This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Angel Angel 2 (talk | contribs) at 18:30, 5 December 2019 (→See also). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:30, 5 December 2019 by Angel Angel 2 (talk | contribs) (→See also)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Dialects of Macedonian and Bulgarian| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Eastern South Slavic |

||||||

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

Alphabets

|

||||||

in Bulgarian: št

in Macedonian: kj(ḱ)

in Old Church Slavonic: št

in Serbo-Croatian and Russian: čj(ć)

in Slovenian and East Slavic: č

in West Slavic: c

According to Blaže Koneski, Bulgarian influenced the spread of the št reflex, while Serbian contributed to the development of palatalized(j) reflexes.

in Bulgarian: žd

in Belarusian and Ukrainian: ž

in Czech: z

in Macedonian: gj(ǵ)

in Old Church Slavonic: žd

in Polish and Slovak: dz

in Russian: žd, ž

in Serbo-Croatian: dj(đ)

in Slovenian: j

According to Blaže Koneski, Bulgarian influenced the spread of the žd reflex, while Serbian contributed to the development of palatalized(j) reflexes.

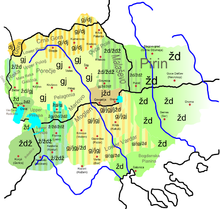

The Slavic dialects of Greece are the dialects of Macedonian and Bulgarian spoken by minority groups in the regions of Macedonia and Thrace in northern Greece. Usually, these dialects are classified as Bulgarian in Thrace, while the dialects in Macedonia are classified as either Macedonian or Bulgarian. Until the official codification of the Macedonian language in 1945 many linguists considered all these to be Bulgarian dialects.

Slavic dialects spoken in the region of Macedonia

The continuum of Macedonian and Bulgarian is spoken today in the prefectures of Florina and Pella, and to a lesser extent in Kastoria, Imathia, Kilkis, Thessaloniki, Serres and Drama.

According to Riki van Boeschoten, the Slavic dialects of Greek Macedonia are divided into three main dialects (Eastern, Central and Western), of which the Eastern dialect is used in the areas of Serres and Drama, and is closest to Bulgarian, the Western dialect is used in Florina and Kastoria, and is closest to Macedonian, the Central dialect is used in the area between Edessa and Salonica and is an intermediate between Macedonian and Bulgarian. Trudgill classifies certain peripheral dialects in the far east of Greek Macedonia as part of the Bulgarian language area and the rest as Macedonian dialects. Victor Friedman considers those Macedonian dialects, particularly those spoken as west as Kilkis, to be transitional to the neighbouring South Slavic language.

Macedonian dialectologists Božidar Vidoeski and Blaže Koneski consider the eastern Macedonian dialects to be transitional to Bulgarian, including the Maleševo-Pirin dialect.

Bulgarian dialectologists claim all dialects and do not recognize the Macedonian. They divide Bulgarian dialects mainly into Eastern and Western by a separating isogloss(dyado, byal/dedo, bel "grandpa, white"(m., sg.)) stretching from Salonica to the meeting point of Iskar and Danube, except for the isolated phenomena of the Korcha dialect as an of Eastern Bulgarian Rup dialects in the western fringes.

The nasal vowels are absent in all Slavic dialects except for the dialects of Macedonian in Greece and the Lechitic dialects (Polabian, Slovincian, Polish and Kashubian). This, along with the preservation of the paroxitonic in the Kostur dialect and Polish, is part of a series of isoglosses shared with the Lechitic dialects, which led to the thesis of a genetic relationship between Proto-Bulgarian and Proto-Macedonian with Proto-Polish and Proto-Kashubian.

The Old Church Slavonic language, the earliest recorded Slavic language, was based on the Salonica dialects. Church Slavonic, long-used as a state language further north in East and West Slavic states and as the only one in Wallachia and Moldavia until the 18th century, influenced other Slavic languages on all levels, including morphonology and vocabulary. 70% of Church Slavonic words are common to all Slavic languages, the influence of Church Slavonic is especially pronounced in Russian, which today consists of mixed native and Church Slavonic vocabulary.

Fringe views

A series of ethnological and pseudo-linguistic works were published by three Greek teachers, notably Boukouvalas and Tsioulkas, whose publications demonstrate common ideological and methodological similarities. They published etymological lists tracing every single Slavic word to Ancient Greek with fictional correlations, and they were ignorant of the dialects and the Slavic languages entirely. Among them, Boukouvalas promoted an enormous influence of the Greek language on a Bulgarian idiom and a discussion about their probable Greek descent. Tsioulkas followed him by publishing a large book, where he "proved" through an "etymological" approach, that these idioms are a pure Ancient Greek dialect. A publication of the third teacher followed, Giorgos Georgiades, who presented the language as a mixture of Greek, Turkish and other loanwords, but was incapable of deifining the dialects as either Greek or Slav.

Serbian dialectology does not usually extend the Serbian dialects to Greek Macedonia, but an unconventional classification has been maken by Aleksandar Belić, a convinced Serbian nationalist, who regarded the dialects as Serbian. In his classification he distinguished three categories of dialects in Greek Macedonia: a Serbo-Macedonian dialect, a Bulgaro-Macedonian teritorry where Serbian is spoken and a Non-Slavic territory.

Slavic dialects spoken in the region of Thrace

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2019) |

Extinct Slavic dialects

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2019) |

Features

|

See also

References

- See Ethnologue (); Euromosaic, Le (slavo)macédonien / bulgare en Grèce, L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce, Le valaque/aromoune-aroumane en Grèce, and Mercator-Education: European Network for Regional or Minority Languages and Education, The Turkish language in education in Greece. cf. also P. Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity", in S Barbour, C Carmichael (eds.), Language and nationalism in Europe, Oxford University Press 2000.

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica (15th ed.). Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 680. ISBN 9780852297872.(p. 680)(p. 680 continued)

- ^ Juliane Besters-Dilger, Cynthia Dermarkar, Stefan Pfänder, Achim Rabus. Congruence in Contact-Induced Language Change. De Gruyter. p. 57. ISBN 9783110373011.

Koneski (2001:178) conjectures that in the First Bulgarian Empire (9th–10th centuries), which governed the territory of present Macedonia, Bulgarian influenced the spread of phonological changes, such as those listed in (2a), while in the 13th and 14th centuries, the penetration of mediaeval Serbia into Macedonian regions contributed to the spread of changes such as those listed in (2b) and (2c):

(2) a. *tj > št and dj > žd

b. *tj > ѓ, *dj > g'

c. čr > cr{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Introduction to Russian phonology and word structure. Slavica Publishers. p. 128. ISBN 9780893570637.

- Mladenov, Stefan. Geschichte der bulgarischen Sprache, Berlin, Leipzig, 1929, § 207-209.

- Mazon, Andre. Contes Slaves de la Macédoine Sud-Occidentale: Etude linguistique; textes et traduction; Notes de Folklore, Paris 1923, p. 4.

- Селищев, Афанасий. Избранные труды, Москва 1968, с. 580-582.

- Die Slaven in Griechenland von Max Vasmer. Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1941. Kap. VI: Allgemeines und sprachliche Stellung der Slaven Griechenlands, p.324.

- "The European Union and Lesser-Used Languages". European Parliament. 2002: 77.

Macedonian and Bulgarian are the two standard languages of the eastern group of south Slavonic languages. In Greek Macedonia several dialectal varieties, very close to both standard Macedonian and Bulgarian, are spoken ... The two words (Macedonian and Bulgarian) are used here primarily because they are the names the speakers use to refer to the way they speak. In fact, many speak of 'our language' (nasi) or 'the local language' (ta dopia): the use of actual names is a politically charged national issue ... Yet (Slavo)Macedonian/ Bulgarian is still spoken by considerable numbers in Greek Macedonia, all along its northern borders, specially in the Prefectures of Florina, Pella, and to a lesser extent in Kastoria, Kilkis, Imathia, Thessalonika, Serres and Drama.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Boeschoten, Riki van (1993): Minority Languages in Northern Greece. Study Visit to Florina, Aridea, (Report to the European Commission, Brussels) "The Western dialect is used in Florina and Kastoria and is closest to the language used north of the border, the Eastern dialect is used in the areas of Serres and Drama and is closest to Bulgarian, the Central dialect is used in the area between Edessa and Salonica and forms an intermediate dialect"

- Ioannidou, Alexandra (1999). Questions on the Slavic Dialects of Greek Macedonia. Athens: Peterlang. p. 59, 63. ISBN 9783631350652.

In September 1993 ... the European Commission financed and published an interesting report by Riki van Boeschoten on the "Minority Languages in Northern Greece", in which the existence of a "Macedonian language" in Greece is mentioned. The description of this language is simplistic and by no means reflective of any kind of linguistic reality; instead it reflects the wish to divide up the dialects comprehensibly into geographical (i.e. political) areas. According to this report, Greek Slavophones speak the "Macedonian" language, which belongs to the "Bulgaro-Macedonian" group and is divided into three main dialects (Western, Central and Eastern) - a theory which lacks a factual basis.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.

- Heine, Bernd; Kuteva, Tania (2005). Language Contact and Grammatical Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780521608282.

in the modern northern and eastern Macedonian dialects that are transitional to Serbo-Croatian and Bulgarian, e.g. in Kumanovo and Kukus/Kilkis, object reduplication occurs with less consistency than in the west-central dialects

- Fodor,, István; Hagège, Claude (309). Language reform : history and future. Buske. ISBN 9783871189142.

The northern dialects are transitional to Serbo-Croatian, whereas the eastern (especially Malesevo) are transitional to Bulgarian. (For further details see Vidoeski 1960-1961, 1962-1963, and Koneski 1983).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Vidoeski, Božo. Dialects of Macedonian. Slavica. p. 33. ISBN 9780893573157.

the northern border zone and the extreme southeast towards Bulgarian linguistic territory. It was here that the formation of transitional dialect belts between Macedonian and Bulgarian in the east, and Macedonian and Serbian in the north began.

- "Карта на диалектната делитба на българския език". Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

- Bethin, Christina Y.; Bethin, Christina y (1998). Slavic Prosody: Language Change and Phonological Theory. 84-87: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521591485.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Hanna Popowska-Taborska. Wczesne Dzieje Slowianich jezyka. Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. Warszawa 2014, p. 99-100 “Chodzi o wnioskowanie na podstawie różnego rodzaju zbieżności językowych o domniemanym usytuowaniu przodków współczesnych reprezentantów języków słowiańskich w ich słowiańskiej praojczyźnie. Trzy najbardziej popularne w tym względzie koncepcje dotyczą: 1. domniemanych związków genetycznych Słowian północnych (nadbałtyckich) z północnym krańcem Słowiańszczyzny wschodniej, 2. domniemanych związków genetycznych Protopolaków (Protokaszubów) z Protobułgarami i Protomacedończykami oraz … Również żywa jest po dzień dzisiejszy wysunięta w 1940 r. przez Conewa teza o domniemanych genetycznych związkach polsko-bułgarskich, za którymi świadczyć mają charakteryzująca oba języki szeroka wymowa kontynuantów ě, nagłosowe o- poprzedzone protezą, zachowanie samogłosek nosowych w języku polskim i ślady tych samogłosek w języku bułgarskim, akcent paroksytoniczny cechujący język polski i dialekty kosturskie. Za dawnymi związkami lechicko-bułgarsko-macedońskimi opowiada się też Bernsztejn , który formułuje tezę, że przodkowie Bułgarów i Macedończyków żyli w przeszłości na północnym obszarze prasłowiańskim w bliskich związkach z przodkami Pomorzan i Polaków. Do wymienionych wyżej zbieżności fonetycznych dołącza Bernsztejn zbieżności leksykalne bułgarsko-kaszubskie; podobnie czynią Kurkina oraz Schuster-Šewc , którzy– opowiadając się za tezą Conewa i Bernsztejna – powołują się na mój artykuł o leksykalnych nawiązaniach kaszubsko-południowosłowiańskich ”

- Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 2010. p. 663. ISBN 9780080877754.

- Crișan, Marius-Mircea (2017). Dracula: An International Perspective. Springer. p. 114. ISBN 9783319633664.

- Die slavischen Sprachen / The Slavic Languages. Halbband 2. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. 2014. ISBN 9783110215472.

- Bennett, Brian P. (2011). Religion and Language in Post-Soviet Russia. Routledge. ISBN 9781136736131.

- ^ Ioannidou, Alexandra (1999). Questions on the Slavic Dialects of Greek Macedonia. Athens: Peterlang. p. 56-58. ISBN 9783631350652.

(A) series of etymological and pseudo-linguistic publications ... appeared in Greece ... by "specialists", such as the teachers Giorgos Boukouvalas and Konstantinos Tsioulkas. Boukouvalas published in 1905 in Cairo a brief brochure under the title "The language of the Bulgarophones in Macedonia" (1905). This essay, which assumed the Slav character of the foreign-language idioms of Greek Macedonia by naming them "Bulgarian", included a long list of Slavic words with Greek roots which are used in the dialects. ... Konstantinos Tsioulkas published in 1907 in Athens a book over 350 pages in length to prove the ancient Greek character of the idioms in Greek Macecionia!... : "Contributions to the bilinguism of the Macedonians by comparison of the Slav'-like Macedonian language to Greek" ... Tsioulkas "proved" through a series of "etymological" lists that the inhabitants of Greece's Macedonia spoke a pure Ancient-Greek dialect. ... In 1948 by a third teacher, Giorgos Georgiades, (wrote) under the promising title "The mixed idiom in Macedonia and the ethnological situation of the Macedonians who speak it". Here it is stated that many words from the dialects maintain their "Ancient Greek character". Still, the language itself was presented as a mixture of Greek, Turkish and words borrowed from other languages. As a result, the author found himself incapable of defining it as either Greek or Slav. In examining such publications, one will easily recognise ideological and methodological similarities. One common factor for all the authors is that they ignored not only the dialects they wrote about, but also the Slavic languages entirely. This fact did not hinder them in creating or republishing etymological lists tracing every Slavic word back to Ancient Greek with fictional correlations.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

Bibliography

- Trudgill P. (2000) "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity" in Language and Nationalism in Europe (Oxford : Oxford University Press)

- Iakovos D. Michailidis (1996) "Minority Rights and Educational Problems in Greek Interwar Macedonia: The Case of the Primer 'Abecedar'". Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 329-343

External links

| Slavic languages | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||

| East Slavic | |||||||

| South Slavic |

| ||||||

| West Slavic |

| ||||||

| Microlanguages and dialects |

| ||||||

| Mixed languages | |||||||

| Constructed languages | |||||||

| Historical phonology | |||||||

| Italics indicate extinct languages. | |||||||