This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 157.91.111.161 (talk) at 20:52, 24 January 2005. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:52, 24 January 2005 by 157.91.111.161 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

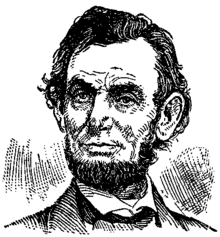

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809–April 15, 1865), sometimes called Abe Lincoln and nicknamed Honest Abe, the Rail Splitter, and the Great Emancipator, was the 16th (1861–1865) President of the United States, and the first president from the Republican Party.

The fghfghfghfghfghfgh election of Lincoln, who staunchly opposed the expansion of slavery, polarized the nation, and soon led to the Civil War. During the war, Lincoln assumed more power than any previous president in U.S. history. Taking a broad view of the president's war powers, he proclaimed a blockade, suspended the writ of habeas corpus for anti-Union activity, spent money without congressional authorization, and personally directed the war effort, which ultimately led the Union forces to victory over the rebel Confederacy.

Lincoln was an extremely deft politician who emerged as a wartime leader skilled at balancing competing considerations and adept at getting rival groups to work together toward a common goal. His leadership qualities were evident in his handling of the border slave states at the beginning of the fighting, in his defeat of a congressional attempt to reorganize his cabinet in 1862, and in his defusing of the peace issue in the 1864 presidential campaign.

Lincoln had a lasting influence on U.S. political institutions. The most important was setting the precedent of sweeping executive powers in a time of national emergency. Lincoln was also the president who declared Thanksgiving as a national holiday, established the U.S. Department of Agriculture (though not as a Cabinet-level department), revived national banking and banks, and admitted West Virginia and Nevada as states. His assassination, shortly after the end of the Civil War, made him a martyr to millions of Americans. His reputation was forever sealed by the victory that he won, but without the tarnishing that could have resulted from the disorder of Reconstruction in the aftermath of the war. He is widely considered to be the greatest U.S. president.

Early life

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a one-room log cabin on a farm in Hardin County, Kentucky (now in LaRue Co., in Nolin Creek, three miles (5 km) south of the town of Hodgenville), to Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. Lincoln was named after his deceased grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, who was killed by Native Americans. Lincoln's parents were largely uneducated. When Abraham Lincoln was seven years old, he and his parents moved to Spencer County, Indiana, "partly on account of slavery" and partly because of economic difficulty in Kentucky. In 1830, after economic and land-title difficulties in Indiana, the family settled on government land along the Sangamon River on a site selected by Lincoln's father in Macon County, Illinois, near the present city of Decatur. The following winter was especially brutal, and the family nearly moved back to Indiana. When his father relocated the family to a nearby site the following year, the 22-year-old Lincoln struck out on his own, canoeing down the Sangamon to homestead on his own in Sangamon County, Illinois (now in Menard County), in the village of New Salem. Later that year, hired by New Salem businessman Denton Offutt and accompanied by friends, he took goods from New Salem to New Orleans via flatboat on the Sangamon, Illinois and Mississippi rivers. While in New Orleans he may have witnessed a slave auction that left an indelible impression on him for the rest of his life.

Early political career and law practice

Lincoln began his political career in 1832 with a campaign for the Illinois General Assembly. The centerpiece of his platform was the undertaking of navigational improvements on the Sangamon in the hopes of attracting steamboat traffic to the river, which would allow sparsely populated, poor areas along and near the river to grow and prosper. He served as a captain in a company of the Illinois militia drawn from New Salem during the Black Hawk War, writing after being elected by his peers that he had not had "any such success in life which gave him so much satisfaction."

He later tried his hand at several business and political ventures, and failed at them. Finally, after coming across the second volume of Sir William Blackstone's four-volume Commentaries on the Laws of England, he taught himself the law, and was admitted to the Illinois Bar in 1837. That same year, he moved to Springfield, Illinois and began to practice law with Stephen T. Logan. Later, he partnered with Willam H. Herndon. He became one of the most highly respected and successful lawyers in the state of Illinois, and became steadily more prosperous. Lincoln served four successive terms in the Illinois House of Representatives, as a representative from Sangamon County, beginning in 1834. In 1837 he made his first protest against slavery in the Illinois House, stating that the institution was "founded on both injustice and bad policy."

Abraham Lincoln shared living quarters with Joshua Fry Speed from 1837 to 1841. Lincoln openly mentioned they shared a bed there, and they developed a life-long friendship. Some authors contend the relationship was sexual. See Abraham Lincoln's sexuality.

On November 4, 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd. President Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln had four sons.

- Robert Todd Lincoln : b. August 1, 1843 in Springfield, Illinois - d. July 26, 1926 in Manchester, Vermont.

- Edward Baker Lincoln : b. March 10, 1846 in Springfield, Illinois - d. February 1, 1850 in Springfield, Illinois

- William Wallace Lincoln : b. December 21, 1850 in Springfield, Illinois - d. February 20, 1862 in Washington, D.C.

- Thomas "Tad" Lincoln : b. April 4, 1853 in Springfield, Illinois - d. July 16, 1871 in Chicago, Illinois.

Only Robert survived into adulthood. Of Robert's children, only Jessie Lincoln had any children (2 - Mary Lincoln Beckwith and Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith). Neither Robert Beckwith nor Mary Beckwith had any children, so Abraham Lincoln's bloodline ended when Robert Beckwith (Lincoln's great-grandson) died on December 24, 1985.

In 1846 Lincoln was elected to one term in the House of Representatives as a member of the United States Whig Party. A staunch Whig, Lincoln often referred to Whig leader Henry Clay as his political idol. As a freshman House member, Lincoln was not a particularly powerful or influential figure in Congress. He used his office as an opportunity to speak out against the war with Mexico, which he attributed to President Polk's desire for "military glory -- that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood."

Lincoln was a key early supporter of Zachary Taylor's candidacy for the 1848 Whig Presidential nomination. When his term ended, the incoming Taylor administration offered him the governorship of the Oregon Territory. He declined, returning instead to Springfield, Illinois where, although remaining active in Whig Party affairs in the state, he turned most of his energies to making a living at the bar. By the mid-1850s, Lincoln had acquired prominence in Illinois legal circles, especially through his involvement in litigation involving competing transportation interests — both the river barges and the railroads.

Lincoln represented the Alton & Sangamon Railroad, for example, in an 1851 dispute with one of its shareholders, James A. Barret. Barret had refused to pay the balance on his pledge to that corporation on the ground that it had changed its originally planned route. Lincoln argued that as a matter of law a corporation is not bound by its original charter when that charter can be amended in the public interest, that the newer proposed Alton & Sangamon route was superior and less expensive, and that accordingly the corporation had a right to sue Mr. Barret for his delinquent payment. He won this case, and the decision by the Illinois Supreme Court was eventually cited by several other courts throughout the United States.

Another important example of Lincoln's skills as a railroad lawyer was a lawsuit over a tax exemption that the state granted to the Illinois Central Railroad. McLean County argued that the state had no authority to grant such an exemption, and it sought to impose taxes on the railroad notwithstanding. In January 1856, the Illinois Supreme Court delivered its opinion upholding the tax exemption, accepting Lincoln's arguments..

Toward the Presidency

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which expressly repealed the limits on slavery's spread that had been part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, helped draw Lincoln back into electoral politics. It was a speech against Kansas-Nebraska, on October 16, 1854 in Peoria, that caused Lincoln to stand out among the other free-soil orators of the day.

During his unsuccessful 1858 campaign for the United States Senate against Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln debated Douglas in a series of events which became a national discussion on the issues that were about to split the nation in two. Douglas, proposing popular sovereignty as the solution to the slavery impasse, had sponsored the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. During the debates, Lincoln forced Douglas to propose instead his Freeport Doctrine, which lost him further support among slave-holders. Though the Illinois state legislature chose Douglas as U.S. senator (this was before the 17th Amendment), Lincoln's eloquence during the campaign transformed him into a national political star.

Election and Early Presidency

The Lincoln-Douglas debates drew national attention to both men, leading to Lincoln becoming the Republican Party nominee for the Presidential election of 1860 against, among others, Douglas for the Northern Democrats. Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States, the first Republican to hold that office. Lincoln won entirely on the strength of his support in the North: he received no votes in nine states in the Deep South - not even on the ballot in some of them - and won only 2 of 996 counties in the entire South.

In response to Lincoln's election, seven slave states seceded before he took office, forming the Confederate States of America and greatly increasing tensions. President-elect Lincoln survived an assassination attempt in Baltimore, Maryland, and on February 23, 1861 arrived secretly in disguise to Washington, DC. Southerners ridiculed Lincoln for this subterfuge, but the efforts at security may have been prudent.

At Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, 1861, the Turners formed Lincoln's bodyguard; and a sizable garrison of federal troops was also present, ready to protect the president and the capital from rebel invasion. In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln declared, "I hold that in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments", arguing further that the purpose of the Constitution was "to form a more perfect union" than the Articles of Confederation which were explicitly perpetual, and thus the Constitution too was perpetual. He asked rhetorically that even were the Constitution construed as a simple contract, would it not require the agreement of all parties to rescind it? He also endorsed an amendment (which had already passed both houses) protecting slavery in those states in which it already existed.

After Union troops at Fort Sumter were fired on and forced to surrender in April, Lincoln called for more troops from each remaining state to recapture forts and preserve the Union. In response, four more slave states seceded by May 1861, and splinter factions from Missouri and Kentucky joined the Confederacy by December.

Lincoln on Slavery and Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln's actual position on freeing enslaved African-Americans is controversial today, despite the frequency and clarity with which he stated it both before his election to president (i.e. Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858) and after (see Lincoln's First Inaugural). Lincoln believed that blacks were entitled to "natural rights" as declared in the Declaration of Independence, and personally felt that slavery was a profound evil which should not spread westward. However, Lincoln maintained that the federal government did not possess the constitutional power to bar slavery in states where it already existed. See: Abraham Lincoln on slavery

Lincoln is often credited with freeing enslaved African-Americans with the Emancipation Proclamation, though in practice this only freed the slaves in areas of the Confederacy as those areas came under control of Union forces; in territories and states that still allowed slavery but had remained loyal to the Union, slaves were not initially freed. Lincoln signed the Proclamation as a wartime measure, insisting that only the outbreak of war gave constitutional power to the President to free slaves in states where it already existed. The proclamation made abolishing slavery in the rebel states an official war goal and it became the impetus for the enactment of the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution which abolished slavery. Politically, the Emancipation Proclamation did much to help the Northern cause; Lincoln's strong abolitionist stand finally convinced Britain and other countries that they could not support the South.

Sioux Uprising

Presented with 303 death warrants, Lincoln affirmed the execution of 39 convicted Santee Dakota men to death for their role in the "Sioux Uprising" of August 1862 in Minnesota (one was later reprieved). Lincoln was strongly chastised for this action in Minnesota and throughout his administration because many felt that all 303 Native Americans should have been executed. Reaction in Minnesota was so strong concerning Lincoln's kindness toward the Native Americans that Republicans lost their political strength in the state in 1864. Lincoln's response? "I could not afford to hang men for votes."

Civil War and Reconstruction

During the Civil War, Lincoln exercised powers no previous president had wielded; he suspended the writ of habeas corpus and frequently imprisoned accused Southern spies and sympathizers without trial. Some scholars have argued that Lincoln's political arrests extended to the highest levels of the government including an attempted warrant for Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, though the allegation remains unresolved and controversial (see the Taney Arrest Warrant controversy). On the other hand, he often commuted executions. The war was a source of constant frustration for the president, and it occupied nearly all of his time. After repeated difficulties with General George McClellan and a string of other unsuccessful commanding generals, Lincoln made the fateful decision to appoint a radical and somewhat scandalous army commander: General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant would apply his military knowledge and leadership talents to bring about the close of the Civil War.

Despite his meager education and “backwoods” upbringing, Lincoln possessed an extraordinary command of the English language, as evidenced by the Gettysburg Address, a speech dedicating a cemetery of Union soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. While most of the speakers—e.g. Edward Everett—at the event spoke at length, some for hours, Lincoln's few choice words resonated across the nation and across history, defying Lincoln's own prediction that "The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here." Lincoln's second inaugural address is also greatly admired and often quoted.

Lincoln was the only President to face a presidential election during a civil war (in 1864). The long war and the issue of emancipation appeared to be severely hampering his prospects and an electoral defeat appeared likely against the Democratic nominee and former general, George McClellan. Lincoln formed a Union party which composed of War democrats and republicans. However, a series of timely Union victories shortly before election day changed the situation dramatically and Lincoln was reelected.

The reconstruction of the Union weighed heavy on the President's mind. He was determined to take a course that would not permanently alienate the former Confederate states. "Let 'em up easy," he told his assembled military leaders Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Gen. William T. Sherman and Adm. David Dixon Porter in an 1865 meeting on the steamer River Queen. When Richmond, the Confederate capital, was at long last captured, Lincoln went there to make a public gesture of sitting at Jefferson Davis's own desk, symbolically saying to the nation that the President of the United States held authority over the entire land. He was greeted at the city as a conquering hero by freed slaves, whose sentiments were epitomized by one admirer's quote, "I know I am free for I have seen the face of Father Abraham and have felt him."

On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. This left only Joe Johnston's forces in the East to deal with both Sherman and Grant. Weeks later Johnston would defy Jefferson Davis and surrender his forces to Sherman. Of course, Lincoln would not survive to see the surrender of all Confederate forces; just days after Lee surrendered, Lincoln was assassinated.

Assassination

Lincoln had met frequently with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as the war drew to a close. The two men planned matters of reconstruction, and it was evident to all that they held each other in high regard. During their last meeting, on April 14, 1865 (Good Friday), Lincoln invited Grant to a social engagement that evening. Grant declined (Grant's wife, Julia Dent Grant, is said to have strongly disliked Mary Todd Lincoln).

Without the General and his wife, or his bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon, to whom he related his famous dream of his own assassination, the Lincolns left to attend a play at Ford's Theater. The play was Our American Cousin, a musical comedy by the British writer Tom Taylor (1817-1880). As Lincoln sat in the balcony, John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and Southern sympathizer from Maryland, crept up behind Lincoln in his state box and aimed a single-shot, round-slug .44 caliber Deringer at the President's head, firing at point-blank range. He shouted "Sic semper tyrannis!" (Latin: "Thus always to tyrants," and Virginia's state motto; some accounts say he added "The South is avenged!") and jumped from the balcony to the stage below.

Booth and several other conspirators had planned to kill a number of other government officials at the same time, but for various reasons Lincoln's was the only assassination actually carried out (although Secretary of State William H. Seward was badly injured by an assailant). Booth managed to limp to his horse and escape, and the mortally wounded president was taken to a house across the street, now called the Petersen House, where he lay in a coma for some time before he quietly expired.

Abraham Lincoln was officially pronounced dead at 7:22 AM the next morning, April 15, 1865 (Easter Saturday). Upon seeing him die, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton lamented either "Now he belongs to the angels" or "Now he belongs to the ages", the latter often repeated.

Booth and several of his conspirators were eventually captured, and either hanged or imprisoned. Booth himself was shot when discovered holed up in a barn (the barn itself collapsed in the 1930s and the site is now the median of a state highway in Virginia). Four people were tried by military tribunal and hanged for the assassination plot (David Herold, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell (aka Lewis Payne), and Mary Surratt, the first woman ever executed by the United States government.) Three people were sentenced to life imprisonment (Michael O'Laughlin, Samuel Arnold, and Dr. Samuel Mudd). Edward Spangler was sentenced to six years imprisonment. John Surratt, tried later by a civilian court, was acquitted. The fairness of the convictions, particularly of Mary Surratt, have been called into question, and there are doubts as to the exact degree of her involvement, if any, in the conspiracy.

Lincoln's body was carried by train in a grand funeral procession through several states on its way back to Illinois. The nation mourned a man whom many viewed as the savior of the United States, and protector and defender of what Lincoln himself called "the government of the people, by the people, and for the people."

Lincoln was buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, where a 177-foot-tall granite tomb surmounted with several bronze statues of Lincoln was constructed by 1874. Lincoln's wife and three of his four sons are also buried there (Robert is buried in Arlington National Cemetery). To prevent continued attempts to steal Lincoln's body and hold it for ransom, his son Robert Todd Lincoln had Lincoln exhumed and reinterred in concrete several feet thick on September 26, 1901. See Abraham Lincoln's Burial and Exhumation.

Lincoln memorialized

Lincoln has been memorialized in many city names, notably the capital of Nebraska; with the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC (illustrated, right); on the U.S. $5 bill and the 1 cent coin (Illinois is the primary opponent to the removal of the penny from circulation); and as part of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Lincoln's Tomb, Lincoln's Home in Springfield, New Salem, Illinois (a reconstruction of Lincoln's early adult hometown), Ford's Theater and Petersen House are all preserved as museums.

On February 12 1892 Abraham Lincoln's birthday was declared to be a federal holiday in the United States, though it was later combined with Washington's birthday in the form of President's Day. February 12 is still observed as a separate legal holiday in many states, including Illinois.

The statue of Lincoln that is furthest south is outside the USA - in Mexico. A gift from the United States, dedicated in 1966 by LBJ, it is a 13 foot high bronze statue in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico. The USA received a statue of Benito Juárez in exchange, which is in Washington, DC. Juárez and Lincoln exchanged friendly letters, and Mexico remembers Lincoln's opposition to the Mexican War. There are also at least two statues of Lincoln in England, one in London and another in Manchester .

The ballistic missile submarine Abraham Lincoln (SSBN-602) and the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) were named in his honor.

Presidential appointments

Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Abraham Lincoln | 1861–1865 |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin | 1861–1865 |

| Andrew Johnson | 1865 | |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Salmon P. Chase | 1861–1864 |

| William P. Fessenden | 1864–1865 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron | 1861–1862 |

| Edwin M. Stanton | 1862–1865 | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates | 1861–1864 |

| James Speed | 1864–1865 | |

| Postmaster General | Horatio King | 1861 |

| Montgomery Blair | 1861–1864 | |

| William Dennison | 1864–1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb B. Smith | 1861–1863 |

| John P. Usher | 1863–1865 | |

Supreme Court

Lincoln appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Noah Haynes Swayne - 1862

- Samuel Freeman Miller - 1862

- David Davis - 1862

- Stephen Johnson Field - 1863

- Salmon P. Chase - Chief Justice - 1864

Major presidential acts

- As President-elect

- As President

- Signed Revenue Act of 1861

- Signed Homestead Act

- Signed Morill Land-Grant College Act

- Established Bureau of Agriculture (1862)

- Signed National Banking Act of 1863

Trivia

- Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin were born on the same day, February 12, 1809.

- Lincoln's eldest child, Robert Todd Lincoln, had declined an invitation to be present at Ford's Theatre on the night his father was shot, had just arrived at the Washington train station where president James Garfield was shot (Robert Lincoln was in Garfield's cabinet), and had just arrived in Buffalo at the invitation of William McKinley when he was shot. Though he did not actually witness any of the three shootings, he declined any future presidential invitations.

- Lincoln's second child, Edward Baker, was named after close friend and Congressman Edward D. Baker.

Related articles

- Abraham Lincoln's Burial and Exhumation

- U.S. presidential election, 1860

- U.S. presidential election, 1864

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Lincoln-Kennedy coincidences

- List of U.S. Presidential religious affiliations

- World Almanac's Ten Most Influential People of the Second Millennium

Further reading

- Lincoln by David Herbert Donald ISBN 068482535X

- Lincoln Reconsidered: Essays on the Civil War Era by David Herbert Donald ISBN 0375725326

- Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President by Allen C. Guelzo ISBN 0802842933

- Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln by C. A. Tripp ISBN 0743266390

- Abraham Lincoln's DNA and other adventures in genetics by Philip Reilly (2000) ISBN 0879695803

- The Real Lincoln by Thomas DiLorenzo ISBN 0761526463

External links

- Mr. Lincoln's Virtual Library

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress (1850-1865)

- Abraham Lincoln's Program of Black Resettlement

- Abraham Lincoln Research Site

- Abraham Lincoln - Encarta

- Abraham Lincoln Online

- The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

- Especially for Students: An Overview of Abraham Lincoln's Life

- Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College

- Original 1860's Harper's Weekly Images and News on Abraham Lincoln

- The Lincoln Log: A Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln

- The Lincoln Museum

- John Summerfield Staples, President Lincoln's "Substitute"

- Documents at Project Gutenberg

- Gettysburg Address at Project Gutenberg

- Abraham Lincoln's First Inaugural Address at Project Gutenberg

- Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address at Project Gutenberg

- Lincoln Letters at Project Gutenberg

- Speeches and Letters of Abraham Lincoln, 1832-1865 at Project Gutenberg

- State of the Union Addresses at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Abraham Lincoln, the - Volume 1: 1832-1843 at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Abraham Lincoln, the - Volume 2: 1843-1858 at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Abraham Lincoln, the - Volume 3: the Lincoln-Douglas debates at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Abraham Lincoln, the - Volume 4: the Lincoln-Douglas debates at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Abraham Lincoln, the - Volume 5: 1858-1862 at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Abraham Lincoln, the - Volume 6: 1862-1863 at Project Gutenberg

- Writings of Abraham Lincoln, the - Volume 7: 1863-1865 at Project Gutenberg

- A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents: Volume 6, part 1: Abraham Lincoln at Project Gutenberg

- Lincoln's Yarns and Stories at Project Gutenberg

- Volume 1 and Volume 2 of Abraham Lincoln: a History (1890) by John Hay (1835-1905) & John George Nicolay (1832-1901)

- eText of The Boys' Life of Abraham Lincoln (1907) by Nicolay, Helen (1866-1954)

- eText of The Life of Abraham Lincoln (1901) by Henry Ketcham

- Volume 1 and Volume 2 of Abraham Lincoln (1899) by John T. Morse

- eText of The Every-day Life of Abraham Lincoln (1913) by Francis Fisher Browne

- eText of Abraham Lincoln: The People's Leader in the Struggle for National Existence (1909) by George Haven Putnam, Litt. D.

- eText of Lincoln's Personal Life (1999) by Nathaniel W. Stephenson

| Preceded byJohn Henry | U.S. Congressman from the 7th District of Illinois 1847-1849 |

Succeeded byThomas Langrell Harris |

| Preceded byJohn C. Frémont | Republican Party Presidential candidate 1860 (won) - 1864 (won) |

Succeeded byUlysses S. Grant |

| Preceded byJames Buchanan | President of the United States 1861–1865 |

Succeeded byAndrew Johnson |