This is an old revision of this page, as edited by InternetArchiveBot (talk | contribs) at 21:17, 29 May 2020 (Bluelink 2 books for verifiability (prndis)) #IABot (v2.0.1) (GreenC bot). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:17, 29 May 2020 by InternetArchiveBot (talk | contribs) (Bluelink 2 books for verifiability (prndis)) #IABot (v2.0.1) (GreenC bot)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine based on the doctrine of "like cures like"

| Alternative medicine | |

|---|---|

| Homoeopathy | |

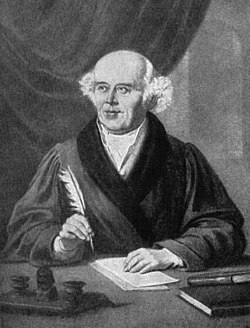

Samuel Hahnemann, originator of homeopathy Samuel Hahnemann, originator of homeopathy | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Claims | "Like cures like", dilution increases potency, disease caused by miasms. |

| Related fields | Alternative medicine |

| Year proposed | 1796 |

| Original proponents | Samuel Hahnemann |

| Subsequent proponents | James Tyler Kent, Constantine Hering, Royal S. Copeland, George Vithoulkas |

| MeSH | D006705 |

| See also | Humorism, heroic medicine |

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was created in 1796 by Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a disease in healthy people would cure similar symptoms in sick people; this doctrine is called similia similibus curentur, or "like cures like". Homeopathic preparations are termed remedies and are made using homeopathic dilution. In this process, a chosen substance is repeatedly and thoroughly diluted. The final product is chemically indistinguishable from the diluent, which is usually either distilled water, ethanol or sugar; often, not even a single molecule of the original substance can be expected to remain in the product. Between the dilution iterations homeopaths practice hitting and/or violently shaking the product, and claim that it makes the diluent remember the original substance after its removal. Practitioners claim that such preparations, upon oral intake, can treat or cure disease.

All relevant scientific knowledge about physics, chemistry, biochemistry and biology gained since at least the mid-19th century confirms that homeopathic remedies have no active content. They are biochemically inert, and have no effect on any known disease. Hahnemann's theory of disease, centered around principles he termed miasms, is inconsistent with subsequent identification of viruses and bacteria as causes of disease. Clinical trials have been conducted, and generally demonstrated no objective effect from homeopathic preparations. The fundamental implausibility of homeopathy as well as a lack of demonstrable effectiveness has led to it being characterized within the scientific and medical communities as quackery and nonsense.

After assessments of homeopathy, national and international bodies have recommended the withdrawal of government funding. Australia, the United Kingdom, Switzerland and France, as well as the European Academies' Science Advisory Council, and the Commission on Pseudoscience and Research Fraud of Russian Academy of Sciences each concluded that homeopathy is ineffective, and recommended against the practice receiving any further funding. Notably, France and England, where homeopathy was formerly prevalent, are in the process of removing all public funding. The National Health Service in England ceased funding homeopathic remedies in November 2017 and asked the Department of Health in the UK to add homeopathic remedies to the blacklist of forbidden prescription items, and France will remove funding by 2021. In November 2018, Spain also announced moves to ban homeopathy and other pseudotherapies.

History

Historical context

Hahnemann rejected the mainstream medicine of the late 18th century as irrational and inadvisable because it was largely ineffective and often harmful. He advocated the use of single drugs at lower doses and promoted an immaterial, vitalistic view of how living organisms function. The outcome from no treatment and adequate rest was usually superior to mainstream medicine as practiced at the time of homeopathy's inception.

Hahnemann's concept

See also: Samuel Hahnemann

The term "homeopathy" was coined by Hahnemann and first appeared in print in 1807.

Hahnemann conceived of homeopathy while translating a medical treatise by the Scottish physician and chemist William Cullen into German. Being sceptical of Cullen's theory concerning cinchona's use for curing malaria, Hahnemann ingested some bark specifically to investigate what would happen. He experienced fever, shivering and joint pain: symptoms similar to those of malaria itself. From this, Hahnemann came to believe that all effective drugs produce symptoms in healthy individuals similar to those of the diseases that they treat, in accord with the "law of similars" that had been proposed by ancient physicians. An account of the effects of eating cinchona bark noted by Oliver Wendell Holmes, and published in 1861, failed to reproduce the symptoms Hahnemann reported. Hahnemann's law of similars is an ipse dixit that does not derive from the scientific method. This led to the name "homeopathy", which comes from the Template:Lang-grc-gre hómoios, "-like" and πάθος páthos, "suffering".

Subsequent scientific work showed that cinchona cures malaria because it contains quinine, which kills the Plasmodium falciparum parasite that causes the disease; the mechanism of action is unrelated to Hahnemann's ideas.

"Provings"

Hahnemann began to test what effects substances may have produced in humans, a procedure later called "homeopathic proving". These tests required subjects to test the effects of ingesting substances by clearly recording all of their symptoms as well as the ancillary conditions under which they appeared. He published a collection of provings in 1805, and a second collection of 65 preparations appeared in his book, Materia Medica Pura (1810).

Because Hahnemann believed that large doses of drugs that caused similar symptoms would only aggravate illness, he advocated extreme dilutions of the substances; he devised a technique for making dilutions that he believed would preserve a substance's therapeutic properties while removing its harmful effects. Hahnemann believed that this process aroused and enhanced "the spirit-like medicinal powers of the crude substances". He gathered and published a complete overview of his new medical system in his book, The Organon of the Healing Art (1810), whose 6th edition, published in 1921, is still used by homeopaths today.

Miasms and disease

In the Organon, Hahnemann introduced the concept of "miasms" as "infectious principles" underlying chronic disease. Hahnemann associated each miasm with specific diseases, and thought that initial exposure to miasms causes local symptoms, such as skin or venereal diseases. If, however, these symptoms were suppressed by medication, the cause went deeper and began to manifest itself as diseases of the internal organs. Homeopathy maintains that treating diseases by directly alleviating their symptoms, as is sometimes done in conventional medicine, is ineffective because all "disease can generally be traced to some latent, deep-seated, underlying chronic, or inherited tendency". The underlying imputed miasm still remains, and deep-seated ailments can be corrected only by removing the deeper disturbance of the vital force.

Hahnemann's hypotheses for the direct or remote cause of all chronic diseases (miasms) originally presented only three: psora (the itch), syphilis (venereal disease) or sycosis (fig-wart disease). Of these three the most important was psora (Greek for "itch"), described as being related to any itching diseases of the skin, supposed to be derived from suppressed scabies, and claimed to be the foundation of many further disease conditions. Hahnemann believed psora to be the cause of such diseases as epilepsy, cancer, jaundice, deafness, and cataracts. Since Hahnemann's time, other miasms have been proposed, some replacing one or more of psora's proposed functions, including tuberculosis and cancer miasms.

The law of susceptibility implies that a negative state of mind can attract hypothetical disease entities called "miasms" to invade the body and produce symptoms of diseases. Hahnemann rejected the notion of a disease as a separate thing or invading entity, and insisted it was always part of the "living whole". Hahnemann coined the expression "allopathic medicine", which was used to pejoratively refer to traditional Western medicine.

Hahnemann's miasm theory remains disputed and controversial within homeopathy even in modern times. The theory of miasms has been criticized as an explanation developed by Hahnemann to preserve the system of homeopathy in the face of treatment failures, and for being inadequate to cover the many hundreds of sorts of diseases, as well as for failing to explain disease predispositions, as well as genetics, environmental factors, and the unique disease history of each patient.

19th century: rise to popularity and early criticism

Homeopathy achieved its greatest popularity in the 19th century. It was introduced to the United States in 1825 by Hans Birch Gram, a student of Hahnemann. The first homeopathic school in the US opened in 1835, and in 1844, the first US national medical association, the American Institute of Homeopathy, was established. Throughout the 19th century, dozens of homeopathic institutions appeared in Europe and the United States, and by 1900, there were 22 homeopathic colleges and 15,000 practitioners in the United States. Because medical practice of the time relied on ineffective and often dangerous treatments, patients of homeopaths often had better outcomes than those of the doctors of the time. Homeopathic preparations, even if ineffective, would almost surely cause no harm, making the users of homeopathic preparations less likely to be killed by the treatment that was supposed to be helping them. The relative success of homeopathy in the 19th century may have led to the abandonment of the ineffective and harmful treatments of bloodletting and purging and to have begun the move towards more effective, science-based medicine. One reason for the growing popularity of homeopathy was its apparent success in treating people suffering from infectious disease epidemics. During 19th-century epidemics of diseases such as cholera, death rates in homeopathic hospitals were often lower than in conventional hospitals, where the treatments used at the time were often harmful and did little or nothing to combat the diseases.

From its inception, however, homeopathy was criticized by mainstream science. Sir John Forbes, physician to Queen Victoria, said in 1843 that the extremely small doses of homeopathy were regularly derided as useless, "an outrage to human reason". James Young Simpson said in 1853 of the highly diluted drugs: "No poison, however strong or powerful, the billionth or decillionth of which would in the least degree affect a man or harm a fly." 19th-century American physician and author Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. was also a vocal critic of homeopathy and published an essay entitled Homœopathy and Its Kindred Delusions (1842). The members of the French Homeopathic Society observed in 1867 that some leading homeopathists of Europe not only were abandoning the practice of administering infinitesimal doses but were also no longer defending it. The last school in the US exclusively teaching homeopathy closed in 1920.

Revival in the 20th century

Main article: Regulation and prevalence of homeopathyAccording to Paul Ulrich Unschuld, the Nazi regime in Germany was fascinated by homeopathy, and spent large sums of money on researching its mechanisms, but without gaining a positive result. Unschuld further argues that homeopathy never subsequently took root in the United States, but remained more deeply established in European thinking. In the United States, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (sponsored by Royal Copeland, a Senator from New York and homeopathic physician) recognized homeopathic preparations as drugs. In the 1950s, there were only 75 pure homeopaths practising in the U.S. However, by the mid to late 1970s, homeopathy made a significant comeback and sales of some homeopathic companies increased tenfold. Some homeopaths give credit for the revival to Greek homeopath George Vithoulkas, who performed a "great deal of research to update the scenarios and refine the theories and practice of homeopathy", beginning in the 1970s, but Ernst and Singh consider it to be linked to the rise of the New Age movement. Whichever is correct, mainstream pharmacy chains recognized the business potential of selling homeopathic preparations. The Food and Drug Administration held a hearing April 20 and 21, 2015, requesting public comment on regulation of homeopathic drugs. The FDA cited the growth of sales of over-the-counter homeopathic medicines, which was $2.7 billion for 2007.

Bruce Hood has argued that the increased popularity of homeopathy in recent times may be due to the comparatively long consultations practitioners are willing to give their patients, and to an irrational preference for "natural" products, which people think are the basis of homeopathic preparations.

21st century

Since the beginning of the 21st century, a series of meta-analyses have further shown that the therapeutic claims of homeopathy lack scientific justification. In a 2010 report, the Science and Technology Committee of the United Kingdom House of Commons recommended that homeopathy should no longer be a beneficiary of NHS funding due its lack of scientific credibility; funding ceased in 2017. In March 2015, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia published an information paper on homeopathy. The main findings of the report were 'there are no health conditions for which there is reliable evidence that homeopathy is effective". Reactions to the report sparked world headlines which suggested that the NHMRC had found that homeopathy is not effective for all conditions.

In 2018, Australian pharmacies ignored recommendations for a homeopathic ban in the broader scope of the federal government accepting only three of the 45 recommendations made by the review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation (which were delivered in September 2017 to Health Minister Greg Hunt).

In 2019, the Canadian government stopped funding homeopathic foreign aid to Honduras. The Quebec charity Terre Sans Frontières had gotten $200,000 over five years from Global Affairs' Volunteer Cooperation Program. TSF supports homeopathic 'cures' for Chagas disease.

In July 2019, the French healthcare minister announced that social security reimbursements for homeopathic drugs will be phased out before 2021. France has long had a stronger belief in the virtues of homeopathic drugs than many other countries and the world's biggest manufacturer of alternative medicine drugs, Boiron, is located in that country.

Preparations and treatment

See also: List of homeopathic preparations

Homeopathic preparations are referred to as "homeopathics" or "remedies". Practitioners rely on two types of reference when prescribing: Materia medica and repertories. A homeopathic materia medica is a collection of "drug pictures", organized alphabetically. These entries describe the symptom patterns associated with individual preparations. A homeopathic repertory is an index of disease symptoms that lists preparations associated with specific symptoms. In both cases different compilers may dispute particular inclusions. The first symptomatic homeopathic materia medica was arranged by Hahnemann. The first homeopathic repertory was Georg Jahr's Symptomenkodex, published in German in 1835, and translated into English as the Repertory to the more Characteristic Symptoms of Materia Medica by Constantine Hering in 1838. This version was less focused on disease categories and was the forerunner to later works by James Tyler Kent. Repertories, in particular, may be very large.

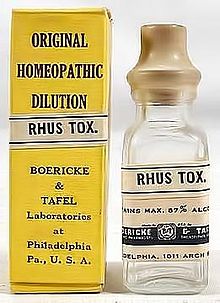

Homeopathy uses animal, plant, mineral, and synthetic substances in its preparations, generally referring to them using Latin or faux-Latin names. Examples include arsenicum album (arsenic oxide), natrum muriaticum (sodium chloride or table salt), Lachesis muta (the venom of the bushmaster snake), opium, and thyroidinum (thyroid hormone).

Some homeopaths use so-called nosodes (from the Greek nosos, disease) made from diseased or pathological products such as fecal, urinary, and respiratory discharges, blood, and tissue. Conversely, preparations made from "healthy" specimens are called "sarcodes".

Some modern homeopaths use preparations they call "imponderables" because they do not originate from a substance but some other phenomenon presumed to have been "captured" by alcohol or lactose. Examples include X-rays and sunlight.

Other minority practices include paper preparations, where the substance and dilution are written on pieces of paper and either pinned to the patients' clothing, put in their pockets, or placed under glasses of water that are then given to the patients, and the use of radionics to manufacture preparations. Such practices have been strongly criticized by classical homeopaths as unfounded, speculative, and verging upon magic and superstition.

Preparation

Hahnemann found that undiluted doses caused reactions, sometimes dangerous ones, so specified that preparations be given at the lowest possible dose. He found that this reduced potency as well as side-effects, but formed the view that vigorous shaking and striking on an elastic surface – a process he termed Schütteln, translated as succussion – nullified this. A common explanation for his settling on this process is said to be that he found preparations subjected to agitation in transit, such as in saddle bags or in a carriage, were more "potent". Hahnemann had a saddle-maker construct a special wooden striking board covered in leather on one side and stuffed with horsehair. Insoluble solids, such as granite, diamond, and platinum, are diluted by grinding them with lactose ("trituration").

The process of dilution and succussion is termed "dynamization" or "potentization" by homeopaths. In industrial manufacture this may be done by machine.

Serial dilution is achieved by taking an amount of the mixture and adding solvent, but the "Korsakovian" method may also be used, whereby the vessel in which the preparations are manufactured is emptied, refilled with solvent, and the volume of fluid adhering to the walls of the vessel is deemed sufficient for the new batch. The Korsakovian method is sometimes referred to as K on the label of a homeopathic preparation, e.g. 200CK is a 200C preparation made using the Korsakovian method.

Fluxion and radionics methods of preparation do not require succussion. There are differences of opinion on the number and force of strikes, and some practitioners dispute the need for succussion at all while others reject the Korsakovian and other non-classical preparations. There are no laboratory assays and the importance and techniques for succussion cannot be determined with any certainty from the literature.

Dilutions

Main article: Homeopathic dilutionsThree main logarithmic dilution scales are in regular use in homeopathy. Hahnemann created the "centesimal" or "C scale", diluting a substance by a factor of 100 at each stage. There is also a decimal dilution scale (notated as "X" or "D") in which the preparation is diluted by a factor of 10 at each stage. The centesimal scale was favoured by Hahnemann for most of his life.

A 2C dilution requires a substance to be diluted to one part in 100, and then some of that diluted solution diluted by a further factor of 100. This works out to one part of the original substance in 10,000 parts of the solution. A 6C dilution repeats this process six times, ending up with the original substance diluted by a factor of 100=10 (one part in one trillion or 1/1,000,000,000,000). Higher dilutions follow the same pattern. In homeopathy, a solution that is more dilute is described as having a higher "potency", and more dilute substances are considered by homeopaths to be stronger and deeper-acting.

The end product is usually so diluted as to be indistinguishable from the diluent (pure water, sugar or alcohol). Hahnemann advocated dilutions of 1 part to 10, that is 30C, for most purposes. Hahnemann regularly used dilutions up to 300C but opined that "there must be a limit to the matter, it cannot go on indefinitely". The greatest dilution reasonably likely to contain at least one molecule of the original substance is around 12C.

In Hahnemann's time, it was reasonable to assume the preparations could be diluted indefinitely, as the concept of the atom or molecule as the smallest possible unit of a chemical substance was just beginning to be recognized.

Critics and advocates of homeopathy alike commonly attempt to illustrate the dilutions involved in homeopathy with analogies. Hahnemann is reported to have joked that a suitable procedure to deal with an epidemic would be to empty a bottle of poison into Lake Geneva, if it could be succussed 60 times. Another example given by a critic of homeopathy states that a 12C solution is equivalent to a "pinch of salt in both the North and South Atlantic Oceans", which is approximately correct. One-third of a drop of some original substance diluted into all the water on earth would produce a preparation with a concentration of about 13C. A popular homeopathic treatment for the flu is a 200C dilution of duck liver, marketed under the name Oscillococcinum. As there are only about 10 atoms in the entire observable universe, a dilution of one molecule in the observable universe would be about 40C. Oscillococcinum would thus require 10 more universes to simply have one molecule in the final substance. The high dilutions characteristically used are often considered to be the most controversial and implausible aspect of homeopathy.

Not all homeopaths advocate high dilutions. Preparations at concentrations below 4X are considered an important part of homeopathic heritage. Many of the early homeopaths were originally doctors and generally used lower dilutions such as "3X" or "6X", rarely going beyond "12X". The split between lower and higher dilutions followed ideological lines. Those favouring low dilutions stressed pathology and a stronger link to conventional medicine, while those favouring high dilutions emphasized vital force, miasms and a spiritual interpretation of disease. Some products with such relatively lower dilutions continue to be sold, but like their counterparts, they have not been conclusively demonstrated to have any effect beyond that of a placebo.

Provings

Homeopaths say that they can determine the properties of their preparations by following a method which they call "proving". As performed by Hahnemann, provings involved administering various preparations to healthy volunteers. The volunteers were then observed, often for months at a time. They were made to keep extensive journals detailing all of their symptoms at specific times throughout the day. They were forbidden from consuming coffee, tea, spices, or wine for the duration of the experiment; playing chess was also prohibited because Hahnemann considered it to be "too exciting", though they were allowed to drink beer and encouraged to exercise in moderation.

At first Hahnemann used undiluted doses for provings, but he later advocated provings with preparations at a 30C dilution (1 part in ), and most modern provings are carried out using ultra-dilute preparations.

Provings are claimed to have been important in the development of the clinical trial, due to their early use of simple control groups, systematic and quantitative procedures, and some of the first application of statistics in medicine. The lengthy records of self-experimentation by homeopaths have occasionally proven useful in the development of modern drugs: For example, evidence that nitroglycerin might be useful as a treatment for angina was discovered by looking through homeopathic provings, though homeopaths themselves never used it for that purpose at that time. The first recorded provings were published by Hahnemann in his 1796 Essay on a New Principle. His Fragmenta de Viribus (1805) contained the results of 27 provings, and his 1810 Materia Medica Pura contained 65. For James Tyler Kent's 1905 Lectures on Homoeopathic Materia Medica, 217 preparations underwent provings and newer substances are continually added to contemporary versions.

Though the proving process has superficial similarities with clinical trials, it is fundamentally different in that the process is subjective, not blinded, and modern provings are unlikely to use pharmacologically active levels of the substance under proving. As early as 1842, Holmes noted the provings were impossibly vague, and the purported effect was not repeatable among different subjects.

See also: NoceboConsultation

Homeopaths generally begin with detailed examinations of their patients' histories, including questions regarding their physical, mental and emotional states, their life circumstances and any physical or emotional illnesses. ].</ref> outdated source, statement can be reintroduced when a better source is found -->The homeopath then attempts to translate this information into a complex formula of mental and physical symptoms, including likes, dislikes, innate predispositions and even body type.

From these symptoms, the homeopath chooses how to treat the patient using materia medica and repertories. In classical homeopathy, the practitioner attempts to match a single preparation to the totality of symptoms (the simlilum), while "clinical homeopathy" involves combinations of preparations based on the various symptoms of an illness.

Pills and active ingredients

Homeopathic pills are made from an inert substance (often sugars, typically lactose), upon which a drop of liquid homeopathic preparation is placed and allowed to evaporate.

The process of homeopathic dilution results in no objectively detectable active ingredient in most cases, but some preparations (e.g. calendula and arnica creams) do contain pharmacologically active doses. One product, Zicam Cold Remedy, which was marketed as an "unapproved homeopathic" product, contains two ingredients that are only "slightly" diluted: zinc acetate (2X = 1/100 dilution) and zinc gluconate (1X = 1/10 dilution), which means both are present in a biologically active concentration strong enough to have caused some people to lose their sense of smell, a condition termed anosmia. Zicam also listed several normal homeopathic potencies as "inactive ingredients", including galphimia glauca, histamine dihydrochloride (homeopathic name, histaminum hydrochloricum), luffa operculata, and sulfur.

Related and minority treatments and practices

Isopathy

Isopathy is a therapy derived from homeopathy, invented by Johann Joseph Wilhelm Lux in the 1830s. Isopathy differs from homeopathy in general in that the preparations, known as "nosodes", are made up either from things that cause the disease or from products of the disease, such as pus. Many so-called "homeopathic vaccines" are a form of isopathy. Tautopathy is a form of isopathy where the preparations are composed of drugs or vaccines that a person has consumed in the past, in the belief that this can reverse lingering damage caused by the initial use. There is no convincing scientific evidence for isopathy as an effective method of treatment.

Flower preparations

Flower preparations can be produced by placing flowers in water and exposing them to sunlight. The most famous of these are the Bach flower remedies, which were developed by the physician and homeopath Edward Bach. Although the proponents of these preparations share homeopathy's vitalist world-view and the preparations are claimed to act through the same hypothetical "vital force" as homeopathy, the method of preparation is different. Bach flower preparations are manufactured in allegedly "gentler" ways such as placing flowers in bowls of sunlit water, and the preparations are not succussed. There is no convincing scientific or clinical evidence for flower preparations being effective.

Veterinary use

The idea of using homeopathy as a treatment for other animals termed "veterinary homeopathy", dates back to the inception of homeopathy; Hahnemann himself wrote and spoke of the use of homeopathy in animals other than humans. The FDA has not approved homeopathic products as veterinary medicine in the U.S. In the UK, veterinary surgeons who use homeopathy may belong to the Faculty of Homeopathy and/or to the British Association of Homeopathic Veterinary Surgeons. Animals may be treated only by qualified veterinary surgeons in the UK and some other countries. Internationally, the body that supports and represents homeopathic veterinarians is the International Association for Veterinary Homeopathy.

The use of homeopathy in veterinary medicine is controversial; the little existing research on the subject is not of a high enough scientific standard to provide reliable data on efficacy. Given that homeopathy's effects in humans appear to be mainly due to the placebo effect and the counseling aspects of the consultation, it is unlikely that homeopathic treatments would be effective in animals. Other studies have also found that giving animals placebos can play active roles in influencing pet owners to believe in the effectiveness of the treatment when none exists. The British Veterinary Association's position statement on alternative medicines says that it "cannot endorse" homeopathy, and the Australian Veterinary Association includes it on its list of "ineffective therapies". A 2016 review of peer-reviewed articles from 1981 to 2014 by scientists from the University of Kassel, Germany, concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of homeopathy in livestock as a way to prevent or treat infectious diseases.

The UK's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has adopted a robust position against use of "alternative" pet preparations including homeopathy.

Electrohomeopathy

Main article: ElectrohomeopathyElectrohomoeopathy is a derivative of homeopathy. The name refers to an electric bio-energy supposedly extracted from plants and of therapeutic value, rather than electricity in its conventional sense, combined with homeopathy. Popular in the late nineteenth century, electrohomeopathy is considered pseudo scientific and has been described as "utter idiocy".

In 2012, the Allahabad High Court in Uttar Pradesh, India, handed down a decree which stated that electrohomeopathy was an unrecognized system of medicine which was quackery.

Homeoprophylaxis

Main article: HomeoprophylaxisThe use of homeopathy as a preventive for serious infectious diseases is especially controversial, in the context of ill-founded public alarm over the safety of vaccines stoked by the anti-vaccination movement. Promotion of homeopathic alternatives to vaccines has been characterized as dangerous, inappropriate and irresponsible. In December 2014, the Australian homeopathy supplier Homeopathy Plus! was found to have acted deceptively in promoting homeopathic alternatives to vaccines. In 2019, an investigative journalism piece by the Telegraph revealed that homeopathy practitioners were actively discouraging patients from vaccinating their children.

Evidence and efficacy

The very low concentration of homeopathic preparations, which often lack even a single molecule of the diluted substance, has been the basis of questions about the effects of the preparations since the 19th century. Modern advocates of homeopathy have proposed a concept of "water memory", according to which water "remembers" the substances mixed in it, and transmits the effect of those substances when consumed. This concept is inconsistent with the current understanding of matter, and water memory has never been demonstrated to have any detectable effect, biological or otherwise.

James Randi and the 10:23 campaign groups have highlighted the lack of active ingredients in most homeopathic products by taking large 'overdoses'. None of the hundreds of demonstrators in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US were injured and "no one was cured of anything, either".

Outside of the alternative medicine community, scientists have long considered homeopathy a sham or a pseudoscience, and the mainstream medical community regards it as quackery. There is an overall absence of sound statistical evidence of therapeutic efficacy, which is consistent with the lack of any biologically plausible pharmacological agent or mechanism.

Abstract concepts within theoretical physics have been invoked to suggest explanations of how or why preparations might work, including quantum entanglement, quantum nonlocality, the theory of relativity and chaos theory. Contrariwise, quantum superposition has been invoked to explain why homeopathy does not work in double-blind trials. However, the explanations are offered by nonspecialists within the field, and often include speculations that are incorrect in their application of the concepts and not supported by actual experiments. Several of the key concepts of homeopathy conflict with fundamental concepts of physics and chemistry. The use of quantum entanglement to explain homeopathy's purported effects is "patent nonsense", as entanglement is a delicate state that rarely lasts longer than a fraction of a second. While entanglement may result in certain aspects of individual subatomic particles acquiring linked quantum states, this does not mean the particles will mirror or duplicate each other, nor cause health-improving transformations.

Plausibility

The proposed mechanisms for homeopathy are precluded from having any effect by the laws of physics and physical chemistry. The extreme dilutions used in homeopathic preparations usually leave not one molecule of the original substance in the final product.

A number of speculative mechanisms have been advanced to counter this, the most widely discussed being water memory, though this is now considered erroneous since short-range order in water only persists for about 1 picosecond. No evidence of stable clusters of water molecules was found when homeopathic preparations were studied using nuclear magnetic resonance, and many other physical experiments in homeopathy have been found to be of low methodological quality, which precludes any meaningful conclusion. Existence of a pharmacological effect in the absence of any true active ingredient is inconsistent with the law of mass action and the observed dose-response relationships characteristic of therapeutic drugs (whereas placebo effects are non-specific and unrelated to pharmacological activity).

Homeopaths contend that their methods produce a therapeutically active preparation, selectively including only the intended substance, though critics note that any water will have been in contact with millions of different substances throughout its history, and homeopaths have not been able to account for a reason why only the selected homeopathic substance would be a special case in their process. For comparison, ISO 3696:1987 defines a standard for water used in laboratory analysis; this allows for a contaminant level of ten parts per billion, 4C in homeopathic notation. This water may not be kept in glass as contaminants will leach out into the water.

Practitioners of homeopathy hold that higher dilutions―described as being of higher potency―produce stronger medicinal effects. This idea is also inconsistent with observed dose-response relationships, where effects are dependent on the concentration of the active ingredient in the body. This dose-response relationship has been confirmed in myriad experiments on organisms as diverse as nematodes, rats, and humans. Some homeopaths contend that the phenomenon of hormesis may support the idea of dilution increasing potency, but the dose-response relationship outside the zone of hormesis declines with dilution as normal, and nonlinear pharmacological effects do not provide any credible support for homeopathy.

Physicist Robert L. Park, former executive director of the American Physical Society, is quoted as saying:"since the least amount of a substance in a solution is one molecule, a 30C solution would have to have at least one molecule of the original substance dissolved in a minimum of 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,

The laws of chemistry state that there is a limit to the dilution that can be made without losing the original substance altogether. This limit, which is related to Avogadro's number, is roughly equal to homeopathic dilutions of 12C or 24X (1 part in 10).

Scientific tests run by both the BBC's Horizon and ABC's 20/20 programmes were unable to differentiate homeopathic dilutions from water, even when using tests suggested by homeopaths themselves.

In May 2018, the German skeptical organization GWUP issued an invitation to individuals and groups to respond to its challenge "to identify homeopathic preparations in high potency and to give a detailed description on how this can be achieved reproducibly." The first participant to correctly identify selected homeopathic preparations under an agreed-upon protocol will receive €50,000.

Efficacy

No individual homeopathic preparation has been unambiguously shown by research to be different from placebo. The methodological quality of the primary research was generally low, with such problems as weaknesses in study design and reporting, small sample size, and selection bias. Since better quality trials have become available, the evidence for efficacy of homeopathy preparations has diminished; the highest-quality trials indicate that the preparations themselves exert no intrinsic effect. A review conducted in 2010 of all the pertinent studies of "best evidence" produced by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that "the most reliable evidence – that produced by Cochrane reviews – fails to demonstrate that homeopathic medicines have effects beyond placebo."

Government level reviews

Government-level reviews have been conducted in recent years by Switzerland (2005), the United Kingdom (2009), Australia (2015) and the European Academies' Science Advisory Council (2017).

The Swiss programme for the evaluation of complementary medicine (PEK) resulted in the peer-reviewed Shang publication (see Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of efficacy) and a controversial competing analysis by homeopaths and advocates led by Gudrun Bornhöft and Peter Matthiessen, which has misleadingly been presented as a Swiss government report by homeopathy proponents, a claim that has been repudiated by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The Swiss Government terminated reimbursement, though it was subsequently reinstated after a political campaign and referendum for a further six-year trial period.

The United Kingdom's House of Commons Science and Technology Committee sought written evidence and submissions from concerned parties and, following a review of all submissions, concluded that there was no compelling evidence of effect other than placebo and recommended that the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) should not allow homeopathic product labels to make medical claims, that homeopathic products should no longer be licensed by the MHRA, as they are not medicines, and that further clinical trials of homeopathy could not be justified. They recommended that funding of homeopathic hospitals should not continue, and NHS doctors should not refer patients to homeopaths. By February 2011 only one-third of primary care trusts still funded homeopathy and by 2012 no British universities offered homeopathy courses. In July 2017, as part of a plan to save £200m a year by preventing the "misuse of scarce" funding, the NHS announced that it would no longer provide homeopathic medicines. A legal appeal by the British Homeopathic Association against the decision was rejected in June 2018.

The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council completed a comprehensive review of the effectiveness of homeopathic preparations in 2015, in which it concluded that "there were no health conditions for which there was reliable evidence that homeopathy was effective. No good-quality, well-designed studies with enough participants for a meaningful result reported either that homeopathy caused greater health improvements than placebo, or caused health improvements equal to those of another treatment."

On September 20, 2017, the European Academies' Science Advisory Council (EASAC) published its official analysis and conclusion on the use of homeopathic products, finding a lack of evidence that homeopathic products are effective, and raising concerns about quality control.

Publication bias and other methodological problems

Further information: Statistical hypothesis testing, P-value, and Publication biasThe fact that individual randomized controlled trials have given positive results is not in contradiction with an overall lack of statistical evidence of efficacy. A small proportion of randomized controlled trials inevitably provide false-positive outcomes due to the play of chance: a statistically significant positive outcome is commonly adjudicated when the probability of it being due to chance rather than a real effect is no more than 5%―a level at which about 1 in 20 tests can be expected to show a positive result in the absence of any therapeutic effect. Furthermore, trials of low methodological quality (i.e. ones that have been inappropriately designed, conducted or reported) are prone to give misleading results. In a systematic review of the methodological quality of randomized trials in three branches of alternative medicine, Linde et al. highlighted major weaknesses in the homeopathy sector, including poor randomization. A separate 2001 systematic review that assessed the quality of clinical trials of homeopathy found that such trials were generally of lower quality than trials of conventional medicine.

A related issue is publication bias: researchers are more likely to submit trials that report a positive finding for publication, and journals prefer to publish positive results. Publication bias has been particularly marked in alternative medicine journals, where few of the published articles (just 5% during the year 2000) tend to report null results. Regarding the way in which homeopathy is represented in the medical literature, a systematic review found signs of bias in the publications of clinical trials (towards negative representation in mainstream medical journals, and vice versa in alternative medicine journals), but not in reviews.

Positive results are much more likely to be false if the prior probability of the claim under test is low.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of efficacy

Both meta-analyses, which statistically combine the results of several randomized controlled trials, and other systematic reviews of the literature are essential tools to summarize evidence of therapeutic efficacy. Early systematic reviews and meta-analyses of trials evaluating the efficacy of homeopathic preparations in comparison with placebo more often tended to generate positive results, but appeared unconvincing overall. In particular, reports of three large meta-analyses warned readers that firm conclusions could not be reached, largely due to methodological flaws in the primary studies and the difficulty in controlling for publication bias. The positive finding of one of the most prominent of the early meta-analyses, published in The Lancet in 1997 by Linde et al., was later reframed by the same research team, who wrote:

The evidence of bias weakens the findings of our original meta-analysis. Since we completed our literature search in 1995, a considerable number of new homeopathy trials have been published. The fact that a number of the new high-quality trials ... have negative results, and a recent update of our review for the most "original" subtype of homeopathy (classical or individualized homeopathy), seem to confirm the finding that more rigorous trials have less-promising results. It seems, therefore, likely that our meta-analysis at least overestimated the effects of homeopathic treatments.

Subsequent work by John Ioannidis and others has shown that for treatments with no prior plausibility, the chances of a positive result being a false positive are much higher, and that any result not consistent with the null hypothesis should be assumed to be a false positive.

A systematic review of the available systematic reviews confirmed in 2002 that higher-quality trials tended to have less positive results, and found no convincing evidence that any homeopathic preparation exerts clinical effects different from placebo.

In 2005, The Lancet medical journal published a meta-analysis of 110 placebo-controlled homeopathy trials and 110 matched medical trials based upon the Swiss government's Programme for Evaluating Complementary Medicine, or PEK. The study concluded that its findings were "compatible with the notion that the clinical effects of homeopathy are placebo effects". This was accompanied by an editorial pronouncing "The end of homoeopathy". A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis found that the most reliable evidence did not support the effectiveness of non-individualized homeopathy. The authors noted that "the quality of the body of evidence is low."

Other meta-analyses include homeopathic treatments to reduce cancer therapy side-effects following radiotherapy and chemotherapy, allergic rhinitis, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and childhood diarrhoea, adenoid vegetation, asthma, upper respiratory tract infection in children, insomnia, fibromyalgia, psychiatric conditions and Cochrane Library systematic reviews of homeopathic treatments for asthma, dementia, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, induction of labour, upper respiratory tract infections in children, and irritable bowel syndrome. Other reviews covered osteoarthritis, migraines, postoperative ecchymosis and edema, delayed-onset muscle soreness, preventing postpartum haemorrhage, or eczema and other dermatological conditions.

Some clinical trials have tested individualized homeopathy, and there have been reviews of this, specifically. A 1998 review found 32 trials that met their inclusion criteria, 19 of which were placebo-controlled and provided enough data for meta-analysis. These 19 studies showed a pooled odds ratio of 1.17 to 2.23 in favour of individualized homeopathy over the placebo, but no difference was seen when the analysis was restricted to the methodologically best trials. The authors concluded that "the results of the available randomized trials suggest that individualized homeopathy has an effect over placebo. The evidence, however, is not convincing because of methodological shortcomings and inconsistencies." Jay Shelton, author of a book on homeopathy, has stated that the claim assumes without evidence that classical, individualized homeopathy works better than nonclassical variations. A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis found that individualized homeopathic remedies may be slightly more effective than placebos, though the authors noted that their findings were based on low- or unclear-quality evidence. The same research team later reported that taking into account model validity did not significantly affect this conclusion.

The results of reviews are generally negative or only weakly positive, and reviewers consistently report the poor quality of trials. The finding of Linde et. al. that more rigorous studies produce less positive results is supported in several and contradicted by none.

Statements by major medical organizations

Health organizations such as the UK's National Health Service, the American Medical Association, the FASEB, and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, have issued statements of their conclusion that there is "no good-quality evidence that homeopathy is effective as a treatment for any health condition". In 2009, World Health Organization official Mario Raviglione criticized the use of homeopathy to treat tuberculosis; similarly, another WHO spokesperson argued there was no evidence homeopathy would be an effective treatment for diarrhoea. They warned against the use of homeopathy for serious conditions such as depression, HIV and malaria.

The American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology recommend that no one use homeopathic treatment for disease or as a preventive health measure. These organizations report that no evidence exists that homeopathic treatment is effective, but that there is evidence that using these treatments produces harm and can bring indirect health risks by delaying conventional treatment.

Explanations of perceived effects

Science offers a variety of explanations for how homeopathy may appear to cure diseases or alleviate symptoms even though the preparations themselves are inert:

- The placebo effect – the intensive consultation process and expectations for the homeopathic preparations may cause the effect.

- Therapeutic effect of the consultation – the care, concern, and reassurance a patient experiences when opening up to a compassionate caregiver can have a positive effect on the patient's well-being.

- Unassisted natural healing – time and the body's ability to heal without assistance can eliminate many diseases of their own accord.

- Unrecognized treatments – an unrelated food, exercise, environmental agent, or treatment for a different ailment, may have occurred.

- Regression towards the mean – since many diseases or conditions are cyclical, symptoms vary over time and patients tend to seek care when discomfort is greatest; they may feel better anyway but because of the timing of the visit to the homeopath they attribute improvement to the preparation taken.

- Non-homeopathic treatment – patients may also receive standard medical care at the same time as homeopathic treatment, and the former is responsible for improvement.

- Cessation of unpleasant treatment – often homeopaths recommend patients stop getting medical treatment such as surgery or drugs, which can cause unpleasant side-effects; improvements are attributed to homeopathy when the actual cause is the cessation of the treatment causing side-effects in the first place, but the underlying disease remains untreated and still dangerous to the patient.

Purported effects in other biological systems

While some articles have suggested that homeopathic solutions of high dilution can have statistically significant effects on organic processes including the growth of grain, histamine release by leukocytes, and enzyme reactions, such evidence is disputed since attempts to replicate them have failed. A 2007 systematic review of high-dilution experiments found that none of the experiments with positive results could be reproduced by all investigators.

In 1987, French immunologist Jacques Benveniste submitted a paper to the journal Nature while working at INSERM. The paper purported to have discovered that basophils, a type of white blood cell, released histamine when exposed to a homeopathic dilution of anti-immunoglobulin E antibody. The journal editors, sceptical of the results, requested that the study be replicated in a separate laboratory. Upon replication in four separate laboratories the study was published. Still sceptical of the findings, Nature assembled an independent investigative team to determine the accuracy of the research, consisting of Nature editor and physicist Sir John Maddox, American scientific fraud investigator and chemist Walter Stewart, and sceptic James Randi. After investigating the findings and methodology of the experiment, the team found that the experiments were "statistically ill-controlled", "interpretation has been clouded by the exclusion of measurements in conflict with the claim", and concluded, "We believe that experimental data have been uncritically assessed and their imperfections inadequately reported." James Randi stated that he doubted that there had been any conscious fraud, but that the researchers had allowed "wishful thinking" to influence their interpretation of the data.

In 2001 and 2004, Madeleine Ennis published a number of studies that reported that homeopathic dilutions of histamine exerted an effect on the activity of basophils. In response to the first of these studies, Horizon aired a programme in which British scientists attempted to replicate Ennis' results; they were unable to do so.

Ethics and safety

The provision of homeopathic preparations has been described as unethical. Michael Baum, Professor Emeritus of Surgery and visiting Professor of Medical Humanities at University College London (UCL), has described homoeopathy as a "cruel deception".

Edzard Ernst, the first Professor of Complementary Medicine in the United Kingdom and a former homeopathic practitioner, has expressed his concerns about pharmacists who violate their ethical code by failing to provide customers with "necessary and relevant information" about the true nature of the homeopathic products they advertise and sell:

- "My plea is simply for honesty. Let people buy what they want, but tell them the truth about what they are buying. These treatments are biologically implausible and the clinical tests have shown they don't do anything at all in human beings. The argument that this information is not relevant or important for customers is quite simply ridiculous."

Patients who choose to use homeopathy rather than evidence-based medicine risk missing timely diagnosis and effective treatment of serious conditions such as cancer.

In 2013 the UK Advertising Standards Authority concluded that the Society of Homeopaths were targeting vulnerable ill people and discouraging the use of essential medical treatment while making misleading claims of efficacy for homeopathic products.

In 2015 the Federal Court of Australia imposed penalties on a homeopathic company, Homeopathy Plus! Pty Ltd and its director, for making false or misleading statements about the efficacy of the whooping cough vaccine and homeopathic remedies as an alternative to the whooping cough vaccine, in breach of the Australian Consumer Law.

Adverse effects

Some homeopathic preparations involve poisons such as Belladonna, arsenic, and poison ivy, which are highly diluted in the homeopathic preparation. In rare cases, the original ingredients are present at detectable levels. This may be due to improper preparation or intentional low dilution. Serious adverse effects such as seizures and death have been reported or associated with some homeopathic preparations.

On September 30, 2016 the FDA issued a safety alert to consumers warning against the use of homeopathic teething gels and tablets following reports of adverse events after their use. The agency recommended that parents discard these products and "seek advice from their health care professional for safe alternatives" to homeopathy for teething. The pharmacy CVS announced, also on September 30, that it was voluntarily withdrawing the products from sale and on October 11 Hyland's (the manufacturer) announced that it was discontinuing their teething medicine in the United States though the products remain on sale in Canada. On October 12, Buzzfeed reported that the regulator had "examined more than 400 reports of seizures, fever and vomiting, as well as 10 deaths" over a six-year period. The investigation (including analyses of the products) is still ongoing and the FDA does not know yet if the deaths and illnesses were caused by the products. However a previous FDA investigation in 2010, following adverse effects reported then, found that these same products were improperly diluted and contained "unsafe levels of belladonna, also known as deadly nightshade" and that the reports of serious adverse events in children using this product were "consistent with belladonna toxicity".

Instances of arsenic poisoning have occurred after use of arsenic-containing homeopathic preparations. Zicam Cold remedy Nasal Gel, which contains 2X (1:100) zinc gluconate, reportedly caused a small percentage of users to lose their sense of smell; 340 cases were settled out of court in 2006 for 12 million U.S. dollars. In 2009, the FDA advised consumers to stop using three discontinued cold remedy Zicam products because it could cause permanent damage to users' sense of smell. Zicam was launched without a New Drug Application (NDA) under a provision in the FDA's Compliance Policy Guide called "Conditions under which homeopathic drugs may be marketed" (CPG 7132.15), but the FDA warned Matrixx Initiatives, its manufacturer, via a Warning Letter that this policy does not apply when there is a health risk to consumers.

A 2000 review by homeopaths reported that homeopathic preparations are "unlikely to provoke severe adverse reactions". In 2012, a systematic review evaluating evidence of homeopathy's possible adverse effects concluded that "homeopathy has the potential to harm patients and consumers in both direct and indirect ways". One of the reviewers, Edzard Ernst, supplemented the article on his blog, writing: "I have said it often and I say it again: if used as an alternative to an effective cure, even the most 'harmless' treatment can become life-threatening." A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in homeopathic clinical trials, adverse effects were reported among the patients who received homeopathy about as often as they were reported among patients who received placebo or conventional medicine.

Lack of efficacy

The lack of convincing scientific evidence supporting its efficacy and its use of preparations without active ingredients have led to characterizations as pseudoscience and quackery, or, in the words of a 1998 medical review, "placebo therapy at best and quackery at worst". The Russian Academy of Sciences considers homeopathy a "dangerous 'pseudoscience' that does not work", and "urges people to treat homeopathy 'on a par with magic'". The Chief Medical Officer for England, Dame Sally Davies, has stated that homeopathic preparations are "rubbish" and do not serve as anything more than placebos. Jack Killen, acting deputy director of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, says homeopathy "goes beyond current understanding of chemistry and physics". He adds: "There is, to my knowledge, no condition for which homeopathy has been proven to be an effective treatment." Ben Goldacre says that homeopaths who misrepresent scientific evidence to a scientifically illiterate public, have "... walled themselves off from academic medicine, and critique has been all too often met with avoidance rather than argument". Homeopaths often prefer to ignore meta-analyses in favour of cherry picked positive results, such as by promoting a particular observational study (one which Goldacre describes as "little more than a customer-satisfaction survey") as if it were more informative than a series of randomized controlled trials.

Referring specifically to homeopathy, the British House of Commons Science and Technology Committee has stated:

In our view, the systematic reviews and meta-analyses conclusively demonstrate that homeopathic products perform no better than placebos. The Government shares our interpretation of the evidence.

In the Committee's view, homeopathy is a placebo treatment and the Government should have a policy on prescribing placebos. The Government is reluctant to address the appropriateness and ethics of prescribing placebos to patients, which usually relies on some degree of patient deception. Prescribing of placebos is not consistent with an informed patient choice – which the Government claims is very important – as it means patients do not have all the information needed to make choice meaningful. Beyond ethical issues and the integrity of the doctor-patient relationship, prescribing pure placebos is bad medicine. Their effect is unreliable and unpredictable and cannot form the sole basis of any treatment on the NHS.

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the United States' National Institutes of Health states:

Homeopathy is a controversial topic in complementary medicine research. A number of the key concepts of homeopathy are not consistent with fundamental concepts of chemistry and physics. For example, it is not possible to explain in scientific terms how a preparation containing little or no active ingredient can have any effect. This, in turn, creates major challenges to the rigorous clinical investigation of homeopathic preparations. For example, one cannot confirm that an extremely dilute preparation contains what is listed on the label, or develop objective measures that show effects of extremely dilute preparations in the human body.

Ben Goldacre noted that in the early days of homeopathy, when medicine was dogmatic and frequently worse than doing nothing, homeopathy at least failed to make matters worse:

During the 19th-century cholera epidemic, death rates at the London Homeopathic Hospital were three times lower than at the Middlesex Hospital. Homeopathic sugar pills won't do anything against cholera, of course, but the reason for homeopathy's success in this epidemic is even more interesting than the placebo effect: at the time, nobody could treat cholera. So, while hideous medical treatments such as blood-letting were actively harmful, the homeopaths' treatments at least did nothing either way.

In lieu of standard medical treatment

On clinical grounds, patients who choose to use homeopathy in preference to normal medicine risk missing timely diagnosis and effective treatment, thereby worsening the outcomes of serious conditions. Critics of homeopathy have cited individual cases of patients of homeopathy failing to receive proper treatment for diseases that could have been easily diagnosed and managed with conventional medicine and who have died as a result, and the "marketing practice" of criticizing and downplaying the effectiveness of mainstream medicine. Homeopaths claim that use of conventional medicines will "push the disease deeper" and cause more serious conditions, a process referred to as "suppression". Some homeopaths (particularly those who are non-physicians) advise their patients against immunization. Some homeopaths suggest that vaccines be replaced with homeopathic "nosodes", created from biological materials such as pus, diseased tissue, bacilli from sputum or (in the case of "bowel nosodes") faeces. While Hahnemann was opposed to such preparations, modern homeopaths often use them although there is no evidence to indicate they have any beneficial effects. Cases of homeopaths advising against the use of anti-malarial drugs have been identified. This puts visitors to the tropics who take this advice in severe danger, since homeopathic preparations are completely ineffective against the malaria parasite. Also, in one case in 2004, a homeopath instructed one of her patients to stop taking conventional medication for a heart condition, advising her on June 22, 2004 to "Stop ALL medications including homeopathic", advising her on or around August 20 that she no longer needed to take her heart medication, and adding on August 23, "She just cannot take ANY drugs – I have suggested some homeopathic remedies ... I feel confident that if she follows the advice she will regain her health." The patient was admitted to hospital the next day, and died eight days later, the final diagnosis being "acute heart failure due to treatment discontinuation".

In 1978, Anthony Campbell, then a consultant physician at the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, criticized statements by George Vithoulkas claiming that syphilis, when treated with antibiotics, would develop into secondary and tertiary syphilis with involvement of the central nervous system, saying that "The unfortunate layman might well be misled by Vithoulkas' rhetoric into refusing orthodox treatment". Vithoulkas' claims echo the idea that treating a disease with external medication used to treat the symptoms would only drive it deeper into the body and conflict with scientific studies, which indicate that penicillin treatment produces a complete cure of syphilis in more than 90% of cases.

A 2006 review by W. Steven Pray of the College of Pharmacy at Southwestern Oklahoma State University recommends that pharmacy colleges include a required course in unproven medications and therapies, that ethical dilemmas inherent in recommending products lacking proven safety and efficacy data be discussed, and that students should be taught where unproven systems such as homeopathy depart from evidence-based medicine.

In an article entitled "Should We Maintain an Open Mind about Homeopathy?" published in the American Journal of Medicine, Michael Baum and Edzard Ernst – writing to other physicians – wrote that "Homeopathy is among the worst examples of faith-based medicine... These axioms are not only out of line with scientific facts but also directly opposed to them. If homeopathy is correct, much of physics, chemistry, and pharmacology must be incorrect...".

In 2013, Mark Walport, the UK Government Chief Scientific Adviser and head of the Government Office for Science, had this to say: "My view scientifically is absolutely clear: homoeopathy is nonsense, it is non-science. My advice to ministers is clear: that there is no science in homoeopathy. The most it can have is a placebo effect – it is then a political decision whether they spend money on it or not." His predecessor, John Beddington, referring to his views on homeopathy being "fundamentally ignored" by the Government, said: "The only one I could think of was homoeopathy, which is mad. It has no underpinning of scientific basis. In fact, all the science points to the fact that it is not at all sensible. The clear evidence is saying this is wrong, but homoeopathy is still used on the NHS."

Regulation and prevalence

Main article: Regulation and prevalence of homeopathy

Homeopathy is fairly common in some countries while being uncommon in others; is highly regulated in some countries and mostly unregulated in others. It is practised worldwide and professional qualifications and licences are needed in most countries. In some countries, there are no specific legal regulations concerning the use of homeopathy, while in others, licences or degrees in conventional medicine from accredited universities are required. In Germany, to become a homeopathic physician, one must attend a three-year training programme, while France, Austria and Denmark mandate licences to diagnose any illness or dispense of any product whose purpose is to treat any illness.

Some homeopathic treatment is covered by the public health service of several European countries, including France (phasing out coverage in 2021), Scotland, and Luxembourg. In England, the National Health Service recommends against prescribing homeopathic preparations, although in 2018 prescriptions worth £55,000 were written in defiance of the guidelines. However, this only represents less than 0.001% of the total NHS prescribing budget. On September 28, 2016 the UK's Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP) Compliance team wrote to homeopaths in the UK to "remind them of the rules that govern what they can and can't say in their marketing materials". The letter told homeopaths to "ensure that they do not make any direct or implied claims that homeopathy can treat medical conditions." and asks them to review their marketing communications "including websites and social media pages" to ensure compliance by November 3, 2016. The letter also includes information on sanctions in the event of non-compliance including, ultimately, "referral by the ASA to Trading Standards under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008".

In other countries, such as Belgium, homeopathy is not covered. In Austria, the public health service requires scientific proof of effectiveness in order to reimburse medical treatments and homeopathy is listed as not reimbursable, but exceptions can be made; private health insurance policies sometimes include homeopathic treatment. The Swiss government, after a 5-year trial, withdrew coverage of homeopathy and four other complementary treatments in 2005, stating that they did not meet efficacy and cost-effectiveness criteria, but following a referendum in 2009 the five therapies have been reinstated for a further 6-year trial period from 2012.

The Indian government recognizes homeopathy as one of its national systems of medicine; it has established AYUSH or the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. The south Indian state of Kerala also has a cabinet-level AYUSH department. The Central Council of Homoeopathy was established in 1973 to monitor higher education in homeopathy, and National Institute of Homoeopathy in 1975. A minimum of a recognized diploma in homeopathy and registration on a state register or the Central Register of Homoeopathy is required to practise homeopathy in India.

In February 2017, Russian Academy of Sciences declared homeopathy to be "dangerous pseudoscience" and "on a par with magic".

Public opposition

In the April 1997 edition of FDA Consumer, William T. Jarvis, the President of the National Council Against Health Fraud, said "Homeopathy is a fraud perpetrated on the public with the government's blessing, thanks to the abuse of political power of Sen. Royal S. Copeland ."

Mock "overdosing" on homeopathic preparations by individuals or groups in "mass suicides" have become more popular since James Randi began taking entire bottles of homeopathic sleeping pills before giving lectures. In 2010 The Merseyside Skeptics Society from the United Kingdom launched the 10:23 campaign, encouraging groups to publicly overdose as groups. In 2011 the 10:23 campaign expanded and saw sixty-nine groups participate; fifty-four submitted videos. In April 2012, at the Berkeley SkeptiCal conference, over 100 people participated in a mass overdose, taking coffea cruda, which is supposed to treat sleeplessness.

In 2011, the non-profit educational organizations Center for Inquiry (CFI) and the associated Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) have petitioned the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to initiate "rulemaking that would require all over-the-counter homeopathic drugs to meet the same standards of effectiveness as non-homeopathic drugs" and "to place warning labels on homeopathic drugs until such time as they are shown to be effective". In a separate petition, CFI and CSI request FDA to issue warning letters to Boiron, maker of Oscillococcinum, regarding their marketing tactic and criticize Boiron for misleading labelling and advertising of Oscillococcinum. In 2015, CFI filed comments urging the Federal Trade Commission to end the false advertising practice of homeopathy. On November 15, 2016, FTC declared that homeopathic products cannot include claims of effectiveness without "competent and reliable scientific evidence". If no such evidence exists, they must state this fact clearly on their labeling, and state that the product's claims are based only on 18th-century theories that have been discarded by modern science. Failure to do so will be considered a violation of the FTC Act. CFI in Canada is calling for persons that feel they were harmed by homeopathic products to contact them.

In July 2018 the Center for Inquiry filed a lawsuit against CVS for consumer fraud over its sale of homeopathic medicines. According to Nicholas Little, CFI's Vice President and General Counsel:

Homeopathy is a total sham, and CVS knows it. Yet the company persists in deceiving its customers about the effectiveness of homeopathic products. Homeopathics are shelved right alongside scientifically-proven medicines, under the same signs for cold and flu, pain relief, sleep aids, and so on. If you search for "flu treatment" on their website, it even suggests homeopathics to you, CVS is making no distinction between those products that have been vetted and tested by science, and those that are nothing but snake oil.

The filing in part contends that apart from being a waste of money, choosing homeopathic treatments to the exclusion of evidence-based medicines can result in worsened or prolonged symptoms, and in some cases, even death. It also claimed that CVS was selling homeopathic products on an easier-to-obtain basis than standard medication; for example on the CVS website Oscillococcinum could be purchased as a "Flu remedy", whereas the Tylenol brand could only be purchased by visiting a physical pharmacy. In May, 2019, CFI brought a similar lawsuit against Walmart for "committing wide-scale consumer fraud and endangering the health of its customers through its sale and marketing of homeopathic medicines".

In 2019, CFI also conducted a survey to assess the effects on consumer attitudes of having been informed about the lack of scientific evidence for the efficacy of the homeopathic remedies sold by Walmart and CVS. The survey found that "Exposure to the truth about the pseudoscience of homeopathy leads a large percentage of consumers to feel ripped off and deceived by the two largest drug retailers".

In August 2011, a class action lawsuit was filed against Boiron on behalf of "all California residents who purchased Oscillo at any time within the past four years". The lawsuit charged that it "is nothing more than a sugar pill", "despite falsely advertising that it contains an active ingredient known to treat flu symptoms". In March 2012, Boiron agreed to spend up to $12 million to settle the claims of falsely advertising the benefits of its homeopathic preparations.

In July 2012, CBC News reporter Erica Johnson for Marketplace conducted an investigation on the homeopathy industry in Canada; her findings were that it is "based on flawed science and some loopy thinking". Center for Inquiry (CFI) Vancouver skeptics participated in a mass overdose outside an emergency room in Vancouver, B.C., taking entire bottles of "medications" that should have made them sleepy, nauseous or dead; after 45 minutes of observation no ill effects were felt. Johnson asked homeopaths and company representatives about cures for cancer and vaccine claims. All reported positive results but none could offer any science backing up their statements, only that "it works". Johnson was unable to find any evidence that homeopathic preparations contain any active ingredient. Analysis performed at the University of Toronto's chemistry department found that the active ingredient is so small "it is equivalent to 5 billion times less than the amount of aspirin ... in a single pellet". Belladonna and ipecac "would be indistinguishable from each other in a blind test".

Homeopathic services offered at Bristol Homeopathic Hospital in the UK ceased in October 2015, partly in response to increased public awareness as a result of the 10:23 Campaign and a campaign led by the Good Thinking Society. University Hospitals Bristol confirmed that it would cease to offer homeopathic therapies from October 2015, at which point homeopathic therapies would no longer be included in the contract. Homeopathic services in the Bristol area were relocated to "a new independent social enterprise" at which Bristol Clinical Commissioning Group revealed "there are currently no (NHS) contracts for homeopathy in place." Following a threat of legal action by the Good Thinking Society campaign group, the British government has stated that the Department of Health will hold a consultation in 2016 regarding whether homeopathic treatments should be added to the NHS treatments blacklist (officially, Schedule 1 of the National Health Service (General Medical Services Contracts) (Prescription of Drugs etc.) Regulations 2004), that specifies a blacklist of medicines not to be prescribed under the NHS.

In March 2016, the University of Barcelona cancelled its master's degree in Homeopathy citing "lack of scientific basis", after advice from the Spanish Ministry of Health stated that "Homeopathy has not definitely proved its efficacy under any indication or concrete clinical situation". Shortly afterwards, in April 2016, the University of Valencia announced the elimination of its Masters in Homeopathy for 2017.

In June 2016, blogger and sceptic Jithin Mohandas launched a petition through Change.org asking the government of Kerala, India, to stop admitting students to homeopathy medical colleges. Mohandas said that government approval of these colleges makes them appear legitimate, leading thousands of talented students to join them and end up with invalid degrees. The petition asks that homeopathy colleges be converted to regular medical colleges and that people with homeopathy degrees be provided with training in scientific medicine.

In Germany, physician and critic of alternative medicine Irmgard Oepen was a relentless critic of homeopathy.

United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 2015 hearing

On April 20–21, 2015, the FDA held a hearing on homeopathic product regulation. Invitees representing the scientific and medical community, and various pro-homeopathy stakeholders, gave testimonials on homeopathic products and the regulatory role played by the FDA. Michael de Dora, a representative from the Center for Inquiry (CFI), on behalf of the organization and dozens of doctors and scientists associated with CFI and the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) gave a testimonial which summarized the basis of the organization's objection to homeopathic products, the harm that is done to the general public and proposed regulatory actions: