This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) at 06:30, 5 November 2020 (if there is a failure to achieve the 270 votes, contingent processes come into play). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 06:30, 5 November 2020 by Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) (if there is a failure to achieve the 270 votes, contingent processes come into play)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the electoral college of the United States. For electoral colleges in general, see Electoral college. For other uses and regions, see Electoral college (disambiguation). Institution that officially elects both the President and Vice President of the United States

The Electoral College of the United States refers to the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of electing the president and vice president. Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 provides that each state shall appoint electors selected in a manner determined by its legislature, and it disqualifies any person holding a federal office, either elected or appointed, from being an elector. There are currently 538 electors, and an absolute majority of electoral votes—270 or more—is required for it to elect the president and vice president. Currently, all states (and the District of Columbia) use a statewide popular vote on Election Day, on the first Tuesday after November 1. All jurisdictions use a winner-take-all method to assign their electoral votes, with the exceptions of Maine and Nebraska, which use a one-elector-per-district method in combination with winner-takes-all (for two electors). The electors meet and vote in December and the president is inaugurated in January.

The appropriateness of the Electoral College system is a matter of ongoing debate. Supporters argue that it is a fundamental component of American federalism. They maintain the system elected the winner of the nationwide popular vote in over 90% of presidential elections; promotes political stability; preserves the Constitutional role of the states in presidential elections; and fosters a broad-based, enduring, and generally moderate political party system.

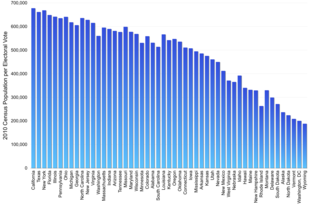

Critics argue that the Electoral College is less democratic than a national direct popular vote and is subject to manipulation because of faithless electors; that the system is antithetical to a democracy that strives for a standard of "one person, one vote"; and that there can be elections where one candidate wins the national popular vote but another wins the electoral vote and therefore the presidency, as in 2000 and 2016. Individual citizens in less populous states have proportionately more voting power than those in more populous states. Furthermore, candidates can win by focusing their resources on just a few swing states.

Number of electors

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution, empowers each state legislature to determine the manner by which the state's electors are chosen. The Electors in (chosen by) each state are the same quantity as the state's Congressmen (members of the House of Representatives and two Senators).

There are currently 538 electors as there are 100 senators and 435 state representatives. The reason for the disparity of three is the Twenty-third Amendment. Ratified in 1961, it provides that the District established pursuant to Article I, Section 8 as the seat of the federal government (namely, District of Columbia) is entitled to the number of Electors it would have if it was a state, but in no case more than that of the least populous state. In practice, that results in Washington D.C. being entitled to 3 electors.

U.S. territories (for example, modern-day U.S. territories like Puerto Rico and historical U.S. territories like Dakota Territory) have never been entitled to any electors in the U.S. Electoral College.

Procedure

Following the national presidential election day (on the first Tuesday after November 1), each state counts its popular votes according to its laws to select the electors.

In 48 states and Washington, D.C., the winner of the plurality of the statewide vote receives all of that state's electors; in Maine and Nebraska, two electors are assigned in this manner and the remaining electors are allocated based on the plurality of votes in each congressional district. States generally require electors to pledge to vote for that state's winner; to avoid faithless electors, most states have adopted various laws to enforce the electors’ pledge.

The electors of each state meet in their respective state capital on the first Monday after the second Wednesday of December to cast their votes. The results are counted by Congress, where they are tabulated in the first week of January before a joint meeting of the Senate and House of Representatives, presided over by the vice president, as president of the Senate. Should a majority of votes not be cast for a candidate, the House turns itself into a presidential election session, where one vote is assigned to each of the fifty states. Similarly, the Senate is responsible for electing the vice president, with each senator having one vote. The elected president and vice president are inaugurated on January 20.

Background

The Constitutional Convention in 1787 used the Virginia Plan as the basis for discussions, as the Virginia proposal was the first. The Virginia Plan called for Congress to elect the president. Delegates from a majority of states agreed to this mode of election. After being debated, however, delegates came to oppose nomination by Congress for the reason that it could violate the separation of powers. James Wilson then made a motion for electors for the purpose of choosing the president.

Later in the convention, a committee formed to work out various details including the mode of election of the president, including final recommendations for the electors, a group of people apportioned among the states in the same numbers as their representatives in Congress (the formula for which had been resolved in lengthy debates resulting in the Connecticut Compromise and Three-Fifths Compromise), but chosen by each state "in such manner as its Legislature may direct". Committee member Gouverneur Morris explained the reasons for the change; among others, there were fears of "intrigue" if the president were chosen by a small group of men who met together regularly, as well as concerns for the independence of the president if he were elected by Congress.

However, once the Electoral College had been decided on, several delegates (Mason, Butler, Morris, Wilson, and Madison) openly recognized its ability to protect the election process from cabal, corruption, intrigue, and faction. Some delegates, including James Wilson and James Madison, preferred popular election of the executive. Madison acknowledged that while a popular vote would be ideal, it would be difficult to get consensus on the proposal given the prevalence of slavery in the South:

There was one difficulty, however of a serious nature attending an immediate choice by the people. The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States; and the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of Negroes. The substitution of electors obviated this difficulty and seemed on the whole to be liable to the fewest objections.

The Convention approved the Committee's Electoral College proposal, with minor modifications, on September 6, 1787. Delegates from states with smaller populations or limited land area, such as Connecticut, New Jersey, and Maryland, generally favored the Electoral College with some consideration for states. At the compromise providing for a runoff among the top five candidates, the small states supposed that the House of Representatives, with each state delegation casting one vote, would decide most elections.

In The Federalist Papers, James Madison explained his views on the selection of the president and the Constitution. In Federalist No. 39, Madison argued that the Constitution was designed to be a mixture of state-based and population-based government. Congress would have two houses: the state-based Senate and the population-based House of Representatives. Meanwhile, the president would be elected by a mixture of the two modes.

Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 68 laid out what he believed were the key advantages to the Electoral College. The electors come directly from the people and them alone, for that purpose only, and for that time only. This avoided a party-run legislature or a permanent body that could be influenced by foreign interests before each election. Hamilton explained that the election was to take place among all the states, so no corruption in any state could taint "the great body of the people" in their selection. The choice was to be made by a majority of the Electoral College, as majority rule is critical to the principles of republican government. Hamilton argued that electors meeting in the state capitals were able to have information unavailable to the general public. Hamilton also argued that since no federal officeholder could be an elector, none of the electors would be beholden to any presidential candidate.

Another consideration was that the decision would be made without "tumult and disorder", as it would be a broad-based one made simultaneously in various locales where the decision makers could deliberate reasonably, not in one place where decision makers could be threatened or intimidated. If the Electoral College did not achieve a decisive majority, then the House of Representatives was to choose the president from among the top five candidates, ensuring selection of a presiding officer administering the laws would have both ability and good character. Hamilton was also concerned about somebody unqualified but with a talent for "low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity" attaining high office.

Additionally, in the Federalist No. 10, James Madison argued against "an interested and overbearing majority" and the "mischiefs of faction" in an electoral system. He defined a faction as "a number of citizens whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." A republican government (i.e., representative democracy, as opposed to direct democracy) combined with the principles of federalism (with distribution of voter rights and separation of government powers), would countervail against factions. Madison further postulated in the Federalist No. 10 that the greater the population and expanse of the Republic, the more difficulty factions would face in organizing due to such issues as sectionalism.

Although the United States Constitution refers to "Electors" and "electors", neither the phrase "Electoral College" nor any other name is used to describe the electors collectively. It was not until the early 19th century that the name "Electoral College" came into general usage as the collective designation for the electors selected to cast votes for president and vice president. The phrase was first written into federal law in 1845, and today the term appears in 3 U.S.C. § 4, in the section heading and in the text as "college of electors".

History

Initially, state legislatures chose the electors in many of the states. From the early 19th century, states progressively changed to selection by popular election. In 1824, there were six states in which electors were still legislatively appointed. By 1832, only South Carolina had not transitioned. Since 1880, electors in every state have been chosen based on a popular election held on Election Day. The popular election for electors means the president and vice president are in effect chosen through indirect election by the citizens.

Since the mid-19th century, when all electors have been popularly chosen, the Electoral College has elected the candidate who received the most popular votes nationwide, except in four elections: 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016. In 1824, when there were six states in which electors were legislatively appointed, rather than popularly elected, the true national popular vote is uncertain. The electors failed to select a winning candidate, so the matter was decided by the House of Representatives.

Original plan

Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 of the Constitution provided the original plan by which the electors voted for president. Under the original plan, each elector cast two votes for president; electors did not vote for vice president. Whoever received a majority of votes from the electors would become president, with the person receiving the second most votes becoming vice president.

The original plan of the Electoral College was based upon several assumptions and anticipations of the Framers of the Constitution:

- Choice of the president should reflect the "sense of the people" at a particular time, not the dictates of a faction in a "pre-established body" such as Congress or the State legislatures, and independent of the influence of "foreign powers".

- The choice would be made decisively with a "full and fair expression of the public will" but also maintaining "as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder".

- Individual electors would be elected by citizens on a district-by-district basis. Voting for president would include the widest electorate allowed in each state.

- Each presidential elector would exercise independent judgment when voting, deliberating with the most complete information available in a system that over time, tended to bring about a good administration of the laws passed by Congress.

- Candidates would not pair together on the same ticket with assumed placements toward each office of president and vice president.

Election expert, William C. Kimberling, reflected on the original intent as follows:

"The function of the College of Electors in choosing the president can be likened to that in the Roman Catholic Church of the College of Cardinals selecting the Pope. The original idea was for the most knowledgeable and informed individuals from each State to select the president based solely on merit and without regard to State of origin or political party."

Furthermore, the original intention of the framers was that the Electors would not feel bound to support any particular candidate, but would vote their conscience, free of external pressure. Chief Justice Robert Jackson wrote,

"No one faithful to our history can deny that the plan originally contemplated, what is implicit in its text, that electors would be free agents, to exercise an independent and nonpartisan judgment as to the men best qualified for the Nation's highest offices."

Breakdown and revision

The emergence of political parties and nationally coordinated election campaigns soon complicated matters in the elections of 1796 and 1800. In 1796, Federalist Party candidate John Adams won the presidential election. Finishing in second place was Democratic-Republican Party candidate Thomas Jefferson, the Federalists' opponent, who became the vice president. This resulted in the president and vice president being of different political parties.

In 1800, the Democratic-Republican Party again nominated Jefferson for president and also nominated Aaron Burr for vice president. After the electors voted, Jefferson and Burr were tied with one another with 73 electoral votes each. Since ballots did not distinguish between votes for president and votes for vice president, every ballot cast for Burr technically counted as a vote for him to become president, despite Jefferson clearly being his party's first choice. Lacking a clear winner by constitutional standards, the election had to be decided by the House of Representatives pursuant to the Constitution's contingency election provision.

Having already lost the presidential contest, Federalist Party representatives in the lame duck House session seized upon the opportunity to embarrass their opposition by attempting to elect Burr over Jefferson. The House deadlocked for 35 ballots as neither candidate received the necessary majority vote of the state delegations in the House (The votes of nine states were needed for a conclusive election.). On the 36th ballot, Delaware's lone Representative, James A. Bayard, made it known that he intended to break the impasse for fear that failure to do so could endanger the future of the Union. Bayard and other Federalists from South Carolina, Maryland, and Vermont abstained, breaking the deadlock and giving Jefferson a majority.

Responding to the problems from those elections, Congress proposed on December 9, 1803, and three-fourths of the states ratified by June 15, 1804, the Twelfth Amendment. Starting with the 1804 election, the amendment requires electors cast separate ballots for president and vice president, replacing the system outlined in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3.

Evolution to the general ticket

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution states:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

Alexander Hamilton described the Founding Fathers' view of how electors would be chosen:

A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated ... They have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men , who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes ; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment. And they have EXCLUDED from eligibility to this trust, all those who from situation might be suspected of too great devotion to the President in office ... Thus without corrupting the body of the people, the immediate agents in the election will at least enter upon the task free from any sinister bias . Their transient existence, and their detached situation, already taken notice of, afford a satisfactory prospect of their continuing so, to the conclusion of it."

They intended that this would take place district by district. The district plan was carried out by some states until 1892. For example, in Massachusetts in 1820, the rule stated "the people shall vote by ballot, on which shall be designated who is voted for as an Elector for the district." In other words, the name of a candidate for president was not on the ballot. Instead citizens voted for their local elector, whom they trusted later to cast a responsible vote for president.

Some state leaders began to adopt the strategy that the favorite partisan presidential candidate among the people in their state would have a much better chance if all of the electors selected by their state were sure to vote the same way—a "general ticket" of electors pledged to a party candidate. So the slate of electors chosen by the state were no longer free agents, independent thinkers, or deliberative representatives. They became, as Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote, "voluntary party lackeys and intellectual non-entities." Though this was indisputably in violation of the concepts Hamilton articulated in the Federalist #68, once one state took that strategy, the others felt compelled to follow suit in order to compete for the strongest influence on the election.

When James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, two of the most important architects of the Electoral College, saw this strategy being taken by some states, they protested strongly. Madison and Hamilton both made it clear this approach violated the spirit of the Constitution. According to Hamilton, the selection of the president should be "made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station ." Hamilton stated that the electors were to analyze the list of potential presidents and select the best one. He also used the term "deliberate." Hamilton considered a pre-pledged elector in violation of the spirit of Article II of the Constitution insofar as such electors could make no "analysis" or "deliberate" concerning the candidates. Madison agreed entirely, saying that when the Constitution was written, all of its authors assumed individual electors would be elected in their districts, and it was inconceivable that a "general ticket" of electors dictated by a state would supplant the concept. Madison wrote to George Hay:

The district mode was mostly, if not exclusively in view when the Constitution was framed and adopted; & was exchanged for the general ticket .

The Founding Fathers intended that each elector would be elected by the citizens of a district, and that elector was to be free to analyze and deliberate regarding who is best suited to be president.

Each state government was free to have its own plan for selecting its electors, and the Constitution does not explicitly require states to popularly elect their electors. However, Federalist #68, insofar as it reflects the intent of the founders, states that Electors will be "selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass," and with regard to choosing Electors, "they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America." In spite of Hamilton's perspective, several methods for selecting electors are described below.

Madison and Hamilton were so upset by what they saw as a distortion of the original intent that they advocated a constitutional amendment to prevent anything other than the district plan: "the election of Presidential Electors by districts, is an amendment very proper to be brought forward," Madison told George Hay in 1823. Hamilton drafted an amendment to the Constitution mandating the district plan for selecting electors. However, Hamilton's untimely death in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804 prevented him from advancing his proposed reforms any further. Madison also drafted a constitutional amendment that would insure the original "district" plan of the framers. Jefferson agreed with Hamilton and Madison saying, "all agree that an election by districts would be the best." Jefferson explained to Madison's correspondent why he was doubtful of the amendment being ratified: "the states are now so numerous that I despair of ever seeing another amendment of the constitution."

Evolution of selection plans

In 1789, the at-large popular vote, the winner-take-all method, began with Pennsylvania and Maryland. Massachusetts, Virginia and Delaware used a district plan by popular vote, and state legislatures chose in the five other states participating in the election (Connecticut, Georgia, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and South Carolina). New York, North Carolina and Rhode Island did not participate in the election. New York's legislature deadlocked and abstained; North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution.

By 1800, Virginia and Rhode Island voted at large; Kentucky, Maryland, and North Carolina voted popularly by district; and eleven states voted by state legislature. Beginning in 1804 there was a definite trend towards the winner-take-all system for statewide popular vote.

By 1832, only South Carolina legislatively chose its electors, and it abandoned the method after 1860. Maryland was the only state using a district plan, and from 1836 district plans fell out of use until the 20th century, though Michigan used a district plan for 1892 only. States using popular vote by district have included ten states from all regions of the country.

Since 1836, statewide winner-take-all popular voting for electors has been the almost universal practice. Currently, Maine (since 1972) and Nebraska (since 1996) use the district plan, with two at-large electors assigned to support the winner of the statewide popular vote.

Three-fifths clause and the role of slavery

After the initial estimates agreed to in the original Constitution, Congressional and Electoral College reapportionment was made according to a decennial census to reflect population changes, modified by counting three-fifths of slaves. On this basis after the first census, the Electoral College still gave the free men of slave-owning states (but never slaves) extra power (Electors) based on a count of these disenfranchised people, in the choice of the U.S. president.

At the Constitutional Convention, the College composition in theory amounted to 49 votes for northern states (in the process of abolishing slavery) and 42 for slave-holding states (including Delaware). In the event, the first (i.e. 1788) presidential election lacked votes and electors for unratified Rhode Island (3) and North Carolina (7) and for New York (8) which reported too late; the Northern majority was 38 to 35. For the next two decades the three-fifths clause led to electors of free-soil Northern states numbering 8% and 11% more than Southern states. The latter had, in the compromise, relinquished counting two-fifths of their slaves and, after 1810, were outnumbered by 15.4% to 23.2%.

While House members for Southern states were boosted by an average of 1⁄3, a free-soil majority in the College maintained over this early republic and Antebellum period. Scholars further conclude that the three-fifths clause had low impact on sectional proportions and factional strength, until denying the North a pronounced supermajority, as to the Northern, federal inititive to abolish slavery. The seats that the South gained from such "slave bonus" were quite evenly distributed between the parties. In the First Party System (1795–1823), the Jefferson Republicans gained 1.1 percent more adherents from the slave bonus, while the Federalists lost the same proportion. At the Second Party System (1823–1837) the emerging Jacksonians gained just 0.7% more seats, versus the opposition loss of 1.6%.

The three-fifths slave-count rule is associated with three or four outcomes, 1792–1860:

- The clause, having reduced the South's power, led to John Adams's win in 1796 over Thomas Jefferson.

- In 1800, historian Garry Wills argues, Jefferson's victory over Adams was due to the slave bonus count in the Electoral College as Adams would have won if citizens' votes were used for each state. However, historian Sean Wilentz points out that Jefferson's purported "slave advantage" ignores an offset by electoral manipulation by anti-Jefferson forces in Pennsylvania. Wilentz concludes that it is a myth to say that the Electoral College was a pro-slavery ploy.

- In 1824, the presidential selection was passed to the House of Representatives, and John Quincy Adams was chosen over Andrew Jackson, who won fewer citizens' votes. Then Jackson won in 1828, but would have lost if the College were citizen-only apportionment. Scholars conclude that in the 1828 race, Jackson benefited materially from the Three-fifths clause by providing his margin of victory.

The first "Jeffersonian" and "Jacksonian" victories were of great import as they ushered in sustained party majorities of several Congresses and presidential party eras.

Besides the Constitution prohibiting Congress from regulating foreign or domestic slave trade before 1808 and a duty on states to return escaped "persons held to service", legal scholar Akhil Reed Amar argues that the College was originally advocated by slaveholders as a bulwark to prop up slavery. In the Congressional apportionment provided in the text of the Constitution with its Three-Fifths Compromise estimate, "Virginia emerged as the big winner more than a quarter of the needed to win an election in the first round ." Following the 1790 census, the most populous state in the 1790 Census was Virginia, with 39.1% slaves, or 292,315 counted three-fifths, to yield a calculated number of 175,389 for congressional apportionment. "The "free" state of Pennsylvania had 10% more free persons than Virginia but got 20% fewer electoral votes." Pennsylvania split eight to seven for Jefferson, favoring Jefferson with a majority of 53% in a state with 0.1% slave population. Historian Eric Foner agrees the Constitution's Three-Fifths Compromise gave protection to slavery.

Supporters of the College have provided many counterarguments to the charges that it defended slavery. Abraham Lincoln, the president who helped abolish slavery, won a College majority in 1860 despite winning 39.8% of citizen's votes. This, however, was a clear plurality of a popular vote divided among four main candidates.

Benner notes that Jefferson's first margin of victory would have been wider had the entire slave population been counted on a per capita basis. He also notes that some of the most vociferous critics of a national popular vote at the constitutional convention were delegates from free states, including Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, who declared that such a system would lead to a "great evil of cabal and corruption," and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, who called a national popular vote "radically vicious". Delegates Oliver Ellsworth and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, a state which had adopted a gradual emancipation law three years earlier, also criticized a national popular vote. Of like view was Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a member of Adams' Federalist Party, presidential candidate in 1800. He hailed from South Carolina and was a slaveholder. In 1824, Andrew Jackson, a slaveholder from Tennessee, was similarly defeated by John Quincy Adams, a strong critic of slavery.

Fourteenth Amendment

Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment requires a state's representation in the House of Representatives to be reduced if the state denies the right to vote to any male citizen aged 21 or older, unless on the basis of "participation in rebellion, or other crime". The reduction is to be proportionate to such people denied a vote. This amendment refers to "the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States" (among other elections). It is the only part of the Constitution currently alluding to electors being selected by popular vote.

On May 8, 1866, during a debate on the Fourteenth Amendment, Thaddeus Stevens, the leader of the Republicans in the House of Representatives, delivered a speech on the amendment's intent. Regarding Section 2, he said:

The second section I consider the most important in the article. It fixes the basis of representation in Congress. If any State shall exclude any of her adult male citizens from the elective franchise, or abridge that right, she shall forfeit her right to representation in the same proportion. The effect of this provision will be either to compel the States to grant universal suffrage or so shear them of their power as to keep them forever in a hopeless minority in the national Government, both legislative and executive.

Federal law (2 U.S.C. § 6) implements Section 2's mandate.

Meeting of electors

Article II, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution authorises Congress to fix the day on which the electors shall vote, which must be the same day throughout the United States. Since 1936, the date fixed by Congress for the meeting of the Electoral College "on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December next following their appointment".

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2, disqualifies all elected and appointed federal officials from being electors. The Office of the Federal Register is charged with administering the Electoral College.

After the vote, each state sends to Congress a certified record of their electoral votes, called the Certificate of Vote. These certificates are opened during a joint session of Congress, held in the first week of January, and read aloud by the incumbent vice president, acting in his capacity as President of the Senate. If any person receives an absolute majority of electoral votes, that person is declared the winner. If there is a tie, or if no candidate for either or both offices receives an absolute majority, then choice falls to Congress in a procedure known as a contingent election.

Modern mechanics

Summary

Even though the aggregate national popular vote is calculated by state officials, media organizations, and the Federal Election Commission, the people only indirectly elect the president. The president and vice president of the United States are elected by the Electoral College, which consists of 538 electors from the fifty states and Washington, D.C. Electors are selected state-by-state, as determined by the laws of each state. Since the election of 1824, the majority of states have chosen their presidential electors based on winner-take-all results in the statewide popular vote on Election Day. As of 2020, Maine and Nebraska are exceptions as both use the congressional district method; Maine since 1972 and in Nebraska since 1996. In most states, the popular vote ballots list the names of the presidential and vice presidential candidates (who run on a ticket). The slate of electors that represent the winning ticket will vote for those two offices. Electors are nominated by a party and pledged to vote for their party's candidate. Many states require an elector to vote for the candidate to which the elector is pledged, and most electors do regardless, but some "faithless electors" have voted for other candidates or refrained from voting.

A candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270) to win the presidency or the vice presidency. If no candidate receives a majority in the election for president or vice president, the election is determined via a contingency procedure established by the Twelfth Amendment. In such a situation, the House chooses one of the top three presidential electoral vote winners as the president, while the Senate chooses one of the top two vice presidential electoral vote winners as vice president.

Electors

Apportionment

Further information: United States congressional apportionment

A state's number of electors equals the number of representatives plus two electors for the senators the state has in the United States Congress. The number of representatives is based on the respective populations, determined every ten years by the United States Census. Based on the 2010 census, each representative represented on average 711,000 individuals.

Under the Twenty-third Amendment, Washington, D.C., is allocated as many electors as it would have if it were a state but no more electors than the least populous state. Because the least populous state (Wyoming, according to the 2010 census) has three electors, D.C. cannot have more than three electors. Even if D.C. were a state, its population would entitle it to only three electors. Based on its population per electoral vote, D.C. has the second highest per capita Electoral College representation, after Wyoming.

Currently, there are 538 electors, based on 435 representatives, 100 senators from the fifty states and three electors from Washington, D.C. The six states with the most electors are California (55), Texas (38), New York (29), Florida (29), Illinois (20), and Pennsylvania (20). The District of Columbia and the seven least populous states — Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming — have three electors each.

Nominations

The custom of allowing recognized political parties to select a slate of prospective electors developed early. In contemporary practice, each presidential-vice presidential ticket has an associated slate of potential electors. Then on Election Day, the voters select a ticket and thereby select the associated electors.

Candidates for elector are nominated by state chapters of nationally oriented political parties in the months prior to Election Day. In some states, the electors are nominated by voters in primaries the same way other presidential candidates are nominated. In some states, such as Oklahoma, Virginia, and North Carolina, electors are nominated in party conventions. In Pennsylvania, the campaign committee of each candidate names their respective electoral college candidates (an attempt to discourage faithless electors). Varying by state, electors may also be elected by state legislatures or appointed by the parties themselves.

Selection process

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution requires each state legislature to determine how electors for the state are to be chosen, but it disqualifies any person holding a federal office, either elected or appointed, from being an elector. Under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, any person who has sworn an oath to support the United States Constitution in order to hold either a state or federal office, and later rebelled against the United States directly or by giving assistance to those doing so, is disqualified from being an elector. However, Congress may remove this disqualification by a two-thirds vote in each House.

All states currently choose presidential electors by popular vote. Except for eight states, the "short ballot" is used. The short ballot displays the names of the candidates for president and vice president, rather than the names of prospective electors. Some states support voting for write-in candidates; those that do may require pre-registration of write-in candidacy, with designation of electors being done at that time. Since 1996, all but two states have followed the winner takes all method of allocating electors by which every person named on the slate for the ticket winning the statewide popular vote are named as presidential electors. Maine and Nebraska are the only states not using this method. In those states, the winner of the popular vote in each of its congressional districts is awarded one elector, and the winner of the statewide vote is then awarded the state's remaining two electors. This method has been used in Maine since 1972 and in Nebraska since 1996. The Supreme Court previously upheld the power for a state to choose electors on the basis of congressional districts, holding that states possess plenary power to decide how electors are appointed in McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U.S. 1 (1892).

The Tuesday following the first Monday in November has been fixed as the day for holding federal elections, called the Election Day. After the election, each state prepares seven Certificates of Ascertainment, each listing the candidates for president and vice president, their pledged electors, and the total votes each candidacy received. One certificate is sent, as soon after Election Day as practicable, to the National Archivist in Washington. The Certificates of Ascertainment are mandated to carry the state seal and the signature of the governor (or mayor of D.C.).

Meetings

| External media | |

|---|---|

| Images | |

| Video | |

The Electoral College never meets as one body. Electors meet in their respective state capitals (electors for the District of Columbia meet within the District) on the Monday after the second Wednesday in December, at which time they cast their electoral votes on separate ballots for president and vice president.

Although procedures in each state vary slightly, the electors generally follow a similar series of steps, and the Congress has constitutional authority to regulate the procedures the states follow. The meeting is opened by the election certification official – often that state's secretary of state or equivalent — who reads the Certificate of Ascertainment. This document sets forth who was chosen to cast the electoral votes. The attendance of the electors is taken and any vacancies are noted in writing. The next step is the selection of a president or chairman of the meeting, sometimes also with a vice chairman. The electors sometimes choose a secretary, often not himself an elector, to take the minutes of the meeting. In many states, political officials give short speeches at this point in the proceedings.

When the time for balloting arrives, the electors choose one or two people to act as tellers. Some states provide for the placing in nomination of a candidate to receive the electoral votes (the candidate for president of the political party of the electors). Each elector submits a written ballot with the name of a candidate for president. Ballot formats vary between the states: in New Jersey for example, the electors cast ballots by checking the name of the candidate on a pre-printed card; in North Carolina, the electors write the name of the candidate on a blank card. The tellers count the ballots and announce the result. The next step is the casting of the vote for vice president, which follows a similar pattern.

Under the Electoral Count Act (updated and codified in 3 U.S.C. § 9), each state's electors must complete six Certificates of Vote. Each Certificate of Vote must be signed by all of the electors and a Certificate of Ascertainment must be attached to each of the Certificates of Vote. Each Certificate of Vote must include the names of those who received an electoral vote for either the office of president or of vice president. The electors certify the Certificates of Vote, and copies of the Certificates are then sent in the following fashion:

- One is sent by registered mail to the President of the Senate (who usually is the incumbent vice president of the United States);

- Two are sent by registered mail to the Archivist of the United States;

- Two are sent to the state's Secretary of State; and

- One is sent to the chief judge of the United States district court where those electors met.

A staff member of the President of the Senate collects the Certificates of Vote as they arrive and prepares them for the joint session of the Congress. The Certificates are arranged – unopened – in alphabetical order and placed in two special mahogany boxes. Alabama through Missouri (including the District of Columbia) are placed in one box and Montana through Wyoming are placed in the other box. Before 1950, the Secretary of State's office oversaw the certifications, but since then the Office of Federal Register in the Archivist's office reviews them to make sure the documents sent to the archive and Congress match and that all formalities have been followed, sometimes requiring states to correct the documents.

Faithlessness

Main article: Faithless electorAn elector votes for each office, but at least one of these votes (president or vice president) must be cast for a person who is not a resident of the same state as that elector. A "faithless elector" is one who does not cast an electoral vote for the candidate of the party for whom that elector pledged to vote. Thirty-three states plus the District of Columbia have laws against faithless electors, which were first enforced after the 2016 election, where ten electors voted or attempted to vote contrary to their pledges. Faithless electors have never changed the outcome of a U.S. election for president. Altogether, 23,529 electors have taken part in the Electoral College as of the 2016 election; only 165 electors have cast votes for someone other than their party's nominee. Of that group, 71 did so because the nominee had died – 63 Democratic Party electors in 1872, when presidential nominee Horace Greeley died; and eight Republican Party electors in 1912, when vice presidential nominee James S. Sherman died.

While faithless electors have never changed the outcome of any presidential election, there are two occasions where the vice presidential election has been influenced by faithless electors:

- In the 1796 election, 18 electors pledged to the Federalist Party ticket cast their first vote as pledged for John Adams, electing him president, but did not cast their second vote for his running mate Thomas Pinckney. As a result, Adams attained 71 electoral votes, Jefferson received 68, and Pinckney received 59, meaning Jefferson, rather than Pinckney, became vice president.

- In the 1836 election, Virginia's 23 electors, who were pledged to Richard Mentor Johnson, voted instead for former U.S. Senator William Smith, which left Johnson one vote short of the majority needed to be elected. In accordance with the Twelfth Amendment, a contingent election was held in the Senate between the top two receivers of electoral votes, Johnson and Francis Granger, for vice president, with Johnson being elected on the first ballot.

Some constitutional scholars argued that state restrictions would be struck down if challenged based on Article II and the Twelfth Amendment. However, the United States Supreme Court has consistently ruled that state restrictions are allowed under the Constitution. In Ray v. Blair, 343 U.S. 214 (1952), the Court ruled in favor of state laws requiring electors to pledge to vote for the winning candidate, as well as removing electors who refuse to pledge. As stated in the ruling, electors are acting as a functionary of the state, not the federal government. In Chiafalo v. Washington, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), and a related case, the Court held that electors must vote in accord with their state's laws. Faithless electors also may face censure from their political party, as they are usually chosen based on their perceived party loyalty.

Joint session of Congress

Main article: Electoral Count Act| External videos | |

|---|---|

The Twelfth Amendment mandates Congress assemble in joint session to count the electoral votes and declare the winners of the election. The session is ordinarily required to take place on January 6 in the calendar year immediately following the meetings of the presidential electors. Since the Twentieth Amendment, the newly elected Congress declares the winner of the election; all elections before 1936 were determined by the outgoing House.

The Office of the Federal Register is charged with administering the Electoral College. The meeting is held at 1 p.m. in the Chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives. The sitting vice president is expected to preside, but in several cases the president pro tempore of the Senate has chaired the proceedings. The vice president and the Speaker of the House sit at the podium, with the vice president in the seat of the Speaker of the House. Senate pages bring in the two mahogany boxes containing each state's certified vote and place them on tables in front of the senators and representatives. Each house appoints two tellers to count the vote (normally one member of each political party). Relevant portions of the certificate of vote are read for each state, in alphabetical order.

Members of Congress can object to any state's vote count, provided objection is presented in writing and is signed by at least one member of each house of Congress. An objection supported by at least one senator and one representative will be followed by the suspension of the joint session and by separate debates and votes in each House of Congress; after both Houses deliberate on the objection, the joint session is resumed.

A state's certificate of vote can be rejected only if both Houses of Congress vote to accept the objection, meaning the votes from the State in question are not counted. Individual votes can also be rejected, and are also not counted.

In 1864, all of the votes from Louisiana and Tennessee were rejected, and in 1872, all of the votes from Arkansas and Louisiana plus three of the eleven electoral votes from Georgia were rejected.

Objections to the electoral vote count are rarely raised, although it did occur during the vote count in 2001 after the close 2000 presidential election between Governor George W. Bush of Texas and the vice president of the United States, Al Gore. Gore, who as vice president was required to preside over his own Electoral College defeat (by five electoral votes), denied the objections, all of which were raised by only several representatives and would have favored his candidacy, after no senators would agree to jointly object. Objections were again raised in the vote count of the 2004 elections, and on that occasion the document was presented by one representative and one senator. Although the joint session was suspended, the objections were quickly disposed of and rejected by both Houses of Congress.

If there are no objections or all objections are overruled, the presiding officer simply includes a state's votes, as declared in the certificate of vote, in the official tally.

After the certificates from all states are read and the respective votes are counted, the presiding officer simply announces the final state of the vote. This announcement concludes the joint session and formalizes the recognition of the president-elect and of the vice president-elect. The senators then depart from the House Chamber. The final tally is printed in the Senate and House journals.

Contingencies

Further information: Contingent electionContingent presidential election by House

The Twelfth Amendment requires the House of Representatives to go into session immediately to vote for a president if no candidate for president receives a majority of the electoral votes (since 1964, 270 of the 538 electoral votes).

In this event, the House of Representatives is limited to choosing from among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes for president. Each state delegation votes en bloc — each delegation having a single vote; the District of Columbia does not get to vote. A candidate must receive an absolute majority of state delegation votes (i.e., at present, a minimum of 26 votes) in order for that candidate to become the president-elect. Additionally, delegations from at least two thirds of all the states must be present for voting to take place. The House continues balloting until it elects a president.

The House of Representatives has chosen the president only twice: in 1801 under Article II, Section 1, Clause 3; and in 1825 under the Twelfth Amendment.

Contingent vice presidential election by Senate

If no candidate for vice president receives an absolute majority of electoral votes, then the Senate must go into session to elect a vice president. The Senate is limited to choosing from the two candidates who received the most electoral votes for vice president. Normally this would mean two candidates, one less than the number of candidates available in the House vote. However, the text is written in such a way that all candidates with the most and second most electoral votes are eligible for the Senate election – this number could theoretically be larger than two. The Senate votes in the normal manner in this case (i.e., ballots are individually cast by each senator, not by state delegations). However, two-thirds of the senators must be present for voting to take place.

Additionally, the Twelfth Amendment states a "majority of the whole number" of senators (currently 51 of 100) is necessary for election. Further, the language requiring an absolute majority of Senate votes precludes the sitting vice president from breaking any tie that might occur, although some academics and journalists have speculated to the contrary.

The only time the Senate chose the vice president was in 1837. In that instance, the Senate adopted an alphabetical roll call and voting aloud. The rules further stated, "f a majority of the number of senators shall vote for either the said Richard M. Johnson or Francis Granger, he shall be declared by the presiding officer of the Senate constitutionally elected Vice President of the United States"; the Senate chose Johnson.

Deadlocked election

Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment specifies if the House of Representatives has not chosen a president-elect in time for the inauguration (noon EST on January 20), then the vice president-elect becomes acting president until the House selects a president. Section 3 also specifies Congress may statutorily provide for who will be acting president if there is neither a president-elect nor a vice president-elect in time for the inauguration. Under the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, the Speaker of the House would become acting president until either the House selects a president or the Senate selects a vice president. Neither of these situations has ever occurred.

Current electoral vote distribution

| EV × States | States |

|---|---|

| 55 × 1 = 55 | California |

| 38 × 1 = 38 | Texas |

| 29 × 2 = 58 | Florida, New York |

| 20 × 2 = 40 | Illinois, Pennsylvania |

| 18 × 1 = 18 | Ohio |

| 16 × 2 = 32 | Georgia, Michigan |

| 15 × 1 = 15 | North Carolina |

| 14 × 1 = 14 | New Jersey |

| 13 × 1 = 13 | Virginia |

| 12 × 1 = 12 | Washington |

| 11 × 4 = 44 | Arizona, Indiana, Massachusetts, Tennessee |

| 10 × 4 = 40 | Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Wisconsin |

| 9 × 3 = 27 | Alabama, Colorado, South Carolina |

| 8 × 2 = 16 | Kentucky, Louisiana |

| 7 × 3 = 21 | Connecticut, Oklahoma, Oregon |

| 6 × 6 = 36 | Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Mississippi, Nevada, Utah |

| 5 × 3 = 15 | Nebraska**, New Mexico, West Virginia |

| 4 × 5 = 20 | Hawaii, Idaho, Maine**, New Hampshire, Rhode Island |

| 3 × 8 = 24 | Alaska, Delaware, District of Columbia*, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, Wyoming |

| = 538 | Total electors |

- * The Twenty-third Amendment grants DC the same number of electors as the least populous state. This has always been three.

- ** Maine's four electors and Nebraska's five are distributed using the Congressional district method.

Chronological table

See also: Electoral vote changes between United States presidential elections| Election year |

1788–1800 | 1804–1900 | 1904–2000 | 2004– | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| '88 | '92 | '96 '00 |

'04 '08 |

'12 | '16 | '20 | '24 '28 |

'32 | '36 '40 |

'44 | '48 | '52 '56 |

'60 | '64 | '68 | '72 | '76 '80 |

'84 '88 |

'92 | '96 '00 |

'04 | '08 | '12 '16 '20 '24 '28 |

'32 '36 '40 |

'44 '48 |

'52 '56 |

'60 | '64 '68 |

'72 '76 '80 |

'84 '88 |

'92 '96 '00 |

'04 '08 |

'12 '16 '20 | ||

| # | Total | 81 | 135 | 138 | 176 | 218 | 221 | 235 | 261 | 288 | 294 | 275 | 290 | 296 | 303 | 234 | 294 | 366 | 369 | 401 | 444 | 447 | 476 | 483 | 531 | 537 | 538 | ||||||||

| State | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | Alabama | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | ||||||

| 49 | Alaska | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48 | Arizona | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | Arkansas | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||||||

| 31 | California | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 22 | 25 | 32 | 32 | 40 | 45 | 47 | 54 | 55 | 55 | ||||||||||||

| 38 | Colorado | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Connecticut | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| – | D.C. | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Delaware | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 27 | Florida | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 17 | 21 | 25 | 27 | 29 | |||||||||||

| 4 | Georgia | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 16 |

| 50 | Hawaii | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43 | Idaho | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | Illinois | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 16 | 16 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 27 | 27 | 29 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 20 | ||||||

| 19 | Indiana | 3 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | |||||

| 29 | Iowa | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | |||||||||||

| 34 | Kansas | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| 15 | Kentucky | 4 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 18 | Louisiana | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | ||||

| 23 | Maine | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| 7 | Maryland | 8 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 6 | Massachusetts | 10 | 16 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 22 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 26 | Michigan | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 16 | |||||||||

| 32 | Minnesota | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 20 | Mississippi | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| 24 | Missouri | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | ||||||

| 41 | Montana | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 37 | Nebraska | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||||||||

| 36 | Nevada | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | New Hampshire | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | New Jersey | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 14 |

| 47 | New Mexico | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | New York | 8 | 12 | 12 | 19 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 36 | 42 | 42 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 33 | 33 | 35 | 35 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 39 | 39 | 45 | 47 | 47 | 45 | 45 | 43 | 41 | 36 | 33 | 31 | 29 |

| 12 | North Carolina | 12 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 15 | |

| 39 | North Dakota | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Ohio | 3 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 23 | 21 | 20 | 18 | |||

| 46 | Oklahoma | 7 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | Oregon | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | Pennsylvania | 10 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 28 | 30 | 30 | 26 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 36 | 35 | 32 | 32 | 29 | 27 | 25 | 23 | 21 | 20 |

| 13 | Rhode Island | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 8 | South Carolina | 7 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| 40 | South Dakota | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | Tennessee | 3 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | ||

| 28 | Texas | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 29 | 32 | 34 | 38 | |||||||||||

| 45 | Utah | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Vermont | 4 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 10 | Virginia | 12 | 21 | 21 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| 42 | Washington | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 35 | West Virginia | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| 30 | Wisconsin | 4 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||||

| 44 | Wyoming | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| # | Total | 81 | 135 | 138 | 176 | 218 | 221 | 235 | 261 | 288 | 294 | 275 | 290 | 296 | 303 | 234 | 294 | 366 | 369 | 401 | 444 | 447 | 476 | 483 | 531 | 537 | 538 | ||||||||

Source: Presidential Elections 1789–2000 at Psephos (Adam Carr's Election Archive)

Note: In 1788, 1792, 1796, and 1800, each elector cast two votes for president.

Alternative methods of choosing electors

| Year | AL | CT | DE | GA | IL | IN | KY | LA | ME | MD | MA | MS | MO | NH | NJ | NY | NC | OH | PA | RI | SC | TN | VT | VA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1789 | – | L | D | L | – | – | – | – | – | A | H | – | – | H | L | – | – | – | A | – | L | – | – | D | |||||

| 1792 | – | L | L | L | – | – | D | – | – | A | H | – | – | H | L | L | L | – | A | L | L | – | L | D | |||||

| 1796 | – | L | L | A | – | – | D | – | – | D | H | – | – | H | L | L | D | – | A | L | L | H | L | D | |||||

| 1800 | – | L | L | L | – | – | D | – | – | D | L | – | – | L | L | L | D | – | L | A | L | H | L | A | |||||

| 1804 | – | L | L | L | – | – | D | – | – | D | D | – | – | A | A | L | D | A | A | A | L | D | L | A | |||||

| 1808 | – | L | L | L | – | – | D | – | – | D | L | – | – | A | A | L | D | A | A | A | L | D | L | A | |||||

| 1812 | – | L | L | L | – | – | D | L | – | D | D | – | – | A | L | L | L | A | A | A | L | D | L | A | |||||

| 1816 | – | L | L | L | – | L | D | L | – | D | L | – | – | A | A | L | A | A | A | A | L | D | L | A | |||||

| 1820 | L | A | L | L | D | L | D | L | D | D | D | A | L | A | A | L | A | A | A | A | L | D | L | A | |||||

| 1824 | A | A | L | L | D | A | D | L | D | D | A | A | D | A | A | L | A | A | A | A | L | D | L | A | |||||

| 1828 | A | A | L | A | A | A | A | A | D | D | A | A | A | A | A | D | A | A | A | A | L | D | A | A | |||||

| 1832 | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | D | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | L | A | A | A | |||||

| Year | AL | CT | DE | GA | IL | IN | KY | LA | ME | MD | MA | MS | MO | NH | NJ | NY | NC | OH | PA | RI | SC | TN | VT | VA |

| Key | A | Popular vote, At-large | D | Popular vote, Districting | L | Legislative selection | H | Hybrid system |

|---|

Before the advent of the short ballot in the early 20th century, as described above, the most common means of electing the presidential electors was through the general ticket. The general ticket is quite similar to the current system and is often confused with it. In the general ticket, voters cast ballots for individuals running for presidential elector (while in the short ballot, voters cast ballots for an entire slate of electors). In the general ticket, the state canvass would report the number of votes cast for each candidate for elector, a complicated process in states like New York with multiple positions to fill. Both the general ticket and the short ballot are often considered at-large or winner-takes-all voting. The short ballot was adopted by the various states at different times; it was adopted for use by North Carolina and Ohio in 1932. Alabama was still using the general ticket as late as 1960 and was one of the last states to switch to the short ballot.

The question of the extent to which state constitutions may constrain the legislature's choice of a method of choosing electors has been touched on in two U.S. Supreme Court cases. In McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U.S. 1 (1892), the Court cited Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 which states that a state's electors are selected "in such manner as the legislature thereof may direct" and wrote these words "operat as a limitation upon the state in respect of any attempt to circumscribe the legislative power". In Bush v. Palm Beach County Canvassing Board, 531 U.S. 70 (2000), a Florida Supreme Court decision was vacated (not reversed) based on McPherson. On the other hand, three dissenting justices in Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000), wrote: "othing in Article II of the Federal Constitution frees the state legislature from the constraints in the State Constitution that created it." Extensive research on alternate methods of electoral allocation have been conducted by Collin Welke, Dylan Shearer, and Riley Wagie in 2019.

Appointment by state legislature

In the earliest presidential elections, state legislative choice was the most common method of choosing electors. A majority of the state legislatures selected presidential electors in both 1792 (9 of 15) and 1800 (10 of 16), and half of them did so in 1812. Even in the 1824 election, a quarter of state legislatures (6 of 24) chose electors. (In that election, Andrew Jackson lost in spite of having plurality of the popular vote and the number of electoral votes representing them, but six state legislatures chose electors that overturned that result.) Some state legislatures simply chose electors, while other states used a hybrid method in which state legislatures chose from a group of electors elected by popular vote. By 1828, with the rise of Jacksonian democracy, only Delaware and South Carolina used legislative choice. Delaware ended its practice the following election (1832), while South Carolina continued using the method until it seceded from the Union in December 1860. South Carolina used the popular vote for the first time in the 1868 election.

Excluding South Carolina, legislative appointment was used in only four situations after 1832:

- In 1848, Massachusetts statute awarded the state's electoral votes to the winner of the at-large popular vote, but only if that candidate won an absolute majority. When the vote produced no winner between the Democratic, Free Soil, and Whig parties, the state legislature selected the electors, giving all 12 electoral votes to the Whigs.

- In 1864, Nevada, having joined the Union only a few days prior to Election Day, had no choice but to legislatively appoint.

- In 1868, the newly reconstructed state of Florida legislatively appointed its electors, having been readmitted too late to hold elections.

- Finally, in 1876, the legislature of the newly admitted state of Colorado used legislative choice due to a lack of time and money to hold a popular election.

Legislative appointment was brandished as a possibility in the 2000 election. Had the recount continued, the Florida legislature was prepared to appoint the Republican slate of electors to avoid missing the federal safe-harbor deadline for choosing electors.

The Constitution gives each state legislature the power to decide how its state's electors are chosen and it can be easier and cheaper for a state legislature to simply appoint a slate of electors than to create a legislative framework for holding elections to determine the electors. As noted above, the two situations in which legislative choice has been used since the Civil War have both been because there was not enough time or money to prepare for an election. However, appointment by state legislature can have negative consequences: bicameral legislatures can deadlock more easily than the electorate. This is precisely what happened to New York in 1789 when the legislature failed to appoint any electors.

Electoral districts

Another method used early in U.S. history was to divide the state into electoral districts. By this method, voters in each district would cast their ballots for the electors they supported and the winner in each district would become the elector. This was similar to how states are currently separated into congressional districts. However, the difference stems from the fact that every state always had two more electoral districts than congressional districts. As with congressional districts, moreover, this method is vulnerable to gerrymandering.

Congressional district method

There are two versions of the congressional district method: one has been implemented in Maine and Nebraska; another, in Virginia, has only been proposed. Under the implemented means, one electoral vote goes per the plurality of the popular votes of each congressional district (for the U.S. House of Representatives); and two per the statewide popular vote. This may result in greater proportionality. It has often acted as the other states, as in 1992, when George H. W. Bush won all five of Nebraska's electoral votes with a clear plurality on 47% of the vote; in a truly proportional system, he would have received three and Bill Clinton and Ross Perot each would have received one.

In 2013, the Virginia proposal was tabled. Like the other congressional district methods, this would have distributed the electoral votes based on the popular vote winner within each of Virginia's 11 congressional districts; but unlike those, the two statewide electoral votes would be awarded based on which candidate won the most congressional districts.

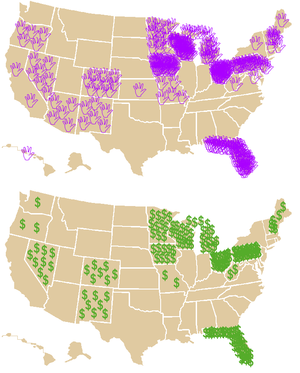

A congressional district method is more likely to arise than other alternatives to the winner-takes-whole-state method, in view of the main two parties resistance to scrap first-past-the-post. State legislation is sufficient to use this method. Advocates of the method believe the system encourages higher voter turnout and/or incentivizes candidates, often, to visit and appeal to states deemed "safe", overall, for one party. Winner-take-all systems ignore thousands of popular votes; in Democratic California there are Republican districts, in Republican Texas there are Democratic districts. Because candidates have an incentive to campaign in competitive districts, with a district plan, candidates have an incentive to actively campaign in over thirty states versus about seven "swing" states. Opponents of the system, however, argue candidates might only spend time in certain battleground districts instead of the entire state and cases of gerrymandering could become exacerbated as political parties attempt to draw as many safe districts as they can.

Unlike simple congressional district comparisons, the district plan popular vote bonus in the 2008 election would have given Obama 56% of the Electoral College versus the 68% he did win; it "would have more closely approximated the percentage of the popular vote won ".

Implementation

Of the 43 multi-district states whose 514 electoral votes are amenable to the method, Maine (4 EV) and Nebraska (5 EV) use it. Maine began using the congressional district method in the election of 1972. Nebraska has used the congressional district method since the election of 1992. Michigan used the system for the 1892 presidential election, and several other states used various forms of the district plan before 1840: Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Illinois, Maine, Missouri, and New York.

The congressional district method allows a state the chance to split its electoral votes between multiple candidates. Prior to 2008, neither Maine nor Nebraska had ever split their electoral votes. Nebraska split its electoral votes for the first time in 2008, giving John McCain its statewide electors and those of two congressional districts, while Barack Obama won the electoral vote of Nebraska's 2nd congressional district. Following the 2008 split, some Nebraska Republicans made efforts to discard the congressional district method and return to the winner-takes-all system. In January 2010, a bill was introduced in the Nebraska legislature to revert to a winner-take-all system; the bill died in committee in March 2011. Republicans had passed bills in 1995 and 1997 to do the same, vetoed by Democratic Governor Ben Nelson.

- Recent abandoned adoption in other states

In 2010, Republicans in Pennsylvania, who controlled both houses of the legislature as well as the governorship, put forward a plan to change the state's winner-takes-all system to a congressional district method system. Pennsylvania had voted for the Democratic candidate in the five previous presidential elections, so some saw this as an attempt to take away Democratic electoral votes. Although Democrat Barack Obama won Pennsylvania in 2008, he won 55% of its popular vote. The district plan would have awarded him 11 of its 21 electoral votes, a 52.4% which was much closer to the popular vote percentage. The plan later lost support. Other Republicans, including Michigan state representative Pete Lund, RNC Chairman Reince Priebus, and Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, have floated similar ideas.

Proportional vote

In a proportional system, electors would be selected in proportion to the votes cast for their candidate or party, rather than being selected by the statewide plurality vote.

Contemporary issues

Arguments between proponents and opponents of the current electoral system include four separate but related topics: indirect election, disproportionate voting power by some states, the winner-takes-all distribution method (as chosen by 48 of the 50 states), and federalism. Arguments against the Electoral College in common discussion focus mostly on the allocation of the voting power among the states. Gary Bugh's research of congressional debates over proposed constitutional amendments to abolish the Electoral College reveals reform opponents have often appealed to a traditional republican version of representation, whereas reform advocates have tended to reference a more democratic view.

Criticism

Nondeterminacy of popular vote

See also: List of United States presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote

The elections of 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016 produced an Electoral College winner who did not receive at least a plurality of the nationwide popular vote. In 1824, there were six states in which electors were legislatively appointed, rather than popularly elected, so it is uncertain what the national popular vote would have been if all presidential electors had been popularly elected. When no candidate received a majority of electoral votes in 1824, the election was decided by the House of Representatives and so could be considered distinct from the latter four elections in which all of the states had popular selection of electors. The true national popular vote was also uncertain in the 1960 election, and the plurality for the winner depends on how votes for Alabama electors are allocated.

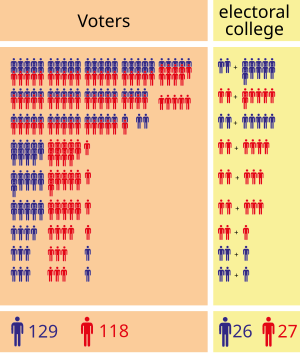

Opponents of the Electoral College claim such outcomes do not logically follow the normative concept of how a democratic system should function. One view is the Electoral College violates the principle of political equality, since presidential elections are not decided by the one-person one-vote principle. Outcomes of this sort are attributable to the federal nature of the system. Supporters of the Electoral College argue candidates must build a popular base that is geographically broader and more diverse in voter interests than either a simple national plurality or majority. Neither is this feature attributable to having intermediate elections of presidents, caused instead by the winner-takes-all method of allocating each state's slate of electors. Allocation of electors in proportion to the state's popular vote could reduce this effect.

Proponents of a national popular vote point out that the combined population of the 50 biggest cities (not including metropolitan areas) amounts to only 15% of the population. They also assert that candidates in popular vote elections for governor and U.S. Senate, and for statewide allocation of electoral votes, do not ignore voters in less populated areas. In addition, it is already possible to win the required 270 electoral votes by winning only the 11 most populous states; what currently prevents such a result is the organic political diversity between those states (three reliably Republican states, four swing states, and four reliably Democratic states), not any inherent quality of the Electoral College itself.