This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sweetpool50 (talk | contribs) at 18:41, 20 September 2020 (→Modern usage: deleted section of doubtful relevance and largely sourced, per 2017 template). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:41, 20 September 2020 by Sweetpool50 (talk | contribs) (→Modern usage: deleted section of doubtful relevance and largely sourced, per 2017 template)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the English nursery rhyme. For the film, see Old King Cole (film). For other uses, see King Cole (disambiguation). British nursery rhyme| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Old King Cole" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| "Old King Cole" | |

|---|---|

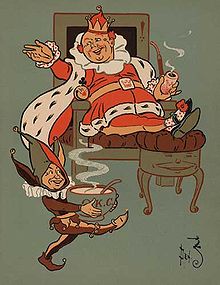

Illustration by William Wallace Denslow Illustration by William Wallace Denslow | |

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Published | 1708-9 |

"Old King Cole" is a British nursery rhyme first attested in 1708. Though there is much speculation about the identity of King Cole, it is unlikely that he can be identified reliably as any historical figure. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 1164. The poem describes a merry king who called for his pipe, bowl, and musicians, with the details varying among versions.

The "bowl" is a drinking vessel, while it is unclear whether the "pipe" is a musical instrument or a pipe for smoking tobacco.

Lyrics

The most common modern version of the rhyme is:

Old King Cole was a merry old soul,

And a merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe, and he called for his bowl,

And he called for his fiddlers three.

Every fiddler he had a fiddle,

And a very fine fiddle had he;

Oh there's none so rare, as can compare,

With King Cole and his fiddlers three.

The song is first attested in William King's Useful Transactions in Philosophy in 1708–9.

King's version has the following lyrics:

Good King Cole,

And he call'd for his Bowle,

And he call'd for Fidler's three;

And there was Fiddle, Fiddle,

And twice Fiddle, Fiddle,

For 'twas my Lady's Birth-day,

Therefore we keep Holy-day

And come to be merry.

Identity of King Cole

There is much speculation about the identity of King Cole, but it is unlikely that he can be identified reliably given the centuries between the attestation of the rhyme and the putative identities; none of the extant theories is well supported.

William King mentions two possibilities: the "Prince that Built Colchester" and a 12th-century cloth merchant from Reading named Cole-brook. Sir Walter Scott thought that "Auld King Coul" was Cumhall, the father of the giant Fyn M'Coule (Finn McCool). Other modern sources suggest (without much justification) that he was Richard Cole (1568–1614) of Bucks in the parish of Woolfardisworthy on the north coast of Devon, whose monument and effigy survive in All Hallows Church, Woolfardisworthy.

Coel Hen theory

It is often noted that the name of the legendary Welsh king Coel Hen can be translated 'Old Cole' or 'Old King Cole'. This sometimes leads to speculation that he, or some other Coel in Roman Britain, is the model for Old King Cole of the nursery rhyme. However, there is no documentation of a connection between the fourth-century figures and the eighteenth-century nursery rhyme. There is also a dubious connection of Old King Cole to Cornwall and King Arthur found at Tintagel Castle that there was a Cornish King or Lord Coel.

Further speculation connects Old King Cole and thus Coel Hen to Colchester, but in fact Colchester was not named for Coel Hen. Connecting with the musical theme of the nursery rhyme, according to a much later source, Coel Hen supposedly had a daughter who was skilled in music, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, writing in the 12th century.

Cole-brook theory

In the 19th century William Chappell, an expert on popular music, suggested the possibility that the "Old King Cole" was really "Old Cole", alias Thomas Cole-brook, a supposed 12th-century Reading cloth merchant whose story was recounted by Thomas Deloney in his Pleasant History of Thomas of Reading (c. 1598), and who was well known as a character in plays of the early 17th century. The name "Old Cole" had some special meaning in Elizabethan theatre, but it is unclear what it was.

Notes

- ^ I. Opie and P. Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 156–8.

- North Devon and Exmoor Seascape Character Assessment, November 2015

- Alistair Moffat, The Borders: A History of the Borders from Earliest Times, ISBN 1841584665 (unpaginated)

- Anthony Richard Birley, The People of Roman Britain, ISBN 0520041194, p. 160

- Albert Jack, Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes, ISBN 0399535551, s.v. 'Old King Cole'

- see Opie and Opie, and discussion at Colchester#Name

References

- Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1136). History of the Kings of Britain.

- Huntingdon, Henry of (c. 1129), Historia Anglorum.

- Kightley, C (1986), Folk Heroes of Britain. Thames & Hudson.

- Morris, John. The Age of Arthur: A History of the British Isles from 350 to 650. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973. ISBN 978-0-684-13313-3.

- Opie, I & P (1951), The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. Oxford University Press.

- Skene, WF (1868), The Four Ancient Books of Wales. Edmonston & Douglas.

- Legendary British kings

- Fictional kings

- Northern Brythonic monarchs

- English folklore

- 4th-century monarchs in Europe

- 3rd-century monarchs in Europe

- English folk songs

- English children's songs

- Traditional children's songs

- 1708 works

- 1708 in England

- English nursery rhymes

- Cumulative songs

- Songs about royalty

- Songs about fictional male characters