This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Qualiesin (talk | contribs) at 15:56, 17 August 2020 (added Category:German resistance to Nazism using HotCat). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:56, 17 August 2020 by Qualiesin (talk | contribs) (added Category:German resistance to Nazism using HotCat)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| August Landmesser | |

|---|---|

| Born | 24 May 1910 (1910-05-24) Moorrege, Schleswig-Holstein, German Empire |

| Died | 17 October 1944 (1944-10-18) (aged 34) Ston, Croatia |

| Buried | A mass grave near Hodilje |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Deutsches Heer |

| Years of service | 1944–45 |

| Rank | Soldat |

| Unit | 999th Light Afrika Division |

| Battles / wars | World War II World War II in Yugoslavia |

| Spouse(s) | Irma Eckler (married 1935; marriage illegal under the Nuremberg Laws but retroactively legalized in 1951) |

| Children | 2 |

August Landmesser ([ˈaʊ̯ɡʊst ˈlantˌmɛsɐ]; 24 May 1910 – 17 October 1944) was a worker at the Blohm+Voss shipyard in Hamburg, Germany. He is known as the possible identity of a man appearing in a 1936 photograph, conspicuously refusing to perform the Nazi salute with the other workers. Landmesser had run afoul of the Nazi Party over his unlawful relationship with Irma Eckler, a Jewish woman. He was later imprisoned and eventually drafted into penal military service, where he was killed in action.

Biography

August Landmesser was born in Moorrege in 1910, the only child of August Franz Landmesser and Wilhelmine Magdalene (née Schmidtpott). In 1931, hoping it would help him get a job, he joined the Nazi Party. In 1935, when he became engaged to Irma Eckler (a Jewish woman), he was expelled from the party. They registered to be married in Hamburg, but the Nuremberg Laws enacted a month later prevented it. On 29 October 1935, Landmesser and Eckler's first daughter, Ingrid, was born.

In 1937, Landmesser and Eckler tried to flee to Denmark but were apprehended. She was again pregnant, and he was charged and found guilty in July 1937 of "dishonoring the race" under Nazi racial laws. He argued that neither he nor Eckler knew that she was fully Jewish, and was acquitted on 27 May 1938 for lack of evidence, with the warning that a repeat offense would result in a multi-year prison sentence. The couple publicly continued their relationship, and on 15 July 1938 he was arrested again and sentenced to two and a half years in the Börgermoor concentration camp.

Eckler was detained by the Gestapo and held at the prison Fuhlsbüttel, where she gave birth to a second daughter, Irene. From there she was sent to the Oranienburg concentration camp, the Lichtenburg concentration camp for women, and then the women's concentration camp at Ravensbrück. A few letters came from Irma Eckler until January 1942. It is believed that she was taken to the Bernburg Euthanasia Centre in February 1942, where she was among the 14,000 murdered; in the course of post-war documentation, in 1949 she was pronounced legally dead, with a date of 28 April 1942.

Meanwhile, Landmesser was discharged from prison on 19 January 1941. He worked as a foreman for the haulage company Püst. The company had a branch at the Heinkel-Werke (factory) in Warnemünde. In February 1944 he was drafted into a penal battalion, the 999th Fort Infantry Battalion. He was declared killed in action, after fighting in Croatia on 17 October 1944. Like Eckler, he was legally declared dead in 1949.

Their children were initially taken to the city orphanage. Ingrid was later allowed to live with her maternal grandmother while Irene went to the home of foster parents in 1941. Ingrid was also placed with foster parents after her grandmother's death in 1953.

The marriage of August Landmesser and Irma Eckler was recognized retroactively by the Senate of Hamburg in the summer of 1951, and in the autumn of that year Ingrid assumed the surname Landmesser. Irene continued to use the surname Eckler.

Recognition

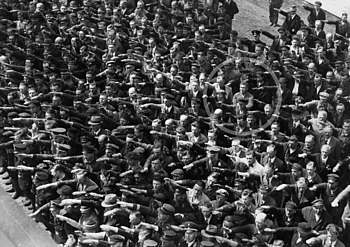

A figure identified by Irene Eckler as August Landmesser is visible in a photograph taken on 13 June 1936, which was published on 22 March 1991 in Die Zeit. It shows a large gathering of workers at the Blohm+Voss shipyard in Hamburg, for the launching of the navy training ship Horst Wessel. Almost everyone in the image has raised his arm in the Nazi salute, with the most obvious exception of a man toward the back of the crowd, who grimly stands with his arms crossed over his chest.

In 1996, Irene Eckler published Die Vormundschaftsakte 1935–1958: Verfolgung einer Familie wegen "Rassenschande" (The Guardianship Documents 1935–1958: Persecution of a Family for "Racial Disgrace"). The book tells the story of her family, and includes a large number of original documents from the time in question, including letters from her mother and documents from state institutions.

The identity of the man in the photograph is not known with certainty. Another family claims it is Gustav Wegert (1890–1959), a metalworker at Blohm+Voss who habitually refused to salute on religious grounds. They have presented documentation of Wegert's employment at Blohm+Voss at that time, and family photos which resemble the man in the famous photo, as evidence of their claim.

References

- "The Man who defied Hitler died in Yugoslavia". 16 January 2017.

- Straße, Amanda. "Verbotene Liebe | Courage". Fasena.de. 1&1 Internet. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Simone Erpel: Zivilcourage : Schlüsselbild einer unvollendeten "Volksgemeinschaft". In: Gerhard Paul (Hrsg.): Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, Bd. 1: 1900–1949, Göttingen 2009, pp. 490–497, ISBN 978-3-89331-949-7.

- Eckler, Irene (4 July 1998). "A family torn apart by "Rassenschande": political persecution in the Third Reich ; documents and reports from Hamburg in German and English". Horneburg – via Google Books.

- ^ Roux, François (6 June 2013). Comprendre Hitler et les allemands. Paris, France: Éditions Max Milo. ISBN 9782315004614. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Flock, Elizabeth (7 February 2012). "August Landmesser, shipyard worker in Hamburg, refused to perform Nazi salute (photo)". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Washington Post Media. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Straße, Amanda. "Father reported missing". Fasena.de. 1&1 Internet. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Bartrop, Paul R. (2016). Resisting the Holocaust: Upstanders, Partisans, and Survivors. ABC-CLIO. p. 152. ISBN 9781610698795.

- Eckler, Irene (1996). Die Vormundschaftsakte 1935–1958: Verfolgung einer Familie wegen "Rassenschande": Dokumente und Berichte aus Hamburg. Horneburg. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- "Photo of the Day". Whale Oil Beef Hooked | Whaleoil Media. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Gerhard Paul, Das Jahrhundert der Bilder 1900 bis 1949, Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2009, Seite 494 rechte Spalte Absatz 3), as quoted in . Quote: "In the meantime another Family from Hamburg has identified the man as a relative. It should be Gustav Wegert (1890–1959) who worked as a metalworker at Blohm & Voss. As a believing Christian he generally refused the Nazi Salute. Despite his distance to the Nazi Regime Gustav Wegert did not get in the eye of the Nazi persecution administration. Portraits from Wegert and Landmesser prove in both cases great similarity with the worker on that picture. At this time it has to remain unsettled who the man in the picture is“.

- "1936 – Just one refused the Nazi salute". wegert-familie.de.

- "The German Non-Saluter Myth – Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog". 26 October 2014.

- Brajovic, Predrag (21 April 2018). "Mr. Wegert and Mr. Landmesser: People, Numbers and the Tipping Point". Medium. Retrieved 1 July 2020.