoriti, to rastěkašetsia mysliju po drevu, sěrymŭ vŭlkomŭ po zemli, šizymŭ orlomŭ podŭ oblaky. |

| English | Would it not be meet, o brothers, for us to begin with the old words the martial telling of the host of Igor, Igor Sviatoslavich? And to begin in the way of the true tales of this time, and not in the way of Bojan's inventions. For the wise Bojan, if he wished to devote to someone song, would fly in thought in the trees, like a grey wolf over land, like a bluish eagle beneath the clouds. |

Illustrates the sung epics, with typical use of metaphor and simile.

It has been suggested that the phrase растекаться мыслью по древу (to run in thought upon/over wood), which has become proverbial in modern Russian with the meaning "to speak ornately, at length, excessively," is a misreading of an original мысію (akin to мышь "mouse") from "run like a squirrel/mouse on a tree"; however, the reading мыслью is present in both the manuscript copy of 1790 and the first edition of 1800, and in all subsequent scholarly editions.

Other Notable examples of books supposedly written in OES

- The Tale of Igor's Campaign – the most outstanding literary work in this language

- Russkaya Pravda – an eleventh-century legal code issued by Yaroslav the Wise

- Praying of Daniel the Immured

- A Journey Beyond the Three Seas

Attempts at compiling a lexicon of OES

The earliest attempts to compile a comprehensive lexicon of Old East Slavic were undertaken by Alexander Vostokov and Izmail Sreznevsky in the nineteenth century. Sreznevsky's Materials for the Dictionary of the Old Russian Language on the Basis of Written Records (1893–1903), though incomplete, remained a standard reference until the appearance of a 24-volume academic dictionary in 1975–99.

See also

- Belarusian language

- East Slavic languages

- Russian language

- Rusyn language

- Ruthenian language

- Slavic languages

- Ukrainian language

References

- "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: orv". SIL International (formerly known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics). Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Bunčić, Daniel (2015). On the dialectal basis of the Ruthenian literary language // Die Welt der Slaven, 60 (2). pp. 276–289. Otto Sagner. ISSN 0043-2520

- Helmut W. Schaller [de] Altostslawisch — Altukrainisch — Altrussisch. Zur Problematik der drei Bezeichnungen // Zeitschrift für Slawistik, Volume 35 Issue 1–6 (1990), Pages 754–761, ISSN 0044-3506 Template:Ref-de

- ^ "Old Russian". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Lunt, Horace G. Old Church Slavonic Grammar, Seventh Edition, 2001.

- "Мова (В.В.Німчук). 1. Історія української культури". Litopys.org.ua. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- "Юрій Шевельов. Історична фонологія української мови". Litopys.org.ua. 1979. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Ukrainian language // Encyclopædia Britannica 15th ed. (second version, Micropædia) Vol. 12: (1985–2010). 948 p.: p. 111 Template:Ref-en

- "Grand Principality of Moscow | medieval principality, Russia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- The Pushkin House, "Povest' Vremennykh Let" Archived 2015-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- BBM online library, "Povest' Vremennykh Let"

- The Library of Ukrainian literature, "Povist' minulikh lit"

- Russian online publications, "Povist' minulikh lit"

- Staražytnaja litaratura uschodnich slavian XI – XIII stahoddziaŭ

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (1953). The Russian Primary chronicle: Laurentian text. Mediaeval Academy of America. p. 51.

- "СЛОВО О ПЛЪКУ ИГОРЕВЂ. Слово о полку Ігоревім. Слово о полку Игореве". izbornyk.org.ua. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Slavonic, Old" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 227–228.

- Minns, Ellis Hovell (1911). "Slavs" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 228–237.

External links

- Book of Veles, English translation of the only book written in Old East Slavic which is supposed to have been written in 10th century AD

| Slavic languages | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||

| East Slavic | |||||||

| South Slavic |

| ||||||

| West Slavic |

| ||||||

| Microlanguages and dialects |

| ||||||

| Mixed languages | |||||||

| Constructed languages | |||||||

| Historical phonology | |||||||

| Italics indicate extinct languages. | |||||||